Understanding Rare Earths: China's "Ace Card" That Holds America's Neck

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Understanding Rare Earths: China's "Ace Card" That Holds America's Neck

This is not merely a resource embargo, but an industrial war lasting over 70 years.

The escalation of the China-U.S. trade friction is something everyone has probably seen. However, if you carefully read through those news reports and speeches, you might notice that this time, the focus seems different from the round in April.

The core issue in April was "trade deficit." This time, one term keeps surfacing: rare earths.

Even Trump posted two tweets in a row: "Unbelievable," "Unheard of."

You don’t need to read all these tweets—just understand one thing: the “rare earths” card truly troubles Trump.

Why rare earths? Aren't they just another mineral? And why do some people call this a "rare earth war"?

In fact, this isn’t just a resource embargo—it’s an industrial war spanning over 70 years.

To understand it, start with the most fundamental question.

Why Rare Earths?

Are rare earths really that important?

Extremely important. Today's high-tech and military industries cannot function without rare earths.

Here’s a concrete example: if China cuts off rare earth supplies, the U.S. F-35 fighter jet production will halt within six months. Within 18 months, seven out of ten aircraft in storage could become inoperable.

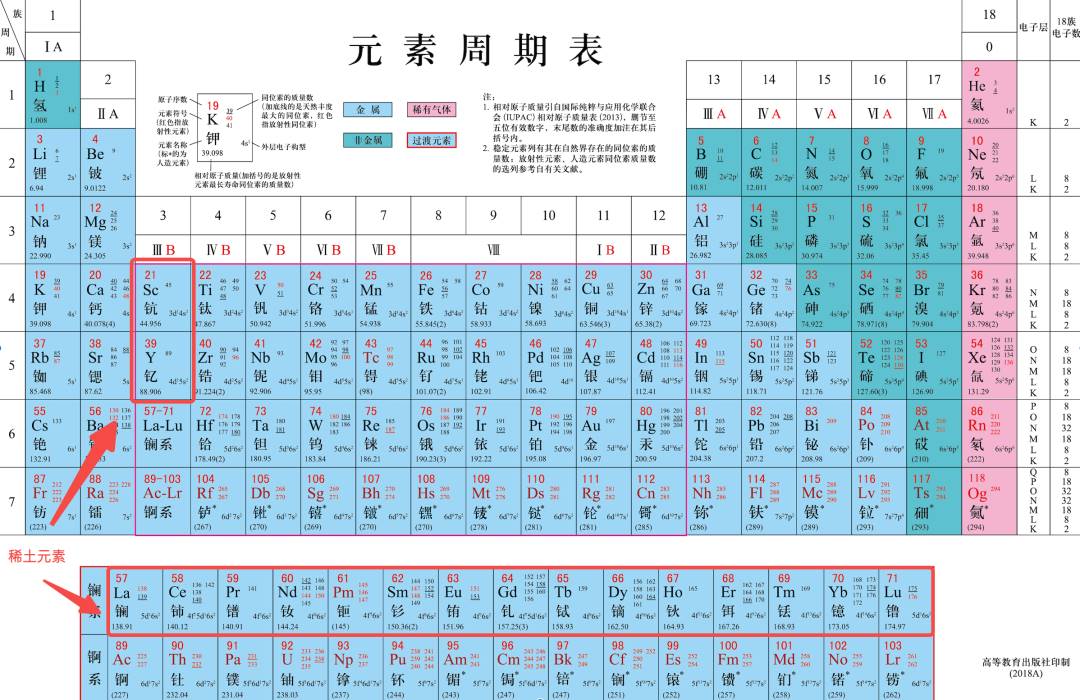

Chemically speaking, "rare earths" is a collective term for 17 chemical elements, each with unique functions.

This may sound abstract, so let me give a few examples.

Neodymium, dysprosium, and terbium can generate extremely strong magnetic fields in very small volumes—enabling smartphone speakers, computer hard drives, and electric vehicle motors.

Europium, terbium, yttrium, and neodymium can precisely convert electrical energy into light, sound, and vibration—making possible the vibrant colors on smartphone screens, audio playback from speakers, and haptic feedback in phone motors.

Neodymium, samarium, terbium, europium, and dysprosium enable weapons to see farther, hit accurately, and fly faster—powering the F-35 engine, missile guidance systems, and radar technology.

