Delphi Digital researcher: If building chains is creating assets, which on-chain products have potential?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Delphi Digital researcher: If building chains is creating assets, which on-chain products have potential?

Blockchain adoption is just a matter of time by providing clear structural advantages across five areas: tokenization, DeVin, DePin, payments, and speculation.

Author: Robbie Petersen

Translation: TechFlow

At its core, a blockchain is a ledger of assets. This suggests it excels in three key areas:

-

Issuing assets

-

Transferring assets

-

Programming assets

Objectively speaking, any cryptocurrency use case that leverages these capabilities gains structural advantages from operating on-chain. Conversely, use cases that fail to leverage them do not gain such advantages. In most cases, their appeal stems more from ideological alignment than functional unlocks.

While decentralization, privacy, and censorship resistance are undoubtedly worthy goals, these traits effectively limit the total addressable market (TAM) of programmable asset ledgers to a niche group of idealists. It’s becoming increasingly clear that mass adoption will be driven by pragmatism, not pure idealism. Therefore, this article focuses on applications that become inferior products without blockchain:

-

Asset tokenization

-

Decentralized Virtual Infrastructure Networks (DeVin)

-

Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Networks (DePin)

-

Stablecoins and payments

-

Speculation

Before diving in, two points are worth emphasizing:

First, the following arguments are derived from first principles. This means we aren’t simply forcing crypto solutions onto problems, but instead identifying persistent problems that exist regardless of crypto, then assessing whether crypto offers a structurally superior solution.

Second, this article strives for nuance. As humans, our brains naturally simplify complexity and favor simple-sounding answers. But reality isn't simple—it's full of subtleties.

Argument One: Asset Tokenization

Financial assets generally fall into two categories:

-

Securitized assets

-

Non-securitized assets

While this distinction may seem trivial, it’s crucial for understanding how traditional financial ledgers operate. Securitized assets have two defining characteristics compared to non-securitized ones:

First, they all have a CUSIP—a unique 9-character alphanumeric code used to identify financial instruments like stocks, bonds, and other securities. For example, Apple’s common stock has the CUSIP 037833100. CUSIPs are used in North America; elsewhere, ISINs (International Securities Identification Numbers) are used—12-digit codes that contain the CUSIP. These codes establish trust through standardization. As long as an asset has a CUSIP, all parties can operate under the same framework.

The second notable feature is that securitized assets almost always settle through a central clearinghouse. In the U.S. (and to some extent globally), that institution is the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC). DTCC and its subsidiaries ensure trades are properly cleared and settled.

For instance, when you buy 10 shares of Tesla on Robinhood, your trade goes to an exchange or market maker and gets matched with a seller. Then DTCC’s National Securities Clearing Corporation (NSCC) steps in to clear the trade, ensuring both parties fulfill their obligations. Finally, DTCC’s Depository Trust Company (DTC) settles the transaction on T+1—transferring $2,500 to the seller and moving the 10 Tesla shares into Robinhood’s DTC account. By the next day, your Robinhood app shows ownership of those shares.

When people say blockchain can replace existing financial infrastructure and enable faster, cheaper settlement, they usually mean replacing DTCC and its closed, centralized ledger. While blockchains offer structural advantages due to openness and programmability—such as eliminating batch processing, removing T+1 delays, improving capital efficiency, and embedding compliance—they face three major hurdles in displacing DTCC:

-

Path dependency: Existing securities standards (like CUSIP/ISIN) and the bilateral network effects created by DTCC as the authoritative settlement layer make replacing the current system nearly impossible. The switching cost for DTCC is extremely high.

-

Structural incentives: DTCC is a highly regulated clearinghouse owned by its users—the major financial institutions in the securities industry, including banks, brokers, and dealers (e.g., JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs). In other words, the very entities that would need to collectively agree on a new settlement system also have vested interests in maintaining the status quo.

-

Complexity of T+1 settlement: Similar to payments (discussed later), T+1 exists not just because infrastructure is outdated, but for practical reasons. Brokers don’t always have sufficient liquidity to settle orders instantly. A one-day buffer allows time to raise funds via loans or bank transfers. Second, DTCC’s netting process reduces the number of transactions needing execution. For example, 1,000 Tesla buy orders and 800 sell orders can be netted down to 200. Intuitively, longer time windows increase netting efficiency. Instant settlement would dramatically increase transaction volume—something no current blockchain could handle. For reference, DTCC processed $25 quadrillion in transaction volume in 2023.

