Web3 Gaming Analysis Series (2): Industrialized Production and Creation (Technology and Art)

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Web3 Gaming Analysis Series (2): Industrialized Production and Creation (Technology and Art)

This article primarily analyzes the industrial production and development (art and technology) of Web3 gaming.

Author: Jake @Antalpha Ventures, Blake @Akedo Games, Jawker @Cipherwave Capital

Introduction

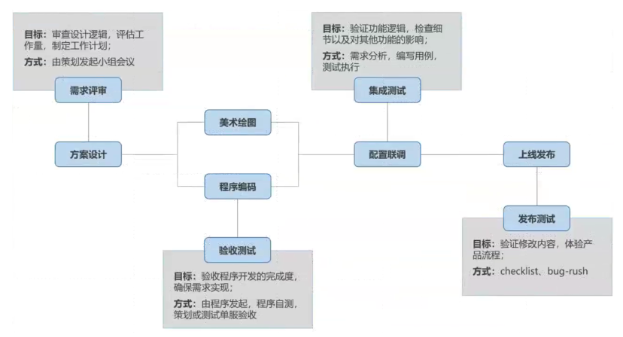

Due to differences in architecture adopted by various development companies—such as project-centric versus platform-centered organizational structures—the emphasis on projects and central platforms varies. Some organizations prioritize strong project teams with a weaker central platform, while others emphasize a robust central platform with relatively weaker individual projects. Therefore, this series primarily analyzes aspects based on functions and processes involved in game development. Accordingly, this second article focuses on the industrialized production and creation of Web3 gaming, particularly in art and technology. After a game project is greenlit, designers finalize core gameplay mechanics and playability details such as character progression, player behavior guidance, maps, and storylines. At this stage, game designers must collaborate with art and technical teams to advance the Web3 game into its design and development phase.

Source: Public market information

Source: Buming Technology

Industrialized Production & Creation: Technical Overview

Once design requirements are clarified, frontend and backend technical teams implement the game designs proposed by the design department by writing code to ensure technical feasibility. Execution can be divided into frontend and backend programming. The lead programmer oversees the entire technical process, including determining primary implementation strategies, performance optimization, and guiding the construction of underlying frameworks.

-

Frontend Programming: Covers display, optimization, and logic-related tasks, including processing audio files, image files, and text files.

-

Backend Programming: Covers server-side operations, including database structure, data transmission, validation, storage, communication protocols, etc.

