Private equity fundraising gains momentum, 4 crypto reserve companies may face downward stock pressure

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Private equity fundraising gains momentum, 4 crypto reserve companies may face downward stock pressure

Wait until sufficient liquidity and market price efficiency are established before entering; otherwise, you're playing a dangerous game suited only for institutions and hedge funds.

Author: Steven Ehrlich

Translation: TechFlow

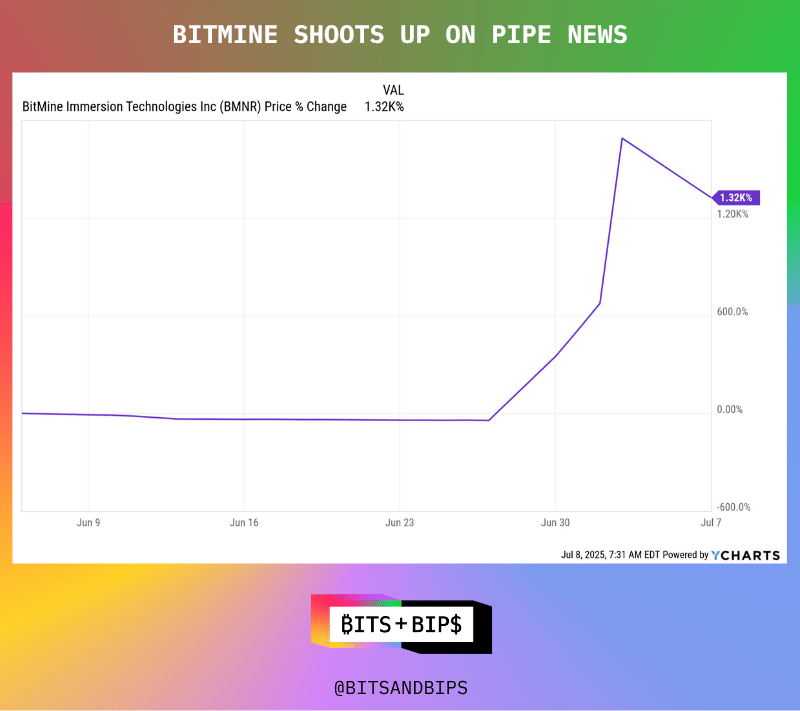

BitMine Immersion Technologies (BMNR), a Las Vegas-based bitcoin mining company, had a market capitalization of less than $30 million in June—modest for a competitive industry. But everything changed on June 25, when the company announced a strategic pivot toward an Ethereum-focused treasury strategy. As part of the transformation, the company raised $250 million through a private investment in public equity (PIPE) and appointed crypto bull Tom Lee as chairman of the board.

The stock immediately surged over 1300%. It now has a market cap of $4.6 billion and trades at 17.23 times book value.

(Yearly chart)

But this success story comes with significant caveats. Because Bitmine chose to raise funds via PIPE, a wave of selling pressure looms ahead. If history is any guide, the stock could fall by at least 60%—likely this summer—when shares sold to wealthy institutional clients during the $250 million financing become eligible for public resale.

How severe is this supply shock? Before the financing, Bitmine’s circulating supply was just 4.3 million shares. To raise $250 million, it had to issue an additional 55.56 million shares—an increase of 12.92x.

Bitmine isn’t alone in facing this challenge.