In short, from smartphone chips to missiles and aircraft carriers, rare earths are the key behind their critical components.

Does this mean rare earths are used in large quantities?

Quite the opposite—they're actually used in very small amounts. For example, only a few hundred grams (less than 0.1%) of rare earths are used in a ~400kg airborne AESA radar antenna. Similarly, only tens of kilograms are used in the core magnetic components of a ~5-ton shipborne phased array antenna.

In essence, rare earths are like salt—used sparingly, but essential. Without even a pinch, you can't cook. For America, the chef, the salt must come from China.

Because in rare earth manufacturing, China currently holds dominant advantages.

Consider this data: China accounts for about 69% of global rare earth refining and separation capacity, and over 90% of advanced processing capacity. In many critical areas, more than 90% of global output comes from China. Take rare-earth permanent magnet materials essential for military weapons: global production is 310,200 tons, with China producing 284,200 tons—91.62% of the total.

In other words, without China's supply system, the U.S. has no viable alternative in rare earth supply.

Now, what happens when the chef can’t buy salt?

Aircraft won’t immediately fall from the sky, but after exhausting several months of rare earth reserves, changes will emerge. According to a U.S. Congressional report, if China fully cuts off rare earth supplies, F-35 production lines could halt within six months. Within 18 months, only three out of ten aircraft might remain operational. Moreover, critical components like guidance systems and control chips would also face shortages, meaning repairs wouldn’t be possible either.

Unable to repair old equipment or produce new ones, rare earth supply cuts directly block U.S. military modernization.

The same situation applies to America's high-tech industry. The impact on consumer tech products would be even more noticeable—smartphones could become pricier, EV performance could degrade, and computer production could plummet.

Imagine the chef in America—facing such a bill, could he still sleep peacefully? Absolutely not.

Thus, the "rare earths" card is truly an "ace"—it allows China to hold America by the throat.

How Did It Come to This—China Holding America By the Throat?

You might wonder: we’ve always heard about the U.S. restricting us in chips and operating systems. How did the tables turn so dramatically?

This is precisely where the story becomes most fascinating.

Because China spent over 70 years turning what the U.S. once dismissed into our current advantage.

How was this achieved? Let’s walk through it step by step.

First, dispel a common misconception. Despite the name "rare earths," they aren’t actually rare.

