The Political Passion of the Trump Era: After Destruction, Where Is Reconstruction?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Political Passion of the Trump Era: After Destruction, Where Is Reconstruction?

Simply smashing the old order does not create anything.

By Noah Smith

Translated by Block unicorn

"Men don't care what's on TV. They only care what else is on." — Jerry Seinfeld

N.S. Lyons is a popular essayist within the "national conservative" tradition. His Substack, The Upheaval, is worth reading, even though I disagree with less than half of what he writes. He is widely read, deeply informed, capable of synthesizing insights from multiple domains, and unafraid to think through major historical questions in real time. Reading him helps you understand the modern right’s worldview. On many issues, his message is exactly what people in the MAGA world urgently need to hear.

In a recent piece titled The God of Power for America, Lyons articulates what I believe is a profound truth about our current historical moment. He argues that the “long twentieth century” has ended—that era defined by liberalism (social, political, and economic) and anchored in the rejection of Adolf Hitler:

I believe what we are witnessing today is indeed the end of an age, a tectonic disruption of the world as we’ve known it—and the full weight and implications of this transformation have yet to truly reach us.

More specifically, I see Donald Trump as marking the long-delayed conclusion of the “long twentieth century”...

Our “long twentieth century” started late, only fully consolidated in 1945, but for the next 80 years its spirit dominated our civilization’s understanding of how the world was and ought to be... In the wake of the horrors of World War II, American and European elites rightly made “never again” the core of their ideological framework. They resolved together never to allow fascism, war, and genocide to threaten humanity once more...

Anti-fascism of the twentieth century evolved into a great crusade... By placing “never again” as the ultimate priority, the ideology of the open society placed the summum malum (the greatest evil) at its center, rather than the summum bonum (the highest good). The singular figure of Adolf Hitler not only lurked deep in the mind of the twentieth-century person; he ruled the subconscious as a secular Satan... As Rémi Brague quipped, this “second career of Adolf Hitler” provided the open society consensus and the entire postwar liberal order with a quasi-religious raison d'être: preventing the resurrection of the undead Führer...

The “long twentieth century” was characterized by three interrelated postwar projects: the gradual opening of society through the deconstruction of norms and boundaries, the consolidation of the managerial state, and the hegemony of the liberal international order. It was hoped that these three projects would jointly lay the foundation for a world of lasting peace and universal human fellowship.

Like all strong essays, this one exaggerates somewhat. Postwar American-led liberalism was not purely defensive. The motivations behind the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights were not fear of Hitler’s return, but a desire to extend the frontiers of human freedom and dignity further than ever before. Ronald Reagan didn’t need Hitler as a bogeyman to promote his vision of American liberty—he saw it as a universal ideal.

Yet Lyons is importantly correct. The staggering horror and catastrophic failure of the Nazi regime provided liberals with a moral anchor—a benchmark against which they could always justify further liberalization. Advocates of civil rights acts and other liberalizing laws in the U.S. and Europe routinely invoked Nazi Germany as a rhetorical foil. Anti-communism once offered the right another Satan, but it never carried quite the same weight, given America’s wartime alliance with Stalin; after the Soviet collapse, anti-communism quickly faded, but Hitler and the Nazis did not.

Lyons is right that the Trump era marks the end of Hitler as the West’s cultural embodiment of absolute evil—at least in the United States. The two most popular media figures on the American right, Joe Rogan and Tucker Carlson, have invited Darryl Cooper—a historical revisionist who downplays Nazi atrocities and casts Winston Churchill as the true villain of WWII—onto their shows. For reference, here is one of Cooper’s (now-deleted) tweets:

This tweet, I believe, illustrates the mindset of the American right. It’s wrong to claim that the Trump movement or modern national conservatism represents full-throated support for Nazism. But there is no doubt that the American right sees “wokeness” as a greater threat than the possible return of Hitler.

Why has the legend of Hitler lost its terror? Several reasons. The generation that defeated the Nazis has mostly passed away, meaning Hitler is now just a character in movies and books for most Americans—like Timur or Genghis Khan, the fear of a mass murderer fades with time. The Palestinian movement has effectively removed Jews from the left’s list of protected minority groups whose rights might be defended through unrest. Social media has led to overuse of the label “Nazi,” giving rise to the popular saying, “everyone I dislike is Hitler.”

Lyons is far more optimistic about this shift than I am. Personally, I think demonizing Hitler was a good idea. As a general moral principle, “don’t be Hitler” seems quite reliable. Even if you only care about Western power, someone who ideologically motivated military aggression, caused the end of European global empires, murdered over 20 million Slavs, destroyed Germany’s great-power status, and cemented Soviet rule over half of Europe seems like a solid example of what to avoid.

