ScaleBit Deep Selection: A Comprehensive Analysis of Security Vulnerabilities and Attack Surfaces in the Blockchain Ecosystem

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

ScaleBit Deep Selection: A Comprehensive Analysis of Security Vulnerabilities and Attack Surfaces in the Blockchain Ecosystem

The report provides a detailed analysis of current security vulnerabilities and attack surfaces.

Although blockchain technology demonstrates significant potential in decentralization, security, and trust mechanisms, its ecosystem still harbors various security risks. From vulnerabilities in L1/L2 cross-chain communication—such as failure to account for block rollbacks, improper handling of transaction failures, and light client verification flaws—to risks in Cosmos application chains related to module ordering, random number usage, and transaction rollback issues, and further to script construction, UTXO handling, and rollback risks within Bitcoin's expanding ecosystem, all pose serious challenges to blockchain applications. Meanwhile, common errors in smart contracts or general-purpose programming languages—such as integer overflows, infinite loops, race conditions, and unhandled exceptions—greatly threaten system availability and security.

In addition, the inherent fragility of P2P network architectures—including Sybil attacks and Eclipse attacks—as well as DoS attacks can hinder the efficiency and reliability of blockchain systems. Cryptographic vulnerabilities—such as insecure hash algorithms, weak signature schemes, and unsafe random number generation—further threaten data confidentiality and integrity. Improper handling of components at the ledger level, such as transaction mempools, orphan blocks, and Merkle trees, may lead to on-chain data inconsistency or asset loss. Finally, inadequately designed economic models and governance mechanisms could result in imbalanced network incentives or even network splits, allowing attackers to exploit these imbalances to undermine system stability.

In view of these risks, only through deep understanding and rigorous preventive measures can the security and sustainable development of the evolving blockchain ecosystem be ensured. At the end of 2024, BitsLab, the parent brand of ScaleBit, released the "2024 Panoramic Observation and Security Research Report on Emerging Public Chain Ecosystems." This report provides a detailed analysis of existing security vulnerabilities and attack surfaces, offering rich and practical insights. This article extracts key sections from that report, aiming to highlight critical security vulnerability types within the blockchain ecosystem, helping readers prepare proactively and collectively promoting the industry’s secure and healthy development.

Read the full report: https://bitslab.xyz/reports-page

1) List of Security Vulnerability Types

1.1 L2/L1 Cross-Chain Communication Vulnerabilities

Cross-chain communication is a crucial means of enhancing interoperability across blockchain ecosystems, yet it introduces numerous security risks during implementation. Key concerns include:

L2 does not consider L1 block rollbacks

When sending L1 transactions or retrieving on-chain data from L1, failing to account for block reorganizations may lead to asset loss.

L2 does not verify whether transactions sent to L1 have succeeded

Transactions may fail due to network congestion or insufficient gas fees. If this possibility is ignored, it could result in asset losses for projects or users.

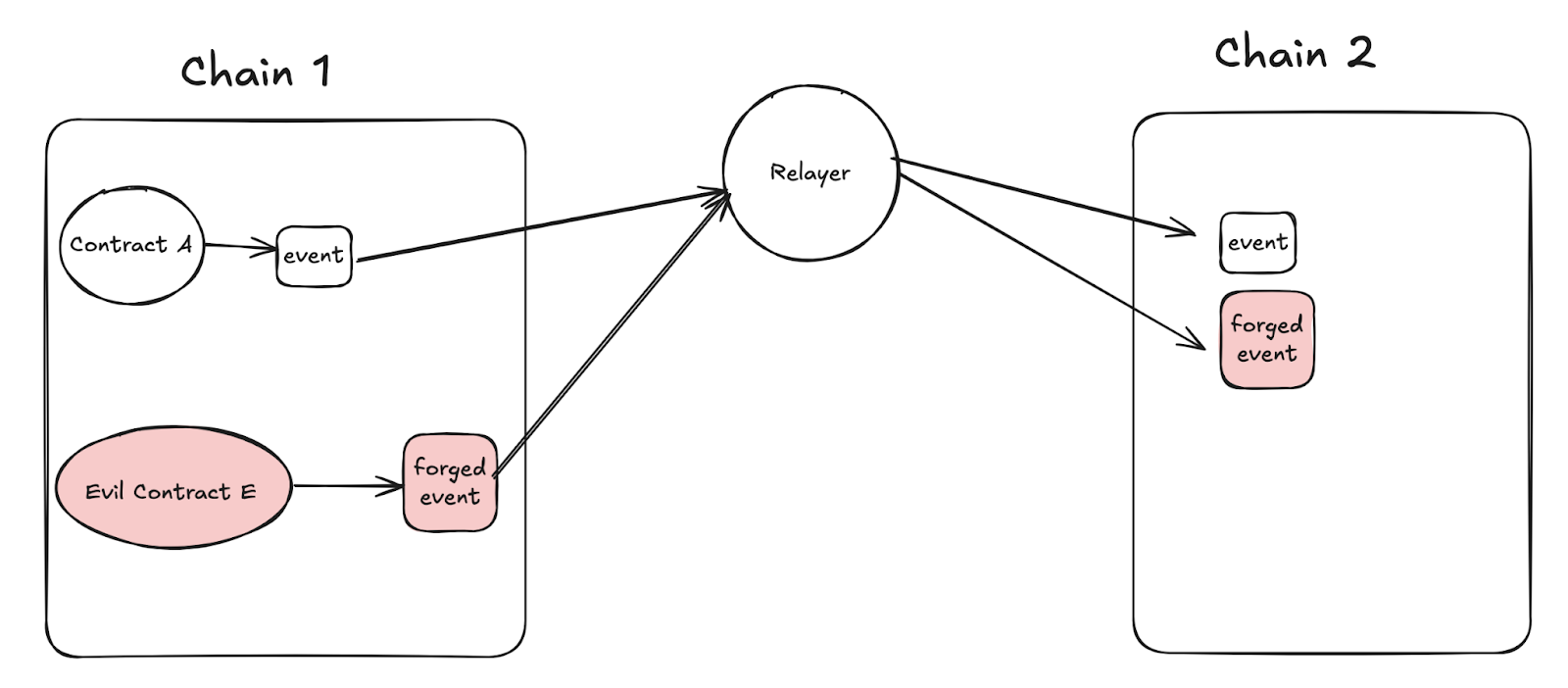

Forged on-chain events

If a cross-chain bridge listens to on-chain events without verifying their origin contract address, other contracts may forge such events.

A single transaction contains multiple on-chain events

A transaction may emit multiple events. Failure to handle this scenario properly could lead to asset loss for projects or users.

Light client verification vulnerabilities

1. PoW chains do not consider private mining attacks

2. Failure to use officially recommended algorithms

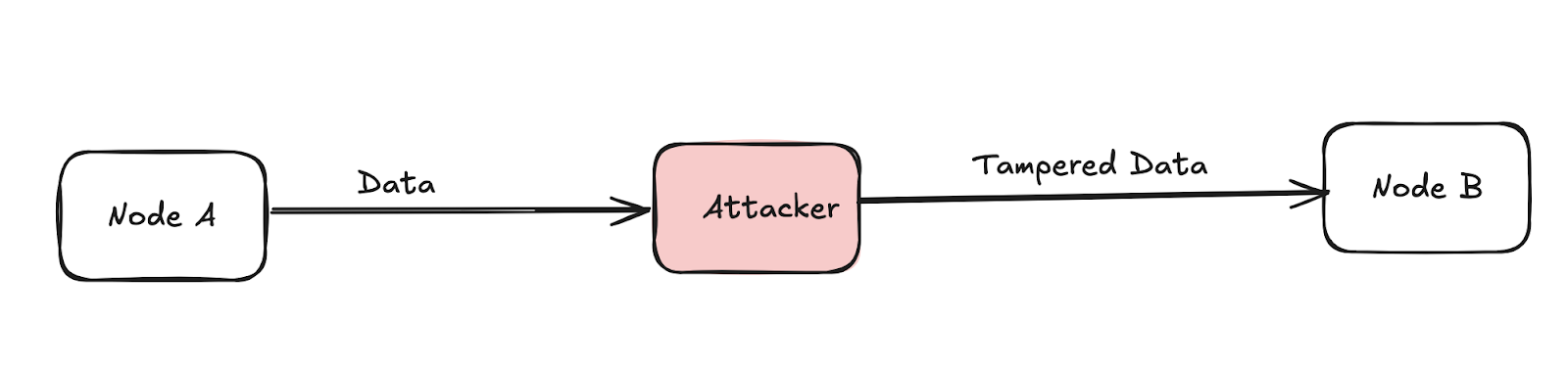

Man-in-the-middle (MitM) hijacking

Message transmission mechanisms are critical in L2/L1 cross-chain communication, requiring message integrity and confidentiality. Messages passed between chains risk being tampered with or eavesdropped upon; thus, encryption must be used to protect information. Additionally, non-repudiation during inter-chain message forwarding is essential to prevent malicious alterations.

Latency and finality issues

Cross-chain communication often faces latency and finality challenges. Due to differences in consensus mechanisms and confirmation times across chains, cross-chain transaction confirmations may vary, leading to delayed state updates and increased security risks. When designing cross-chain protocols, finality definitions must be clearly established to ensure transaction state consistency and prevent double-spending or inconsistent states caused by delayed confirmations.

1.2 Cosmos Application Chain Vulnerabilities

Cosmos is an ecosystem centered on blockchain interoperability, enabling different blockchains to connect via IBC (Inter-Blockchain Communication Protocol). However, Cosmos application chains may also harbor certain vulnerabilities and security risks during implementation. Key concerns include:

BeginBlocker and EndBlocker crash vulnerabilities

BeginBlocker and EndBlocker are optional methods developers can implement in modules, triggered at the beginning and end of each block respectively. Using panics to handle errors in BeginBlock or EndBlock functions may cause the chain to halt when an error occurs.

Incorrect use of local time

Different nodes may have varying local times. If discrepancies are not considered during consensus generation, consensus failures may occur.

Reference material:

Image source

https://forum.cosmos.network/t/cosmos-sdk-security-advisory-jackfruit/5319

Improper use of random numbers

Different nodes generate different random numbers. If this variance is not accounted for during consensus generation, it may lead to consensus issues.