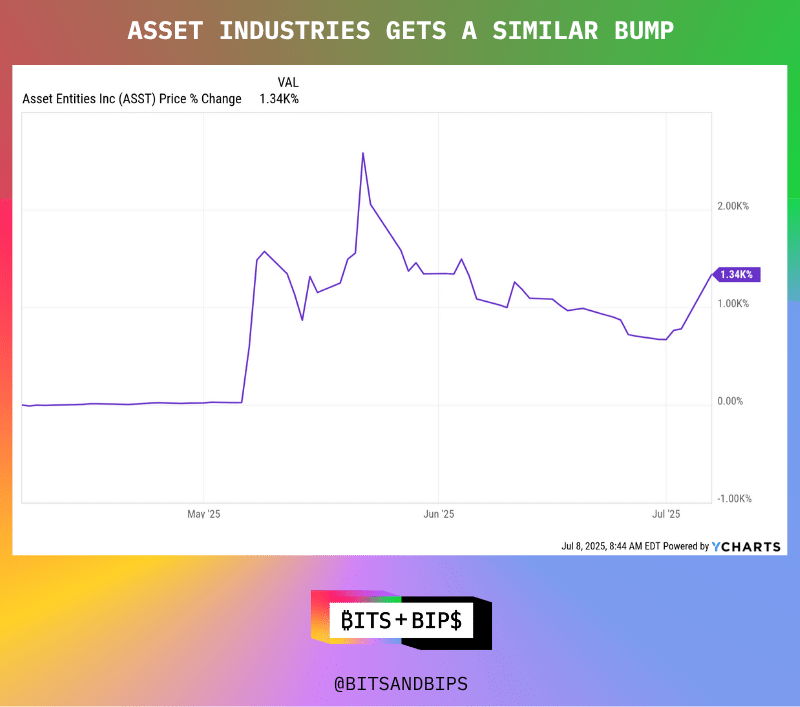

Asset Entities (ASST), a Dallas-based social media marketing firm, faces a similar situation. In early May, its market cap was under $10 million, with only 15.77 million shares outstanding. On May 27, that changed when the company raised $750 million via PIPE and merged with Strive Asset Management, led by former presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy. Its stock also soared more than 1300%.

(Yearly chart)

Like Bitmine, however, the company now faces massive selling pressure. The PIPE deal increased Asset Entity’s share count from 15.77 million to 361.81 million—a 21.94x increase.

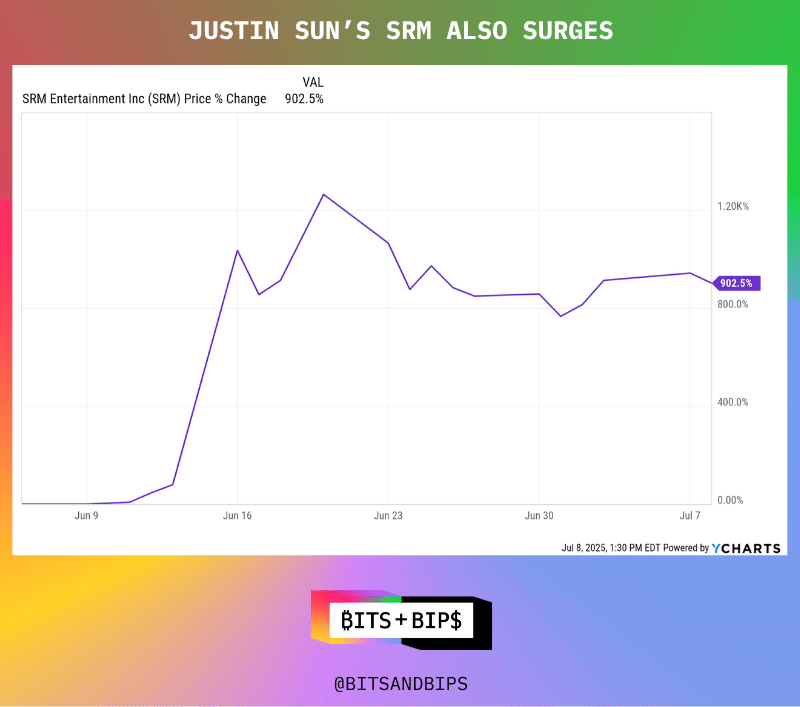

Justin Sun’s SRM Entertainment faces a similar fate. After agreeing to transform the memorabilia design firm into a Tron financial vehicle, its stock jumped 902.5%. As part of the $100 million PIPE financing, SRM expanded its original base of 17.24 million shares by 11.6x to accommodate 200 million newly issued shares.

