Vitalik's latest post: Open source as the third path to mitigate technological centralization is being underestimated

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik's latest post: Open source as the third path to mitigate technological centralization is being underestimated

As technology advances, technological centralization is intensifying, while open source serves as an effective way to reduce power concentration and information asymmetry.

Author: Vitalik Buterin

Compiled & Translated: Janna, ChainCatcher

ChainCatcher has compiled and translated the content (with abridgments).

Key Points:

-

Radical technologies may exacerbate social inequality as the wealthy and powerful gain easier access, widening gaps in lifespan and advantages between rich and poor, potentially creating a global underclass.

-

Another form of technological abuse occurs when manufacturers exert power over users through data collection and information concealment—distinct in nature from unequal access to technology.

-

Open source is an underappreciated third path that can improve both access equality and producer equality in technology, enhance verifiability, and eliminate vendor lock-in.

-

Critics argue open source increases misuse risks, but centralized gatekeepers are untrustworthy and prone to abuse for military purposes, with little assurance of equitable access across nations.

-

If a technology carries high misuse risk, a better solution may be not doing it at all; if discomfort stems from power dynamics, open sourcing it could make it fairer.

-

Open source does not imply laissez-faire—it can be combined with legal frameworks, with the core goal being democratization of technology and accessibility of information.

A common concern we often hear is that certain radical technologies might exacerbate power inequality because they inevitably become limited to use by the wealthy and elite.

Below is a quote from someone concerned about the consequences of life extension:

"Will some people be left behind? Will society become even more unequal than it is now?" he asked. Tuljapurkar predicts that dramatic increases in lifespan will be confined to wealthy countries whose citizens can afford anti-aging technologies and whose governments can fund scientific research. This disparity further complicates current debates about healthcare accessibility, as the gap between rich and poor widens not only in quality of life but also increasingly in longevity.

"Big pharmaceutical companies have a consistent track record of being very strict when providing products to those who cannot pay," said Tuljapurkar.

If anti-aging technologies are distributed through an unregulated free market, "it's entirely possible we end up with a permanent global underclass—those nations locked into today’s mortality conditions," Tuljapurkar said. "If this happens, it creates negative feedback, a vicious cycle. Those excluded will remain permanently excluded."

Here is an equally strong statement from an article worrying about the consequences of human genetic enhancement:

Earlier this month, scientists announced they had edited genes in human embryos to remove a disease-causing mutation. This work is astonishing and answers prayers for many parents. Who wouldn’t want the chance to prevent their children from suffering pain that could now be avoided?

But this won't be the end. Many parents will seek genetic enhancements to give their children optimal advantages. Those with means will access these technologies. As capability arrives, ethical questions go beyond the ultimate safety of such technologies. The high cost of procedures will create scarcity and worsen already growing income inequality.

Similar viewpoints in other technological areas:

-

Digital technology overall: https://www.amnestyusa.org/issues/technology/technology-and-inequality/

-

Space travel: https://oilprice.com/Energy/Energy-General/What-Does-Billionaires-Dominating-Space-Travel-Mean-for-the-World.html

-

Solar geoengineering: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/global-sustainability/article/hidden-injustices-of-advancing-solar-geoengineering-research/F61C5DCBCA02E18F66CAC7E45CC76C57

This theme appears frequently in criticisms of new technologies. A related but fundamentally different theme is that technological products are used as tools for data collection, vendor lock-in, deliberate concealment of side effects (as modern vaccines have been criticized for), and other forms of abuse.

Emerging technologies often create more opportunities to obtain something without granting full rights or complete information about it, making older technologies appear safer from this perspective. This too represents how technology empowers elites at others' expense, but the issue here is the projection of power by manufacturers over users, rather than the access inequality seen in earlier examples.

I personally strongly support technology; if faced with a binary choice between “push forward” or “maintain status quo,” despite risks, I would gladly push forward almost everything except a few rare projects (such as gain-of-function research, weapons, and superintelligent AI).

This is because overall, the benefits include longer, healthier lives, more prosperous societies, maintaining greater human relevance amid rapid AI advancement, and preserving cultural continuity by having older generations live as living people rather than memories in history books.