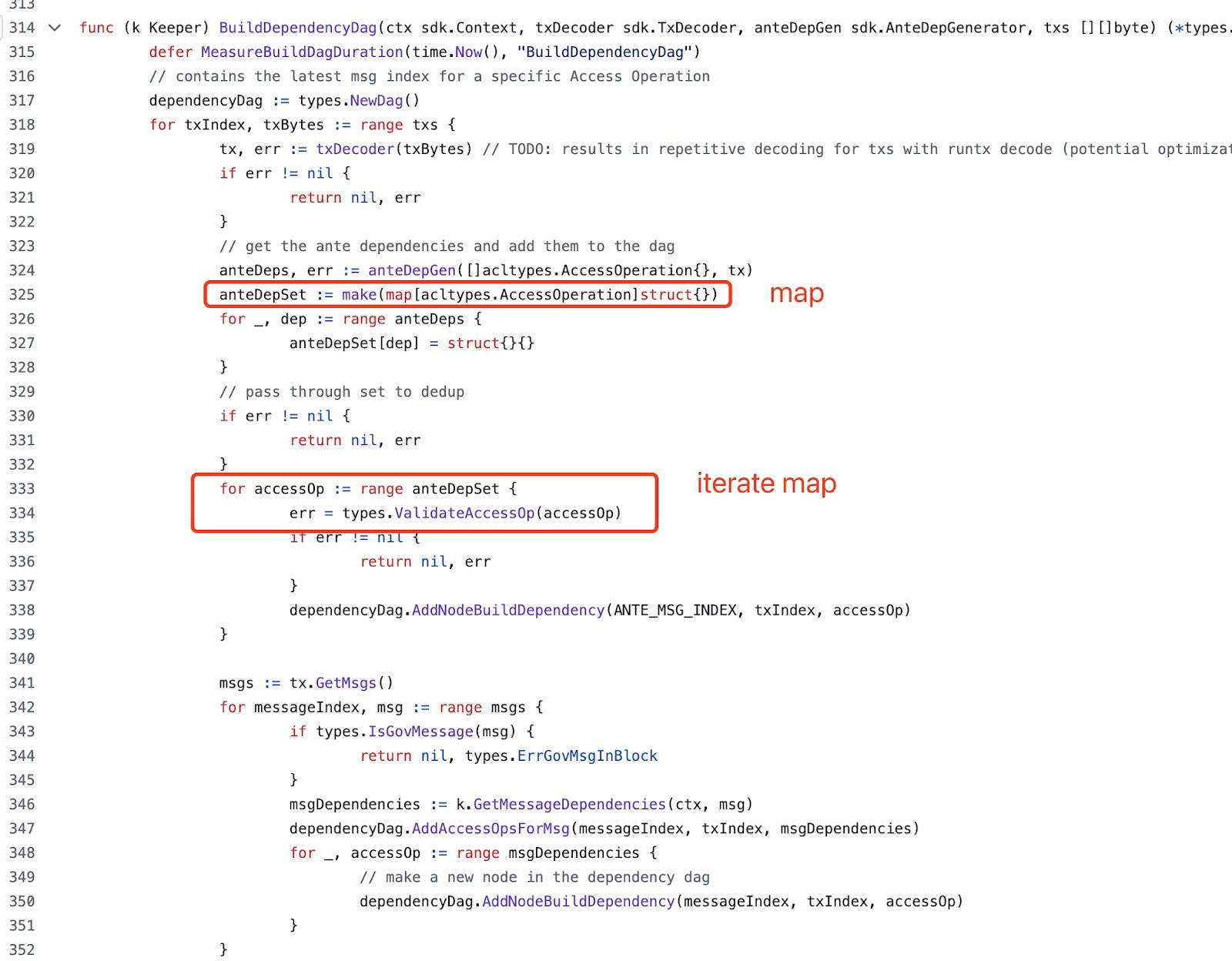

Incorrect use of map iteration functionality

Map iteration in Go is non-deterministic. If this is not handled correctly during consensus generation, it may result in consensus failure. Example code:

Security issues caused by unreasonable module ordering

Cosmos application chains consist of multiple modules, some of which require specific execution orders during event processing. Improper ordering may introduce security risks.

Transaction failure without state rollback

In Cosmos application chains, if a transaction fails but the system design fails to roll back the state to its pre-execution condition, on-chain data inconsistency may occur. This undermines user trust and may lead to financial loss. Therefore, designs must ensure smart contracts properly handle failed transactions, maintaining state consistency and reliability, including implementing automatic rollback mechanisms where necessary.

Inaccurate state validation

State validation logic in Cosmos application chains must be rigorous. Inaccurate validation may allow invalid transactions to be confirmed, compromising chain security. Developers should carefully design state transition logic and conduct comprehensive testing to prevent vulnerabilities arising from flawed validation.

Cross-chain message transmission security

The IBC mechanism enables message transfer between different application chains but introduces potential security risks. For example, if messages are tampered with during transit, incorrect state updates or malicious operations by attackers may occur. Encryption and digital signatures should be employed to ensure message integrity and authenticity, preventing tampering.

Smart contract upgrade and version management issues

Contracts on Cosmos application chains may require upgrades. Poorly executed upgrades may lead to incompatibility with previous contract states or introduce new vulnerabilities. Developers should establish clear upgrade strategies, including version control and migration plans, ensuring normal chain operation throughout the upgrade process.

Economic model and incentive mechanisms

The design of economic models in the Cosmos ecosystem directly affects chain security and stability. Unreasonable incentive structures may lead to participant behavior imbalance or economic attacks. Economic models should be thoroughly evaluated to ensure they effectively maintain network security and health.

Governance mechanism vulnerabilities

Governance mechanisms in Cosmos application chains allow token holders to participate in decision-making. Poorly designed governance may lead to governance attacks or centralization. Governance fairness and transparency must be ensured to prevent minority manipulation of chain decisions.

1.3 Bitcoin Expansion Ecosystem Vulnerabilities

Bitcoin script construction vulnerabilities

Bitcoin scripts are often generated dynamically and deployed onto Bitcoin, frequently incorporating user-provided data. Insecure script construction may lead to asset loss.

Vulnerabilities due to unconsidered derivative assets

Common Bitcoin derivative assets include inscriptions and runes. If L2 systems only consider native BTC when handling user assets and ignore derivatives, user assets may be lost.

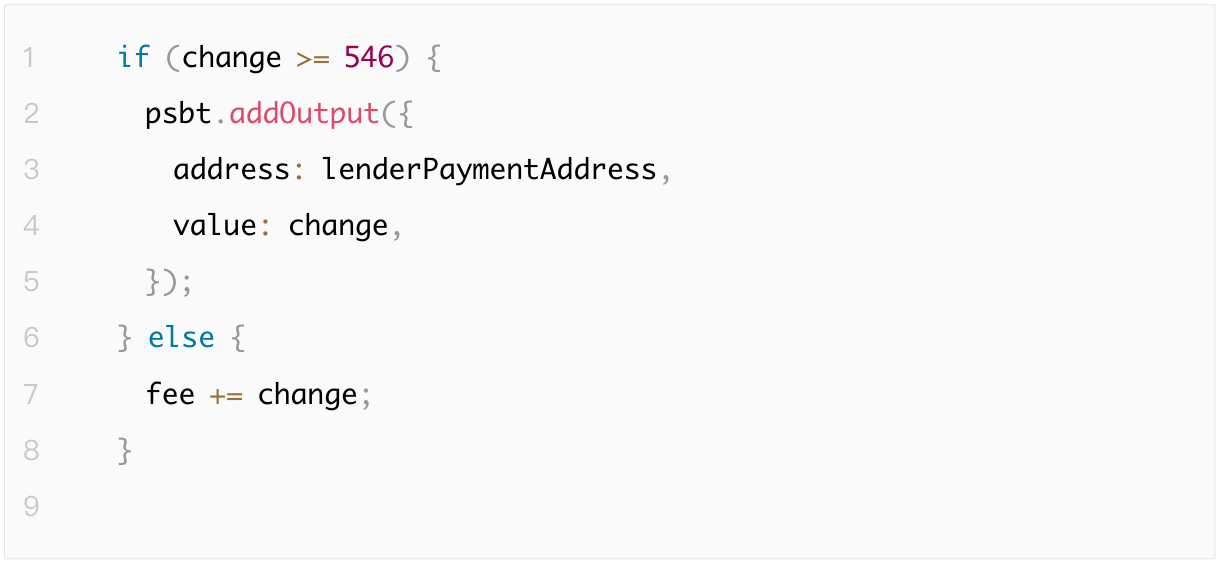

UTXO amount calculation error vulnerabilities

1. Mistakes in transaction fee calculation

2. Mistakes in change amount calculation

For example, in the following code, the change output is only included if the change amount is greater than or equal to 546 satoshis—the dust limit for traditional P2PKH transactions. However, dust limits vary across address types. Taproot addresses, for instance, have a lower dust limit of 330 satoshis.

This hardcoded value does not account for Taproot's lower dust threshold, potentially resulting in loss of small assets in transactions involving Taproot addresses. Detailed information about dust limits for various address types can be found in Bitcoin Core source code and discussions on BitcoinTalk.

https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=5453107.msg62262343#msg62262343

Failure to detect whether UTXO contains "op_return"

UTXOs containing "op_return" are unspendable.

SPV verification vulnerabilities

1. Block header timestamp not verified

2. Proof-of-work in block headers not verified

Failure to consider rollback scenarios

As Bitcoin operates on PoW, block reorganizations occur frequently. Failing to account for this during transaction submission or data retrieval may result in asset loss.

Failure to verify Bitcoin transaction success

Submitted Bitcoin transactions may not be immediately mined. Their status must be monitored to confirm on-chain inclusion. Third parties may construct higher-fee transactions to delay confirmation of L2-submitted transactions, leaving them stuck in the mempool.

Mixing up absolute and relative time locks

Confusing these two types of time locks in Bitcoin script construction may severely result in asset loss.

Unreasonable time settings in Hash Time-Locked Contracts (HTLC)

Common issues include:

1. Time set too large

2. Time set too small

3. L1 and L2 clocks out of sync

1.4 Common Programming Language Vulnerability Types

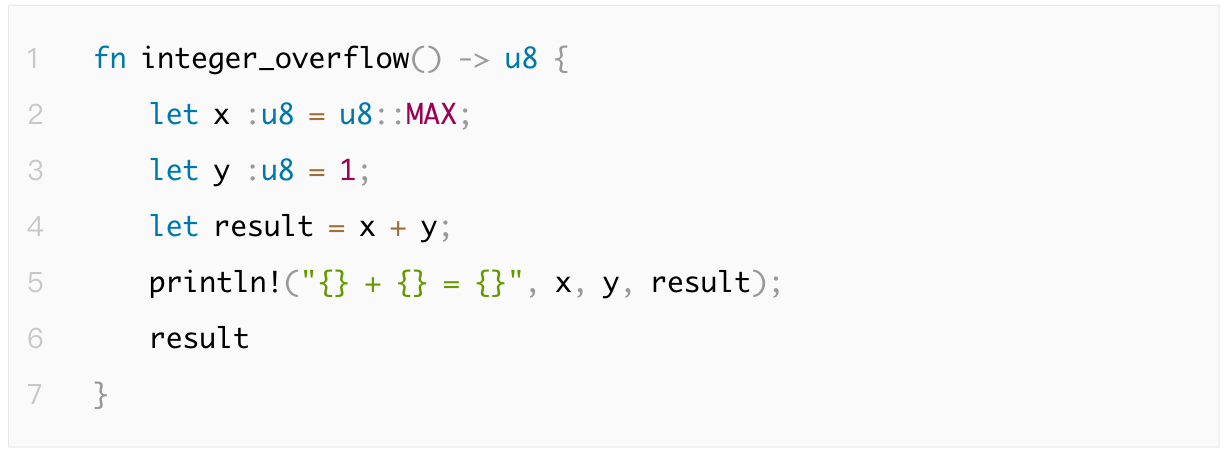

1.4.1 Integer Overflow

An integer overflow occurs when a numeric value exceeds the range representable by its type, causing wraparound or logical errors that compromise data accuracy. Rust automatically detects overflows in debug mode, whereas Go requires manual boundary checks.

