Vitalik's new article: When technology controls everything, openness and verifiability become necessities

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik's new article: When technology controls everything, openness and verifiability become necessities

When technology deeply intervenes in life and freedom, how can we avoid a "digital dystopia"?

Author: Vitalik

Translation: TechFlow

Introduction

In this new article published on September 24, 2025, Vitalik Buterin explores a critical issue shaping all our futures: as technology increasingly takes over our lives, how do we preserve autonomy?

The article opens by identifying the defining trend of the century—"the internet has become real life."

From instant messaging to digital finance, from health tracking to government services, and even future brain-computer interfaces, digital technologies are reshaping every dimension of human existence. Vitalik argues this trend is irreversible because, in global competition, civilizations rejecting these technologies will lose competitiveness and sovereignty.

But widespread technology adoption brings profound shifts in power structures. Those who benefit most from technological waves are not consumers but producers. As we place increasing trust in technology, any breach—such as backdoors or security flaws—could have catastrophic consequences. More importantly, even the mere possibility of such breaches forces society into exclusive trust models, prompting questions like "Was this built by someone I trust?"

Vitalik’s solution is clear: we need two interrelated properties across the entire technology stack (software, hardware, and even biotechnology): true openness (open source, free licensing) and verifiability (ideally directly verifiable by end users).

The article illustrates through concrete examples how these two principles support each other in practice, and why one alone is insufficient. Below is the full translation.

Special thanks to Ahmed Ghappour, bunnie, Daniel Genkin, Graham Liu, Michael Gao, mlsudo, Tim Ansell, Quintus Kilbourn, Tina Zhen, Balvi volunteers, and GrapheneOS developers for their feedback and discussions.

Perhaps the biggest trend of this century so far can be summarized in one sentence: "The internet has become real life." It began with email and instant messaging. Private conversations that for millennia happened via mouth, ears, and paper now run entirely on digital infrastructure. Then came digital finance—both crypto-finance and the digitization of traditional finance itself. Then came our health: thanks to smartphones, personal health-tracking watches, and data inferred from purchase records, information about our bodies is now processed through computers and computer networks. In the next twenty years, I expect this trend to extend into many other domains, including various government processes (eventually even voting), monitoring physical and biological indicators and threats in the public environment, and ultimately, through brain-computer interfaces, even our thoughts.

I don’t believe these trends are avoidable; their benefits are too great, and in a highly competitive global environment, civilizations that reject these technologies will first lose competitiveness, then sovereignty, to those embracing them. Yet, beyond offering powerful benefits, these technologies profoundly reshape power dynamics, both within and between nations.

The civilizations benefiting most from new technological waves are not those consuming the technology, but those producing it. Equal-access programs to centralized platforms and APIs provide at best a small fraction of the benefit and fail outside predetermined “normal” conditions. Moreover, this future requires placing enormous trust in technology. If that trust is broken (e.g., backdoors, security failures), we face serious problems. Even just the possibility of broken trust forces people back into fundamentally exclusive social trust models (“Was this built by someone I trust?”). This creates upward incentives: sovereignty lies with those who decide exceptional states.

Avoiding these issues requires the entire technology stack—software, hardware, and biotechnology—to possess two intertwined properties: true openness (i.e., open source, including free licensing) and verifiability (ideally, directly verifiable by end users).

The internet is real life. We want it to be a utopia, not a dystopia.