But what if I put myself in the shoes of those less optimistic about positive impacts, or more worried about elites using new technologies to dominate economic rule and exert control—or both? For instance, I already feel this way about smart home products: the benefit of being able to talk to light bulbs is offset by my reluctance to let personal life flow to Google or Apple.

If I held more pessimistic assumptions, I could imagine feeling similarly about certain media technologies: if they allow elites to broadcast information more effectively than others, they could be used to exert control and drown out others. For many such technologies, the gains we get from better information or entertainment do not compensate for how they redistribute power.

Open Source as a Third Path

I believe one seriously underestimated idea in these situations is supporting only technologies developed via open source methods.

The argument that open source accelerates progress is highly credible: it makes it easier for people to build upon each other's innovations. At the same time, the argument that requiring open source slows progress is also highly credible: it prevents people from using many potentially profitable strategies.

But the most interesting consequences of open source are those unrelated to the speed of progress:

-

Open source improves access equality. If something is open source, it is naturally accessible to anyone in any country. For physical goods and services, people still need to pay marginal costs, but in many cases, proprietary product prices are inflated due to high fixed development costs discouraging competition—so marginal costs are often quite low, as in the pharmaceutical industry.

-

Open source improves equality in becoming a producer. One criticism is that giving people free end products doesn't help them acquire skills and experience needed to climb into prosperity within the global economy—the true reliable foundation for lasting high-quality life. Open source differs: it inherently enables anyone anywhere in the world to become a producer at every stage of the supply chain, not just a consumer.

-

Open source improves verifiability. If something is open source, ideally including not just outputs but also the process of invention, parameter choices, etc., it becomes easier to verify you’re getting what the provider claims, and for third parties to study and identify hidden flaws.

-

Open source eliminates opportunities for vendor lock-in. If something is open source, a manufacturer cannot remotely disable features or render it useless simply by going bankrupt—as highly computerized/connected cars may stop working after manufacturer shutdowns. You always retain the right to repair it yourself or request another provider.

We can analyze this from the perspective of some of the more radical technologies listed at the beginning of the article:

-

If we have proprietary life extension technology, it might be limited to billionaires and political leaders. Although personally I expect prices for such technology to drop quickly. But if it were open source, anyone could use it and offer it cheaply to others.

-

If we have proprietary human genetic enhancement technology, it might be limited to billionaires and political leaders, creating an upper class. Again, I personally think such technology would spread, but there would certainly be gaps between what the rich and ordinary people receive. But if it were open source, the gap between what well-connected elites receive versus others would be much smaller.

-

For biotechnology overall, an open-source scientific safety testing ecosystem might be more effective and honest than companies endorsing their own products backed by compliant regulators.

-

If only a few people can go to space, depending on politics, some might seize entire planets or moons. If the technology were more widely distributed, their chances of doing so would be smaller.

-

If smart cars are open source, you can verify manufacturers aren't spying on you, and you don't depend on the manufacturer to keep using your car.

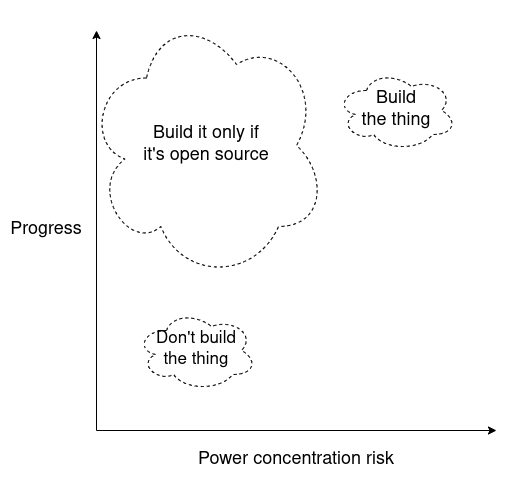

We can summarize the argument in a chart:

Note that the bubble for "build it only if open source" is wider, reflecting greater uncertainty about how much progress open source would bring and how much risk of power concentration it would prevent. Yet even so, on average, it remains a good deal in many cases.

Open Source and Misuse Risks

A major argument sometimes raised against open-sourcing powerful technologies is the risk of zero-sum behaviors and non-hierarchical forms of abuse. Giving everyone nuclear weapons would certainly end nuclear inequality. This is a real problem—we see multiple powerful states exploiting asymmetric nuclear access to bully others—but it would almost certainly result in billions dead.