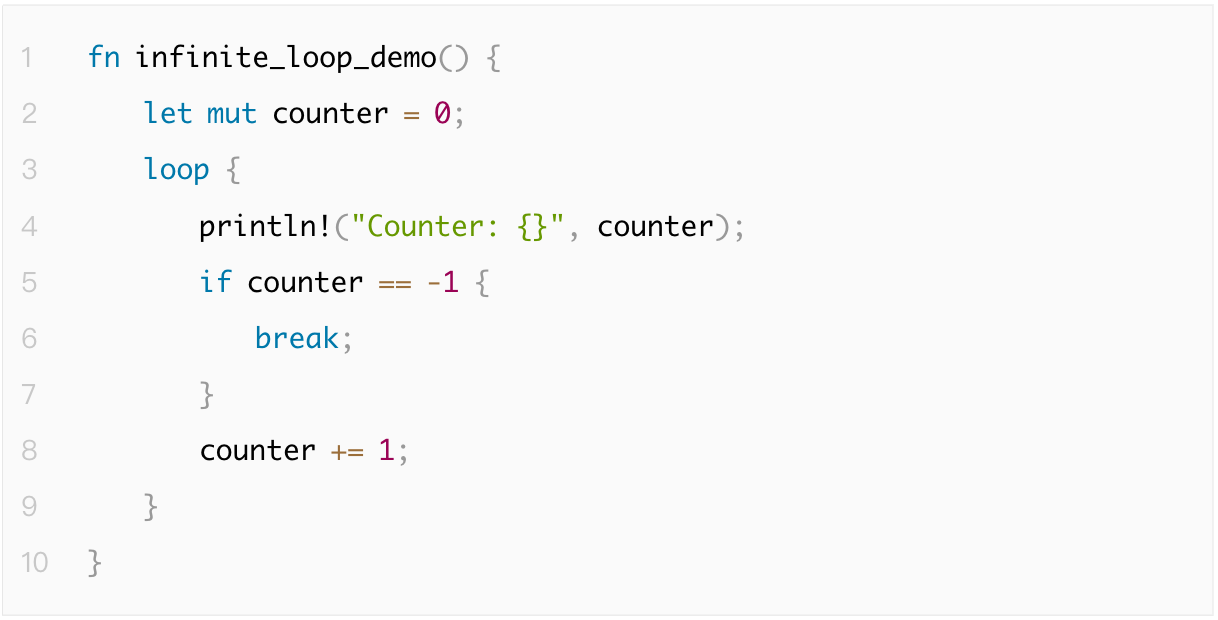

1.4.2 Infinite Loops

An infinite loop occurs when a program enters a never-ending loop under certain conditions, consuming system resources and causing the program to hang or become unresponsive. Prevention involves setting proper loop exit conditions and using Rust's timeout mechanisms or Go's context package to manage long-running loops.

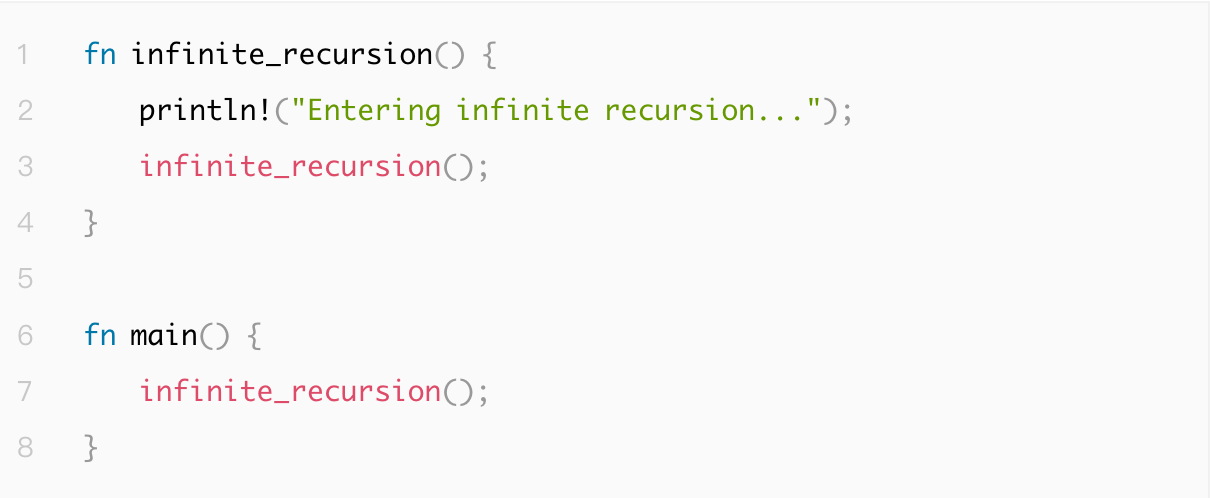

1.4.3 Infinite Recursive Calls

Infinite recursion happens when recursive functions lack termination conditions, leading to stack overflow and crashes. Ensuring recursive functions have clear base cases and limiting recursion depth according to requirements can effectively prevent this issue.

Rust displays stack overflow errors in debug mode, similar to the following output:

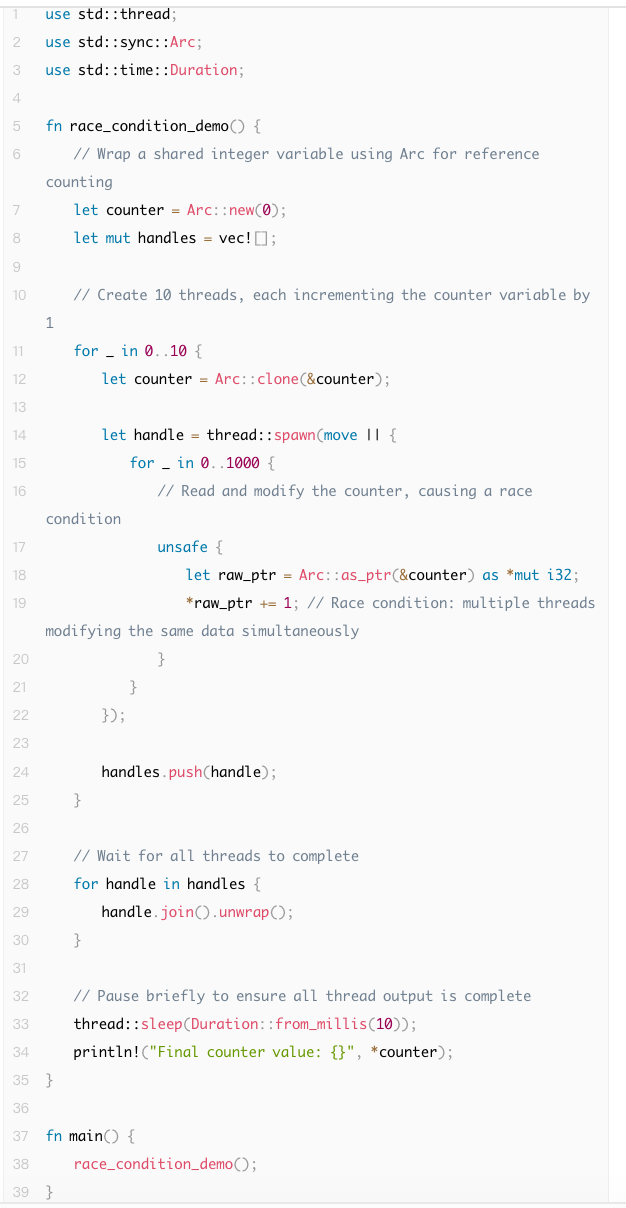

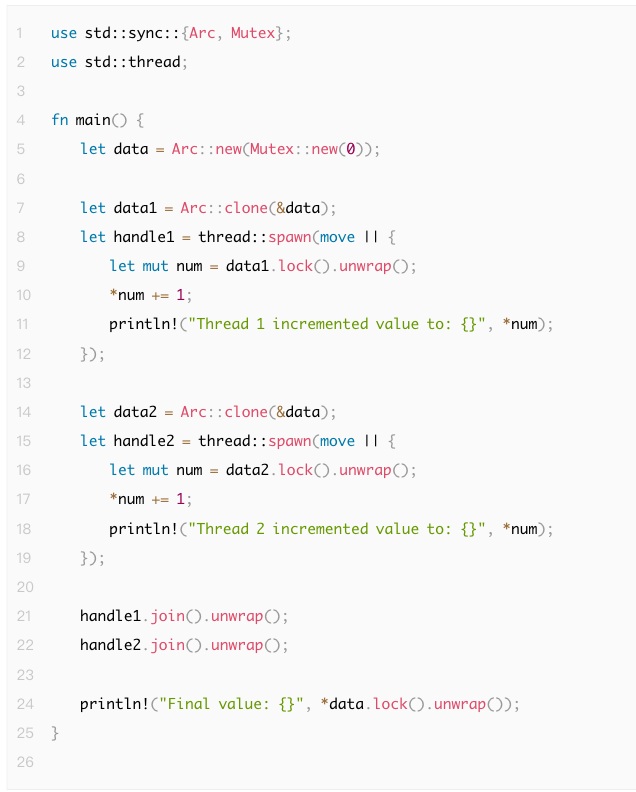

1.4.4 Race Conditions

Data races occur when multiple threads access shared resources without synchronization, resulting in data inconsistency. Rust prevents data races through ownership and thread-safe libraries, while Go offers concurrency support via channels and the sync package.

The following Unsafe Rust example shows two threads simultaneously accessing and modifying a shared variable, leading to undefined behavior. This code causes a data race due to the absence of any synchronization mechanism protecting the shared resource:

While Safe Rust prevents data races, logical race conditions may still occur. A logical race condition refers to unexpected behaviors arising under specific execution sequences. Examples include:

1. Time-sensitive operations: The order of operations between two threads may affect the final outcome. For example:

a. One thread checks a condition while another modifies it in between. In Rust, Arc<Mutex<T>> can coordinate access order, but cannot prevent logical race conditions.

2. Double-checked locking: Multiple threads attempting to initialize a shared resource may both believe it is uninitialized, leading to logical errors. While no data race occurs, unexpected logical errors may arise.

3. Incorrect lock ordering: If multiple locks are used, threads acquiring them in inconsistent orders may cause deadlocks. Rust's type system cannot prevent this kind of deadlock-related race condition.

Below is a demonstration of a race condition vulnerability in Safe Rust. In this example:

● Two threads increment the shared variable data by 1. Each thread locks data before incrementing.

● Because the operation is stepwise, even though data is protected by a Mutex, the execution order of Thread 1 and Thread 2 affects the final print output. Theoretically, the final value should be 2, but the actual printing order may vary.