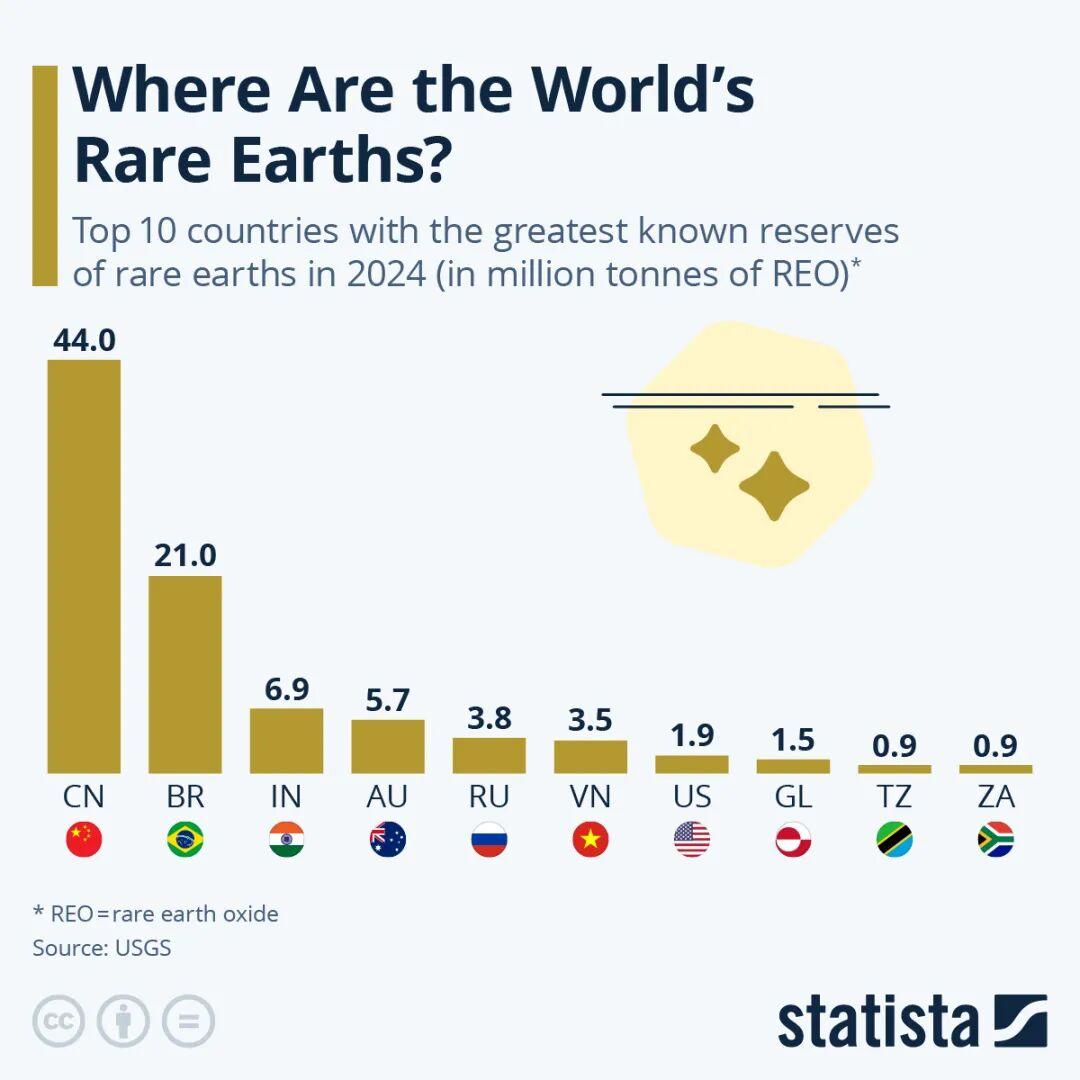

According to the U.S. Geological Survey 2024 data, while China holds the world’s largest rare earth reserves—about 34% globally—countries like Brazil, India, Australia, Russia, Vietnam, and the U.S. also possess significant deposits.

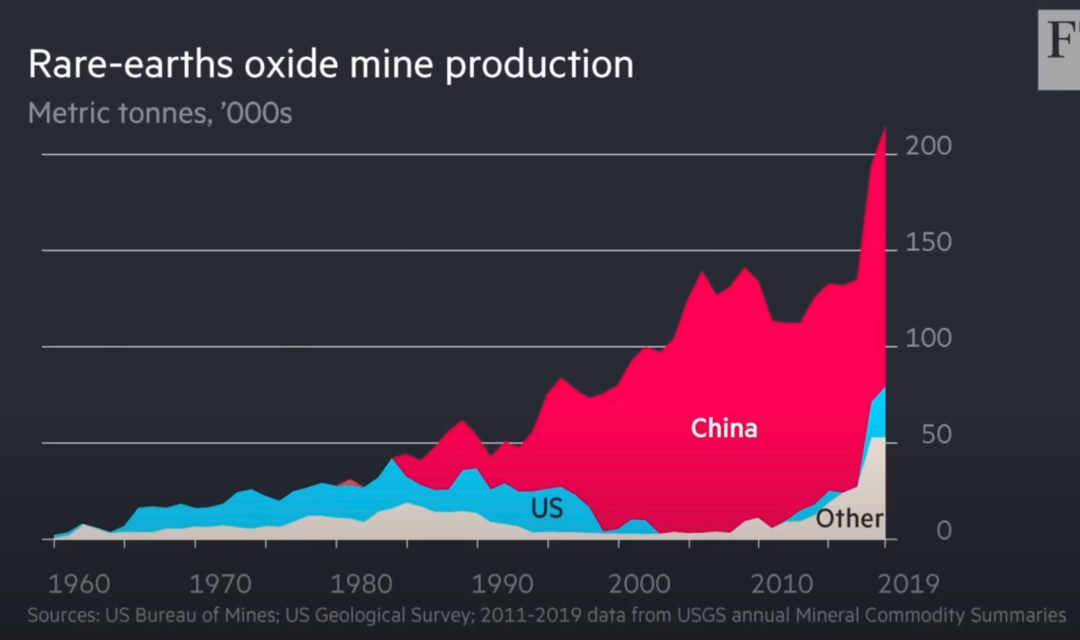

In fact, during the 1960s–70s, the U.S. dominated rare earth production—not only producing 70% to 90% of global output but also possessing the most advanced separation and purification technologies.

