Can you still buy gold?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Can you still buy gold?

Gold today is less a tool for making money and more like an insurance policy that loses money.

Author | Ding Ping

Can gold, which has "soared to the skies," still be part of your portfolio?

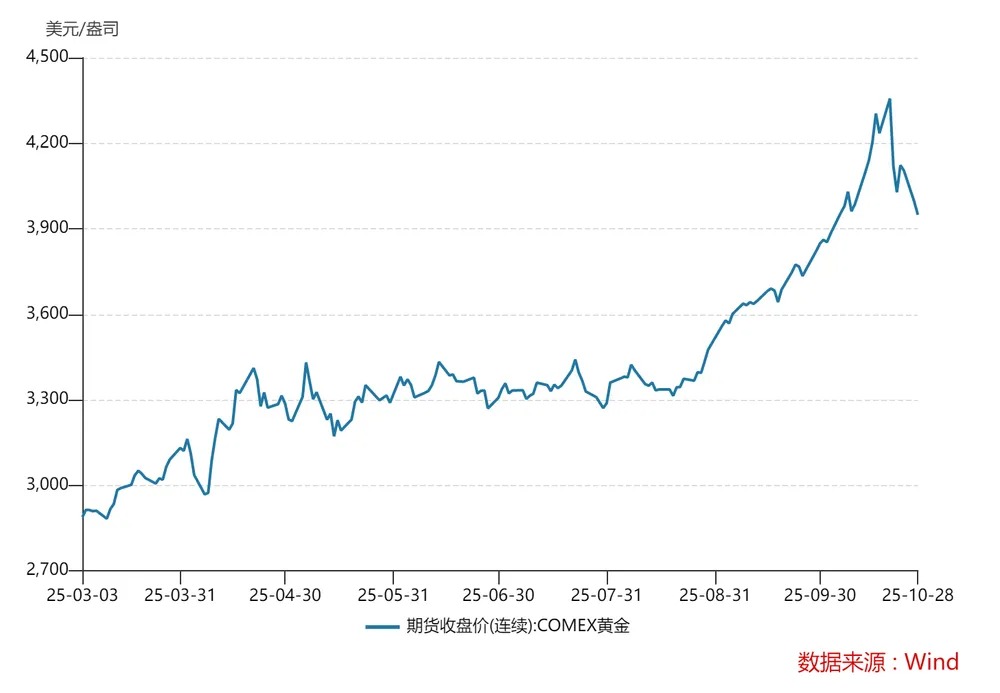

Gold prices have surged aggressively this year, skyrocketing from $3,000/oz to $4,000/oz in just seven months. On October 20, COMEX gold hit a record high of $4,398/oz, only to plunge 5.07% the following evening—the largest single-day drop since its listing. The downtrend continued, falling below the $4,000/oz mark by October 29, retreating nearly 10% over eight trading sessions.

Bearish sentiment in the market is growing. According to CME Delta exposure data, about 52,000 lots of put option selling positions are concentrated in the $4,000–$3,900 range.

There are also rumors that Philippine banks intend to sell gold. Benjamin Diokno, a member of the Monetary Board of the Central Bank of the Philippines and former central bank governor, recently stated that their gold holdings account for about 13%, higher than most Asian central banks. Diokno believes the ideal gold reserve ratio should be maintained between 8% and 12%.

This statement has been interpreted by the market as a potential signal of减持 (reduction), further intensifying bearish sentiment—has gold truly peaked?

Here's the conclusion: Gold has not yet peaked, but its explosive growth phase is over. Today’s gold is less a tool for making money and more like costly insurance.

Gold Is the Shadow of the Energy Order

In the modern fiat currency system, the U.S. dollar’s role as the global settlement currency relies not only on strong military and financial networks but also on its control over energy pricing. As long as global energy trade requires dollar settlements, petrodollars remain the core of this system.

In 1974, the United States signed a key agreement with Saudi Arabia and other major oil-producing countries: all global oil transactions must be settled in dollars. In exchange, the U.S. promised military protection and economic support. From then on, oil became the “new anchor” of the fiat currency era. As long as energy prices remain stable, the credibility of the dollar remains intact.

When energy costs are manageable and production efficiency continues to rise, inflation struggles to take off, creating “favorable conditions” for the expansion of the dollar system.

In simple terms, if economic growth is high and inflation low, returns on dollar assets can offset the pace of monetary easing, causing gold to naturally fall into obscurity.

This explains a phenomenon: at times, gold’s gains lag far behind the pace of dollar printing. Since 2008, the Federal Reserve's balance sheet has expanded nearly ninefold (as of end-2023), while gold prices have risen only about 4.6 times over the same period.