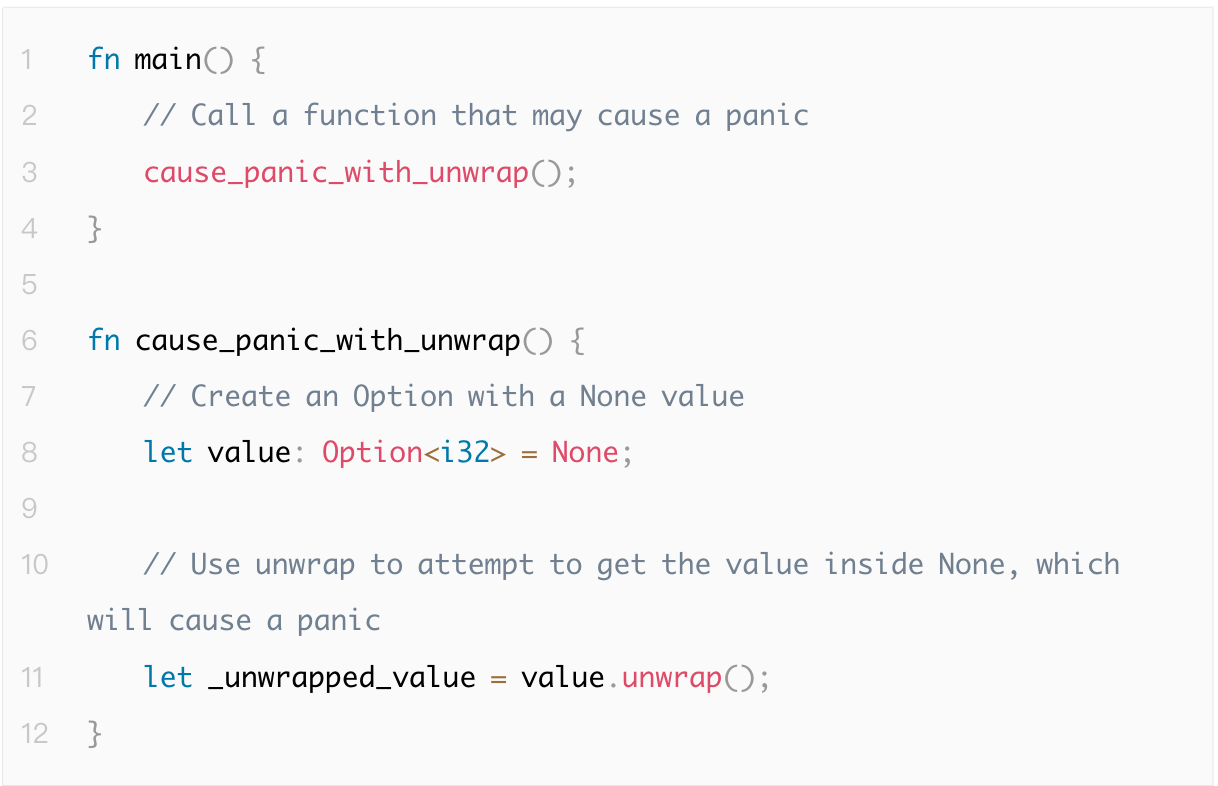

1.4.5 Unhandled Exceptions and Crashes

Crashes are typically triggered by unhandled errors, causing unexpected program termination. Go uses defer/panic/recover to capture exceptions, while Rust employs Result and Option types for more robust error handling.

Below is an example where uncaught panic leads to program crash:

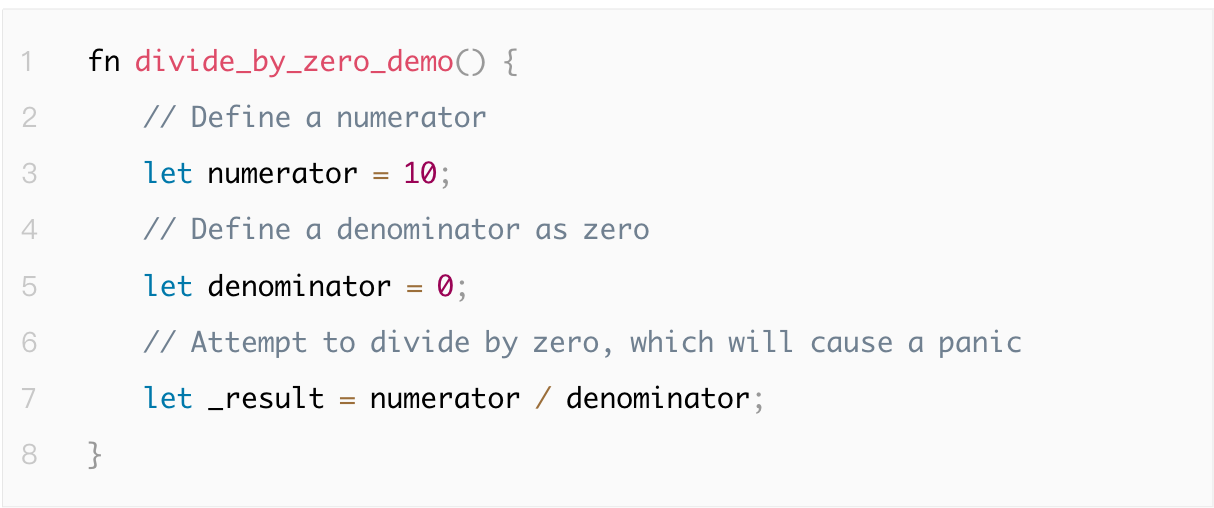

1.4.6 Division-by-Zero Vulnerability

A division-by-zero vulnerability occurs when a program performs division with zero as the denominator, potentially triggering exceptions or crashes. It is recommended to check the denominator before division to prevent zero-value operations and ensure program stability.

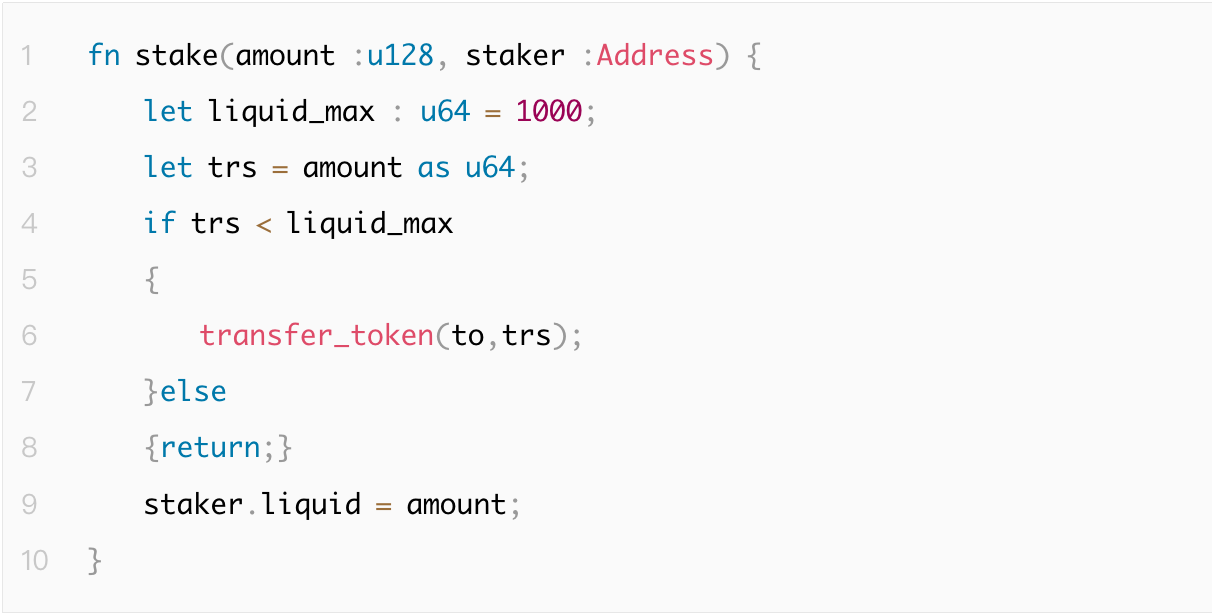

1.4.7 Type Conversion

Type conversion errors usually stem from unsafe or incompatible conversions, possibly leading to unpredictable behavior. Both Go and Rust warn about type incompatibility during conversion, with Rust being stricter and requiring explicit use of the "as" operator.

In the following example, a user adds liquidity of amount tokens, and the system records their liquidity balance. If amount = (u128::MAX << 64) | 1, the user actually pays only 1 token, but the recorded liquidity balance becomes 340282366920938463444927863358058659841.

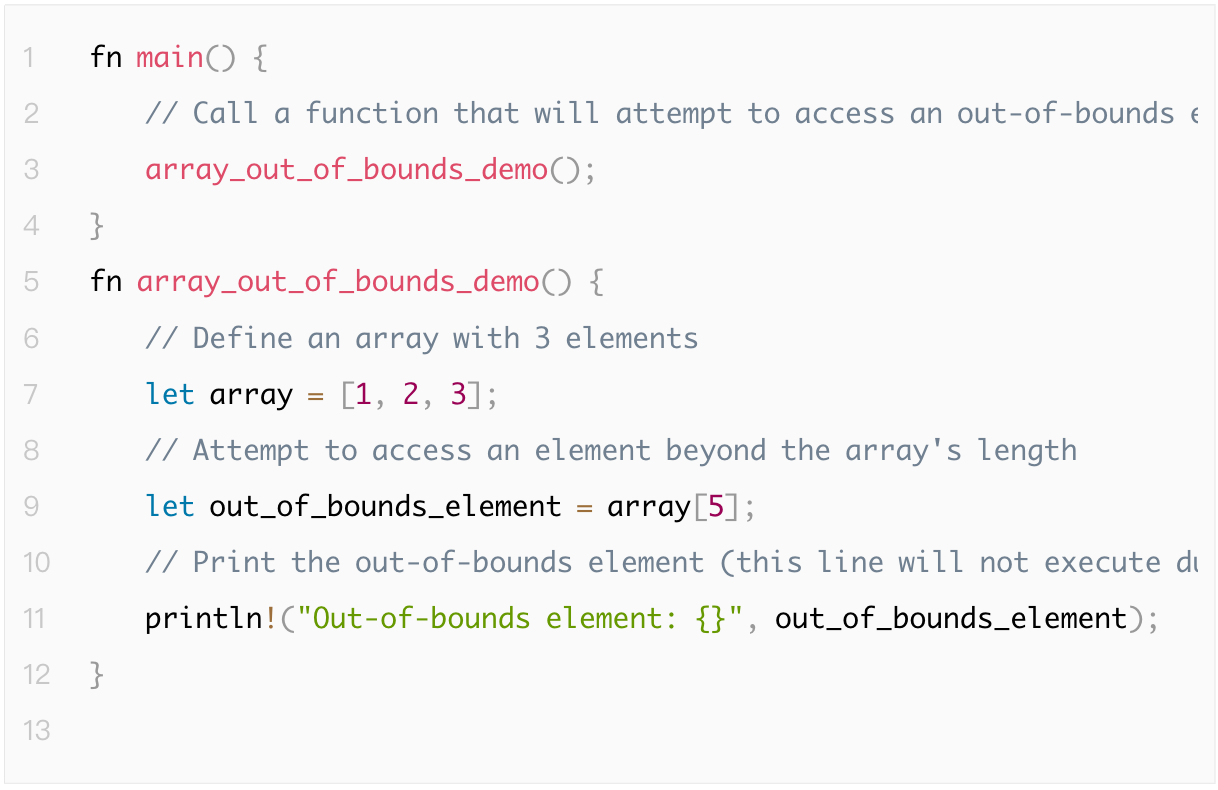

1.4.8 Array Out-of-Bounds Access

Array out-of-bounds access refers to accessing invalid indices in an array, causing memory access errors or program crashes.

The following example demonstrates how out-of-bounds access causes a program crash:

1.5 P2P Network Vulnerabilities

P2P (peer-to-peer) networks enable direct connections and communications among distributed nodes in blockchain systems. Despite providing foundational networking for decentralized systems, P2P networks face various security vulnerabilities and attack risks.