The Importance of Openness and Verifiability in Health

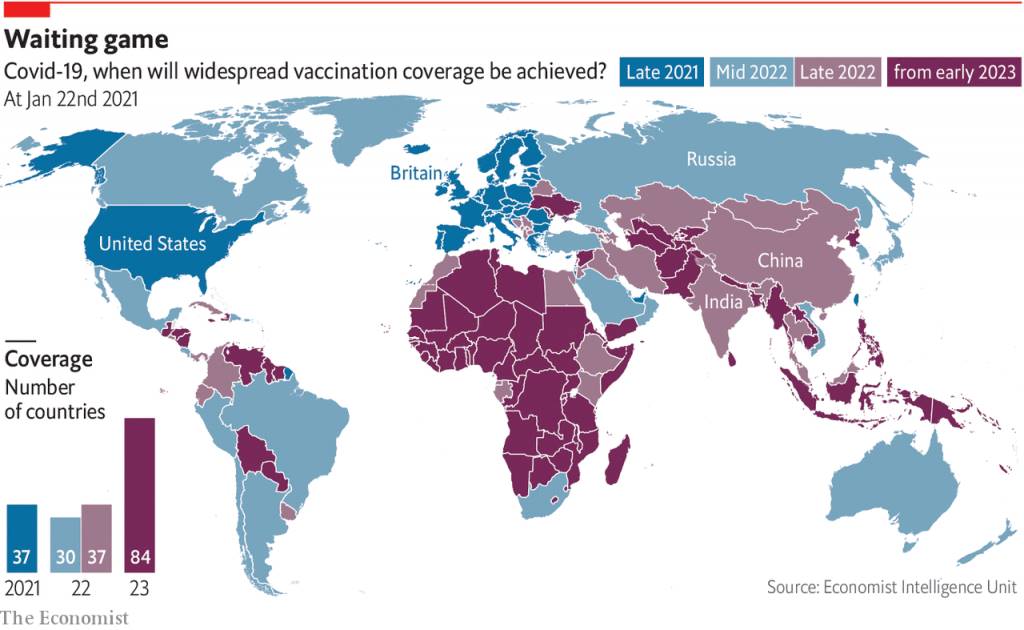

We saw the consequences of unequal access to technological means of production during the COVID pandemic. Vaccines were produced in only a few countries, leading to huge disparities in when different countries could access them. Wealthier nations received high-quality vaccines in 2021, while others received lower-quality ones in 2022 or 2023. There were efforts to ensure equal access, but they could only go so far because vaccine designs relied on capital-intensive proprietary manufacturing processes limited to a few locations.

Covid vaccine coverage, 2021–2023.

A second major problem with vaccines was lack of transparency. Scientific and communication strategies attempted to convince the public that vaccines carried zero risk or drawbacks—an unrealistic claim that ultimately greatly exacerbated distrust. Today, this distrust has evolved into rejection of half a century of science.

In fact, both problems are solvable. Vaccines funded by Balvi, like PopVax, cost less to develop and are manufactured through more open processes, reducing access inequality while making safety and efficacy easier to analyze and verify. We could go further by designing verifiable vaccines.

Similar issues apply to the digital aspects of biotechnology. When you speak with longevity researchers, one of the first things you hear universally is that the future of anti-aging medicine is personalized and data-driven. To know today which drugs and nutritional changes to recommend to a person, you need to understand their body's current state. This becomes even more effective if vast amounts of data can be collected and processed digitally in real time.

The data collected by this watch is 1000x that of Worldcoin. That has both advantages and disadvantages.

The same idea applies to defensive biotechnologies aimed at preventing downside risks, such as fighting pandemics. The earlier a pandemic is detected, the more likely it can be contained at the source—even if not, more time is gained weekly to prepare and initiate countermeasures. While a pandemic continues, knowing where people are getting sick has great value for deploying countermeasures in real time. If an average infected person learns they’re sick and self-isolates within an hour, transmission drops significantly compared to spreading it for three days. If we know which 20% of locations are responsible for 80% of transmission, improving air quality there can yield further gains. All this requires (i) many, many sensors, and (ii) the ability for sensors to communicate in real time to deliver information to other systems.

If we go further in the “science fiction” direction, brain-computer interfaces could enable higher productivity, help people better understand each other through telepathic communication, and open safer pathways to highly intelligent AI.

If the infrastructure for personal and spatial health tracking is proprietary, data defaults to falling into the hands of large corporations. These companies can build various applications atop it, while others cannot. They may offer API access, but such access would be restricted, used for rent extraction, and potentially revoked at any time. This means a few individuals and companies gain control over the most important components of 21st-century technology, limiting who can benefit economically.

On the other hand, if this personal health data is insecure, hackers could blackmail you over any health issue, optimize pricing of insurance and healthcare products to extract value from you, and—if data includes location tracking—know where to wait to kidnap you. Conversely, your location data (very frequently hacked) can be used to infer information about your health. If your brain-computer interface is hacked, hostile actors could literally read (or worse, write into) your thoughts. This is no longer science fiction: see here for a plausible attack where a BCI hack could cause someone to lose motor control.

In summary, there are huge benefits, but also significant risks: high emphasis on openness and verifiability is well-suited to mitigating these risks.