This shows the key to this "war" has never been who owns the biggest mine.

So why didn’t this leader maintain its dominance? Did it simply choose not to?

Exactly—you guessed it: the U.S. itself chose to abandon leadership.

The turning point came in the 1980s. Americans realized rare earth mining was rather "dirty." Production generated massive pollution—acids, heavy metals, even toxic fertilizers—and required enormous energy. With increasingly strict environmental laws, production costs soared.

Eventually, the U.S. calculated: domestic production meant complying with environmental regulations, paying high wages, and facing public complaints—costs were simply too high. Being the "leader" became too burdensome.

Solution? Outsource it! To whom? China. Studies suggest shifting rare earth production from the U.S. to China reduced unit costs by 30% to 70%.

At that time, China had massive cost advantages: abundant resources, plentiful low-cost labor, and relatively relaxed policies.

Thus, the gears of history began to turn.

In the 1980s–90s, numerous small and medium-sized rare earth enterprises sprang up like mushrooms. In 1985, China introduced tax rebate policies for rare earth exports, with rates ranging from 13% to 17% by the late 1990s and early 2000s.

This era could be described as "chaotic mining, wild growth." If you mined one hill, I’d mine two or three. If you sold at $10, I’d sell at $5—or even $3. Fierce competition drove rare earth prices down to白菜prices. Of course, there were costs—over-mining and environmental damage occurred in many areas.

The ultimate outcome of this "wild growth" was China becoming the world’s largest rare earth producer by the mid-to-late 1980s.

To Western nations, this was fantastic. They no longer needed to do dirty, expensive work—they could enjoy ultra-cheap rare earth products from China from the comfort of home.

So the U.S. ran another calculation: since importing was cheaper than domestic production, why bother producing at all? Thus, America’s largest rare earth mine, Mountain Pass, shut down.

Meanwhile, the global rare earth industry underwent restructuring—many Japanese and European rare earth companies either exited the market or downsized operations.

Through massive output and ultra-low costs, China effectively outlasted its global competitors.

But this was only the first half of the story.

At this stage, China hadn’t yet monopolized the entire industry—only leading in volume, not core technologies or pricing power.

Some might argue: wasn’t this just development at the expense of pollution? What’s impressive about that?

I say today’s Chinese rare earth industry has long moved beyond the "small workshop" model of high-pollution growth. It has evolved into a formalized, group-based national strategic industry.

The turning point came around 2010—the "national team" entered.

Step one: “Integration.”

Hundreds of small mines and factories nationwide were consolidated into “six major rare earth groups,” ending price wars and establishing full-process control from mining to export—halting reckless expansion and reducing environmental damage.

Step two: “Regulation.”

Stricter laws and policies were introduced—for example, rare earth production quotas starting in 2006, export taxes in 2007, and bans on exporting certain rare earth processing technologies in 2023.

Step three: “Technological Upgrading.”

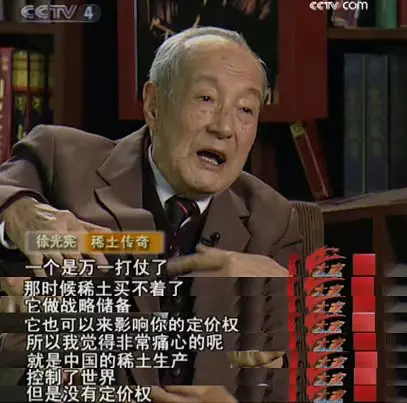

This was the most crucial step. Here we must mention Xu Guangxian, known as the “Father of Chinese Rare Earths.” His “rare earth cascade extraction theory” enabled production of 99.99%-pure single rare earth elements at lower cost.

Learning about Academician Xu Guangxian’s journey deeply moved me—this history is truly legendary.

In 1972, shortly after returning from a labor camp, Xu received an urgent mission: separate praseodymium and neodymium—the most difficult pair of “twin elements” in rare earths.

To 52-year-old Xu Guangxian, this wasn’t just a chemistry challenge—it concerned national economic sovereignty and defense security. Seeing China possess the world’s richest rare earth resources yet lack pricing power, he felt profound pain. He said:

“We felt deeply uncomfortable—so no matter how hard, we had to push forward.”