From a security perspective, P2P networks fall into two categories: permissionless, commonly used in L1s, and permissioned, more prevalent in L2s.

In permissionless P2P networks, many attacks are based on Sybil attacks. In permissioned networks, we cannot assume all nodes are trustworthy; from a security standpoint, at least one malicious node must be assumed.

Common P2P network vulnerability types include:

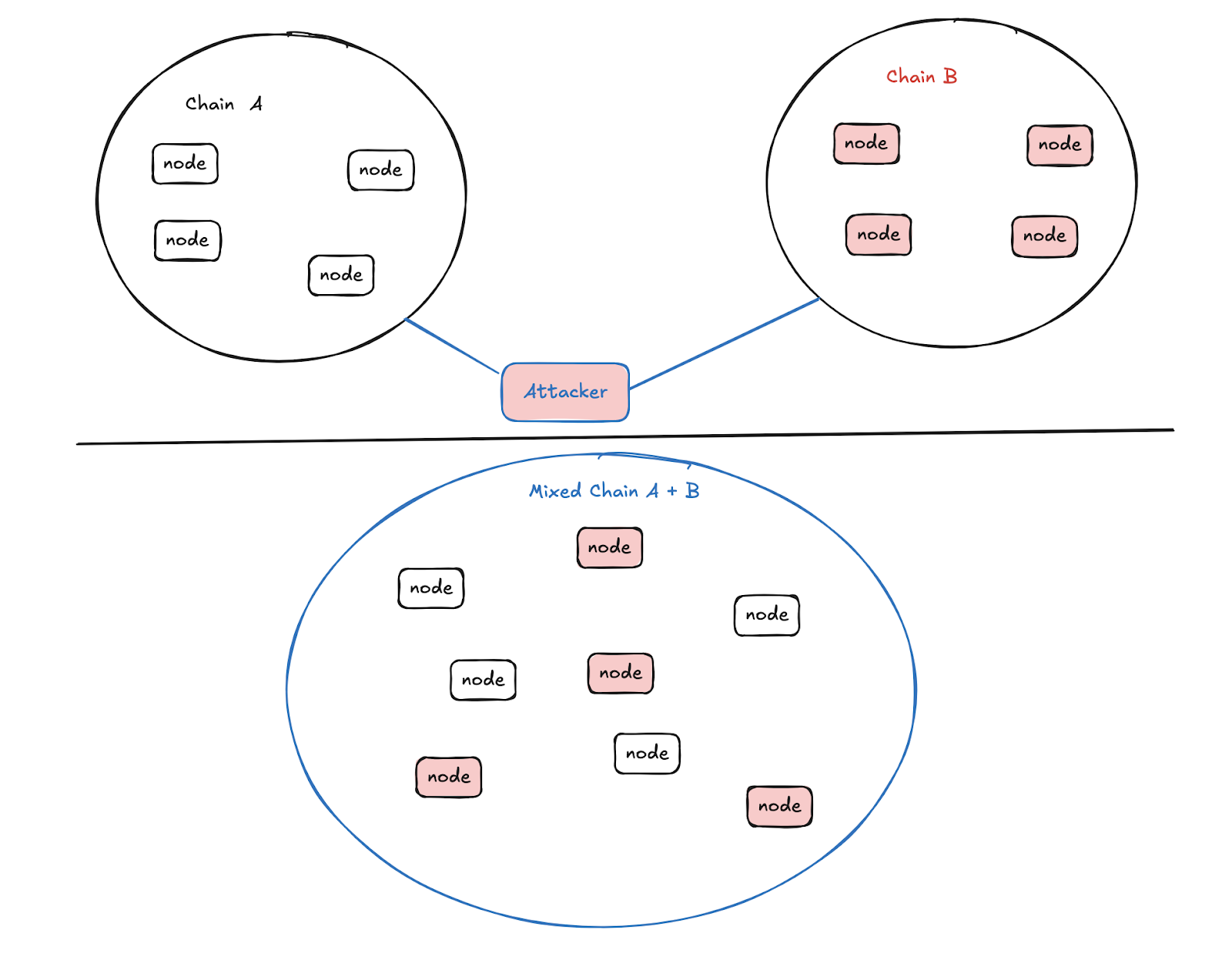

1. Alien Attack (Address Pool Poisoning):

An alien attack, also known as address pool poisoning, involves inducing nodes from similar chains to infiltrate and pollute each other. The root cause is that similar chain systems fail to identify non-native nodes in their communication protocols.

Ethereum-like chains have previously exhibited such vulnerabilities. Chains compatible with Ethereum’s P2P discv4 node discovery protocol—including Ethereum and Ethereum Classic—use compatible handshake protocols and cannot distinguish whether nodes belong to the same chain, resulting in mutual address pool contamination, degraded node communication performance, and ultimately node blocking.

The attack process is illustrated below:

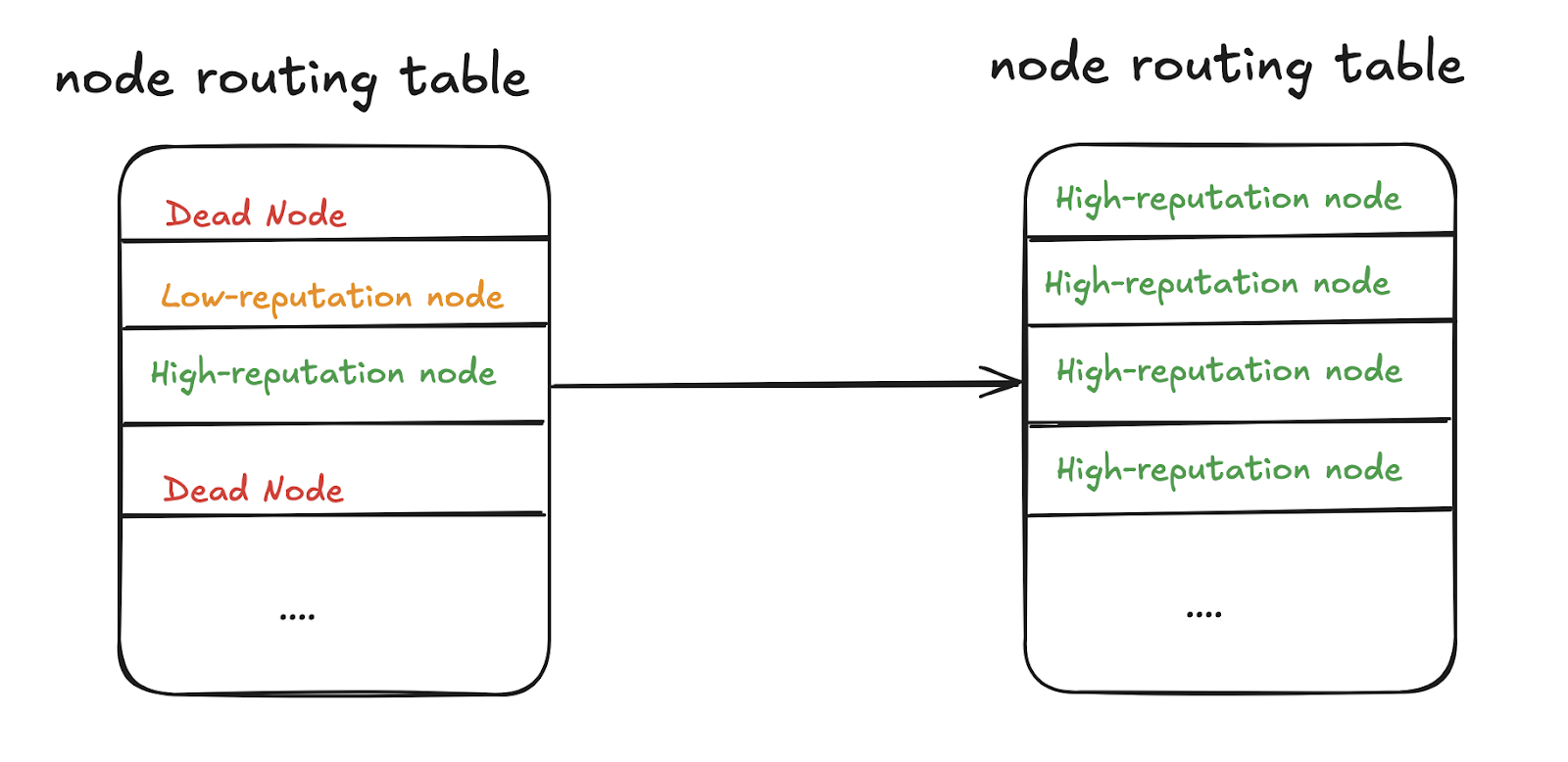

2. Lack of Trust Model Mechanism

Establish reputation scores for each node, adjusting trust levels based on historical behavior. For example, nodes frequently sending invalid data should have their reputation reduced. High-reputation nodes are more trusted, while low-reputation nodes face restrictions.

3. Lack of Node Quantity Limitation Mechanism

Limit the rate of new node creation or the number of connections per IP to prevent rapid creation of numerous fake nodes.

4. Node Discovery Algorithm Issues

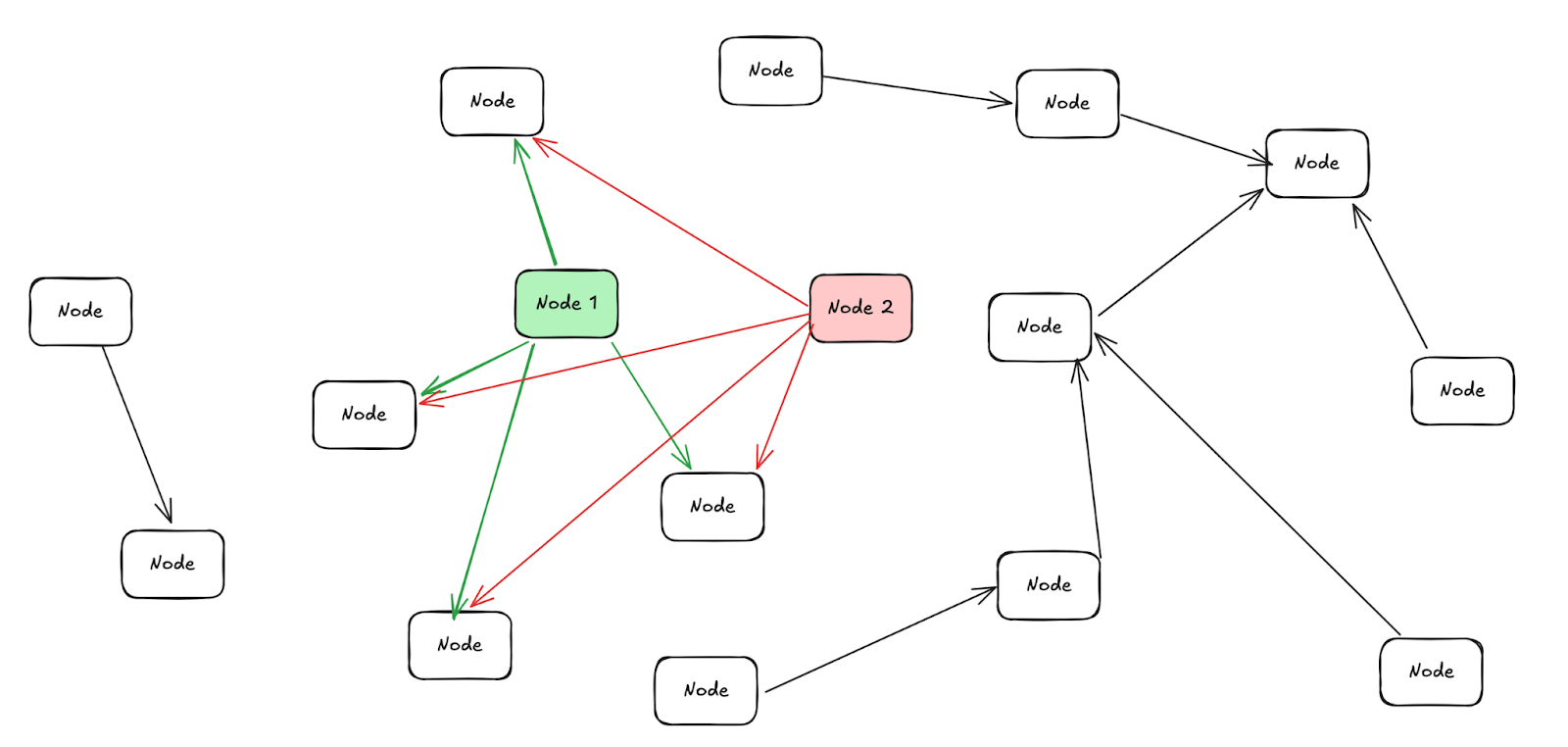

Node discovery and selection algorithms locate and connect new nodes in P2P networks. Poorly designed algorithms—such as unbalanced distance calculations—can easily lead to imbalanced network topologies and overloaded nodes. Algorithms must ensure balance and unpredictability to enhance node distribution security and network resilience against attacks.