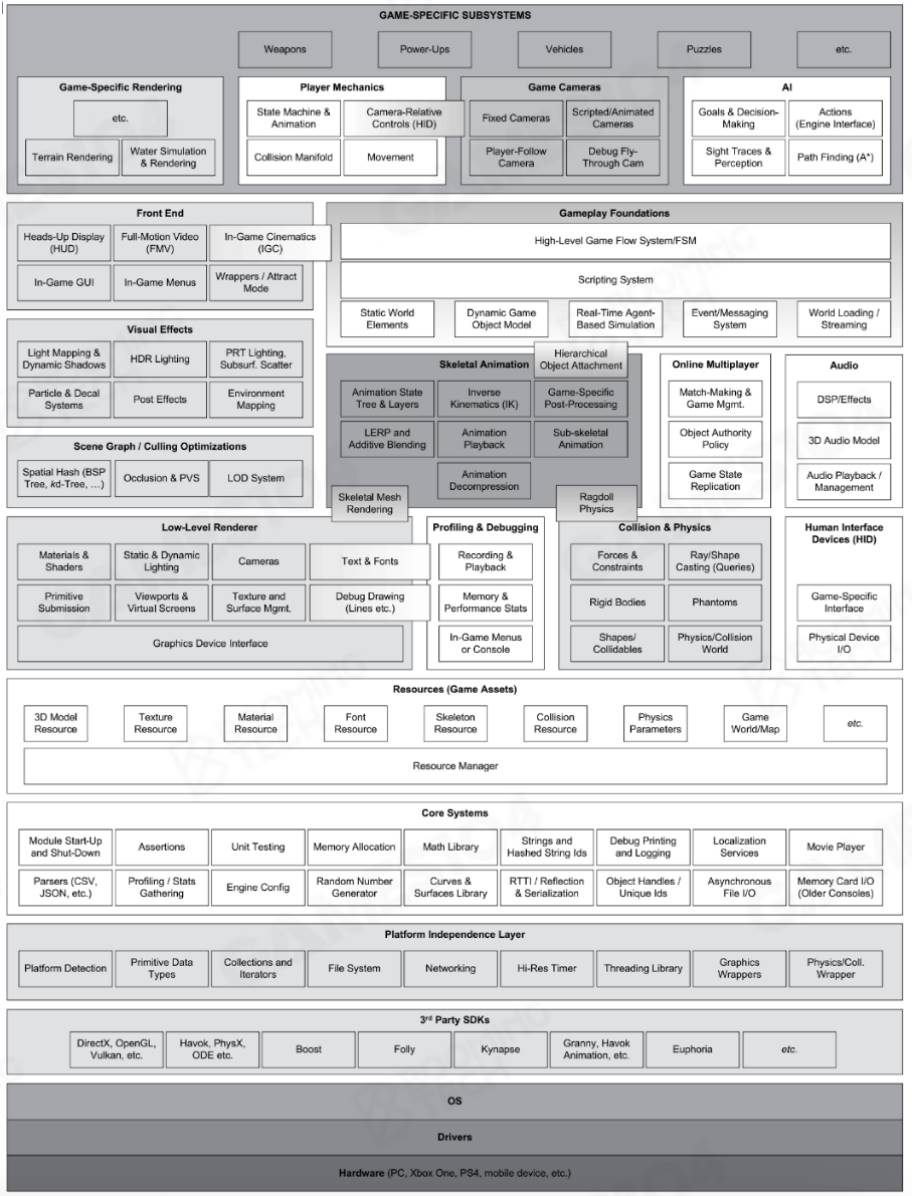

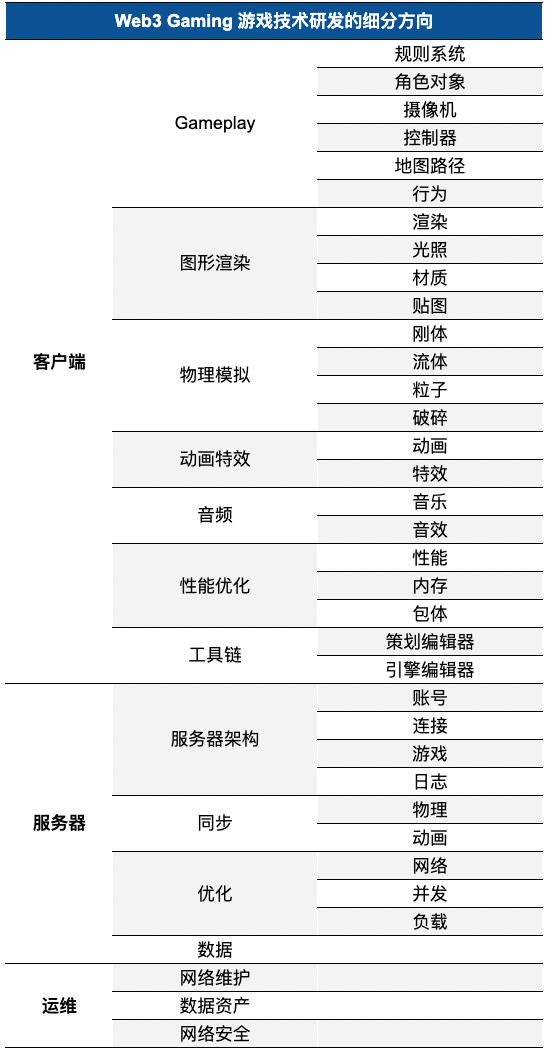

The diagram below illustrates components of frontend and backend programming in Web3 gaming. Both parts will be analyzed in detail later.

Source: YouSha Game Circle; compiled by Jake

Industrialized Production & Creation: Frontend Technology

Frontend game development focuses on user interface, interaction, and user experience. In terms of interactivity and UX, special attention should be paid to UI design and implementation, user interaction (UI) system development, and animation and visual effects creation. Additionally, frontend engineers must ensure consistent user experiences across different platforms, including desktop and mobile devices. Regarding game logic implementation, developers need to manage character behaviors, execution of game rules, score and progress tracking, and in-game event response mechanisms. Efficient and seamless code ensures smooth, fair, and challenging gameplay.

To achieve these goals, frontend developers use programming languages such as C#, C++, and game engines like Unreal, Unity, Source, and CryEngine to create interfaces, adjust animations, and refine sound effects. Numerous game engine tools are available, and selection depends on specific developer needs. Different engines offer varying levels of community support. Below are key considerations influencing engine selection in game R&D:

-

Project Requirements: Different game types demand different engines. For visually intensive AAA titles, Unreal Engine or CryEngine may be more suitable; for small-scale mobile games, Unity might be preferable.

-

Learning Curve & Community Support: An easy-to-learn engine significantly reduces development difficulty. Active communities provide abundant resources, enabling rapid problem-solving when issues arise.

-

Performance & Optimization: Engine performance and optimization capabilities are crucial for smooth gameplay.

-

Cost & Licensing: Some engines require payment or have specific licensing terms. Developers must balance budget constraints against project demands.

-

Scalability & Customizability: As the industry evolves, game engines must adapt to new technological trends. Understanding an engine’s scalability and customization potential helps developers prepare for future changes.

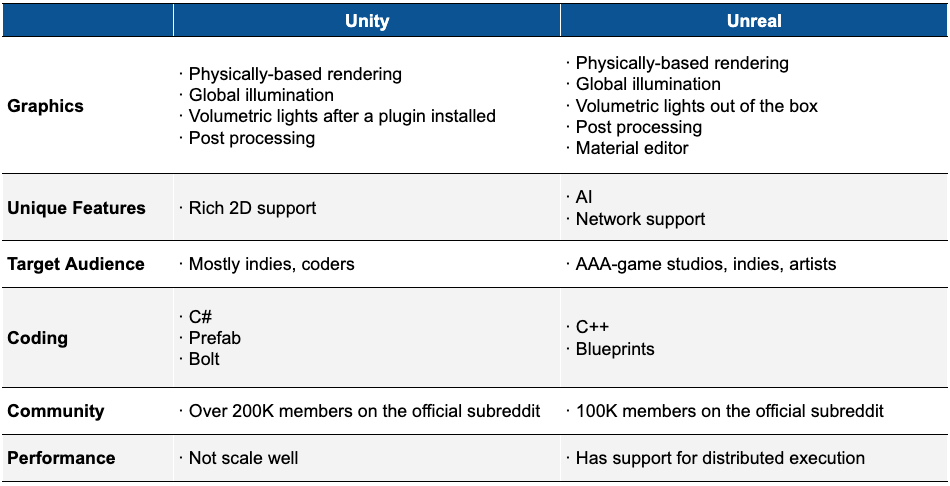

Based on the above analysis, here's a brief introduction and comparison of two representative game engines: Unity and Unreal Engine.