Thus began Xu Guangxian’s personal “war.”

Separating praseodymium and neodymium was a pivotal step in rare earth technology. At the time, the mainstream international method was “ion exchange”—like using tweezers to pick salt grains from sand. Feasible, but slow, expensive, and unsuitable for large-scale industrial use.

Xu Guangxian initially hit a dead end. What to do?

Unexpectedly, he opted for the then-high-risk “solvent extraction method.”

This method works like stacking dozens or hundreds of tiny filters, allowing rare earths to progressively “extract” and purify with each layer. Yet no company worldwide had succeeded with it.

Why did Xu dare attempt it?

Because he had previously worked on nuclear fuel extraction for the nation. Extraction was extraction—whether nuclear or rare earths.

Thus began Xu Guangxian’s expedition. By day, he labored in the lab, manually simulating industrial extraction via the primitive “shaking funnel” method. With processes involving dozens or hundreds of layers, one error ruined everything. Each person worked over 80 hours weekly. By night, Xu plunged into daytime data, performing endless calculations and simulations.

Finally, he discovered the “constant mixed extraction ratio law,” establishing the “cascade extraction theory.”

More impressively, based on this, Xu and his team developed a mathematical model with over 100 formulas. How powerful was this model? Factory technicians could input ore data and instantly obtain optimal production parameters. In short, it “dumbed down” the complex rare earth production process.

He didn’t just invent a new technology—he created an entire new system.

If technical breakthroughs demonstrated Xu Guangxian’s expertise, his subsequent actions revealed his admirable spirit.

In 1978, he founded the “National Cascade Extraction Training Course,” freely teaching the complete theory, formulas, and design methods to technicians nationwide. Quickly, a technology regarded as top-secret abroad became “common knowledge” even in rural Chinese workshops—laying the foundation for the later nationwide boom in rare earth industries.

In the early 1990s, China massively exported high-purity single rare earths, completely reshaping the global rare earth industry landscape.

You could say he transformed China’s rare earths from “sold by the ton” to “sold by the gram.”

To this day, China’s rare earth industry still rests on the achievements of Xu Guangxian’s “war.”

All these changes led to one tangible outcome: rare earth prices were drastically lowered.

For example, fighter jets contain a component called “phased array radar,” which uses “neodymium-iron-boron permanent magnets”—dependent on rare earths. In the 1990s, such radar systems cost millions of dollars.

Today, phased array radars are used in weather stations, automotive radar, and 5G base stations—costing only thousands of dollars, not millions.

Transforming complex military technology into ubiquitous civilian applications reflects the maturity of the rare earth industry.

China spent over 70 years evolving from a mere kitchen apprentice washing dishes into a master chef wielding unique culinary skills. About 90% of global refining, 93% of permanent magnet manufacturing, and 99% of heavy rare earth processing now occur in China.

Interestingly, for decades, China’s surging share of the global rare earth market went largely unnoticed by Western nations.

I couldn’t help wondering: with things so obvious, did no one see it coming? Online analyses suggest the main reason was China’s dirt-cheap raw materials and abundant supply. Environmentally conscious Western nations saw no need to rebuild their own rare earth industries.

In short, as long as supplies were sufficient and cheap, no one worried about running out.

This comfortable life lasted until 2010.

Japan faced a near two-month rare earth supply cut-off, causing prices to skyrocket—some by over tenfold.

Suddenly, everyone realized something was terribly wrong.

Shortly after, the U.S. restarted its sole domestic rare earth mine, Mountain Pass, while seeking alternative suppliers in Japan and Australia.

But the U.S. lacked rare earth refining technology. Even domestically mined rare earths still had to be shipped to China for refining.

Underground reserves don’t guarantee dominance—it’s actual production capacity and technology in hand that matter.

This explains how the tide turned within just 70 years.

Now you might ask: since everyone knows rare earths are vital and has finally woken up, why don’t they catch up quickly?

If Rare Earths Are So Important, Why Don’t Other Countries Develop Their Own?

Actually, anyone can try—but it would take at least 10 years to establish a competitive industry.

Rare earth technology isn’t cutting-edge; the U.S. mastered it long ago. But building a self-sufficient industry requires a complete set: capital, talent, technology, and environmental management.

Let’s examine each.

First, capital barriers.

How much does it cost to build just one rare earth separation plant?