In short, rather than being replaced by blockchain, DTCC is more likely to upgrade its own systems. This implies that any securities traded on-chain are essentially secondary issuances—they still require back-end settlement via DTCC. This undermines any theoretical structural advantage offered by blockchain while adding extra costs and complexity to tokenization, such as relying on oracles to sync price data.

Thus, the value proposition of on-chain securities is reduced to a less compelling feature: regulatory arbitrage, enabling access to securities for entities without KYC (Know Your Customer) clearance. While demand exists—especially in emerging markets—it represents only a small fraction of the primary issuance market.

This doesn’t mean blockchain has no role in securities tokenization. While domestic clearinghouses currently function “well enough” and won’t be disrupted due to structural reasons, global interoperability between clearinghouses remains suboptimal (settlement often takes T+3). Blockchain could serve as a unified coordination layer between global clearing institutions, leveraging its borderless, open ledger to reduce international settlement times from T+3 to near-zero. More intriguingly, this could provide a strong foothold to gradually erode domestic settlement markets without facing cold-start problems. As we’ll discuss further in the context of payments, this logic appears equally applicable.

Unlocking Long-Tail Liquidity

Now consider the second category: non-securitized assets. By definition, these lack a CUSIP and don’t rely on DTCC or traditional financial infrastructure. Most are bought and sold bilaterally—or not traded at all. Examples include private credit, real estate, trade finance receivables, intellectual property, collectibles, and fund shares (private equity, venture capital, hedge funds).

These assets remain unsecuritized for several reasons:

1. Asset Heterogeneity

Securitization requires homogeneity to enable packaging and standardization. However, these assets are largely heterogeneous—each property, private loan, receivable, fund share, or artwork has unique characteristics, making aggregation and standardization difficult.

2. Lack of Active Secondary Markets

There’s no authoritative secondary market like the NYSE to connect buyers and sellers. Even if these assets were securitized and settled via DTCC, there would be no exchange to facilitate trading.

3. High Entry Barriers

The securitization process typically takes over six months and costs issuers more than $2 million. While some steps ensure compliance and trust, the entire process is overly lengthy and expensive.

Returning to the article’s central thesis, as a programmable asset ledger, blockchain excels in three areas—all of which directly address these pain points:

-

Asset Issuance

-

While securitization has high barriers, tokenizing these assets on-chain faces far less friction. Moreover, this doesn’t necessarily sacrifice regulatory compliance, as compliance logic can be embedded directly into the asset.

-

Asset Transfer

-

Blockchain provides backend infrastructure—a shared asset ledger—for building unified liquidity markets. Other markets (e.g., lending, derivatives) can be built atop this foundation, enhancing efficiency.

-

Asset Programming

-

DTCC still runs on decades-old systems, including COBOL, while blockchain enables direct embedding of logic into assets. This means complex logic can be encoded into tokens, simplifying or bundling heterogeneous assets into tradable forms.

In short, while blockchain may offer only marginal improvements to existing securities markets (like DTCC), it brings transformative change to non-securitized assets. This suggests the rational adoption path for programmable asset ledgers may begin with long-tail assets—an intuitive trajectory that aligns with patterns seen in most emerging technologies.

The MBS Moment

A somewhat unconventional view I hold is that mortgage-backed securities (MBS) were one of the most important technologies of the past 50 years. By transforming mortgages into standardized securities tradable on liquid secondary markets, MBS improved price discovery through a more competitive investor pool and reduced the historical illiquidity premium embedded in mortgage financing. In other words, we can finance housing at significantly lower costs thanks to MBS.

Over the next five years, I expect nearly every illiquid asset class to experience its “MBS moment.” Tokenization will bring more liquid secondary markets, fiercer competition, better price discovery, and most importantly, more efficient capital allocation.

Argument Two: Decentralized Virtual Infrastructure Networks (DeVin)

Artificial intelligence (AI) will surpass human intelligence across nearly every domain in human history—and it will do so for the first time. More importantly, this intelligence won’t stagnate—it will continuously improve, specialize, collaborate, and scale almost infinitely. Put differently, imagine infinitely replicating the most effective individual in every field (limited only by compute), hyper-optimizing them, and enabling seamless collaboration. The impact would be immense.

In short, AI’s impact will be enormous—even greater than our linear thinking can intuitively grasp.

