Experiencing the October 11 crypto black swan and CS2 skins market crash firsthand, I discovered the middleman's death trap

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Experiencing the October 11 crypto black swan and CS2 skins market crash firsthand, I discovered the middleman's death trap

You think you're profiting from price differences, but in reality, you're paying for systemic risks.

By San, TechFlow

Among all financial roles, intermediaries are generally considered the most stable and lowest-risk players. In most cases, they don't need to predict market direction—simply providing liquidity allows them to earn substantial profits, seemingly occupying the safest "rent-collecting" position in the market.

However, when a black swan event strikes, these intermediaries are also vulnerable to being crushed by more powerful forces. Ironically, the most professional, well-capitalized, and rigorously risk-managed institutions often suffer heavier losses than retail investors during extreme events—not because they're unprofessional, but because their business model inherently requires them to bear the cost of systemic risks.

As someone actively trading in the crypto space while also following the CS2 skin market—and having personally experienced both recent black swan events—I want to discuss the patterns I've observed across these two virtual asset markets and the lessons they reveal.

Two Black Swans, the Same Victims

On October 11, when I opened my exchange account in the morning, I initially thought it was a system bug underreporting my holdings in some altcoins. Only after repeatedly refreshing and seeing no change did I realize something was wrong. Opening Twitter, I discovered the market had already "exploded."

In this black swan event, although retail investors suffered heavy losses, even greater losses likely occurred among the crypto space's "intermediaries."

The losses intermediaries face during extreme market conditions are not accidental—they are an inevitable manifestation of structural risk.