The Importance of Openness and Verifiability in Personal and Commercial Digital Technology

Earlier this month, I had to fill out and sign a form required for a legal function. At the time, I wasn’t in town. There was a national e-signature system, but I hadn’t set it up yet. I had to print the form, sign it, walk to a nearby DHL, spend considerable time filling out paper forms, and then pay to have the document shipped to the other side of the Earth. Time required: half an hour. Cost: $119. On the same day, I had to sign a (digital) transaction to execute on the Ethereum blockchain. Time required: 5 seconds. Cost: $0.10 (fairly speaking, without blockchain, signing could be completely free).

Stories like this are easy to find in areas like corporate or nonprofit governance, intellectual property management. Over the past decade, you could find them in promotional materials for a large portion of blockchain startups. Beyond that, there’s the mother of all use cases for “exercising personal power digitally”: payments and finance.

Of course, all this comes with major risks: what if software or hardware gets hacked? This is a risk long recognized in the crypto space: blockchains are permissionless and decentralized, so if you can’t access your funds, there are no resources and no uncle in the sky to turn to. Not your keys, not your coins. For this reason, the crypto space early on started exploring multisignature wallets, social recovery wallets, and hardware wallets. However, in reality, in many cases, the absence of a trusted uncle in the sky isn’t an ideological choice but an inherent part of the scenario. Indeed, even in traditional finance, the “uncle in the sky” fails to protect most people: for example, only 4% of scam victims recover losses. In use cases involving personal data custody, leakage cannot be recovered even in principle. Therefore, we need true verifiability and security—for software and ultimately hardware.