(Yearly chart)

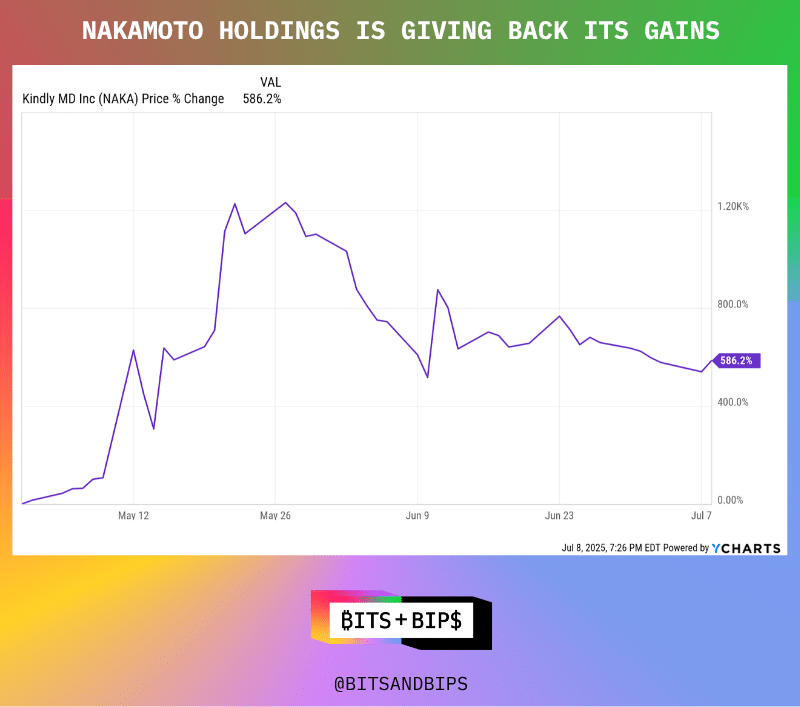

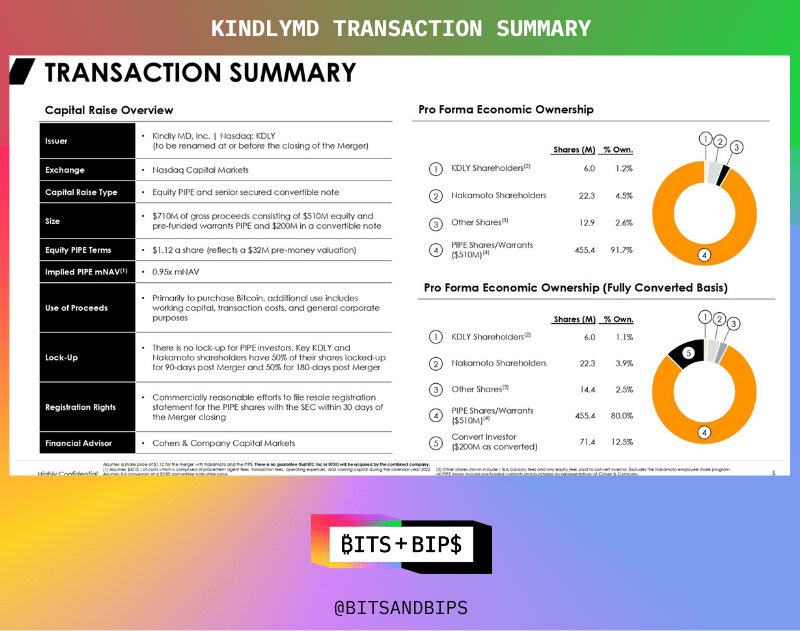

Finally, consider David Bailey of Bitcoin Magazine, who raised $563 million via PIPE to merge Nakamoto Holdings with KindlyMD (NAKA)—part of a broader $763 million funding round that included debt financing. On May 12, 2025, the merger was announced, increasing the share count 18.7x from 6.02 million to 112.6 million. The stock surged over 1200% after the announcement but later gave back half those gains—possibly because the deal hasn't closed yet and the company hasn’t started buying bitcoin in earnest. Still, it remains up 586.2% since the merger was first revealed.