Conversely, when energy ceases to be a shared efficiency dividend and instead becomes a weaponized strategic resource, the physical foundation supporting dollar expansion through stable, low-cost energy begins to unravel. When dollar credibility can no longer be sustained by cheap goods, gold—as an asset with zero credit risk—naturally attracts capital inflows.

This is why gold almost always enters a bull market whenever there is turmoil in the energy order or a repricing of energy costs.

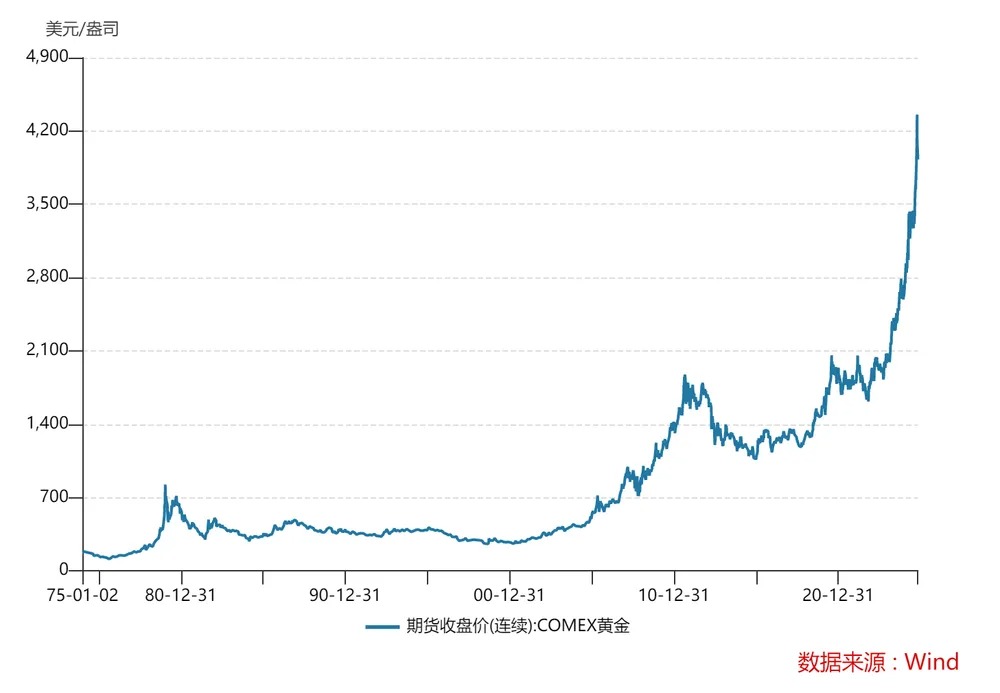

The largest historical surge in gold prices occurred between 1971 and 1980. During this decade, gold rose from $35/oz to $850/oz—an increase of approximately 24 times. Three major events took place during this period:

In 1971, the Bretton Woods system collapsed, severing the dollar’s link to gold, ending the fixed price of $35/oz;

In 1973, the first oil crisis erupted. After the Middle East War, OPEC coordinated production cuts, sending oil prices from $3/barrel to $12;

In 1979, the Iranian Revolution triggered the second oil crisis, pushing oil prices up to $40.

Similarly, the second-largest rise in gold prices also coincided with energy imbalance.

From 2001 to 2011, gold climbed from $255/oz to $1,921/oz, a gain of 650%.

After the bursting of the "dot-com bubble" in 2000, the U.S. economy fell into recession in 2001. The Fed responded with aggressive rate cuts starting January 2001, reducing the federal funds rate from 6.5% to 1% by June 2003. Over the same period, the dollar index dropped from 120 to around 85—a decline of about 25%, the largest depreciation since the adoption of floating exchange rates in 1973.

Dollar depreciation directly eroded the reserve value for oil exporters, forcing them to reduce reliance on the dollar and shift toward other currencies such as the euro and renminbi. In 2000, Iraq’s central bank announced that from November 2001, its oil exports would be priced in euros (“petroeuro”). In 2003, Iran publicly studied an “Iran Crude Oil Exchange” denominated in euros, and later formally invoiced European and Asian customers in euros between 2006 and 2008.

This de-dollarization trend directly threatened U.S. energy-financial interests. The U.S. launched the Iraq War in 2003, increasing global crude supply risks; from 2004 to 2008, energy demand surged in emerging economies like China and India. Oil prices consequently rose from $25/barrel to $147/barrel (mid-2008). Uncontrolled energy costs led to imported inflation, weakening dollar purchasing power and driving a massive gold rally.