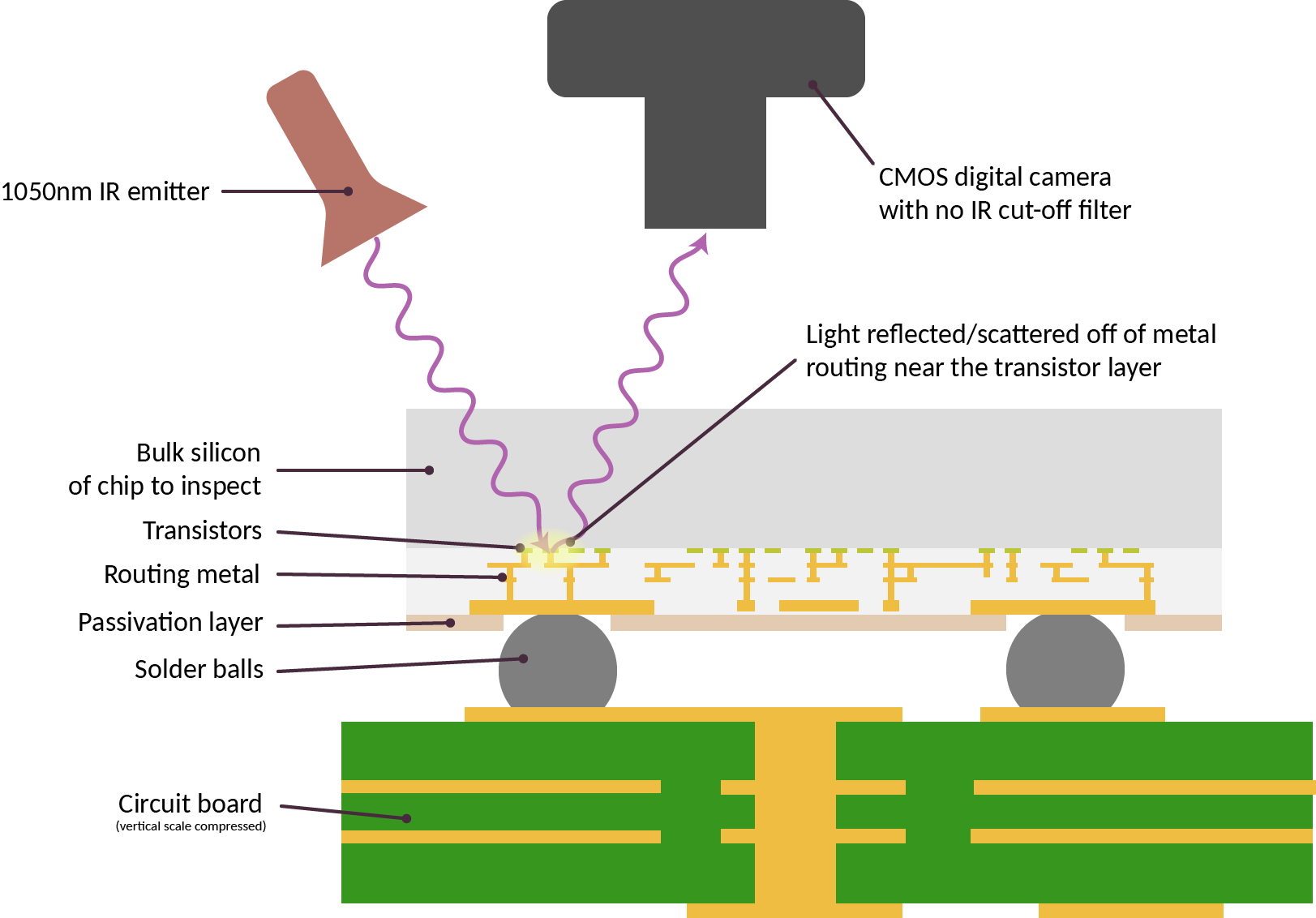

A proposed technique for inspecting silicon chips to verify correct manufacturing.

Importantly, regarding hardware, the risks we aim to prevent go far beyond “Is the manufacturer evil?” Instead, the issue is the vast number of dependencies, most of which are closed-source, where any single oversight could lead to unacceptable security outcomes. This paper shows a recent example of how microarchitectural choices can undermine side-channel resistance designed to be provably secure under software-only models. Attacks like EUCLEAK rely on vulnerabilities harder to detect due to the number of proprietary components. If AI models are trained on compromised hardware, backdoors can be inserted during training.

Another issue across all these cases is the downside of closed and centralized systems, even if they are fully secure. Centralization creates persistent leverage between individuals, companies, or nations: if your core infrastructure is built and maintained by a potentially untrustworthy company in a potentially untrustworthy country, you're vulnerable to pressure (see Henry Farrell on weaponized interdependence). This is exactly what cryptocurrency aims to solve—but it exists in far more domains than just finance.

The Importance of Openness and Verifiability in Digital Civic Technology

I often talk to people across sectors trying to identify better forms of government suited to different 21st-century environments. Some, like Audrey Tang, aim to elevate existing political systems by empowering local open-source communities and using mechanisms like citizens’ assemblies, sortition, and quadratic voting. Others start from scratch: here’s a constitution recently proposed by some Russia-born political scientists for Russia, with strong protections for individual freedom and local autonomy, institutional bias toward peace and against aggression, and unprecedentedly strong roles for direct democracy. Others, like economists working on land value tax or congestion pricing, are trying to improve their nation’s economy.

Different people may feel varying degrees of enthusiasm for each idea. But they all share one thing: they involve high-bandwidth participation, so any realistic implementation must be digital. Pen and paper suffice for very basic records of ownership or elections held every four years, but not for anything requiring higher bandwidth or frequency of input.

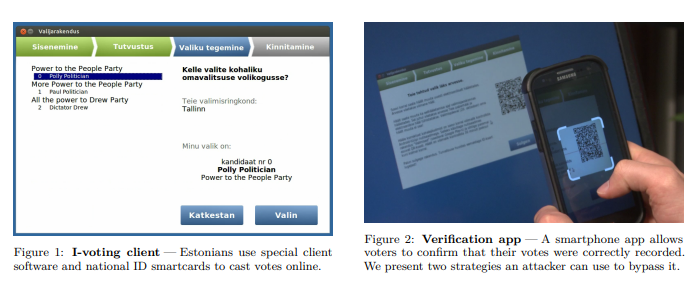

Historically, however, security researchers have ranged from skeptical to hostile toward ideas like electronic voting. Here’s a good summary of arguments against electronic voting. Quoting the document:

First, the technology is a “black box software,” meaning the public does not have access to the software controlling voting machines. Although companies protect their software to prevent fraud (and beat competitors), this also leaves the public unaware of how voting software works. The company could easily manipulate the software to produce fraudulent results. Additionally, machine vendors compete with each other and cannot guarantee their machines serve voters’ best interests or ballot accuracy.

There are many real-world cases validating these suspicions.

A critical analysis of Estonia’s internet voting, 2014.

These arguments apply word-for-word to many other scenarios. But I predict that as technology advances, the reaction “we just won’t do this” will become increasingly unrealistic across broad domains. As technology makes the world rapidly more efficient (for better or worse), I expect any system failing to follow this trend will become increasingly irrelevant to personal and collective affairs. Thus, we need an alternative: actually doing the hard thing—figuring out how to make complex technological solutions safe and verifiable.