Take Australia’s Lynas—the world’s second-largest rare earth producer after China. Its separation plant in Malaysia has cumulatively cost over $1 billion. That’s just one facility. Building a full supply chain—from mines to smelters to processors—would require tens or even hundreds of billions of dollars and at least 5–10 years.

For investors, this carries too much risk and too slow a return. Who’s willing to wait?

Second, technological barriers.

The challenge isn’t theoretical knowledge, but replicable “process know-how.”

For example, the “solvent extraction” step in rare earth separation is extremely demanding. You must pass rare earth solutions through hundreds or even a thousand extraction tanks, each requiring precise pH control—with tolerances of mere fractions.

Imagine making an error at tank #131 without realizing it—only discovering the mistake after completing 800 subsequent steps. Would you be frustrated?

The only way to ensure success is through relentless experimentation and data accumulation.

In short, it’s like a chef saying “a pinch of salt, a spoon of vinegar, simmer on low heat.” But how many milligrams is “a pinch”? How big is the “spoon”? What temperature is “low heat” for how long? Ask the chef, and he’ll say these are “muscle memory” and “personal touch” built over years. All true—no deception here.

Countries like Vietnam and Brazil, despite rich rare earth deposits, either lack technology and a full industrial system or must import equipment from China. Their dilemma mirrors that of many nations: even with the “recipe,” they can’t read it or lack the “cooking tools.”

As of 2023, among 469,758 rare earth patents retrieved from Incopat, China holds 222,754—about 47.4%, maintaining global leadership. Experts estimate China’s separation technology leads overseas counterparts by at least 5–10 years.

Third, talent barriers.

Harder than technology to replicate is human expertise. Western nations face a nearly two-generation talent gap in rare earths.

How long to train experts from scratch?

A rare earth expert typically needs 10 to 15 years—from undergraduate studies to PhD and practical industry experience. Supporting a complete industrial chain requires teams of hundreds such experts.

Another harsh reality: no teachers, no students. The most knowledgeable experts have likely retired, creating a knowledge gap. As for students, with rare earth industries gone in Western countries for thirty years, how many would choose this “niche” field?

Fourth, policy barriers.

Even if talent, technology, and funding are solved, the public’s environmental concerns remain unavoidable.

Back then, residents complained about noise and pollution. Today, public backlash would likely be far stronger.

This may be the hardest hurdle for Western nations to overcome.

So back to the original question: why don’t other countries develop their own rare earth industries?

It’s not that they don’t want to—it’s that they can’t. Even if they start now, it would take 10 to 20 years to cover the 70-year path China has traveled.

Look at the U.S.: despite restarting Mountain Pass, it still lacks skilled workers, policy support, and sufficient refining capacity. Mountain Pass is expected to produce 1,000 tons of neodymium-iron-boron magnets by end-2025—less than 1% of China’s 138,000-ton 2018 output.

Experts predict that at current progress, the U.S. may not achieve rare earth self-sufficiency until 2040.

But that’s 15 years away—while the current “rare earth war” has already begun.

Final Thoughts

Phew, that’s it. By now, you should understand what rare earths are all about and why they can hold America by the throat.

The phrase “the wheel of fortune turns” sounds easy, but behind it lies generations of effort over seventy grueling years.

Today, we can play the rare earth “ace” only because countless predecessors paid an immense price to forge this card for us.

When the U.S., driven by commercial logic, discarded this dirty, labor-intensive industry like worn-out shoes, scientists like Xu Guangxian bent down and picked up this “legacy”—now seen as incredibly valuable.

In an era of extreme scarcity, they devoted their lives to humble labs, pouring their passion into what outsiders saw as dull test tubes and flasks. It was this perseverance, faith, and determination that turned “dirt” into “gold.”

It also bears the immense sacrifices of countless industrial workers—those who dug through clouds of dust, stood guard beside pungent chemical baths, and built this industry’s absolute advantage, drop by drop, with sweat and sacrifice.

There was no accidental success, no unearned strength. The confidence and leverage we have today to stand eye-to-eye with the U.S. exist only because a group of people bore the heaviest burdens and endured the greatest hardships for us in the past—turning a losing hand into a royal flush.

They are the true “aces” behind the “rare earths” card. And they are the ones we should thank most today.

Because the history we witness today is precisely the echo of history past.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News