(Yearly chart)

These companies exemplify the risks behind a new crypto trend: these treasuries are effectively leveraged hedge funds trading publicly. If investors aren’t careful, they could end up providing exit liquidity for institutions that got in at reasonable prices before the crypto rally began.

In fact, one investor involved in multiple such deals, speaking anonymously to Unchained, said: “It’s a tricky game. Most retail investors shouldn’t play. This is a game between institutions and hedge funds.”

The PIPE Financing Dream

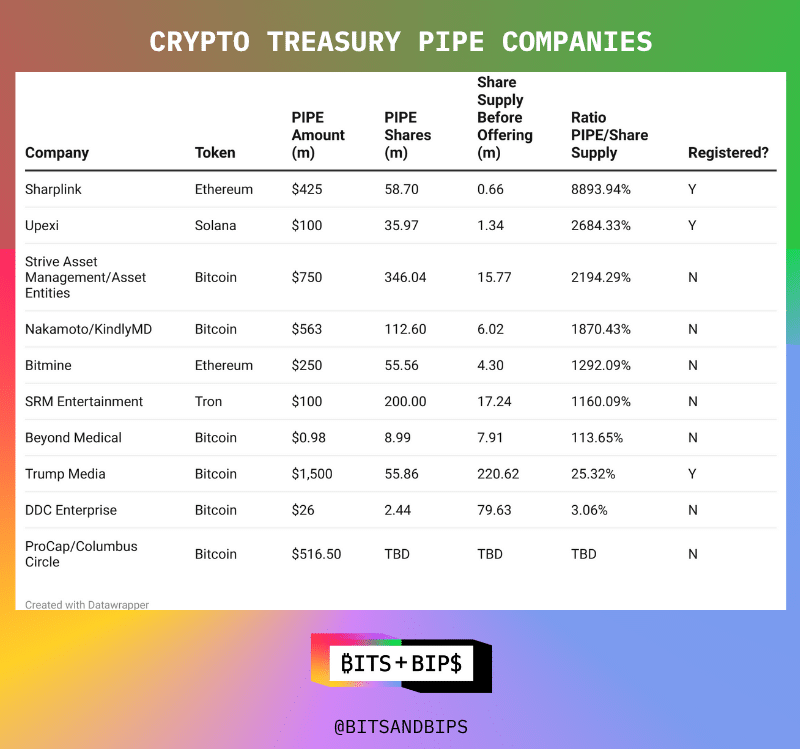

Not all such deals carry the same red flags as BitMine, Asset Entities, Nakamoto, or SRM. Several factors must be considered. Typically, participating companies resemble low-float, low-priced stocks—where float refers to the number of shares available for public trading. All four companies above fit this profile.