Theoretically, “secure and verifiable” and “open source” are distinct concepts. Something could absolutely be proprietary and secure: aircraft are highly proprietary technologies, yet commercial aviation is generally a very safe way to travel. But proprietary models cannot achieve common knowledge of security—the ability to be trusted by mutually distrustful participants.

Civic institutions like elections are a classic case where common knowledge of security matters. Another is evidence collection for courts. Recently in Massachusetts, a large amount of breathalyzer evidence was ruled inadmissible because information about faults in testing was found to have been concealed. Quoting the article:

Wait, so were all the results wrong? No. In fact, in most cases, breathalyzer tests didn’t have calibration issues. However, because investigators later discovered the state crime lab withheld evidence indicating the problem was more widespread than claimed, Judge Frank Gaziano wrote that all defendants’ due process rights were violated.

Court due process essentially demands not just fairness and accuracy, but common knowledge of fairness and accuracy—because without confidence that the court is acting correctly, society easily descends into vigilante justice.

Beyond verifiability, openness itself has intrinsic benefits. Openness allows local groups to design systems for governance, identity, and other needs in ways compatible with local goals. If voting systems are proprietary, nations (or provinces or towns) wanting to experiment with new systems face difficulty: they must either convince companies to implement desired rules as features, or rebuild everything from scratch and ensure its security. This raises the high cost of political innovation.

In any of these areas, a more open-source, hacker-ethic approach would put more agency in the hands of local implementers, whether acting as individuals or as parts of governments or companies. To achieve this, open tools for building must be widely available, and infrastructure and codebases must be freely licensed to allow others to build atop them. To the extent that minimizing power differences is a goal, copyleft is especially valuable.

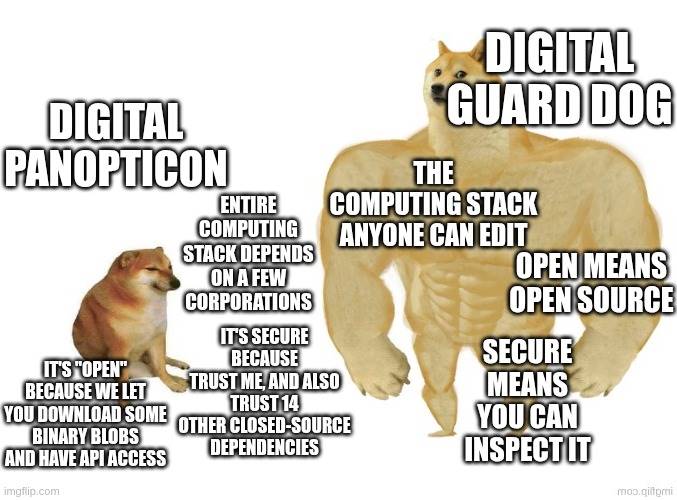

The final major area of civic technology in the coming years will be physical security. Surveillance cameras have sprouted everywhere over the past two decades, raising civil liberty concerns. Unfortunately, I predict recent drone warfare will make “not doing high-tech security” no longer viable. Even if a nation’s own laws don’t infringe on individual liberties, if the nation can’t protect you from other nations (or rogue companies or individuals) imposing their laws on you, drones make such attacks easier. Thus, we need countermeasures, possibly involving numerous anti-drone systems, sensors, and cameras.

If these tools are proprietary, data collection will be opaque and centralized. If they’re open and verifiable, we can pursue better approaches: security devices provably outputting only limited data under specific conditions, deleting the rest. We can envision a digital physical security future that’s more like a digital watchdog than a digital panopticon. One could imagine a world where public surveillance devices are legally required to be open source and verifiable, and anyone has the legal right to randomly select and disassemble a public camera to verify it. University computer science clubs could routinely do this as an educational exercise.

Paths Toward Open and Verifiable Systems

We cannot avoid digital computing being deeply embedded in every aspect of our (personal and collective) lives. By default, we might get digital systems built and operated by centralized corporations, optimized for profit motives of a few, backdoored by their host governments, and inaccessible to most of the world in terms of creation or security verification. But we can strive for better alternatives.

Imagine a world:

-

You own a secure personal electronic device—with phone functionality, security and inspectability comparable to a hardware wallet, approaching the precision of a mechanical watch.