-

Unity is a multi-platform game engine supporting major systems such as Windows, Mac, iOS, and Android. It offers high customizability, allowing developers to write scripts using

C#orJavaScript. Unity also provides a rich asset store where developers can purchase or download plugins, models, and sound effects. Key advantages include an active community, excellent cross-platform compatibility, beginner-friendly development environment, and extensive third-party packages. Developers can even publish their own functional packages on Unity’s official store for sale. Currently, over 1.5 million developers browse the store monthly, with more than 56,000 available packages. From a commercialization perspective, Unity offers diversified monetization channels, including Monetization SDK, Unity Game Cloud services, Vivox voice chat, Multiplay overseas server hosting, Unity Distribution Platform (UDP), and Unity Cloud Build. Among them, the Monetization SDK allows Unity to act directly as an ad distribution gateway, which has now replaced engine licensing fees as Unity’s primary revenue source. Globally renowned games such as Escape from Tarkov, Temtem, Call of Duty Mobile, and Hearthstone demonstrate Unity’s status as one of the top game engines. However, Unity’s performance optimization lags behind competitors, especially in handling large-scale scenes and high-precision models. Its UI experience is inferior to Unreal, often requiring third-party packages to enhance functionality. Additionally, Unity’s use ofC#andJavaScriptintroduces some adaptation challenges during development. In March 2020, Unity officially launched version2019.3, introducing High Definition Render Pipeline (HDRP) and Universal Render Pipeline (URP), enhancing visual fidelity and optimization. Features like the Shader Graph editor and real-time ray tracing further align Unity with current market demands and enable it for large-scale game production. -

Unreal Engine is a fully open-source, high-performance game engine known for its outstanding graphics and physics simulation. It supports C++ and Blueprint visual scripting, offering powerful material editors and lighting systems capable of producing photorealistic visuals. For developers, Unreal is free to use and allows access to source code, improving development efficiency. The built-in Blueprint system enables non-programmers to design games via visual interfaces. Moreover, Unreal boasts cross-platform compatibility and a highly customizable UI system. Revenue models include a traditional approach: a fixed 5% royalty on game revenue exceeding $1 million, or a 12% cut from assets sold in the marketplace (either official or third-party). Notable titles such as Borderlands, Batman: Arkham Asylum, and Final Fantasy VII Remake utilize Unreal Engine. However, Unreal has a steep learning curve—easy to start but difficult to master—requiring time and experience to fully leverage its capabilities.

According to data analysis from Medium and Jingke, Unity held a global market share of 49.5% in 2021, compared to Unreal’s 9.7%, forming a duopoly. Another report shows that in 2023, Unity and Unreal Engine had market shares of 48% and 13%, respectively. The table below compares both engines across graphics, features, code, and performance.

Source: Incredibuild; Jake’s comprehensive analysis

In visual and graphical output, Unreal Engine slightly outperforms Unity, though the gap is minimal. From a usability standpoint, Unity is easier for beginners, with C# enabling faster compilation and shorter iteration cycles. Conversely, Unreal Engine poses greater challenges for newcomers in animation and graphics processing. Practically speaking, any effect achievable in Unreal can also be realized in Unity. Both engines can enhance graphical performance through API calls or external tools. Statistically, software engineers tend to prefer Unity, whereas technical artists who prioritize graphics and expression favor Unreal Engine.