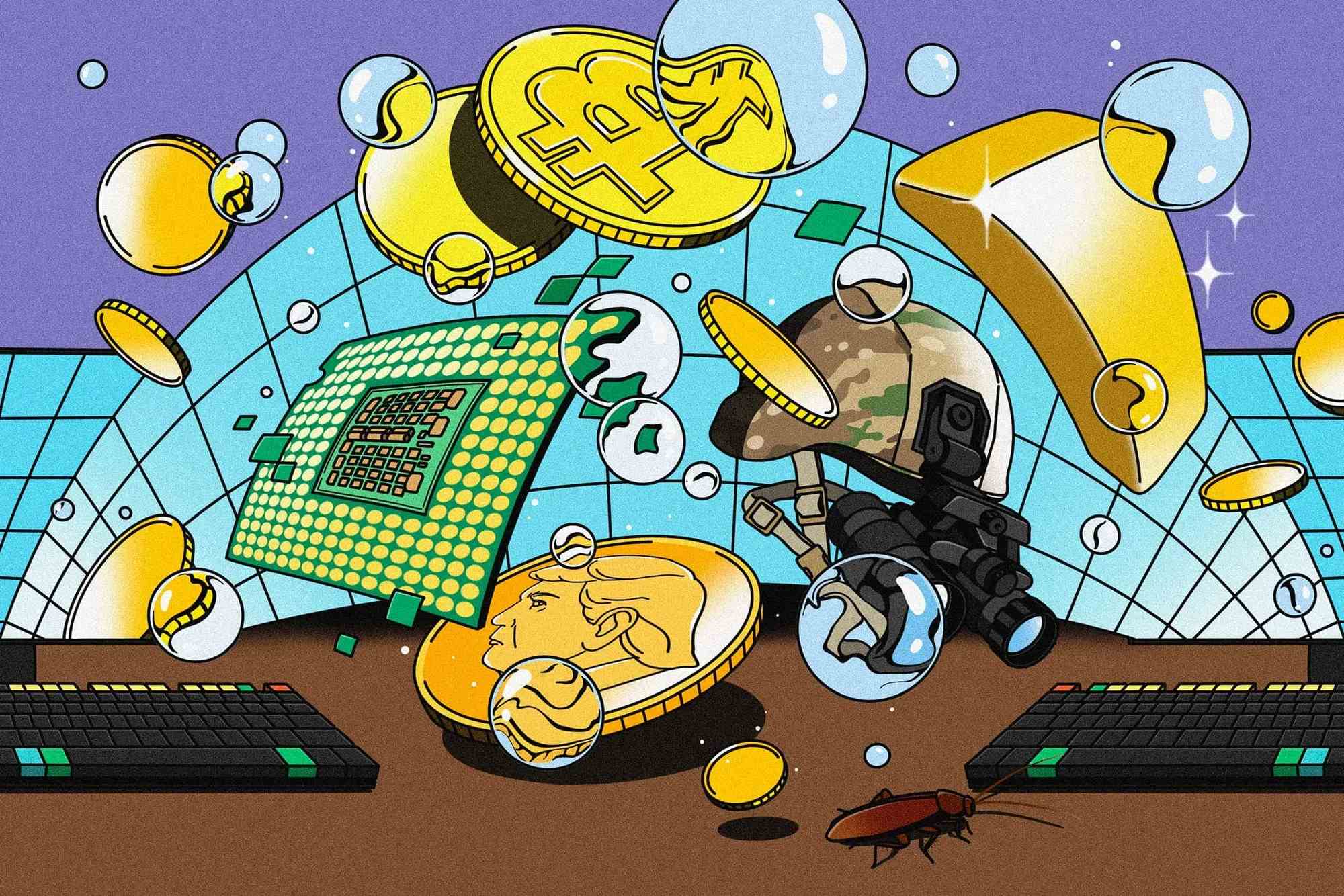

On October 11, Trump announced 100% tariffs on Chinese goods, triggering the largest liquidation event in cryptocurrency history. Beyond the $19–19.4 billion in liquidations, market makers may have sustained even more severe losses. Wintermute was forced to suspend trading due to risk control violations, while hedge funds like Selini Capital and Cyantarb lost between $18 million and $70 million. Institutions that normally profit steadily from providing liquidity saw months or even years of accumulated gains wiped out within 12 hours.

The most advanced quantitative models, the most robust risk systems, and the best market intelligence—all rendered useless in the face of a black swan. If even they couldn't escape, what chance do retail investors have?

Twelve days later, nearly the same script unfolded in another virtual world. On October 23, Valve introduced a new "upgrading mechanism" in CS2, allowing players to craft knife or glove skins using five rare-tier skins. This instantly altered the existing rarity structure: certain knife skins plummeted from tens of thousands to just a few thousand yuan, while previously overlooked rare-tier skins surged from around ten yuan to approximately 200 yuan. Merchants holding high-value inventories suddenly saw their investment portfolios shrink by over 50%.

Although I didn’t hold any expensive CS2 skins myself, I still felt the ripple effects of this crash in multiple ways: third-party skin marketplaces saw merchants rapidly pulling buy orders, causing transaction prices to collapse; short video platforms were flooded with videos of distressed merchants lamenting losses and cursing Valve, but mostly expressing confusion and helplessness in the face of such sudden changes.

Two seemingly unrelated markets displayed striking similarities: crypto market makers and CS2 skin merchants—one facing Trump’s tariff policy, the other confronting Valve’s rule changes—but both dying in almost identical ways.

This may also reveal a deeper truth: the profitability model of intermediaries inherently contains the seeds of systemic risk.

The Dual Traps Facing "Intermediaries"

The fundamental dilemma for intermediaries is that they must hold large inventories to provide liquidity, yet this very requirement exposes a fatal weakness during extreme market movements.

Leverage and Liquidation

A market maker’s profit model necessitates the use of leverage. In the crypto market, market makers must simultaneously provide liquidity across multiple exchanges, requiring significant capital. To improve capital efficiency, they typically employ 5–20x leverage. Under normal conditions, this system works well—small price fluctuations generate steady spread income, amplified by leverage.

But on October 11, this system met its ultimate nemesis: extreme volatility + exchange outages.

