Is Blockchain Still Valuable? Finding Common Answers from the History of Automotive Industry Development

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Is Blockchain Still Valuable? Finding Common Answers from the History of Automotive Industry Development

Cryptocurrency will change the world in its unique way.

Author: Shlok Khemani & michaellwy

Translation: TechFlow

Today’s article offers entrepreneurs a framework for understanding the role of blockchain and its best-fit applications in solving problems and creating value. If you're a founder building a startup that uniquely benefits from crypto, we'd love to hear from you.

Hello!

Last week, the world was stunned by Mechazilla's successful capture of a booster rocket. This happened during an era when artificial intelligence has already captured global imagination. NVIDIA’s stock performance over recent months echoes the 2021 frenzy when companies rushed to add “blockchain” to their names. Yet this time, the hype is backed by real substance. As an industry, AI is attracting massive attention, capital, and talent.

In contrast, the blockchain (or crypto) industry seems lost in a jargon-filled mess, peppered with meme-like assets. It's hard not to feel that continuing to work in this space might be a waste of time. Of course, bull markets occasionally return, and price (or market sentiment) remains a key motivator for many to stay engaged. We may be on the frontier of the internet’s future evolution—or caught in a massive psychological experiment exploring what happens when individuals can turn anything into a market.

Possibly both.

This article, co-written with Monad's Michael, explores a critical question: Why does blockchain matter? Are these innovative systems as significant as space exploration or artificial intelligence? Are we wasting our time? To find answers, we look back at history—specifically, the automotive industry.