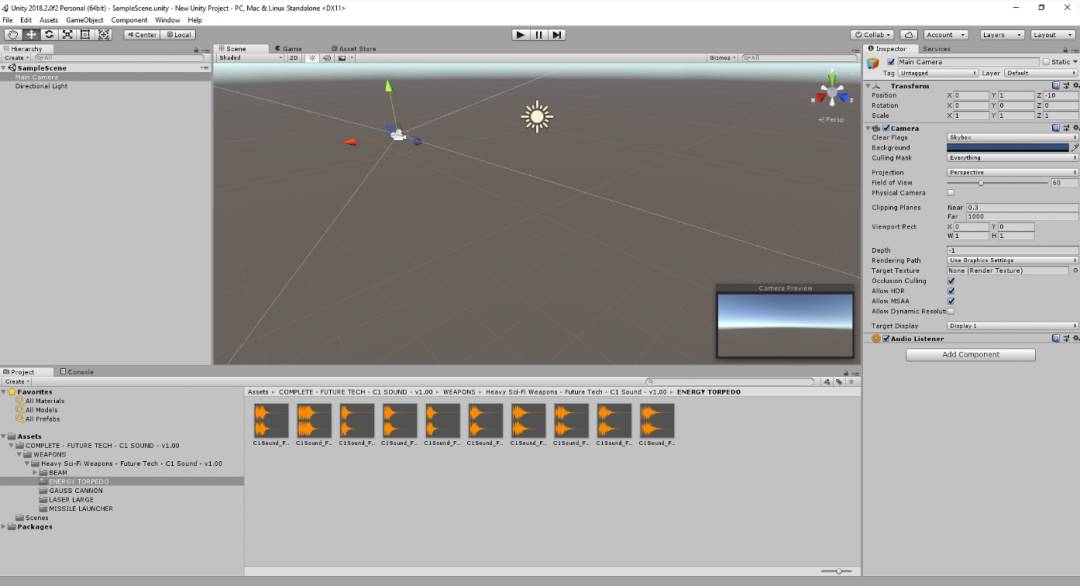

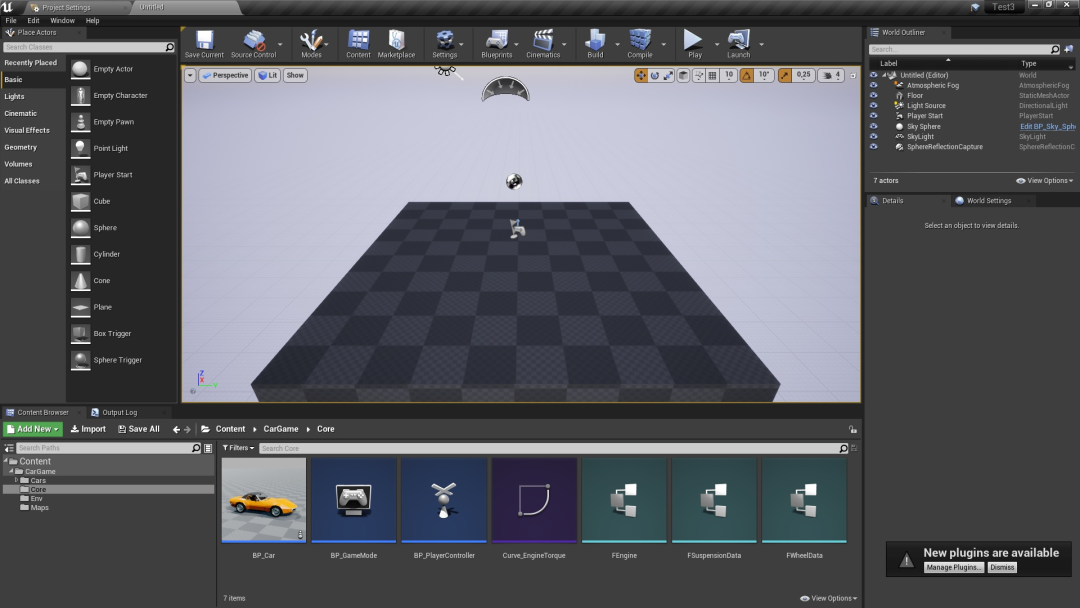

Unity Interface Demo, Source: Public market information

Unreal Engine Interface Demo, Source: Public market information

Besides Unity and Unreal, other game engines are available for frontend developers:

-

CryEngine is known for high-quality visuals and powerful physics simulation. It supports real-time global illumination and high-fidelity models and materials, enabling developers to create world-class realistic games. However, CryEngine suffers from limited documentation and community resources, posing learning difficulties for beginners.

-

GameMaker Studio 2 is a development tool for creating 2D or 3D games. It includes numerous tools and editors to help realize game ideas and deploy projects across multiple platforms from a common base. GameMaker Studio 2 features an intuitive drag-and-drop (DnD™) action interface, allowing virtual logic creation without coding. Alternatively, developers can use the GML scripting language, or combine both approaches by calling functions within DnD™ actions.

-

Godot Engine is a versatile, cross-platform open-source engine supporting 2D and 3D development, running on Windows, macOS, Linux, and deploying to PC, Android, iOS, HTML5, and more. Using a node-based architecture, its 3D renderer enhances visual quality, while built-in 2D tools operate at pixel coordinates for precise control over 2D effects.

Regardless of the chosen engine, frontend developers must consider practical usage scenarios. Since Web3 games are consumer products, diverse gameplay mechanics (e.g., focus, empathy, imagination) and immersive emotional interactions (e.g., joy, fear, desire, growth, relaxation, surprise) are essential prerequisites for sustained consumer engagement. The following section uses physics simulation and rendering systems as examples to analyze technical considerations and user experience issues frontend developers face when using game engines.

Without accurate physical simulation, even the most visually impressive games appear static and lifeless. Diverse in-game environments rely heavily on physics principles and engines. A physics engine is a component that assigns real-world physical properties (e.g., weight, shape) to in-game objects, abstracting them into rigid body models (including pulleys, ropes, etc.), simulating motion and collision under forces according to Newtonian mechanics. Through simple APIs, it calculates object movement, rotation, and collisions, replicating real-world dynamics. This involves theories and computations from kinematics and dynamics.

-

Kinematics: A branch of mechanics that describes and studies how object positions change over time purely from a geometric perspective, without considering the physical properties of objects or applied forces. Point kinematics examines motion equations, trajectories, displacement, velocity, acceleration, and spatial transformations. As a subfield of theoretical mechanics, it applies geometric methods to study motion. During development, frontend engineers must introduce simplifying assumptions—balancing realism with reduced computational complexity. Common assumptions include ignoring external forces, treating objects as geometric entities modeled as point masses, and focusing only on attributes like position, velocity, and angle.

-

Dynamics: Focuses on the relationship between forces acting on objects and their resulting motion. Dynamics primarily studies macroscopic objects moving much slower than light speed. In game physics engines, rigid body dynamics dominate, involving fundamental theorems such as momentum, angular momentum, kinetic energy, and derived principles. Momentum, angular momentum, and kinetic energy are key physical quantities describing particle systems and rigid bodies. During work and computation, factors and assumptions include the impact of external forces on motion, force applications (gravity, resistance, friction affecting mass and shape, including elastic bodies), rigid body assumptions, and ensuring in-game motion closely mimics real-world behavior.

With a physics engine, developers only need to assign shapes (assumed uniformly distributed) and forces to objects—the engine automatically handles motion and collision calculations. Based on this analysis, frontend teams don’t need to delve deeply into complex kinematic knowledge or collision optimization—they simply input parameters into the physics engine. However, to efficiently utilize the engine, teams must understand basic physical motion concepts and recognize unique phenomena arising from discrete simulations to avoid distortions. Experienced frontend engineers must also consider game fluidity and runtime performance.

Before building rigid body motion models, several factors must be considered:

-

Whether the model is rigid and its degree of elastic deformation under force;

-

Whether shape and size change during motion or after force application;

-

Whether relative positions of internal points within the object change during motion or after force application;

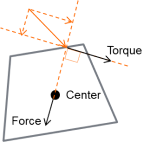

Therefore, based on the above, frontend technical teams must define the object’s center, shape, mass, initial direction, and trajectory. Regarding gravity and motion, particular attention should be paid to setting the center of mass, assuming uniform density with center coinciding with center of mass. When defining motion, forces acting on the object should be decomposed into linear force at the center and torque around the center. Parameter settings must align with players’ expectations of object behavior to maintain immersion—otherwise, inconsistencies break player engagement. The diagram below illustrates force and torque decomposition:

Source: Public market information

To achieve realistic physical behavior, in-game objects must accelerate correctly (aligned with human perception) and respond appropriately to collisions, gravity, and other forces. First, when setting up 3D object motion, determine whether the model is convex—that is, any line drawn between two vertices does not exit the object’s surface. Although most real-world objects aren't convex, convex shapes serve as ideal approximations in physics simulation. Physics engines generate more accurate passive behaviors (like collisions and falls) with convex shapes, striking a balance between primitive and concave collision shapes, capable of representing any complex form. Script-controlled physics can give objects dynamic properties like vehicles, machines, or cloth. Input meshes can be concave—the engine computes their convex parts. Depending on object complexity, using multiple convex shapes often yields better performance than single concave collision shapes. Godot allows generating approximate convex shapes matching hollow objects via convex decomposition, though performance gains diminish with excessive convex elements. For large, complex objects like entire levels, concave shapes are recommended. Common shape types used in modeling include sphere (SPHERE), box (BOX), capsule (CAPSULE), cylinder (CYLINDER), and convex hull (CONVEX_HULL), with adjustable parameters like center, rotation, and dimensions for frontend use.

Simulating object motion requires additional computation. Adding a physics engine upon importing models may fail, so wrapping the object with a simple mesh whose pose follows the mesh is advisable. Meshes created in Babylon can directly receive physics properties or custom shaders for enhanced results. While custom shaders are complex, they deliver superior outcomes. In the editor, selecting a mesh instance and using the Mesh menu at the top of the 3D viewport generates one or more convex collision shapes. Two generation modes are provided:

-

Create Single Convex Collision uses the

Quickhullalgorithm to generate one CollisionShape node with an auto-generated convex shape. With only one shape generated, performance is optimal, ideal for small object models. -

Create Multiple Convex Collision Siblings uses the

V-HACDalgorithm to generate several CollisionShape nodes, each with a convex shape. Though less performant due to multiple shapes, it offers higher accuracy for concave objects. For moderately complex objects, it may outperform a single concave collision shape.

For concave collision shapes, concave forms are the slowest option but most accurate in Godot. They can only be used in StaticBodies and cannot interact with KinematicBodies or RigidBodies unless the latter are set to static mode. When GridMaps aren’t used for level design, concave shapes are optimal for level collision detection. Alternatively, build a simplified collision mesh in a 3D modeling tool and let Godot automatically generate collision shapes. In the editor, select MeshInstance and use the Mesh menu at the top of the 3D viewport to generate concave collision shapes. Two options are available:

-

Create Trimesh Static Body creates a StaticBody containing a concave shape matching the mesh geometry.

-

Create Trimesh Collision Sibling creates a CollisionShape node whose concave shape matches the mesh geometry.

Note: To improve performance, keep the number of shapes as low as possible, especially for dynamic objects like RigidBodies and KinematicBodies. Avoid translating, rotating, or scaling CollisionShapes to benefit from internal physics engine optimizations. When using a single untransformed collision shape in a StaticBody, the engine’s broad-phase algorithm can discard inactive PhysicsBodies. If performance issues occur, trade-offs between accuracy and performance are necessary. Most games do not feature 100% accurate collisions—creative solutions hide inaccuracies or make them imperceptible during normal gameplay.

Source: Public market information

The above discusses physics simulation as a case study of frontend development responsibilities. Next, we examine the rendering system (rendering engine/renderer) as another example of frontend development tasks. The rendering system is among the most advanced and challenging components of a game engine. Theoretically, rendering must address two main aspects: mathematical correctness (accuracy in math, physics, and algorithms) and visual fidelity (accuracy in lighting, depth, scattering, refraction, reflection, etc.) to immerse users. Practically, four key challenges must be addressed:

-

Scene Complexity: Rendering multiple objects from various angles within a single scene requires repeated calculations per frame; complexity increases significantly across multiple scenes.

-

Hardware Deep Adaptation: Hardware capabilities (PCs, phones, etc.) affect algorithm execution and output. Developers must handle time-consuming texture sampling and complex mathematical operations (e.g., sine, cosine, exponentials, logarithms). Additionally, hardware support for mixed-precision computing is critical for deep hardware optimization.

-

Performance Budget: Regardless of graphical demands, the engine must complete each frame within 33 milliseconds (1/30 second). In deeply immersive games, significant visual changes may occur quickly, yet calculation time cannot decrease. As the industry advances, demands for finer details, higher frame rates, and resolution increase—leaving fewer milliseconds per frame while simultaneously demanding higher image quality.

-

Frame Time Budget Allocation: GPU usage should outweigh CPU usage. Rendering algorithms must not consume excessive CPU resources, which must be allocated to other system modules.

Source: Buming Technology

As analyzed above, computation is one of the core functions of rendering systems—executing operations across millions of vertices, pixels, logical units, and textures. Simply put, in practice, multiple planes constructed from triangles undergo projection matrices and are projected onto screen space. Rasterization converts vertex data into fragments, where each fragment element corresponds to a pixel in the framebuffer, transforming geometry into a rasterized 2D image. During shading and rendering, each pixel computes corresponding material and texture values, rendering the pixel color. To enhance immersion and realism, lighting and surface patterns must be adjusted accordingly before final rendering. Once vertex and index buffers are prepared, mesh data is transferred to the GPU. The entire process—projection → rasterization → shading/rendering → post-processing/lighting computation—is the essence of rendering.

Source: Buming Technology

In detail, rendered objects and scenes possess diverse geometries, materials, textures, and application contexts, requiring tailored rendering approaches. Typically, model files contain multiple vertices storing position, normal direction, UV coordinates, and other attributes. Usually, triangle orientations are calculated per model, and vertex normals are derived by averaging adjacent triangle normals. In practice, triangle descriptions use indexed and vertex data—storing all vertices in an array and referencing only three vertex indices—reducing storage to roughly 1/6 of original size.