The image below illustrates an extreme case of network topology imbalance:

5. Vulnerable Node Selection Mechanisms

If a node uses a vulnerable node selection mechanism, all its connected peers might be malicious, leading to an Eclipse Attack. Common secure node selection mechanisms include:

Random node selection: Randomize connection targets to make it difficult for attackers to control connection structure.

Local connection strategy: Prioritize connections with physically or topologically nearby nodes, making it harder for attackers to penetrate the entire network.

6. Lack of Authentication

In permissioned P2P networks, node identities must be authenticated.

7. Lack of Periodic Routing Table Update Mechanism

If a node returns invalid data, its entry in the routing table should be considered for removal.

Nodes should periodically remove inactive nodes from the routing table and replace them with new ones, avoiding network isolation due to stale routing tables.

8. Man-in-the-Middle Hijacking Vulnerability

Data transmitted over P2P networks must maintain integrity. If incorrect or flawed encryption algorithms are used, data may be tampered with.

1.6 DoS Vulnerabilities

DoS (Denial-of-Service) vulnerabilities exhaust system resources, blocking legitimate user access. Key types include:

1. Memory Exhaustion Attacks

Exploit high memory demands to overwhelm the system. Prevent by setting resource limits.

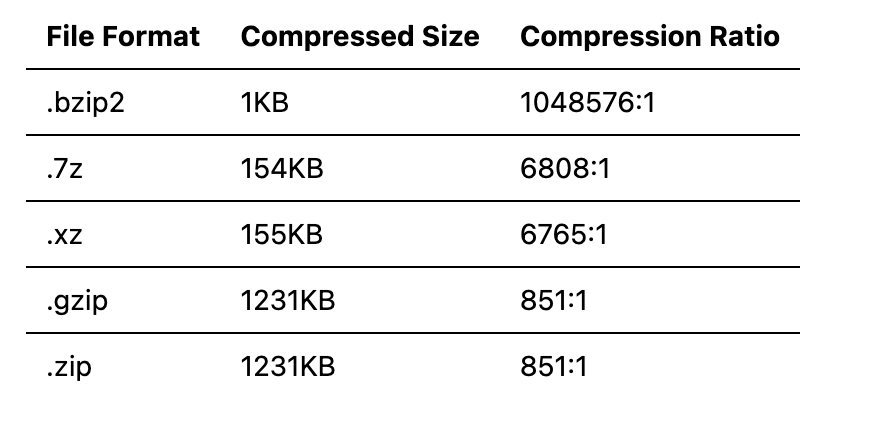

A common memory exhaustion attack is the "zip bomb." The basic principle involves generating a very large file filled entirely with zeros (or repeated values), then compressing it into a zip file. Due to the high compression ratio of repetitive content, the resulting zip file is extremely small. When the target decompresses this file, it consumes enormous memory to store the expanded data, rapidly exhausting available memory and crashing the system due to OOM (Out-of-Memory).

Other compression algorithms exhibit similar issues. Below is a list of compression ratios for compressing a 1GB file filled entirely with zeros using common algorithms:

2. Disk Exhaustion Attacks: Writing useless data to fill storage space. Prevent via disk quota management.

Common disk exhaustion attacks include:

1. Zip bombs. The attack method is identical to the "memory exhaustion attack" above, except the target program decompresses the zip file to disk rather than memory.

2. Low-cost or cost-free writing of large volumes of data to disk, exhausting disk capacity.

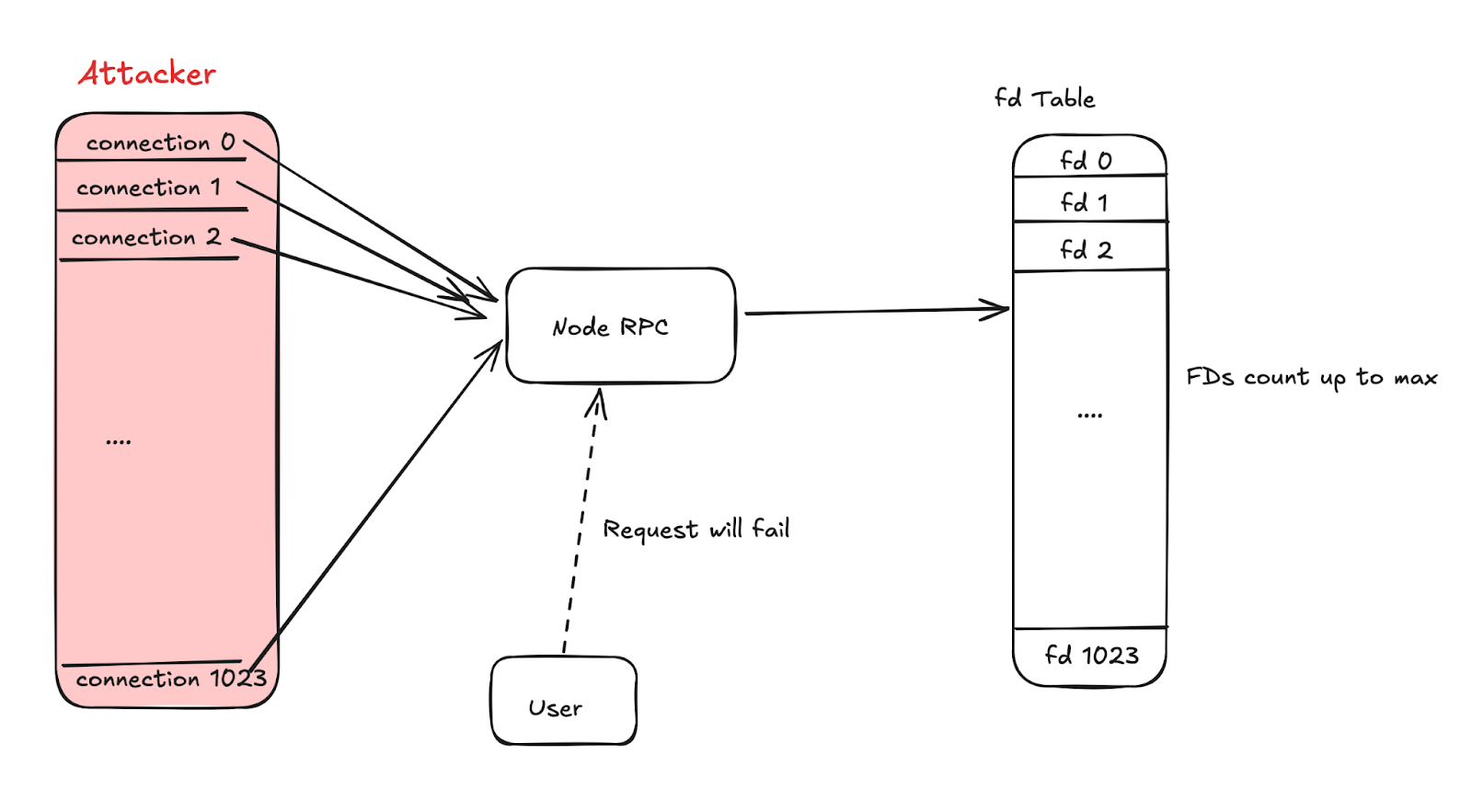

3. Kernel Handle Exhaustion Attacks: Excessive resource requests deplete kernel handles. Suggested countermeasures include controlling handle allocation and monitoring anomalies.

The general idea behind this attack is: An attacker exploits a vulnerability to exhaust or nearly exhaust a target node’s kernel handles, rendering it unable to respond to legitimate service requests.

A common variant is the "Socket Pressure Attack." If a target node does not limit connection count or concurrency, an attacker can send and maintain numerous connection requests, exhausting system socket resources.

4. Persistent Memory Leaks: Memory not properly released leads to resource depletion. Regular memory usage monitoring is required to prevent deterioration.

Memory leaks generally aren't considered security vulnerabilities unless attackers can repeatedly trigger them. Over time, cumulative memory consumption can cause the target node to crash due to insufficient memory.

1.7 Cryptographic Vulnerabilities

Cryptographic vulnerabilities compromise data confidentiality and integrity, posing potential security threats. Main types include:

Use of proven-insecure hash algorithms

Hash algorithms generate unique identifiers for data, ensuring integrity. Common algorithms like MD5 and SHA-1 have been proven vulnerable to collision attacks and exploitable by malicious actors. It is recommended to use more secure modern algorithms such as SHA-256 or SHA-3, keeping algorithms updated to avoid risks associated with outdated, crackable algorithms.