-

All your messaging apps are encrypted, message patterns obfuscated by mixnets, and all code formally verified. You can be confident your private communications are truly private.

-

Your finances consist of standardized ERC20 assets on-chain (or on a server publishing hashes and proofs on-chain to guarantee correctness), managed by a wallet on your personal device. If you lose the device, recovery is possible via a combination (chosen by you) of your other devices, family, friends, or institutions (not necessarily governments: even churches could plausibly offer this service if accessible to all).

-

An open-source version of Starlink-like infrastructure exists, enabling robust global connectivity without dependence on a few individual players.

-

You have on-device open-weight LLMs scanning your activities, providing suggestions and task automation, and warning you when you might receive misinformation or are about to make a mistake.

-

The operating system is also open source and formally verified.

-

You wear a 24/7 personal health tracker that is also open source and inspectable, allowing you to access your data and ensuring no one else accesses it without consent.

-

We have more advanced governance forms, using combinations of sortition, citizens’ assemblies, quadratic voting, and clever democratic mechanisms to set goals, plus methods to select expert proposals for achieving them. As a participant, you can genuinely trust the system implements rules you understand.

-

Public spaces are equipped with monitoring devices tracking biological variables (e.g., CO2 and AQI levels, airborne diseases, wastewater). Yet these devices (along with any surveillance cameras and defensive drones) are open source and verifiable, with legal frameworks allowing public random inspection.

In this world, we enjoy greater security, freedom, and equal access to the global economy. Achieving it, however, requires greater investment in various technologies:

-

More advanced forms of cryptography. What I call Egyptian god-tier cryptography—ZK-SNARKs, fully homomorphic encryption, and obfuscation—are powerful because they let you compute over data in multi-party contexts while guaranteeing outputs, all while keeping data and computation private. This enables many stronger privacy-preserving applications. Adjacent tools to cryptography (e.g., blockchains providing strong guarantees against data tampering and user exclusion, differential privacy adding noise to further protect privacy) also apply here.

-

Application and user-level security. Applications are only secure if their security guarantees can actually be understood and verified by users. This involves software frameworks making strongly secure applications easy to build. Crucially, it also involves browsers, operating systems, and other intermediaries (e.g., locally running observer LLMs) each doing their part to verify applications, assess risk levels, and present this information to users.

-

Formal verification. We can use automated proof methods to algorithmically verify whether programs satisfy properties we care about, e.g., not leaking data or resisting unauthorized third-party modification. Lean has recently become a popular language. These techniques are already being used to verify ZK-SNARK proof algorithms for the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) and other high-value, high-risk use cases in cryptography, and should expand similarly into broader domains. Beyond this, we need further progress in other more mundane security practices.

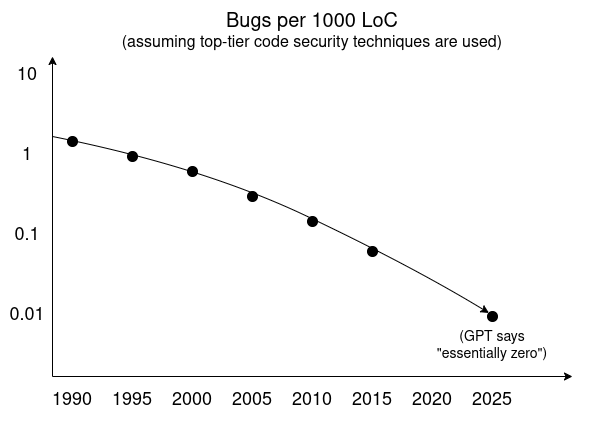

Cybersecurity fatalism of the 2000s was wrong: bugs (and backdoors) can be defeated. We “just” need to learn to prioritize security over other competing goals.

-

Open-source and security-focused operating systems. Growing examples include: GrapheneOS as a security-centric Android variant, security-focused minimal kernels like Asterinas, and Huawei’s HarmonyOS (which has an open-source version) that uses formal verification (many readers may think “if it’s Huawei, it surely has backdoors,” but this misses the point: who produces something doesn’t matter, as long as it’s open and anyone can verify it. This is a prime example of how openness and verifiability counter global balkanization)

-

Secure open-source hardware. No software is secure if you can’t confirm your hardware is truly running it and not secretly leaking data. My two main short-term goals in this area are:

-

Personal secure electronics—what blockchain folks call “hardware wallets” and open-source enthusiasts call “secure phones,” though once you account for security and general-purpose needs, both converge toward the same thing.