Textures are a vital means of expressing material. Perception of material type is often determined not by parameters but by texture—for example, distinguishing polished metal from rusty non-metal surfaces relies on roughness maps. Shading and rendering involve heavy and complex texture sampling: one sample accesses 2×4=8 pixels and requires seven interpolation operations. Crucially, sampling must prevent aliasing artifacts like flickering or misalignment caused by viewpoint changes. Thus, four-point sampling with interpolation and proportional sampling across two texture layers are essential.

During shading and rendering, various elements are combined. The engine-generated Shader code is compiled into binary blocks (Blocks), stored alongside network data. Diverse combinations of meshes and Shader code form rich game worlds. Different materials on the same model can use separate materials, textures, and Shaders within respective sub-meshes. Since each sub-mesh uses partial data, only starting and ending offset indices in the index buffer need storing. Also, shared resource pools (e.g., mesh pool, texture pool) save space. Notably, instanced rendering shares vertex data, greatly reducing VRAM usage and bandwidth. For high-demand games, additional technical adjustments (e.g., individual object selection) may be needed during instancing.

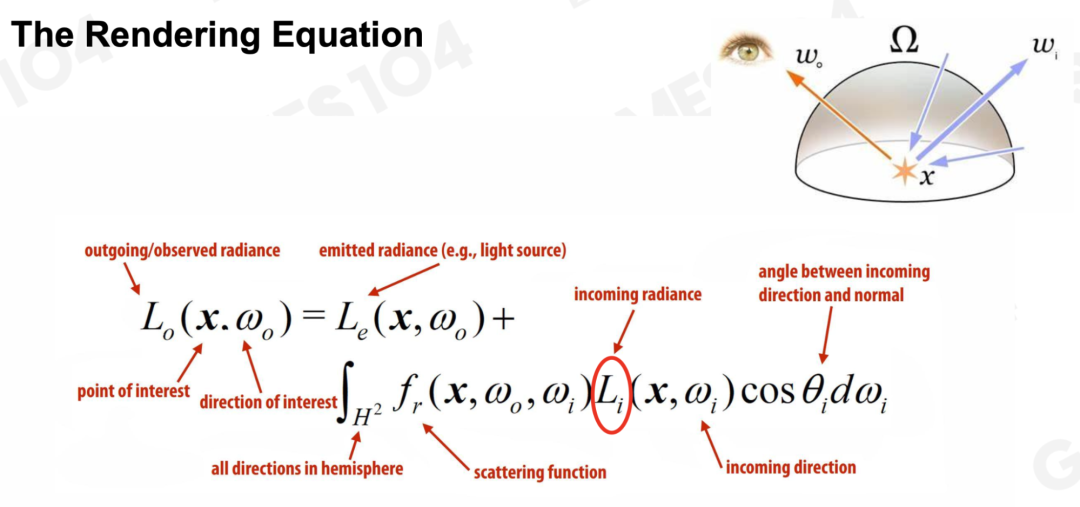

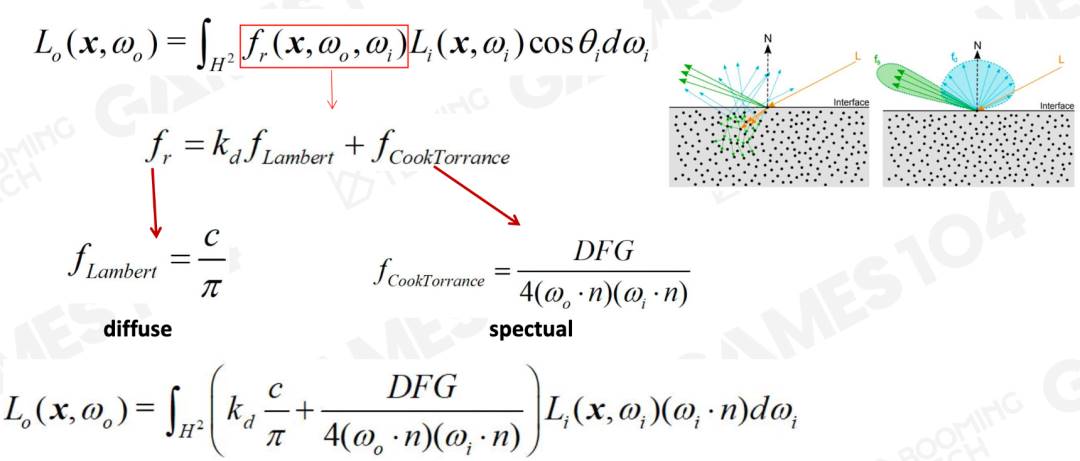

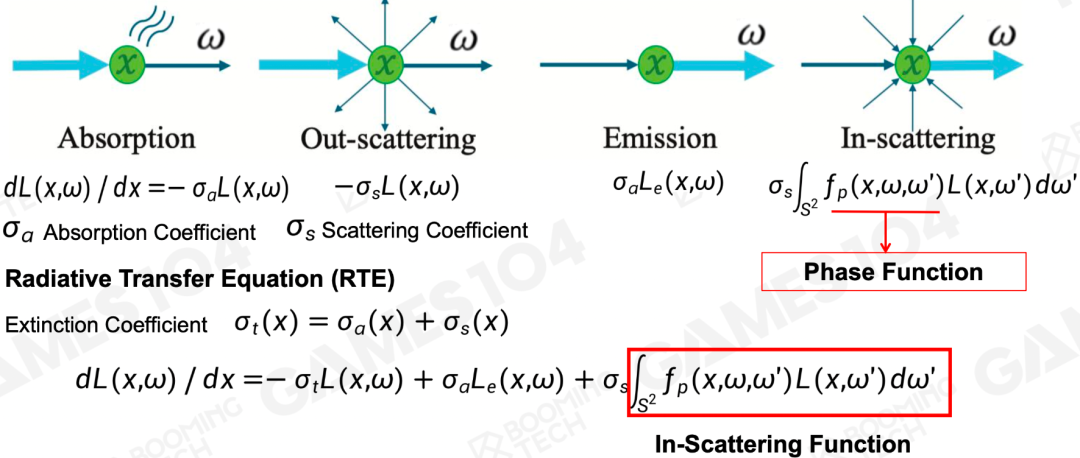

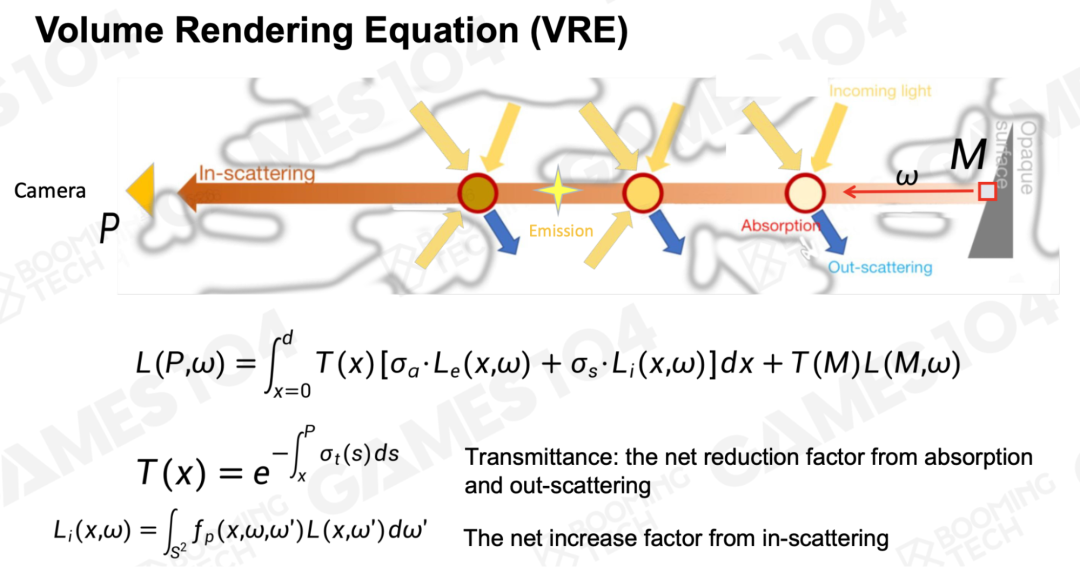

During post-processing and lighting computation, multiple factors must be considered: light intensity, angle, viewer perspective, scattering/refraction, and material absorption. In Unity’s Built-in pipeline, post-effects can be achieved via Post Processing Stack plugins or custom OnRenderImage() with Shader methods—offering high flexibility and extensibility. Lighting computation in game engines is complex; refer to the figure below for lighting analysis and equation representation—readers interested can experiment with parameter tuning. As the industry moves toward refinement, lighting has become a hallmark of high-end game presentation, with related rendering technologies also applicable to animation, film, VR, and more.

Source: Buming Technology

Additionally, game engine rendering systems belong to computer engineering science—fully leveraging engine capabilities requires deep understanding of GPU architecture, performance, power consumption, speed, and limitations. GPUs possess powerful parallel processing capabilities, enabling cost-effective generation of depth maps for occlusion culling, optimizing complex scene handling.