When extreme conditions hit, heavily leveraged positions held by market makers triggered mass liquidations. A flood of liquidation orders overwhelmed exchanges, causing system overloads and crashes. More critically, while exchange outages only cut off user interfaces, actual liquidations continued running behind the scenes—creating the most desperate scenario for market makers: watching their positions get liquidated without being able to add margin.

In the early hours of October 11, BTC, ETH, and other major cryptos plunged sharply. Some altcoins were even quoted at zero. Market makers’ long positions triggered forced liquidations → automatic sell-offs → intensified panic → further liquidations → exchange crashes → inability to buy back → even greater selling pressure. Once this cycle began, it became unstoppable.

The CS2 skin market lacks formal leverage and liquidation mechanisms, yet skin merchants face another structural trap.

When Valve updated the "upgrading mechanism," skin merchants had absolutely no warning. They excel at analyzing price trends, creating promotional content for expensive skins, and manipulating market sentiment—but none of this matters in the face of decisions made by the rule-setters.

Exit Mechanism Failure

Beyond leverage and structural flaws in their business models, the failure of exit mechanisms is another fundamental reason for massive losses among intermediaries. When a black swan hits, it’s precisely when the market needs liquidity the most—and when intermediaries most want to exit.

During the October 11 crypto crash, market makers held large long positions. To avoid liquidation, they needed to add margin or close positions. Their risk controls relied on the basic assumption that "trading is possible." But at that moment, overwhelming liquidation data caused servers to shut down entirely, cutting off their ability to act—leaving them helpless as their holdings were systematically liquidated.

In the CS2 skin market, liquidity depends on merchants injecting funds into the "buy order" books. Immediately after the update, retail users who spotted the news first quickly sold their skins into standing buy orders. By the time merchants realized what was happening, they had already incurred significant losses. If they joined the rush to sell, it would further devalue their remaining assets. Ultimately, these merchants found themselves trapped—unable to move forward or backward—becoming the biggest victims of market panic.

The "earn-the-spread" business model relies on liquidity, but during systemic crises, liquidity evaporates instantly—and intermediaries are precisely those holding the largest positions and needing liquidity the most. More fatally, the exit route fails exactly when it's needed most.

Lessons for Retail Investors

Within just two weeks, both popular virtual asset markets experienced the largest black swan events in their respective histories. This coincidence offers retail investors a crucial insight: strategies that appear stable often harbor the greatest risks.

Intermediary strategies yield steady small gains most of the time, but face massive losses during black swan events. This asymmetric return profile causes traditional risk metrics to severely underestimate true risk exposure.

This kind of profit strategy resembles picking up coins on a railway track—99% of the time you collect safely, but when the train comes in that 1%, there's no time to escape.

From a portfolio construction perspective, investors overly reliant on intermediary strategies must reassess their risk exposure. The losses suffered by crypto market makers during the black swan show that even market-neutral strategies cannot fully insulate against systemic risk. During extreme market moves, any risk model may fail.

More importantly, investors must recognize the significance of "platform risk." Whether it's an exchange changing its rules or a game developer altering mechanics, such shifts can instantly transform market dynamics. This type of risk cannot be fully mitigated through diversification or hedging—it can only be managed by reducing leverage and maintaining sufficient liquidity buffers.

For retail investors, these events offer actionable self-protection strategies. First, reduce dependence on "exit mechanisms," especially for high-leverage contract traders. In rapid downturns, even if you have funds to cover margin calls, you might not be able to execute in time—or at all.

No Safe Position, Only Reasonable Risk Compensation

$19 billion in liquidations. High-end skins dropping 70%. That money didn’t vanish—it simply transferred from the hands of those "earning spreads" to those controlling core resources.

In the face of a black swan, anyone without control over core resources is vulnerable—whether retail or institutional. Institutions lose more because their scale is larger; retail investors suffer more because they lack backup plans. Yet everyone is betting on the same thing: that the system won’t collapse on their watch.

You think you’re earning spreads, but in reality, you’re paying for systemic risk—and when the crisis hits, you may not even have the choice to walk away.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News