From Ford to Toyota

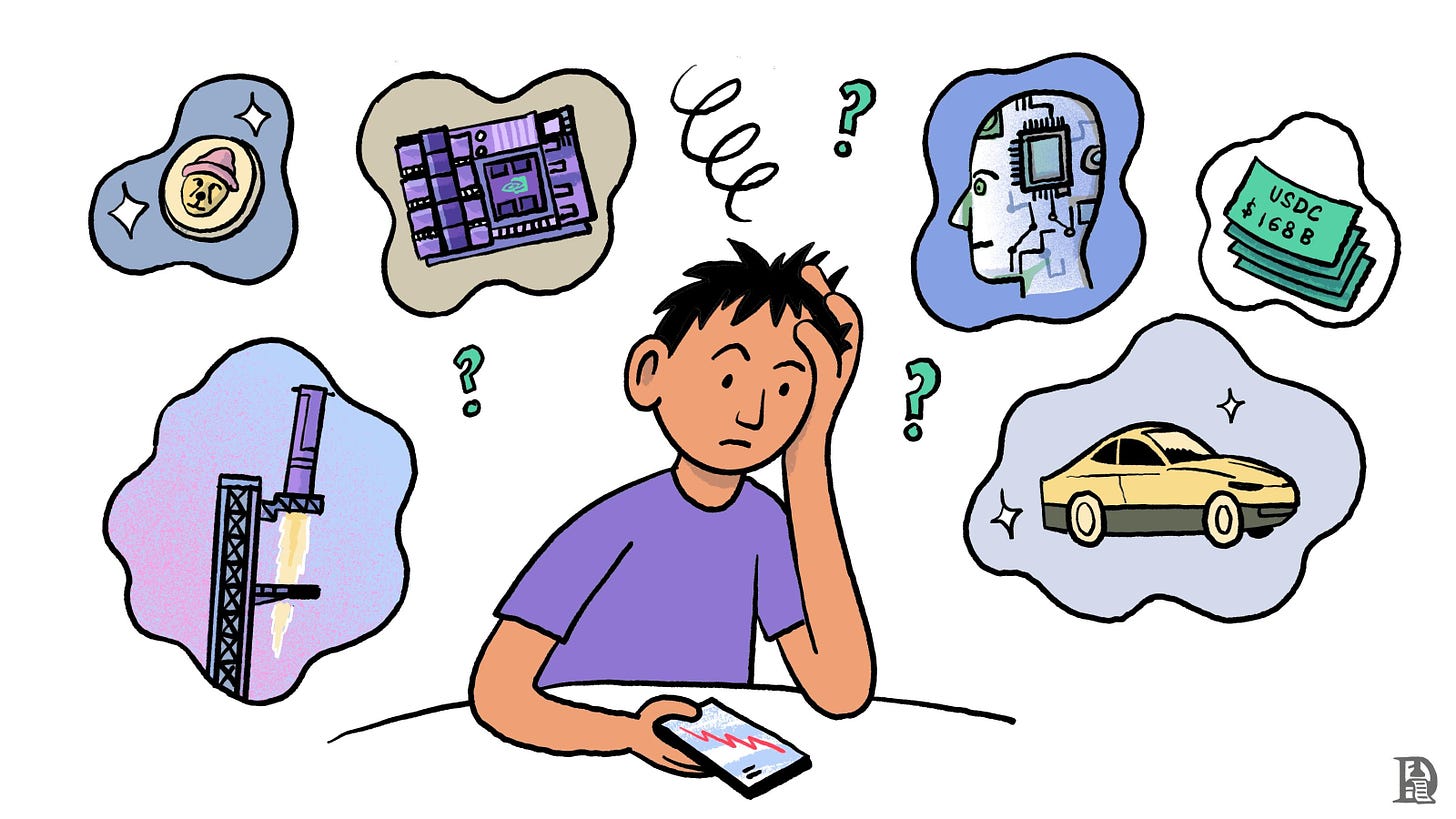

Before Henry Ford founded the Ford Motor Company in 1903, cars were luxury items accessible only to the wealthy. Vehicles were typically hand-built, resulting in low production efficiency and a scarcity of skilled labor. Ford’s breakthrough was the introduction of the moving assembly line, where each worker performed a specific task as the car moved past. By breaking down work into simple, repeatable actions, Ford could employ lower-skilled workers for many tasks. This dramatically increased productivity, reduced costs, and made automobiles affordable for the middle class.

Ford assembly line (source)

The mass adoption of automobiles transformed society in multiple ways. Horse-drawn carriages, once the primary mode of transport, were rapidly phased out. People could travel farther for work and leisure. Countless new jobs emerged—not just in auto manufacturing but also in related industries like rubber, steel, and oil. Roads reshaped geography, and modified Ford vehicles served as tractors, significantly boosting agricultural productivity.

Ford’s rise marked a defining turning point in human history.

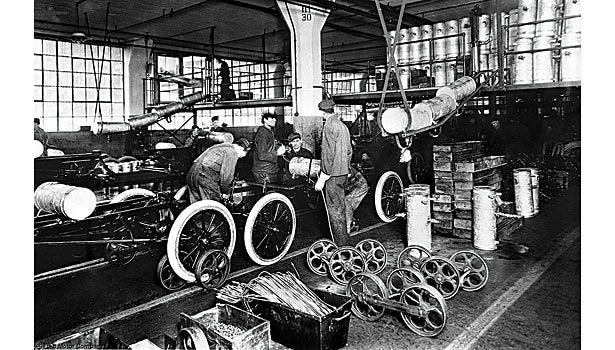

About 50 years later, after World War II, Japanese automaker Toyota was on the brink of bankruptcy. The government rejected its bailout request, 1,600 workers were laid off, and founder Kiichiro Toyoda resigned. The company survived only on U.S. military orders for vehicles during the Korean War. During this period, Eiji Toyoda (the founder’s cousin) and Taiichi Ohno reimagined how the automobile assembly line operated. Drawing inspiration from American supermarkets, they introduced systems such as just-in-time production, lean manufacturing, and kanban.

In Toyota factories, the Andon board lights up to alert workers of issues (source)

These improvements made Toyota’s manufacturing process more efficient, cost-effective, and higher in quality. A company once near collapse has grown into one of the world’s largest automakers, renowned for reliability.

Over time, the "Toyota Way" became an operational standard across the auto industry and beyond—from healthcare and retail to chip manufacturing and software development. While Toyota’s ascent was neither as swift nor as dramatic as Ford’s, it changed the world in a subtle, incremental, yet profound way.

Innovation comes in many forms.

The Schumpeterian view, derived from economist Joseph Schumpeter’s work, sees innovation as the primary engine of economic growth. Schumpeter introduced the concept of "creative destruction," describing how new technologies and innovations disrupt and replace outdated ones, thereby driving economic progress.

In simple terms, these breakthroughs greatly enhance human productivity and unlock vast latent economic value. Examples include Henry Ford’s assembly line, the printing press, microprocessors, the internet, and artificial intelligence.

In contrast, the Coasian perspective, rooted in economist Ronald Coase’s theories, emphasizes transaction costs and the role institutions play in reducing them to facilitate economic activity. Coase argued that economic systems and institutions exist primarily to minimize the costs of transactions and coordination between individuals and organizations.

The Coasian lens highlights less visible but equally important infrastructures that are crucial for improving economic efficiency. Although the economic benefits of refining institutional frameworks may not be immediately apparent, they are highly significant in the long run. Decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) are a prime example of Coasian innovation.

Toyota’s manufacturing innovations first transformed the company’s fate, then reshaped the economic landscape of the auto industry, and ultimately influenced countless other sectors. However, this transformation occurred gradually, with its impact becoming clear only in hindsight rather than during the transition itself.