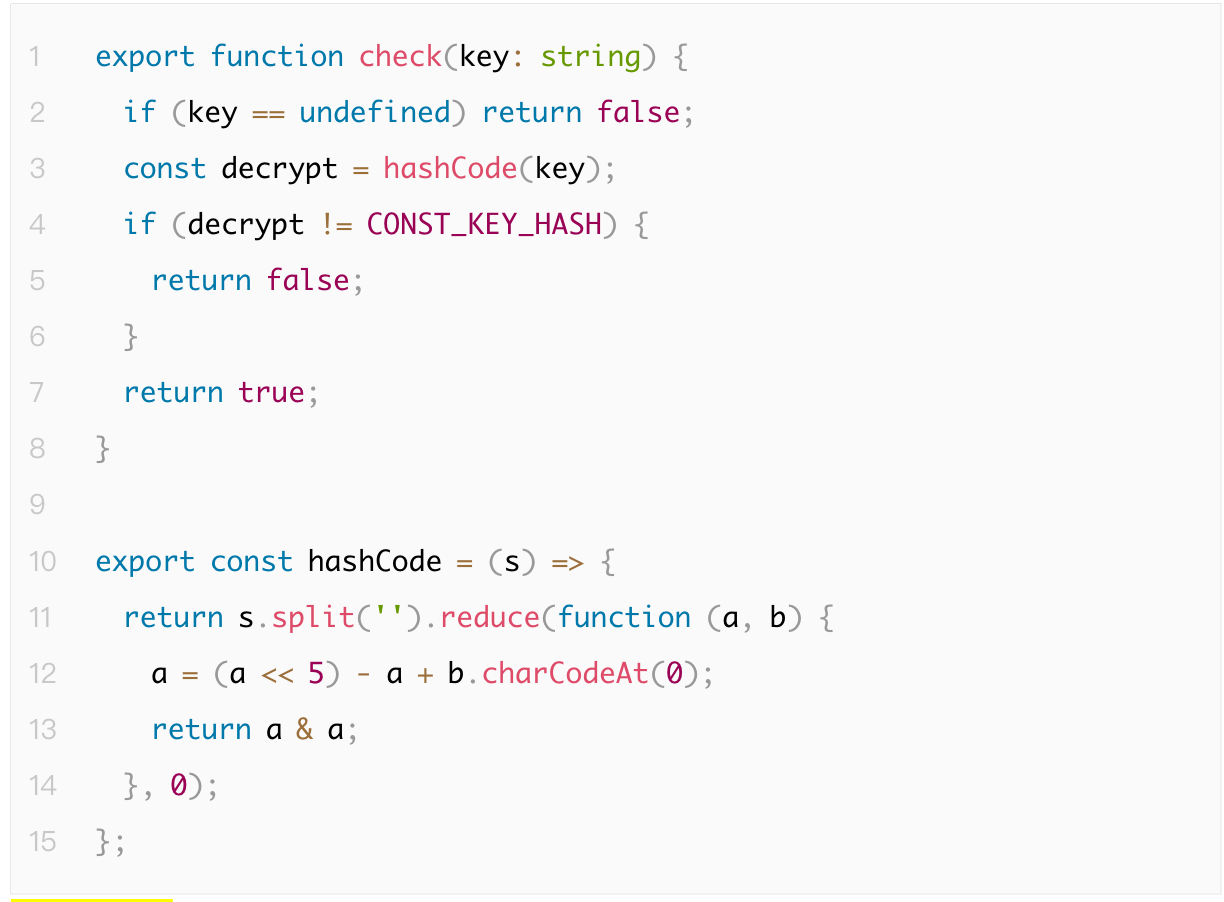

Use of insecure custom hash algorithms

Some projects use self-defined hash algorithms, which are generally less secure than well-known public algorithms.

For example, during audits, we encountered the following custom hash algorithm:

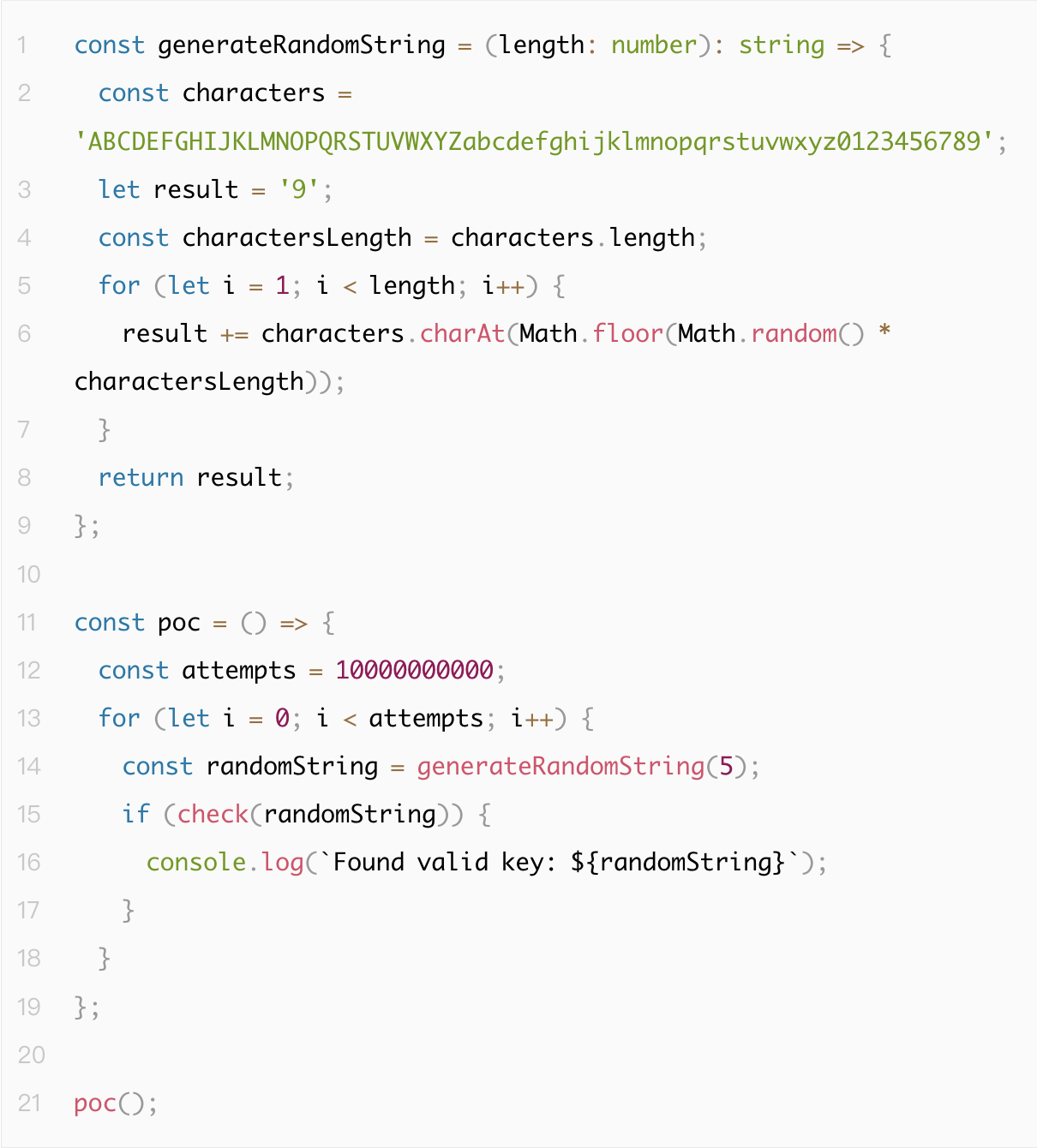

The `hashCode` function is not a cryptographic hash function and is highly prone to collisions. It performs only simple bitwise and addition operations. Moreover, its input-output length follows a predictable pattern, making it easily reversible and crackable. Due to this weak hashing mechanism, attackers can easily generate keys producing the same `CONST_KEY_HASH`, jeopardizing API authorization security.

Below is a proof-of-concept (PoC) demonstrating exploitation of this weak hash vulnerability:

Hash collisions caused by insecure usage

A common scenario is HASH(A+B+C)=HASH(D+E), occurring because A+B+C=D+E, although A, B, C, D, and E differ individually.

Use of insecure digital signature algorithms

Digital signature algorithms verify data authenticity and origin, preventing tampering. Early algorithms like DSA and RSA may become ineffective under quantum computing threats. Modern algorithms like ECDSA or EdDSA offer stronger security, protecting data legitimacy and anti-counterfeiting capabilities. Especially in distributed systems and smart contracts, ensuring signature algorithm reliability is crucial.

Use of insecure encryption algorithms

Encryption strength directly impacts data confidentiality. Weak algorithms like DES may be easily cracked. Use stronger symmetric encryption like AES-256 and implement end-to-end encryption (e.g., TLS) during communication to protect data in transit from eavesdropping or tampering. Also ensure proper key management to prevent leakage.

Use of insecure random number generation algorithms

Random number generators form the basis of many cryptographic operations, especially in generating keys, IVs (initialization vectors), and important parameters in asymmetric encryption. Ensuring unpredictability is critical. Common issues include:

1. Predictable or manipulatable random numbers due to insecure RNG algorithms;

2. Randomness in public chains is generally predictable because all information is transparent, making random numbers guessable;

3. Poor randomness increases the likelihood of certain vulnerabilities or issues (e.g., miner block production).

Use of insecure random number seeds

If random seeds are leaked or brute-forced, resulting in seed exposure, random numbers become predictable;

Cryptographic side-channel attacks

Side-channel attacks extract sensitive information by monitoring physical characteristics of the system (e.g., power consumption, execution time, cache). These bypass algorithm-level security and are particularly common in hardware devices and embedded systems. Defenses include optimizing algorithm implementations to maintain constant execution time and power usage, reducing leakable features. Techniques like masking and obfuscation can also reduce side-channel information leakage.

Signature Malleability

Signature malleability refers to deriving another valid signature from a known valid one without changing the signed content. A notable risk is transaction malleability, allowing malicious users to replay transactions using different signature variants. Since replays have different hashes, they confuse users' perception of transaction status during confirmation, enabling double-spending.

1.8 Ledger Security Vulnerabilities

Transaction mempool vulnerabilities

1. Transactions can be replayed

2. Failed transactions do not deduct fees

Block hash collision vulnerabilities

If block construction methods are flawed, collisions may occur.

Orphan block handling logic vulnerabilities

Orphan blocks can be discarded outright, but if cached, constraints such as height and timestamp must be added.

Merkle tree hash collision vulnerabilities

If Merkle tree leaf nodes are constructed improperly, collisions may occur.

Transaction amount handling issues

Caused by upper/lower bound overflows, type mismatches, precision errors, negative values, or unexpected values due to external changes during transaction amount processing.

Transaction fee handling issues

Caused by upper/lower bound overflows, type mismatches, precision errors, negative values, or unexpected values due to external changes during transaction fee processing.

Excessively sensitive time validation for block and transaction verification

Due to clock differences among nodes, time validation should not be overly strict, otherwise it may easily cause chain forks.

Transaction authorization logic issues

Mainly includes:

1. Identity forgery bypass

2. Permission check errors

1.9 Economic Model Vulnerabilities

Economic models play a vital role in blockchain and distributed systems, influencing network incentives, governance structures, and overall sustainability. Key considerations include:

Economic model of Cosmos application chains (e.g., UniChain)

Cosmos application chains adopt economic models centered on interoperability and scalability. Taking UniChain as an example, its economic design considers not only token circulation and usage but also diverse application needs. Leveraging the Cosmos SDK, UniChain creates application-specific blockchains and enables cross-chain communication, promoting resource sharing and value flow across chains. The economic model must address token issuance, inflation rates, transaction fee structures, and on-chain governance to ensure ecosystem stability and prosperity.

Reasonableness of incentive mechanisms

Incentive mechanisms are core to economic models, directly affecting participation by users and nodes. A reasonable incentive structure ensures fair rewards for all participants (miners, validators, developers, users). Sustainability of the incentive structure must be assessed to prevent malicious behavior and centralization trends. The mechanism should also adapt to market changes, adjusting as the network matures and user needs evolve. Questions such as whether appropriate reward and penalty mechanisms exist, and how short-term and long-term incentives are balanced, require in-depth analysis.

Network economic sustainability

Economic models must also consider long-term network sustainability, including economic incentives for ecosystem participants, value creation, and distribution management. Assessments should identify economic imbalances or resource waste, ensuring all participants receive fair value. External factors impacting network stability—such as market volatility and user behavior changes—should also be analyzed.