This naturally raises a question: Will blockchain, as a programmable asset ledger, play a role in this emerging agentic economy?

I believe blockchain will enhance AI capabilities in two ways:

-

Resource coordination

-

Economic foundation for agent transactions

In this article, we’ll focus on the first use case. If you’re interested in the second, I wrote about it previously (in short: blockchain could become the foundation of the agentic economy, but it will take time).

The Commodities of the Future

Fundamentally, AI—especially autonomous agents—requires five core inputs to function:

-

Energy: Electricity powers AI hardware. Without energy, there’s no compute, and thus no AI.

-

Compute: Processing power drives AI inference and learning. Without compute, AI cannot process inputs or perform functions.

-

Bandwidth: Data transmission capacity supports AI connectivity. Without bandwidth, agents can’t collaborate or update in real time.

-

Storage: Capacity to store AI data and software. Without storage, AI cannot retain knowledge or state.

-

Data: Context for AI to learn and respond.

In this article, we’ll focus on the first four. To understand a compelling blockchain application in the context of AI, we must first examine how compute, energy, bandwidth, and storage are currently procured and priced.

Unlike traditional commodity markets that adjust prices dynamically based on supply and demand, these markets typically operate via rigid bilateral agreements. For example: compute is primarily sourced through long-term cloud contracts with giants like AWS or by directly purchasing GPUs from Nvidia. Energy procurement is similarly inefficient—data centers typically sign fixed-price Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) with utilities or wholesale energy providers, often years in advance. Storage and bandwidth markets exhibit similar structural inefficiencies: storage is usually purchased in predetermined blocks from cloud providers, leading companies to over-provision to avoid capacity shortages. Similarly, bandwidth is obtained through rigid agreements with ISPs and CDNs, forcing companies to prioritize peak demand over average utilization.

The common flaw across these markets is the lack of fine-grained, real-time price discovery. By selling resources through rigid tiered pricing instead of continuous price curves, existing systems sacrifice efficiency for predictability, resulting in poor coordination between buyers and sellers. This typically leads to two outcomes: 1. Resource waste. 2. Companies constrained by resource limits. Ultimately, suboptimal resource allocation prevails.

Programmable asset ledgers offer a compelling solution. Although these resources may never be securitized for the reasons mentioned earlier, they can still be easily tokenized. By establishing tokenized bases for compute, energy, storage, and bandwidth, blockchain could theoretically unlock liquid markets and real-time dynamic pricing.

Critically, this is something traditional ledgers cannot achieve. As programmable asset ledgers, blockchains offer five structural advantages in this context:

-

Real-time Settlement

-

If an asset ledger takes days or even hours to settle resource exchanges, it undermines market efficiency. Blockchain, due to its openness, borderlessness, 24/7 operation, and real-time nature, ensures markets aren’t delayed.

-

Openness

-

Unlike traditional resource markets dominated by oligopolies, blockchain-based markets have low entry barriers on the supply side. An open market allows any infrastructure provider—from hyperscalers to small operators—to tokenize and offer excess capacity. Contrary to popular belief, long-tail players dominate data center capacity.

-

Composability

-

Blockchain enables derivative markets to be built atop these, promoting higher efficiency. Buyers and sellers can hedge risks like in traditional commodity markets.

-

Programmability

-

Smart contracts allow complex conditional logic to be embedded directly into resource allocation. For example, compute tokens could automatically adjust execution priority based on network congestion, or storage tokens could replicate data across regions to optimize latency and redundancy.

-

Transparency

-

On-chain markets provide visibility into pricing trends and utilization patterns, enabling participants to make better decisions and reducing information asymmetry.

While this idea might have faced skepticism years ago, the rapid rise of autonomous AI agents will accelerate demand for tokenized resource markets. As agents proliferate, they will inherently require dynamic access to these resources.

For example, imagine an autonomous video-processing agent analyzing security footage from thousands of locations. Its daily compute needs could fluctuate by orders of magnitude—requiring minimal resources during normal activity but potentially thousands of GPU hours during anomaly events for deep analysis of multiple streams. Under traditional cloud models, this agent would either waste vast resources through over-provisioning or face critical performance bottlenecks during peak demand.

With a tokenized compute market, however, the agent could programmatically acquire resources on-demand at market-clearing prices. When an anomaly is detected, it could immediately bid for and obtain additional compute tokens, process footage at maximum speed, then release those resources back to the market upon completion—all without human intervention. Multiply this economic efficiency across millions of autonomous agents, and the improvement in resource allocation becomes incomparable to traditional procurement models.