The most recent episode occurred between 2020 and 2022. The pandemic disrupted supply chains, prompting the Fed to cut rates twice for a total of 150 basis points, returning to 0–0.25%, and launching unlimited QE (quantitative easing). The Russia-Ukraine conflict triggered a European energy crisis, sending TTF natural gas futures soaring and Brent crude briefly approaching $139/barrel. Gold once again became a safe haven against systemic risk, rising from $1,500/oz to $2,070/oz.

Thus, gold’s rise is not merely due to monetary expansion, but also a result of rebalancing between energy and the dollar system.

Markets Shift from Order to Disorder

As mentioned above, for decades, globalization and technological progress continuously created “negative entropy”—new capacity, greater efficiency, and wealth accumulation. People preferred investing in enterprises and markets rather than non-interest-bearing gold.

However, once cracks appear in this “negative entropy” supply chain—such as uncontrollable energy prices, industrial relocation, or technological decoupling—the gains in new capacity and efficiency disappear, and the system shifts from “negative entropy” to “entropy increase.”

(TechFlow note: In physics, “entropy” represents disorder; in economics and monetary systems, it corresponds to declining efficiency, resource waste, and dissipation of credit. “Negative entropy” means system ordering, improved productivity, and smooth energy cycles; “entropy increase” implies rising prices, uncontrolled expectations, and movement from order to chaos—a world that becomes “lively but inefficient.”)

As long as this entropy-increasing process continues—that is, as market inefficiency leads to runaway inflation—gold’s upward momentum will be supported. Currently, market disorder persists.

The most direct manifestation is rising fiscal deficits and monetary expansion, gradually eroding national credit.

Post-pandemic, governments worldwide are trapped in a cycle of “spending more while becoming poorer,” with government spending unable to contract and debt rollover becoming routine. The U.S. fiscal deficit has consistently exceeded 6% of GDP, with annual net bond issuance expected to surpass $2.2 trillion. Although the Fed has undergone balance sheet contraction, its balance sheet remains in the trillions of dollars.

Other major economies also face unprecedented fiscal pressures in 2025—Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio stands at 250%; the eurozone’s overall fiscal deficit is 3.4%, exceeding limits for four consecutive years, with France, Italy, and Spain at 5.5%, 4.8%, and 3.9% respectively—all above the 3% threshold.

This explains a seemingly contradictory phenomenon: under loose monetary policy, global 30-year bond yields continue to rise, primarily due to market concerns about future high inflation and governments’ inability to control fiscal deficits, leading investors to demand higher compensation for long-term risks.

In fact, this high-debt state is difficult to reverse. Amid a new round of global tech competition, countries are increasing fiscal spending to sustain strategic investments. Especially between China and the U.S., AI has become the most critical battleground.

China’s recent “Document No. 15” clearly states that scientific innovation, emerging industries, and new quality productive forces are key breakthroughs for achieving “overtaking on a curve.” This means technology and advanced manufacturing are no longer mere industrial issues, but core components of national strategic competitiveness.

The U.S. also has its own policy agenda. On July 23, 2025, the U.S. government released *Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan*, positioning AI at the intersection of technology, industry, and national security, and explicitly calling for accelerated development of data centers, chip manufacturing, and infrastructure.

Therefore, both China and the U.S. will inevitably mobilize national resources to develop AI, meaning fiscal spending cannot shrink—and government debt will keep rising.

Besides, resource and supply chain restructuring are also raising costs.

For decades, the global economy relied on efficient international division of labor and stable energy supplies—production in East Asia, consumption in Europe and America, and settlement mainly within the dollar system. Now, this model is being disrupted by geopolitical tensions, supply chain decoupling, and carbon neutrality policies, making resource flows increasingly inefficient. The cross-border transportation cost of a chip, a ton of copper, or a barrel of oil is rising.

As geopolitical conflicts become the norm, countries are boosting defense spending and stockpiling energy, food, and rare metals. The U.S. military budget hits new highs, Europe restarts its defense industry, and Japan advances its “Defense Capability Enhancement Plan.”

When military spending and strategic reserves crowd out fiscal space, governments tend to resort to monetary financing, resulting in lower real interest rates. This reduces the opportunity cost of holding gold (a non-yielding asset) and increases its relative return.

When monetary expansion no longer creates wealth and energy flows are politicized, gold returns to the center of the monetary system—as the only physical asset accepted universally during war and credit crises, requiring no credit backing or dependence on any specific resource.