As an example of negative social consequences without intentional harm, giving everyone access to plastic surgery could lead to zero-sum competition games, where everyone spends vast resources and even risks health trying to be more beautiful than others, yet ultimately society adjusts to higher beauty standards and isn't truly better off. Some forms of biotechnology might produce such effects at scale. Many technologies, including many biotechnologies, lie between these two extremes.

"I only support it if carefully controlled by trusted gatekeepers." This is a valid argument favoring the opposite direction. Gatekeepers could permit positive use cases while excluding negative ones. Gatekeepers could even be given public missions ensuring non-discriminatory access to everyone not violating certain rules.

However, I have strong default skepticism toward this approach. The main reason is I doubt whether truly trustworthy gatekeepers actually exist in the modern world. Many of the most zero-sum and highest-risk uses are military applications, and militaries have a poor historical record of self-restraint.

A good example is the Soviet biological weapons program:

Given Gorbachev’s restraint regarding SDI and nuclear weapons, his actions related to the Soviet illegal bacteriological weapons program are puzzling, Hoffman points out. When Gorbachev came to power in 1985, the USSR already had a broad biological weapons program initiated by Brezhnev, despite being a signatory to the Biological Weapons Convention. Beyond anthrax, the Soviets were researching smallpox, plague, and tularemia, though the intentions and targets of such weapons remained unclear.

"Kateyev’s documents show multiple Central Committee resolutions on biological warfare programs in the mid-to-late 1980s. It’s hard to believe all were signed and issued without Gorbachev’s knowledge," Hoffman says.

"There was even a May 1990 memo to Gorbachev about the biological weapons program—and that memo still doesn’t tell the whole story. The Soviet Union misled the world, and misled its own leadership."

The Russian Biological Weapons Program: Vanished or Disappeared? argues that after the Soviet collapse, the biological weapons program may have been transferred to other countries.

Other countries also have serious missteps needing explanation. I need not mention all nations involved in gain-of-function research and the associated implicit risks. In digital software fields like finance, histories of weaponized interdependence show that systems intended to prevent abuse easily slide into unilateral power projection by operators.

This is another weakness of gatekeepers: by default, they will be controlled by national governments whose political systems may have incentives to ensure domestic access equality, but no strong entity has a mission to ensure international access equality.

To clarify, I’m not saying gatekeepers are bad so let’s go full laissez-faire—at least not for gain-of-function research. Instead, I’m saying two things:

If something has enough "everyone-to-everyone abuse" risk that you’d only feel comfortable proceeding under centralized gatekeeper control in a closed system, consider whether the correct solution might be not doing it at all, and investing instead in alternative technologies with better risk profiles.

If something has enough "power dynamic" risk that you currently feel uncomfortable seeing it proceed at all, consider whether the correct solution is to do it—but do it openly, using open source methods, so everyone has a fair opportunity to understand and participate.

Also note that open source does not mean laissez-faire. For example, I support geoengineering conducted via open-source and open-science approaches. But this differs from "anyone can divert rivers and spray whatever they want into the atmosphere"—in practice, it wouldn’t lead to that: laws and international diplomacy exist, such actions are easily detectable, making any agreements reasonably enforceable.

The value of openness lies in ensuring democratization of technology—making it available to many nations rather than just one—and increasing information accessibility so people can more effectively form their own judgments about whether what’s being done is effective and safe.

Ultimately, I see open source as the strongest Schelling point for achieving technology with less risk of wealth, power concentration, and information asymmetry. Perhaps we can try building more sophisticated institutions to separate positive and negative effects of technology, but in the messy real world, the most likely durable approach is guaranteeing public right to know—that things happen openly, so anyone can understand what’s happening and participate.

In many cases, the immense value of accelerating technological development far outweighs these concerns. In a few cases, slowing technological development as much as possible is crucial until countermeasures or alternative ways to achieve the same goals become available.

Yet within existing frameworks of technological development, choosing open source as the method of advancement offers incremental improvement—a third option: less focused on the rate of progress, more on the style of progress, and using the expectation of openness as a lever to push developments in better directions—an underappreciated approach.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News