More intriguingly, this could enable entirely new applications previously deemed impossible. Today’s agents still rely on organized corporations that pre-provision compute, energy, storage, and bandwidth. With blockchain-powered markets, agents could autonomously acquire these critical resources as needed. This flips the model—agents become independent economic actors.

This, in turn, could fuel greater specialization and experimentation, as agents optimize for increasingly narrow use cases without institutional constraints. The end result is a fundamentally different paradigm—breakthrough AI applications no longer emerge top-down, but from autonomous interactions among agents. All made possible by the unique capabilities of programmable asset ledgers.

Looking Ahead

This shift may initially be slow and gradual, but as agents grow in autonomy and economic significance, the structural advantages of on-chain resource markets will become increasingly evident.

Just as yesterday’s commodities—oil, agriculture, metals, land—eventually formed efficient markets, tomorrow’s commodities—compute, energy, bandwidth, storage—will inevitably find theirs. And this time, they’ll be built on blockchain.

Argument Three: Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Networks (DePin)

In the previous argument, we explored how programmable asset ledgers can serve as the digital foundation for emerging resource markets. Here, we examine how blockchain can simultaneously disrupt the operation of physical infrastructure. While we won’t dive into every vertical (my research with @PonderingDurian covers this extensively), the following logic applies to any DePin sector (e.g., telecom, GPUs, location, energy, storage, data).

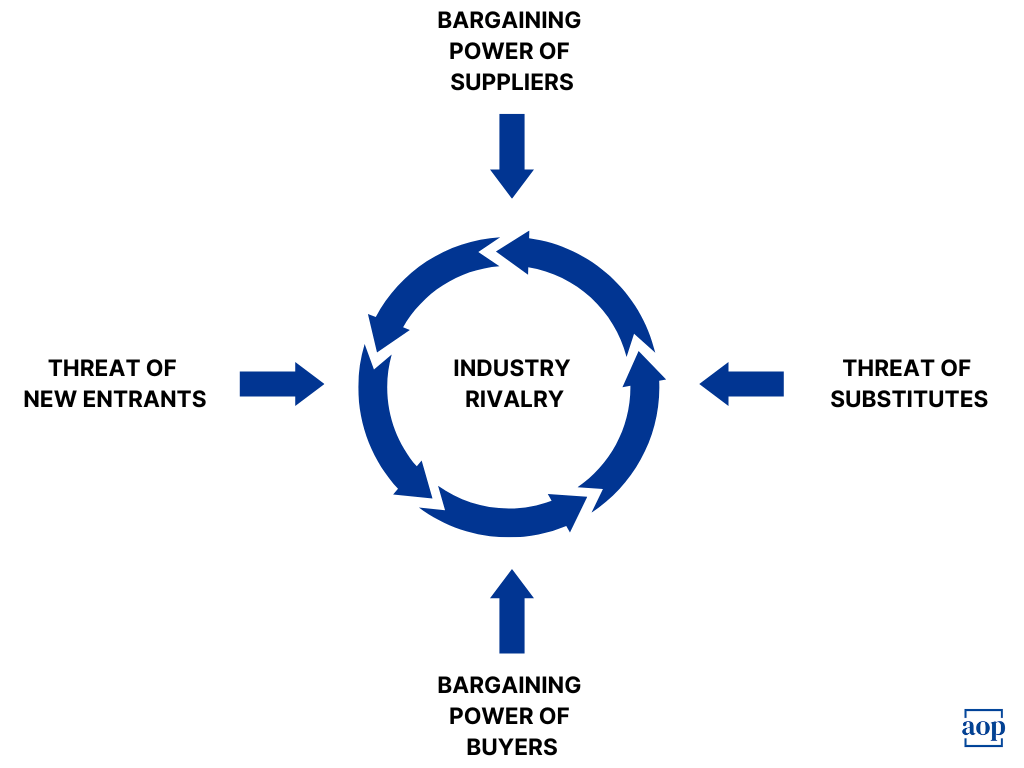

Porter’s Five Forces Model

To understand the economics of physical infrastructure firms and how blockchain and DePin models might disrupt them, one of the best frameworks is Michael Porter’s “Five Forces Model.”