But Lyons believes that the end of anti-Naziism as a guiding Western principle will pave the way for a return of morality, community, rootedness, faith, and civilizational pride—things conservatives love:

Influential liberal thinkers like Karl Popper and Theodor Adorno helped convince the ideologically compliant postwar establishment that the fundamental sources of authoritarianism and conflict in the world were “closed societies.” These, according to Brague, are marked by the features of the “god of power”: strong beliefs and claims to truth, strong moral codes, strong interpersonal bonds, strong community identities and connections to place and past—in short, all the “objects of human love and loyalty, the passions and loyalties that bind a society together.”

Now, the unifying force of the god of power is seen as dangerous—the hellish source of fanaticism, oppression, hatred, and violence. Meaningful bonds of faith, family, and especially nation are now viewed with suspicion, as troublingly regressive temptations leading back to fascism...

The open society consensus and its weak gods have not produced a utopia of peace and progress, but instead led to civilizational disintegration and despair. As expected, history’s powerful gods were expelled, religious traditions and moral norms were debunked, community ties and loyalties weakened, distinctions and boundaries dismantled, and self-discipline handed over to top-down technocratic management. Unsurprisingly, this resulted in a lack of cohesion in nation-states and broader civilizations, let alone resilience against external threats from non-open, non-delusional societies. In short, the postwar open society consensus’s radical project of self-negation has turned into a collective suicide pact for Western liberal democracies.

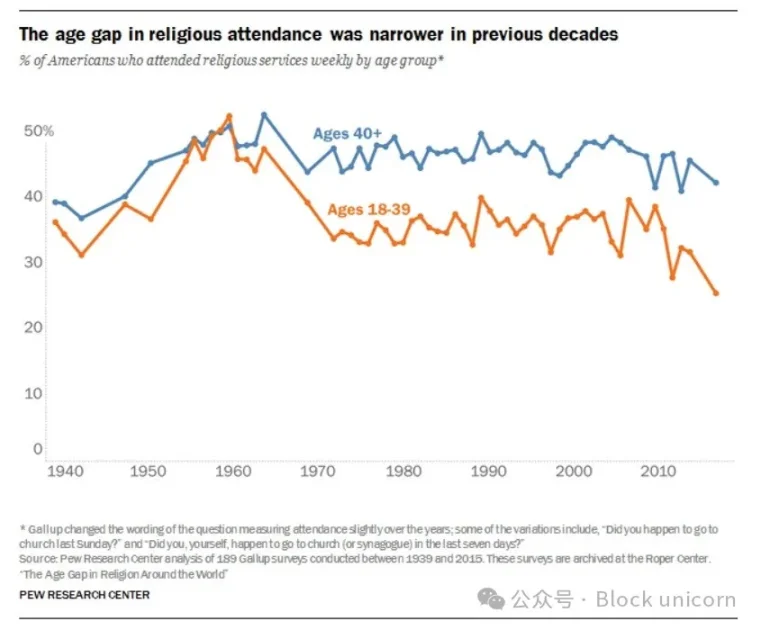

I’m not sure Lyons’ historical interpretation is correct. After all, as Robert Putnam documents in his book The Upswing, the decades after WWII in America saw the greatest surge in church participation, civic engagement, family formation, and social solidarity since the early republic. Here’s data on church attendance—soaring after WWII and remaining high through the 2010s for those over 40:

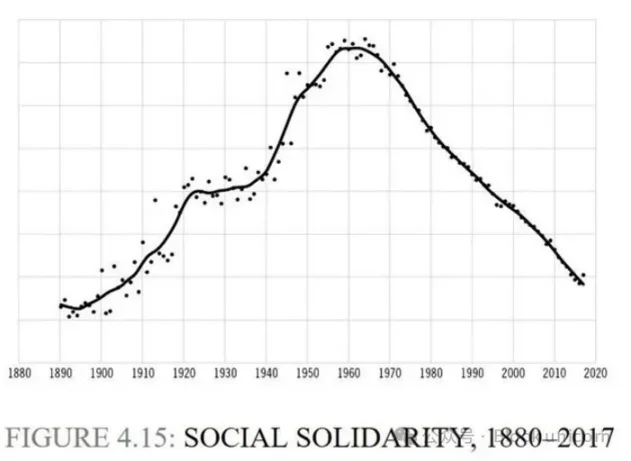

Here’s Putnam’s index of social solidarity, combining measures of civic and religious participation and family formation:

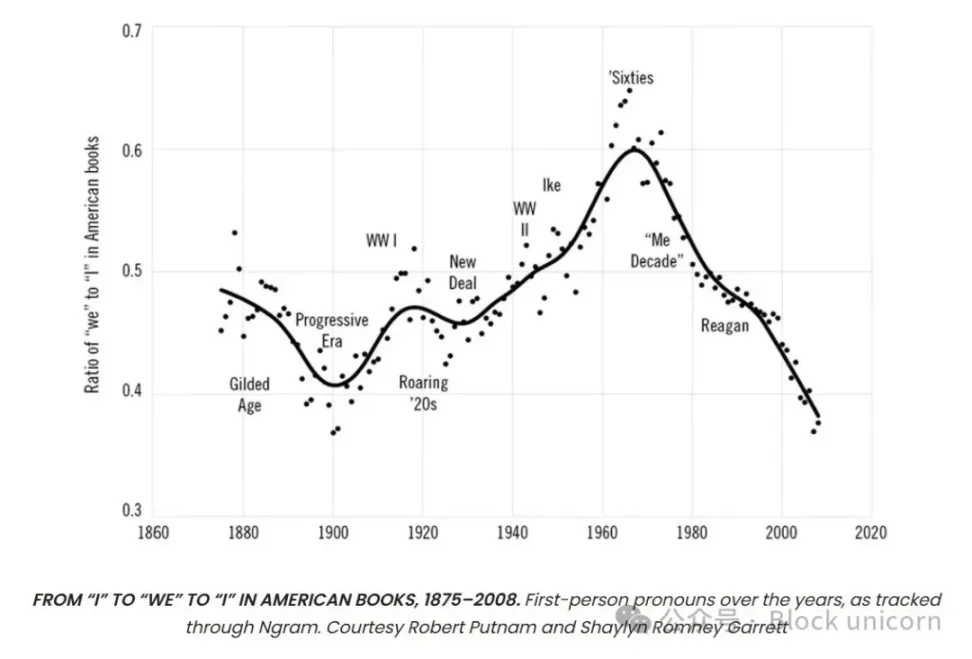

The New Deal and postwar era even witnessed a massive rise in the use of the word “we” replacing “I” in American books:

The “god of power” was never stronger than among the generation raised listening to Roosevelt preach liberalism on the radio and then going on to crush Adolf Hitler into dust. It isn’t hard to draw a causal line from the unifying struggle of WWII to the subsequent great American solidarity.

The Greatest Generation wholeheartedly believed Hitler was the devil on earth. Yet they did not view family, community, and tradition as little Hitlers to be smashed in defense of the open society. In fact, their society was both open and deeply rooted. My grandparents knew the names and life stories of every neighbor until the day they died; how many national conservative intellectuals or hardcore Trump fans can say the same?

Still, America’s “god of power” did eventually decline. Lyons believes Trump is bringing them back:

Mary Harrington recently observed that the Trump revolution appears both political and archetypal, noting that men’s widespread “excitement response” to Elon Musk and his recent work with his “young tech brotherhood” reflects a phenomenon that can “be understood archetypally as fighting a vast, misty enemy whose purpose is to destroy male heroism itself.” This masculine, thumotic spirit—ambitious vitality—was suppressed throughout the “long twentieth century,” but now it’s returning…

Today’s populism is… a long-repressed yearning for bold action, breaking free from the suffocating lethargy of procedural managerialism, passionately fighting for collective survival and self-interest. This is politics returning to politics. It demands a restoration of ancient virtues, including a vital sense of national and civilizational self-worth…

This is Trump, in all his ruggedness: the powerful gods have escaped exile and returned to America… Trump himself is an actor, not a thinker… he… embodies the entire rebellious new-world spirit overturning the old order… The boldness of Trump’s actions reflects more than partisan political maneuvering—it itself signifies the disruption of the stagnation of the old paradigm; now “you can just do things.”

The term “thumotic” here refers to Harvey Mansfield’s use of the Greek word “thumos” to denote political passion and drive. Francis Fukuyama spells it “thymos” and as early as 1992 predicted Donald Trump might embody the American thumotic impulse to dismantle the liberal establishment.

Thus, Lyons sees Trumpism as a Fight Club-style reassertion of wild, unapologetic male energy—only unlike Tyler Durden, who directed it toward anarchism, Lyons sees Trump and Musk unleashing their masculine passions by dismantling the civil service.

But Lyons never explains concretely how this destructive impulse will bring about the return of the “powerful gods” he desires. He treats the civil service and other postwar American institutions as obstacles to the revival of rootedness, family, community, and faith, but he doesn’t go beyond smashing these supposed barriers to envision actual reconstruction. He simply assumes it will happen naturally, or considers it a problem for the future.

I believe he will be disappointed. The Trump movement has existed for ten years now, and during that time it has built nothing. No Trump youth corps. No Trump community centers, Trump neighborhood associations, or Trump business clubs. Trump supporters haven’t flocked to traditional religion; Christian decline paused after the pandemic, but religious affiliation and church attendance remain far below turn-of-the-century levels. Republicans still have more children than Democrats, but birth rates in red states are falling too.