-

Physical infrastructure in public spaces—smart locks, the bio-monitoring devices described above, and general “Internet of Things” tech. We need to be able to trust them. This requires openness and verifiability.

-

-

Secure open toolchains for building open-source hardware. Today, hardware design relies on a series of closed-source dependencies. This greatly increases hardware production costs and makes the process more restrictive. It also renders hardware verification impractical: if chip-design tools are closed source, you don’t know what to verify against. Even existing tools like scan chains often can’t be used in practice because too many essential tools are closed source. This can change.

-

Hardware verification (e.g., IRIS and X-ray scanning). We need methods to scan chips and verify they contain the intended logic and lack extra components enabling covert tampering or data extraction. This can be done destructively: auditors randomly order products containing chips (using seemingly average end-user identities), then disassemble and verify the logic matches. With IRIS or X-ray scanning, it can be non-destructive, allowing potential scanning of every chip.

-

To achieve consensus trust, ideally a large group of people should be able to use hardware verification techniques. Today’s X-ray machines aren’t there yet. This can improve in two ways. First, we can enhance verification equipment (and chip verifiability) for wider accessibility. Second, we can supplement “full verification” with more limited forms, even performable on smartphones (e.g., ID tags and key signatures from physical unclonable functions), verifying narrower claims like “Is this device part of a batch produced by a known manufacturer, where known random samples have already undergone detailed third-party verification?”

-

Open-source, low-cost, local environmental and bio-monitoring devices. Communities and individuals should be able to measure their environment and themselves, identifying biological risks. This includes diverse form factors: personal medical devices like OpenWater, air quality sensors, universal airborne disease sensors (e.g., Varro), and large-scale environmental monitoring.

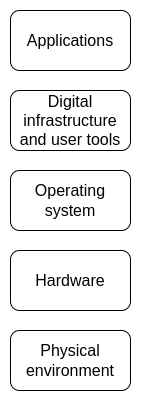

Openness and verifiability matter at every layer of the stack.

Getting From Here to There

A key difference between this vision and more “traditional” technological visions is its friendliness to local sovereignty, individual empowerment, and freedom. Security isn’t achieved by searching the entire world to ensure no bad actors exist anywhere, but by making the world resilient at every level. Openness means openly building and improving every layer of technology, not just centrally planned open-access API programs. Verification isn’t the exclusive privilege of proprietary rubber-stamp auditors likely colluding with the companies and governments deploying the technology—it’s a right and a socially encouraged hobby.

I believe this vision is more robust and better aligned with our fragmented global 21st century. But we don’t have infinite time to realize it. Centralized security approaches are advancing rapidly—collecting more centralized data, inserting more backdoors, and reducing verification to “this was made by a trusted developer or manufacturer.” For decades, attempts have been made to substitute centralized models for true open access. It perhaps began with Facebook’s internet.org, and will continue, each attempt more sophisticated than the last. We must act swiftly to compete with these approaches and openly demonstrate to people and institutions that better solutions are possible.

If we succeed in realizing this vision, one way to understand the resulting world is as retro-futurist. On one hand, we benefit from more powerful technologies enabling improved health, more effective and resilient self-organization, and protection against old and new threats. On the other hand, we regain attributes that were second nature in 1900: infrastructure is free, people can freely disassemble, verify, and modify it for their needs, anyone can participate—not just as consumers or “app builders”—at any layer of the stack, and anyone can be confident devices do exactly what they claim.

Designing for verifiability has costs: many hardware and software optimizations bring high-speed gains at the expense of making designs harder to understand or more fragile. Open source makes monetization under many standard business models more challenging. I believe both issues are overstated—but this isn’t something the world will believe overnight. This leads to the question: what are pragmatic short-term goals?

I propose one answer: work to build a fully open-source and verification-friendly stack targeted at high-security, non-performance-critical applications—including both consumer and institutional, remote and in-person use cases. This would encompass hardware, software, and biotechnology.

Most computing that truly requires security doesn’t actually require speed; and even when speed is needed, there are often ways to combine high-performance but untrusted components with trusted but slower ones to achieve high performance and trust for many applications. Achieving maximum security and openness everywhere isn’t realistic. But we can first ensure these properties are available in domains where they matter most.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News