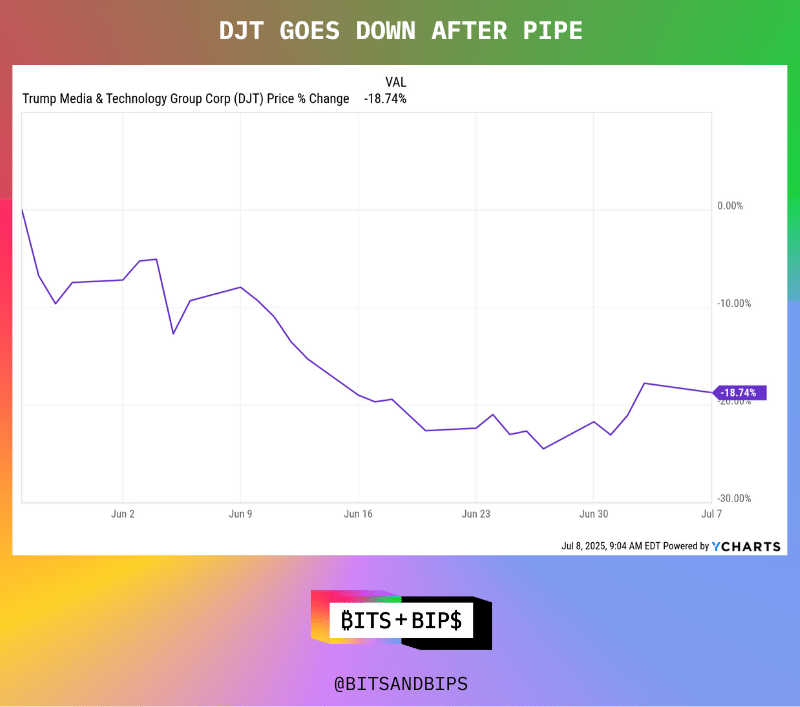

Then comes the PIPE transaction itself, which dramatically increases both numbers. As shown below, not all financings meet this threshold. For example, Trump Media Group (DJT) raised $1.5 billion via PIPE on May 27 (as part of a $2.5 billion deal including $1 billion in non-convertible debt), yet its stock barely moved—in fact, it declined. The 55.86 million newly issued shares represented only a 25.32% increase over its existing 220.62 million shares.

(Yearly chart)

(Company press release and SEC filings)

When these shares become sellable, timing becomes critical. Unlike IPO shares, PIPE shares aren’t immediately liquid because they’re not registered with the SEC. Registration involves filing a form—typically S-1 or S-3—with all material information investors need to make informed decisions: business outlook, use of proceeds, risk factors, etc.

For PIPE companies, especially U.S.-based ones (foreign firms have slightly different rules), the typical path is filing Form S-3, which is easier for existing public companies.

Most PIPE-funded companies promise investors they’ll file registration statements promptly. After all, who wants their assets locked up? Take the corporate presentation from Nakamoto/KindlyMD. In the slide below, the company commits to filing an S-3 “as soon as practicable” and notes there is no lock-up period for PIPE investors. However, it can’t file until the merger closes—expected this quarter.

(Nakamoto/KindlyMD)

Unfortunate Precedents in PIPE History

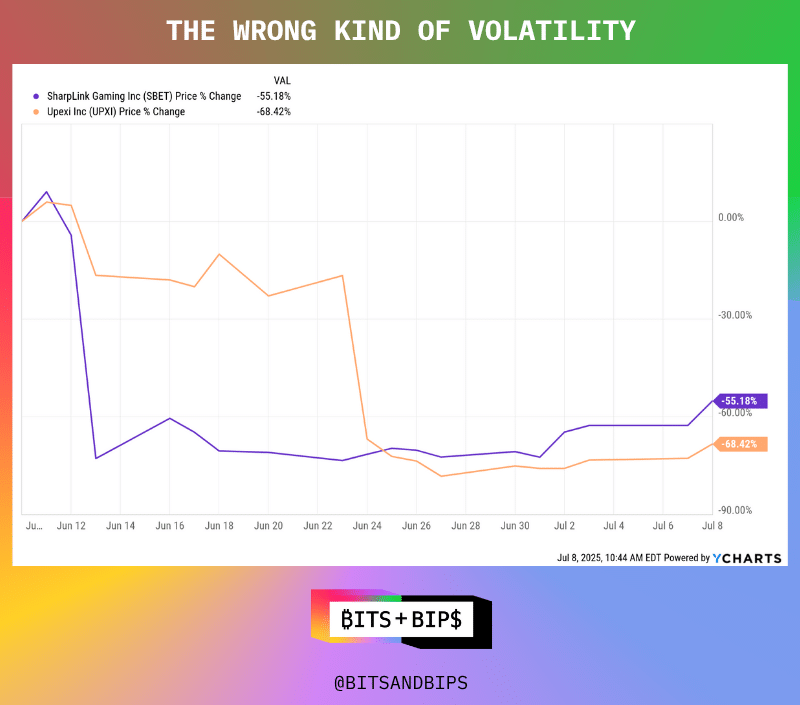

Two cautionary tales investors should know are Solana-focused Upexi (UPXI) and Ethereum-oriented Sharplink (SBET). Both raised large sums via PIPE and saw sharp post-registration declines.