Porter’s framework specifically outlines the forces that erode profit margins in the absence of structural moats. The five competitive forces are:

-

Rivalry Among Existing Competitors

-

Is there intense competition within the industry that could trigger price wars? Infrastructure giants typically operate as cooperative oligopolies, implicitly or explicitly maintaining high prices to preserve healthy margins.

-

Threat of New Entrants

-

How easy is it for new competitors to enter the market? High capital intensity and economies of scale protect infrastructure giants from new entrants.

-

Threat of Substitutes

-

Do substitute products undermine the value of existing offerings? Since infrastructure businesses are inherently commoditized, they typically don’t face threats from substitutes.

-

Bargaining Power of Buyers

-

A firm’s pricing power is key to profitability. Can buyers (customers or enterprises) demand lower prices or better terms, squeezing supplier profits? Infrastructure giants usually face low switching costs, meaning in commodity markets, the lowest-cost producers tend to win.

-

Bargaining Power of Suppliers

-

A firm’s input costs form the denominator of its profit equation. Can the firm influence suppliers of key inputs to keep costs moderate? The three main inputs for infrastructure giants are: (1) land, (2) labor, and (3) hardware. While suppliers do have some bargaining power, large firms typically mitigate risks through fixed contracts and bulk purchasing.

Clearly, this framework shows physical infrastructure giants are highly defensible businesses—a fact consistent with their sustained market positions over the past 30 years. Yet DePin emerges as a powerful challenger, capable of disrupting these giants for three structural reasons.

DePIN’s Structural Advantages

First, DePin leverages a novel capital formation model—outsourcing upfront network-building costs to individual contributors. In return, contributors receive tokens representing future network growth. This enables DePin projects to reach critical scale with competitive unit economics without initial centralized fundraising. More importantly, this suggests DePin can cultivate viable new entrants by breaking the economies of scale that protect incumbent firms.

Second, DePin fundamentally improves the fifth force in Porter’s model: supplier bargaining power. By leveraging a distributed network of individuals, DePin bypasses two (if not all three) of the major input costs for physical infrastructure:

-

Land: By tapping contributors who already own land, DePin eliminates this cost entirely.

-

Labor: Similarly, DePin outsources node setup and maintenance to network participants, avoiding labor costs.

The third structural advantage of DePin is finer supply-demand matching, reducing deadweight loss. This is especially evident in geographically dependent networks (e.g., DeWi). These projects can first identify areas with highest bandwidth demand and concentrate token incentives there. If demand spikes elsewhere, they can dynamically adjust incentives. This contrasts sharply with traditional infrastructure firms, which often build supply hoping demand follows. If demand drops, telecoms still bear infrastructure maintenance costs, creating deadweight loss. Decentralized DePin networks can match supply and demand more precisely.

Looking Ahead

Going forward, I expect DePin to shine in two key demand-side areas:

-

B2B Applications: Enterprises are highly cost-sensitive (e.g., compute, data, location, storage).

-

Consumer Goods: Consumers have no strong brand preferences and mainly optimize for cost (e.g., bandwidth, energy).

Argument Four: Stablecoins and Global Payments

In 2023, global GDP was around $100 trillion. That year, global transaction fee spending exceeded $2 trillion. In other words, $2 of every $100 spent went toward transaction fees. As the world continues to break geographical barriers, this figure is expected to grow steadily at a 7% CAGR. Against this backdrop, reducing global payment costs is clearly a massive opportunity.

Like domestic payments, high cross-border transaction fees stem not from network infrastructure, but from risk management. Contrary to popular belief, the messaging layer enabling global payments—SWIFT—is actually very cheap (@sytaylor). SWIFT network fees are typically $0.05–$0.20 per transaction. The remaining cost—often $40–$120—comes from two sources:

-

Risk and Compliance: Banks are required by regulators to ensure cross-border transactions comply with KYC (Know Your Customer), AML (Anti-Money Laundering), sanctions, and other monetary restrictions. Violations can lead to fines up to $9 billion. Thus, banks handling cross-border payments must invest heavily in dedicated teams and infrastructure to avoid accidental breaches.

-

Correspondent Banking Relationships: To move money globally, banks must maintain correspondent relationships with other banks. Differences in jurisdictional risk and compliance policies create reconciliation overhead. Specialized teams and systems are needed to manage these relationships.

Ultimately, these costs are passed to end users. Therefore, merely stating “we need cheaper global payments” misses the point. What’s truly needed is a structurally superior way to audit and manage the risks inherent in global payments.