Market feedback mechanisms

Establish effective market feedback mechanisms so the economic model can adjust based on user demand and market dynamics. Regular data analysis and user feedback help promptly identify and correct potential issues, ensuring model flexibility and adaptability.

Impact of governance structure

Economic model design should integrate with governance structure, enabling users to participate in economic decisions, enhancing community engagement and belonging. Sound governance promotes self-correction and continuous optimization of the economic model, improving overall network health.

After gaining an in-depth understanding of various security vulnerability types present in the blockchain ecosystem, the next step is to explore the specific attack surfaces through which these vulnerabilities may be exploited. An attack surface refers to the entry points and pathways accessible to potential attackers. By identifying and analyzing these attack surfaces, risks can be more effectively assessed and corresponding protective strategies developed. Therefore, comprehensively understanding the relationship between vulnerabilities and attack surfaces is crucial for building a robust blockchain security defense. The following section details common attack surfaces in today’s blockchain ecosystem, helping readers better understand how threats are concretely realized.

2. List of Attack Surfaces

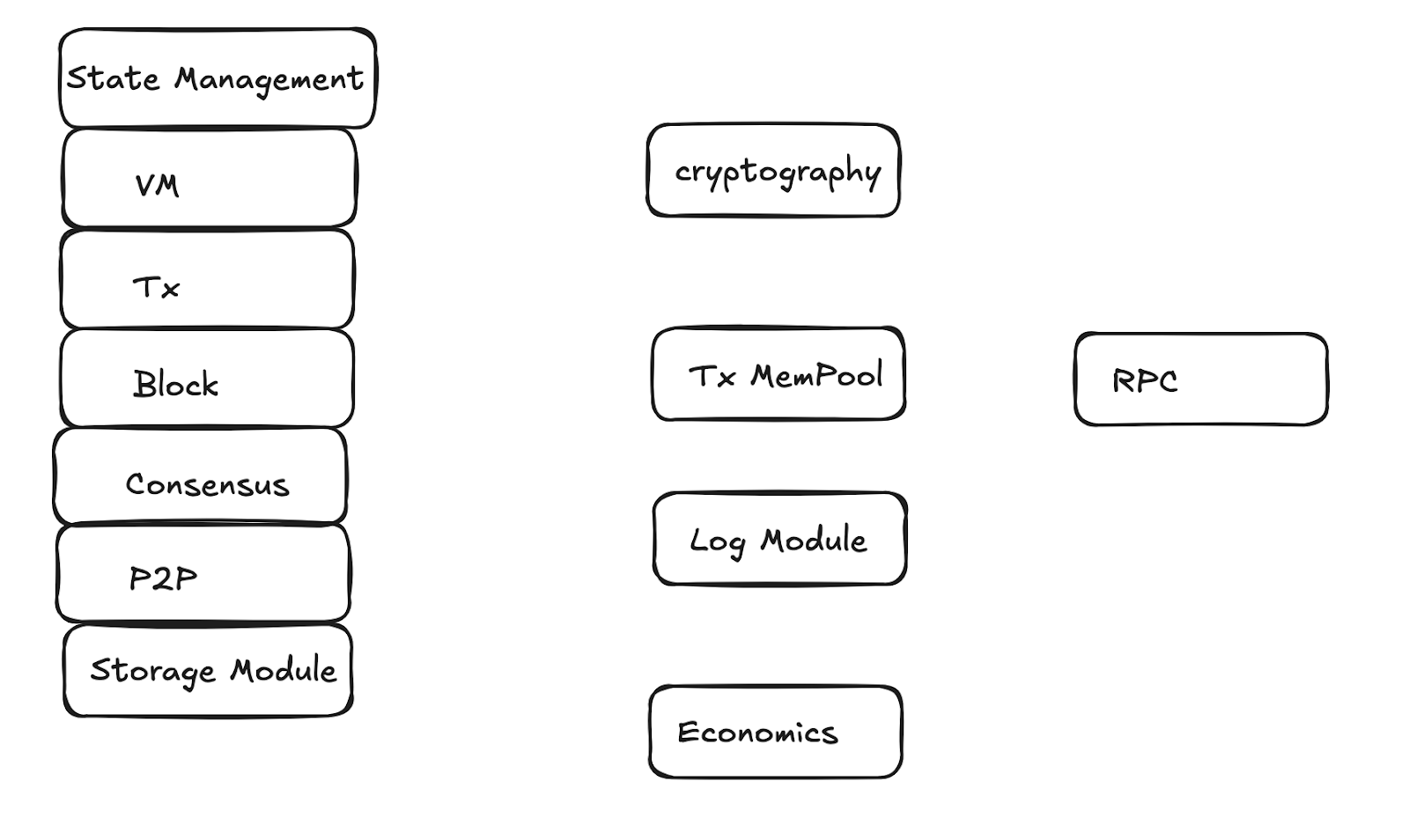

Below is a list of common attack surfaces:

4.1 Virtual Machine

Attack surface: The virtual machine executes smart contracts and processes bytecode, often handling complex logic, exposing risks such as reentrancy attacks, integer overflows, and memory overflows. Additionally, computationally intensive smart contracts may trigger DoS attacks, exhausting resources. Furthermore, bytecode containing unaudited vulnerabilities may lead to arbitrary code execution and privilege escalation.

4.2 P2P Node Discovery and Data Synchronization Module

Attack surface: Poorly designed P2P node discovery and synchronization functionalities are vulnerable to Sybil Attacks, where attackers forge numerous fake nodes to control the network, degrading or disabling network performance. Route table pollution during data synchronization affects peer connection quality, rendering some nodes unreachable. Additionally, packets may contain forged or malicious data, causing nodes to receive incorrect information, thereby affecting synchronization and consensus.

4.3 Block Parsing Module

Attack surface: Block parsing involves heavy data processing. If parsing code contains overflows or poor error handling, malicious blocks may trigger service crashes or denial-of-service (DoS). Moreover, incorrect block format validation may allow tampered blocks to go undetected during network transmission, affecting global consistency.

4.4 Transaction Parsing Module

Attack surface: Transaction parsing verifies transaction structure and signatures. Improper handling of forged transaction formats, malicious data, or abnormal signatures may allow fraudulent transactions to pass, consuming system resources. Boundary overflow issues in transaction parsing may also be exploited for memory injection attacks.

4.5 Transaction Mempool

Attack surface: The mempool serves as temporary storage before transactions enter the chain. It may be abused to insert numerous invalid or malicious transactions, causing memory consumption attacks that prevent nodes from responding to legitimate requests. Malicious actors may also flood the mempool with duplicate or high-frequency transactions, further causing resource exhaustion and DoS risks.

4.6 Consensus Protocol Module

Attack surface: Imperfectly designed or compromised consensus mechanisms may suffer double-spending attacks, selfish mining, or 51% attacks. Attackers controlling over half the computational power can execute malicious forks, undermining transaction legitimacy. Additionally, some consensus mechanisms may fail under high-latency or partitioned network conditions due to inadequate fault tolerance.

4.7 RPC Interface

Attack surface: The RPC interface enables external interaction with blockchain nodes. Improper access control configurations may lead to unauthorized access and data leaks. If privileged RPC interfaces are unprotected, attackers may forge requests to perform high-privilege operations, manipulating on-chain data. Additionally, RPC interfaces are susceptible to request flooding attacks, overloading node responses.

4.8 Log Processing Module

Attack surface: The log module records detailed system operation information. If attackers inject forged log content, sensitive information may be exposed. Excessive logging may also be exploited to cause log bloat, consuming storage resources or rendering the system unusable.

4.9 Network Middleware

Attack surface: Blockchain network communication middleware lacking encryption and authentication may suffer man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks, leading to packet interception and tampering. Additionally, middleware is vulnerable to traffic attacks (e.g., DoS) and protocol abuse, disrupting normal network communication.

4.10 Cryptographic Algorithms

Attack surface: The design and implementation of cryptographic algorithms directly impact data security. Hash collision vulnerabilities may allow forged transaction content; failure to follow strong randomness principles may lead to key exposure. Other common attacks include side-channel attacks, such as extracting sensitive information via power consumption or electromagnetic emissions during encryption execution.

4.11 Economic Models

Attack surface: Blockchain economic models must balance incentives among stakeholders. Otherwise, attackers may manipulate token circulation or reduce miner rewards to destabilize the system. Unreasonable incentive designs may cause miners (or validator nodes) to deviate from expected behavior, introducing economic attack risks.

4.12 Data Storage Module

Attack surface: On-chain and off-chain data storage faces risks of unauthorized access, tampering, and data persistence. Attackers may exploit insufficient database permissions or insecure storage mechanisms to directly modify ledger data or smart contract states. Additionally, poor data storage strategies may cause data bloat, degrading system performance.

4.13 State Management Module

Attack surface: Blockchain state management tracks critical data such as account balances and contract storage. Poorly designed state management modules may be exploited to cause incorrect account balances or altered state information. Malicious actors may also craft special transactions to achieve state hijacking, locking up resources.

Conclusion

In summary, while the blockchain ecosystem brims with innovation and developmental potential, its security challenges cannot be overlooked. This article has thoroughly examined security vulnerability types across key domains—from cross-chain communication, Cosmos application chains, and Bitcoin expansion ecosystems to programming language flaws, P2P network vulnerabilities, DoS attacks, cryptographic weaknesses, and ledger security. Through systematic analysis and summarization, we aim to help developers and security professionals identify potential risks and implement effective preventive measures to enhance overall security. Facing increasingly complex and diverse security challenges, only by continuously strengthening technical defenses, improving security audit mechanisms, and fostering industry collaboration and communication can we ensure the healthy and sustainable development of blockchain technology. ScaleBit and its parent company BitsLab will continue advancing blockchain security research, delivering forward-looking security solutions to contribute toward a more robust and trustworthy blockchain ecosystem.

Read and download the "2024 Panoramic Observation and Security Research Report on Emerging Public Chain Ecosystems": https://bitslab.xyz/reports-page

About ScaleBit

ScaleBit, a sub-brand under BitsLab, is a blockchain security team dedicated to providing security solutions for Web3 mass adoption. Leveraging professional expertise in blockchain scaling technologies such as cross-chain and zero-knowledge proofs, we specialize in delivering meticulous and cutting-edge security audits primarily for ZKP, Bitcoin Layer 2, and cross-chain applications.

The ScaleBit team comprises security experts with extensive experience in both academia and industry, committed to securing large-scale adoption within scalable blockchain ecosystems.

About BitsLab

BitsLab is a security organization dedicated to safeguarding and building emerging Web3 ecosystems, aspiring to become a highly respected Web3 security institution within the industry and among users. It operates three sub-brands: MoveBit, ScaleBit, and TonBit.

BitsLab focuses on infrastructure development and security auditing for emerging ecosystems, covering but not limited to Sui, Aptos, TON, Linea, BNB Chain, Soneium, Starknet, Movement, Monad, Internet Computer, and Solana. Additionally, BitsLab demonstrates deep expertise in auditing multiple programming languages, including Circom, Halo2, Move, Cairo, Tact, FunC, Vyper, and Solidity.

The BitsLab team brings together top-tier vulnerability researchers who have won multiple international CTF awards and discovered critical vulnerabilities in renowned projects such as TON, Aptos, Sui, Nervos, OKX, and Cosmos.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News