(Yearly chart)

Sharplink raised $425 million, issuing 58.7 million new shares on top of its original 659,680—increasing supply by 8,893%. On June 12, it filed an S-ASR form, causing the stock to plummet. S-ASR is a variant of S-3 registration—but because the company is a well-known seasoned issuer (WKSI), the shares can be sold immediately, enabling private placements like PIPE.

A similar story unfolded at Upexi, a former real estate tech firm repositioned this spring as a Solana financial company. It raised $100 million via PIPE, increasing its float from 1.34 million to 35.97 million shares—a 25.69x jump. Its S-1 registration became effective on June 23, and the price drop in the chart above clearly reflects that.

Sharplink executives didn’t respond to interview requests about the price drop, but Upexi arranged for its new chief strategy officer, Brian Rudick, to speak. Asked if he expected such a decline post-effectiveness, he acknowledged it was always possible. “When we went out to raise the PIPE, we weren’t sure whether everyone would hold or whether the market would worry about potential selling [from nearly 15 crypto VCs in the PIPE],” Rudick said. “We knew selling was always a possibility. But to get into the market quickly, I think it was a trade-off we were clearly willing to make.”

In fact, such selling may be necessary to inject sufficient liquidity for true price discovery.

What Treasury Companies and Investors Can Do

Given the precedents of Sharplink and Upexi, Bitmine, Asset Entities, and SRM seem destined for a similar transition—and appear powerless to stop it.

A lawyer familiar with such transactions, speaking anonymously to Unchained, said: “You *can* [make agreements restricting sales]. I think you do it to avoid appearances. Some might say, ‘We weren’t going to sell anyway, so agreeing to a lock-up won’t hurt,’ and maybe on the surface, it reassures people. But when you have a large group like this, management gets complicated. Will anyone actually do it? I doubt it. But if it reassures the market, maybe you can.”

Perhaps the next best hope is that investors hold these stocks long enough to qualify for favorable capital gains tax treatment instead of ordinary income tax. One Upexi and Sharplink investor, who asked to remain anonymous and claimed not to have sold either position, explained his thinking: “From a tax perspective, constant buying and selling is inefficient. You just lose to short-term capital gains—paying 40% tax. If you’re directionally long and believe the net asset value premium will roughly stay where it is, you might save 20% in taxes.”

But this theory has two problems. First, if investors think others might start selling, they may panic and sell too. In other words, they might not want to be first—but wouldn’t mind being second. Second, if a company built a large position based on a previously tiny float, it doesn’t take mass selling to crush the stock price.

Perhaps the best solution is diversifying funding sources when issuing these securities. Each approach has pros and cons. PIPE offers a simple way to raise large amounts quickly—helpful for launching accumulation strategies—but risks creating massive overhang. Issuers could try alternative methods, like pre-registering shares with the SEC, though that takes longer to secure needed capital. Increasingly, companies are adopting hybrid models—raising one-third via PIPE and the rest through convertible bonds or credit facilities. These delay selling pressure but add leverage to the balance sheet, which could backfire if the stock crashes.

Yet in a size-at-all-costs world, companies often feel pressured to raise capital fast—meaning full commitment to PIPE. Markets will likely remain in a “Wild West” state, so investors should heed institutional advice: “Wait until liquidity is sufficient before buying. Don’t speculate on how much the premium over NAV will expand. Wait for full liquidity and efficient market pricing.”

Representatives from Sharplink, Bitmine, Asset Entities, Nakamoto/KindlyMD, and SRM Entertainment either did not respond to inquiries or declined interviews.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News