The Logic of Gold Allocation Has Changed

Clearly, the long-term bullish case for gold is solid, but you shouldn’t allocate to gold using old logic.

In the past, gold was seen more as an investment vehicle. But today, gold serves one primary purpose: a hedge, especially against equity market risks.

Take gold ETFs, for example. Their annualized returns from 2022 to 2025 were 9.42%, 16.61%, 27.54%, and 47.66%—increasingly attractive. The drivers behind this performance can be summarized in three points:

First, central banks have begun accumulating gold reserves. Data from the World Gold Council shows that since 2022, central bank gold-buying behavior has fundamentally changed. Annual purchases jumped from a historical average of 400–500 tons to over 1,000 tons in 2022, remaining elevated for several years. In 2024, global central banks net-purchased 1,136 tons of gold, the second-highest level on record.

This signifies a shift: central banks are no longer passive participants but key players influencing pricing, altering gold’s traditional valuation logic—such as weakening the negative correlation between gold prices and real U.S. Treasury yields.

Second, frequent geopolitical conflicts. Events like the Russia-Ukraine war and Middle East tensions have not only boosted immediate safe-haven demand but also reinforced central banks’ long-term motivation to buy gold. As a “stateless asset,” gold inherently offers advantages in safety and liquidity, attracting capital in high-risk environments.

Third, a policy pivot by the Federal Reserve. In July 2024, the Fed ended its two-year rate hike cycle and began cutting rates in September. Rate cuts benefit gold in two ways: they reduce the opportunity cost of holding non-yielding gold, and typically coincide with a weaker dollar, benefiting dollar-denominated gold.

The long-term fundamentals for gold remain strong—central banks continue buying, global structural risks persist, and the dollar’s credit cycle is still adjusting. However, in the short term, the forces that drove sharp price increases are weakening. Future gold price gains are likely to be milder and more rational.

While these factors still exist, their marginal impact is diminishing.

The trend of central bank gold purchases is expected to continue (95% of surveyed central banks plan to add more in the next 12 months), but the pace may become more flexible given current record-high prices. Geopolitical uncertainty has become the new normal, providing ongoing safe-haven support, though market sensitivity to individual events may decline due to desensitization. Meanwhile, the Fed’s monetary easing has already been priced in, so the strength of the rate-cut boost may not match the excitement seen before and during the initial phase of the easing cycle.

From an allocation perspective, the probability of gold delivering returns comparable to those from 2022 to 2025 is quite low. While gold prices are far from peaking—Goldman Sachs has even raised its 2026 forecast to $4,900/oz—the future price trajectory won’t be as steep as before. Especially now, with ample liquidity and high market risk appetite, risk assets (stocks, commodities, cryptocurrencies, futures, options, etc.) offer greater opportunities for high returns.

It’s important to remember that risk assets rise quickly but also fall sharply. The biggest current risk for equities stems from macro uncertainties—such as escalating U.S.-China trade tensions, worsening geopolitical conflicts, or a U.S. economic downturn. Once these gray rhinos arrive, risk assets will inevitably face significant corrections, prompting capital to flee to safe havens—with gold being the most representative.

Conversely, when these risks improve marginally, gold pulls back while risk assets rebound. For instance, the recent sharp drop in gold prices was primarily triggered by a sudden cooling of safe-haven sentiment. Thus, gold can form a perfect hedging relationship with risk assets—especially equities.

Overall, gold has not yet peaked, but its explosive phase is over. Within a portfolio, gold’s role should shift from a “high-return asset” to a “hedging tool.”

When stocks are volatile, gold is your safety rope.

But how should ordinary people allocate to gold? The most common methods are physical gold bars, gold ETFs, and accumulated gold accounts—each with pros and cons. However, with the introduction of new gold tax policies, the advantages of gold ETFs have become evident.

On November 1, the Ministry of Finance and the State Taxation Administration issued the *Announcement on Tax Policies Related to Gold*, clarifying new tax rules for gold transactions effective from November 1, 2025, to December 31, 2027.

If you buy physical gold through non-exchange channels (outside the Shanghai Gold Exchange), costs will be significantly higher, as such transactions fall under VAT taxation, incurring a 13% VAT burden that sellers are likely to pass on to consumers. In contrast, ETFs are classified as “financial products” and remain exempt from VAT. Combined with high liquidity and transparent costs, their cost advantage is further amplified.

In terms of investment strategy, we recommend focusing on buying dips rather than chasing rallies.

More importantly, always remember: In an unpredictable market, gold is not a tool for making money, but a tool for protecting wealth.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News