Intuitively, this is where blockchain excels. Blockchain not only bypasses reliance on correspondent banks but also provides an open ledger where all transactions are auditable in real time—offering a fundamentally superior asset ledger for risk management.

Even more interestingly, blockchain’s programmability allows necessary payment rules or compliance requirements to be embedded directly into transactions. Programmability also enables staking yields from stablecoin reserves to be distributed to participants in cross-border payments (possibly even end users). This contrasts sharply with traditional remittance services like Western Union, whose funds sit idle in global prepaid accounts, unable to be productively deployed.

The net effect is that underwriting risk costs are compressed to the cost of programming an open ledger to handle compliance and risk management (plus on/off-ramp costs if needed), minus the yield generated from staked stablecoin assets. This presents a significant structural advantage over existing correspondent banking solutions and modern cross-border payment platforms reliant on closed, centralized databases (e.g., Wise).

Perhaps most importantly, unlike domestic payments, governments appear to have little incentive to build globally interoperable payment infrastructure—this would undermine the value proposition of stablecoins. In fact, I believe governments have strong structural incentives *not* to build interoperable payment rails, ensuring value remains concentrated in domestic currencies.

This may be one of stablecoins’ greatest tailwinds—cross-border payments represent a unique public market failure, and the solution must come from the private sector. As long as governments have structural incentives to maintain inefficient global payment infrastructure, stablecoins will remain well-positioned to facilitate global commerce and capture a share of the over $2 trillion in annual cross-border transaction fees.

Stablecoin Adoption Pathways

Finally, we can speculate on stablecoin adoption trajectories. Stablecoin adoption will ultimately depend on two key vectors:

-

Payment Type (e.g., B2B, B2C, C2C)

-

Payment Corridor (e.g., G7, G20 emerging nations, long-tail markets)

Intuitively, corridors with the highest payment fees and weakest banking/payment infrastructure will adopt stablecoins first (e.g., Global South, Latin America, Southeast Asia). These regions are also often hardest hit by irresponsible monetary policy and historically volatile local currencies. In these areas, stablecoin adoption offers not only lower transaction costs but also access to the U.S. dollar. The latter is arguably the biggest driver of current stablecoin demand in these regions—and likely will remain so.

Second, since enterprises are more cost-sensitive than consumers, B2B use cases will lead adoption along these vectors. Today, over 90% of cross-border payments are B2B. Within this segment, small and medium businesses (SMBs) appear best positioned to adopt stablecoins—due to thinner margins and greater willingness to accept higher risk than large enterprises. SMBs that lack access to traditional banking infrastructure but need dollar exposure represent a prime entry point. Other significant stablecoin use cases in global contexts include treasury management, trade finance, international payouts, and receivables.

Looking ahead, as long-tail markets gradually adopt stablecoins as a structurally superior cross-border payment method, other markets will follow, as these advantages become too pronounced to ignore.

Argument Five: Speculation

The final argument may be the most obvious and direct. Humans have an innate desire to speculate and gamble. This desire has existed for millennia and will only persist into the future.

Moreover, it’s increasingly clear that blockchain holds unique advantages in fulfilling this need. As a programmable asset ledger, blockchain once again lowers the barrier to issuing assets—here, speculative assets with nonlinear payoffs. This includes everything from perpetuals (perps) to prediction markets to memecoins.

Looking ahead, as users explore the risk curve and seek increasingly nonlinear outcomes, blockchain appears poised to meet this demand through ever more novel forms of speculation. This could include markets for athletes, musicians, songs, social trends, or even specific TikTok posts.

Humans will continue to seek new ways to speculate, and blockchain is the principled, optimal solution to serve this demand.

Looking Ahead

Historically, technology adoption follows a similar trajectory:

-

An emerging technology offers structural advantages;

-

A small set of firms adopt it to improve margins;

-

Incumbents either follow suit to stay competitive or lose market share;

-

Capitalism naturally selects winners, and the new technology becomes standard.

In my view, this is why blockchain adoption as a programmable asset ledger is not only possible—but inevitable. By offering clear structural advantages across five domains (tokenization, DeVin, DePin, payments, and speculation), blockchain adoption is merely a matter of time. While the exact timeline remains unclear, one thing is certain: we’ve never been closer.

Lastly, if you're building something at the frontier of these fields, feel free to DM me!

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News