Other examples—such as double-entry bookkeeping, stock exchanges, open-source software, and reusable rocket boosters—are instances of technological progress driven by Coasian logic. While these innovations may lack the drama of Schumpeterian breakthroughs, they are equally vital in enhancing economic efficiency and advancing human society.

So what about cryptocurrency?

Consider the areas where crypto has already found or is approaching product-market fit.

First, Bitcoin has evolved into a trillion-dollar asset and established itself as a legitimate, institutionalized store of value. Bitcoin possesses most of gold’s key properties—scarcity, durability, portability, divisibility, and inertness. Time will tell whether it can surpass gold as the de facto store of value. If so, it will be because it implements these properties more efficiently. Bitcoin even has its own ETFs—evidence that Wall Street views it as an asset worth watching.

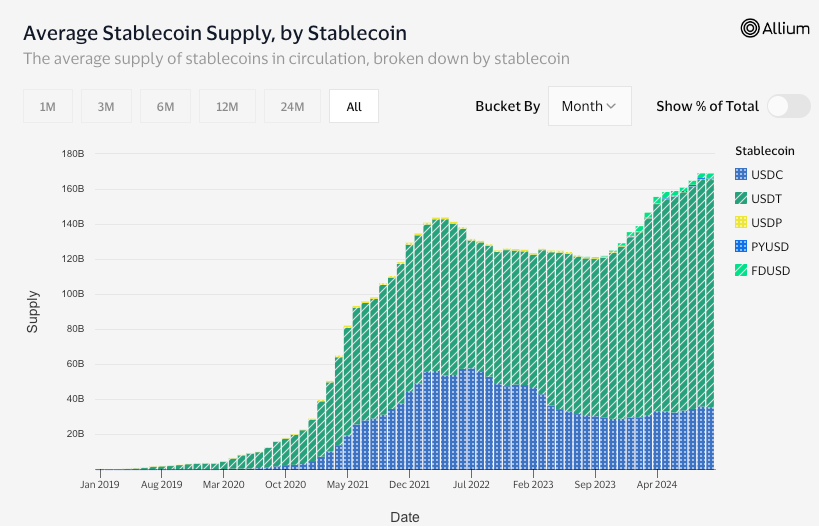

Next, stablecoins offer a cheaper and faster alternative for cross-border payments compared to traditional methods. Demand is strong—the total supply of stablecoins has grown from $500 million to $168 billion, demonstrating clear market validation.

It’s worth asking why this is happening. Cross-border fiat transfers usually involve multiple intermediaries—banks, governments, and services like Western Union. Each intermediary exists to provide trust, and thus charges fees (in money or time). Blockchain, as a highly secure, transparent, and decentralized ledger, drastically reduces the cost of trust. Stablecoins are cheaper and faster because the trust provided by the Ethereum blockchain rivals—and in some cases exceeds—that offered by the constellation of institutions underpinning traditional fiat systems.

The same principle applies in areas like decentralized finance (DeFi) and digital art (NFTs). In DeFi, interacting with smart contracts is more efficient than transacting through intermediaries like banks, brokers, and exchanges. Before NFTs, auction houses served as the trust bridge between collectors and artists. Unknown artists struggled to sell works at high prices without an auction house’s endorsement. Ethereum provides equivalent—or even superior—trust guarantees, and does so faster and more affordably.

Recently, we’ve seen the rise of various DePIN networks. Are these creating entirely new services? Not really. Mobile data, electricity, GPUs, satellite data, and digital maps don’t depend on blockchain to exist. But their monetization and distribution are either inefficient or reliant on centralized entities. DePIN networks aim to enable more efficient coordination.

At its core, cryptocurrency is a Coasian technology. While crypto has brought revolutionary changes from a financial standpoint, viewed more broadly, finance itself is a mechanism for enabling human coordination and productivity—and finance inherently carries Coasian characteristics.

Crypto won’t change the world in the same way as AI or rockets—it was never meant to. Instead, it plays a different role. It will help us collect data to train large language models (LLMs), and provide a means for value transfer between AI agents. It will accelerate the formation of new networks and might even help the next Elon Musk migrate from a developing country to the United States. But crypto alone may not upend societal structures as dramatically as we once imagined. It’s more like paint than canvas—the picture it will create remains to be seen.

As technology advances along exponential trajectories, crypto will lubricate the wheels of progress, pave the roads for innovation, and strengthen the bridges of connection.

Crypto will change the world in its own unique way.

Enjoying the Ethereum vs Solana debates on CT,

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News