During Trump’s first term, right-wing efforts to organize civic engagement were laughably minimal. A few hundred “Proud Boys” gathered to brawl with antifascists in Berkeley and Portland. There were small-scale right-wing anti-lockdown protests in 2020. About two thousand showed up for the January 6 riot—mostly middle-aged men. None of this amounted to the kind of sustained grassroots organizing common in the 1950s.

For a tiny few, Trump’s first term was a live-action role-playing game; for everyone else, it was just a YouTube channel.

And so far in Trump’s second term? Nothing. Even rally attendance has dropped sharply. National conservatives who might have gone out to meet in 2017 now sit alone in their living rooms, swiping between X, OnlyFans, and DraftKings, throwing punches into the air when they read about Elon Musk and his team of computer nerds firing employees or Trump cutting aid to Ukraine. “You can just do things,” yet almost none of Trump’s supporters are actually doing anything—except passively cheering for their nominal team. Unless you’re one of the few geeks helping Elon Musk dismantle bureaucracy, this “thumos” is entirely secondhand.

You see, the MAGA movement is a digital phenomenon. It’s another vertical online community—a group of rootless, atomized individuals faintly connected across vast distances by illusory bonds of ideology and identity. It contains no family, community, or sense of rootedness in any place. It’s a digital consumer product. It’s a subreddit. It’s a fan club.

N.S. Lyons and the national conservatives completely misunderstand why America abandoned rootedness, community, family, and faith. We gave up these “powerful gods” not because liberals were too harsh on old Adolf. We gave them up because of technology.

In the 1920s, America began experiencing mass affluence alongside technologies that granted individual humans unprecedented autonomy and control over their physical location and access to information. Car ownership allowed Americans to travel anywhere, anytime, freeing them from ties to specific places. Telephone ownership enabled remote communication. Radio and television exposed them to new ideas and cultures, and the internet exposed them to even more.

Then came social media and smartphones. Suddenly, “society” no longer meant the people in your physical vicinity—your neighbors, coworkers, gym buddies, and so on. Instead, “society” became a collection of avatars typing words at you on a small glass screen in your pocket. Your phone became where you met and talked with friends and loved ones, and also where you argued about politics and ideas. People’s roots shifted from physical space to digital space.

Mounting evidence shows that smartphone-enabled social media correlates with feelings of isolation and alienation, loneliness and solitude, declining religious belief, reduced family formation, and lower birth rates. The car, telephone, television, and internet of the twentieth century made American society somewhat detached, but it managed to resist partially and retain some remnants of rootedness. Yet smartphone-powered social media broke through these last lines of resistance, turning us into free-floating particles drifting in an intangible space of memes, identities, and distractions.

It turns out the powerful gods are more fragile than the new gods forged in silicon.

The very people N.S. Lyons now celebrates are, more or less, the ones who accomplished this. Not Elon Musk himself—he just builds cars and rockets. But Steve Jobs, Jack Dorsey, Zhang Yiming, and a legion of ambitious, wealth-seeking entrepreneurs who followed them constructed the virtual worlds that have become our truest homes.

I’m not saying they did this out of malice. Technology in advanced societies has a way of advancing; if it can be built, it likely will be. No one can foresee all its downsides ahead of time. But ironically, the very people Lyons now believes will usher in a new age of rootedness and community are precisely those who destroyed the old one.

But anyway, yes, this thing will fail, because nothing has been built. Yes, every ideological movement assures us that once the old order is thoroughly demolished, a utopia will arise in its place. Somehow, the utopia never arrives. Instead, the period of supposed temporary pain and sacrifice grows longer, and the ideologues in charge grow increasingly zealous about blaming enemies and purging counterrevolutionaries. At some point, it becomes clear that the promise of utopia was merely a pretext for eliminating enemies—the “thumos” itself becomes the goal.

Trump’s Treasury Secretary has told us the economic pain caused by Trump is just a “detox period.” Trump blames stock market declines on “globalists.” Trump’s Justice Department blames egg prices on hoarders and speculators. If you don’t recognize this script, you haven’t been paying attention to the news—or history.

Simply smashing the old order won’t create anything. The Visigoths and Vandals built nothing atop the ruins of Rome. They indulged their “thumos,” looted wealth for a while, then vanished into myth and memory.

For the past fifteen years, I’ve watched with dismay as the real-world communities and families I knew in my youth have been torn apart, replaced by a jumble of fictional online identity movements. I’m still waiting for someone to figure out how to rebuild society—how to do what Roosevelt and the Greatest Generation did a century ago. Watching the MAGA movement, I’m certain this isn’t the answer.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News