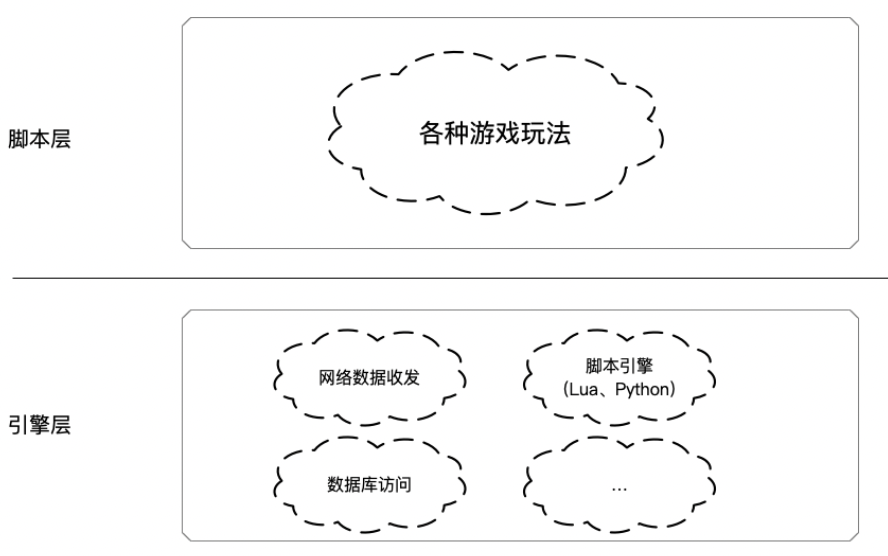

Industrialized Production & Creation: Backend Technology

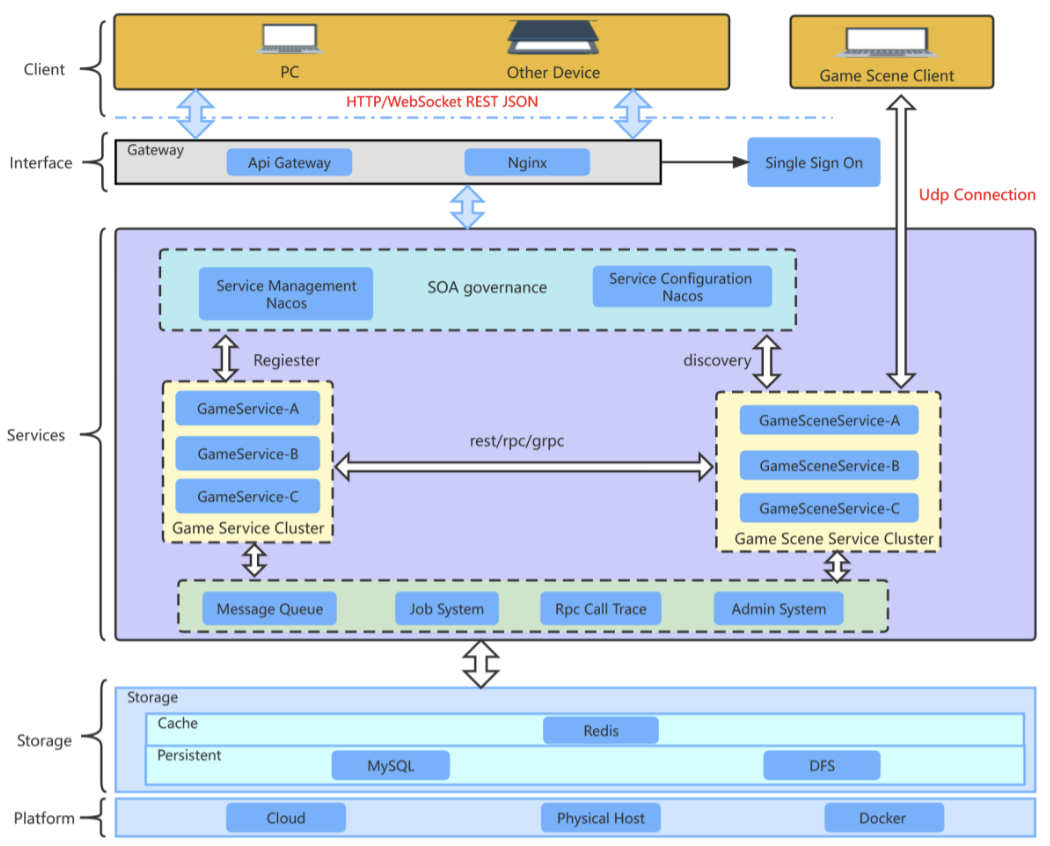

Backend development primarily covers server-side logic, data processing, network communication, and synchronization solutions. On the server logic side, backend developers handle server-side operations and game data storage—including player account management, game state synchronization, and multiplayer interaction support. They must design efficient database architectures to store game progress, achievements, virtual items, etc. Additionally, backend systems process requests from game clients—such as player interactions, user data, character upgrades, and resource purchases. Refer to the diagram below for a typical Web3 game backend architecture. Due to limitations in transmission speed and settlement times, current cryptographic and communication technologies prevent full on-chain deployment of large-scale Web3 game backends.

Source: Public market information

Regarding network communication and synchronization in backend development, developers use various protocols—TCP/IP, HTTP, WebSocket—to establish stable client-server communication links. During this process, custom network protocols must support high-frequency data exchange and real-time game state updates. Effective networking strategies and synchronization mechanisms reduce latency, ensuring all players see consistent game states. Especially in online multiplayer games, real-time data transmission and synchronization are central to delivering good user experiences.

During backend R&D, overall scalability, stability, and performance must be improved. Performance-wise, the backend must deliver low-latency caching and fast computational feedback, striving for real-time communication over HTTP. For stability and reliability, servers must be isolated to prevent one server failure from affecting others. For high scalability, developers must expand computational capacity and functionality using interconnected sub-servers communicating via TCP, IPC, etc., enhancing peak-load handling. The diagram below shows a representative backend architecture, serving as reference for storage, service, and interaction design.

Source: Public market information

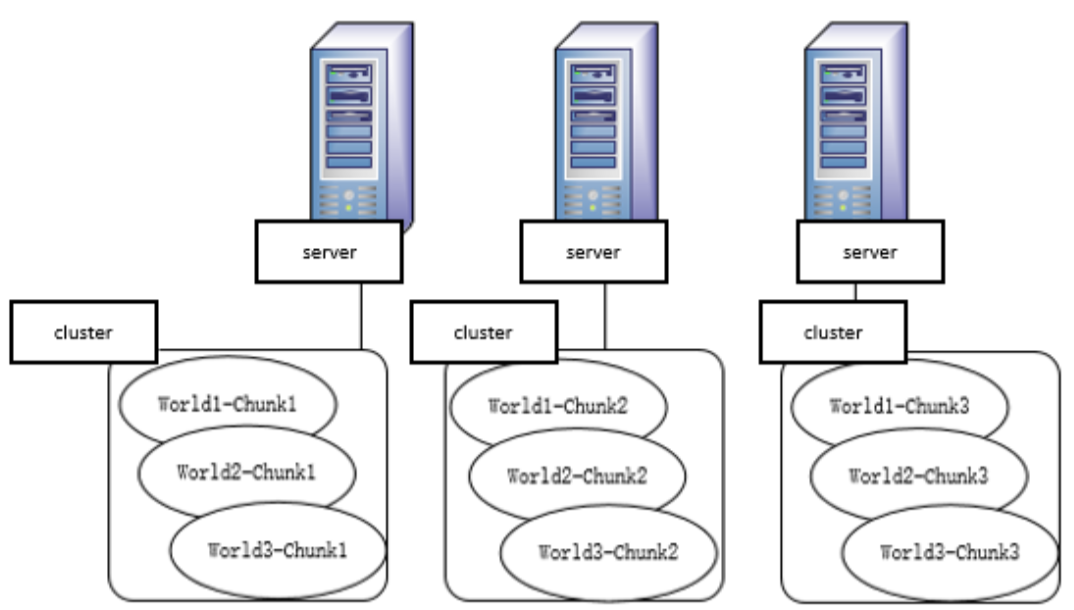

For multi-user, multi-scene Web3 games aiming to optimize user experience and reduce pressure from sudden traffic spikes, developers can deploy multiple servers. Within these, multiple world instances can cluster together to meet widespread user demand. Multi-server setups support real-time operations for many users, minimizing latency during heavy access and request volumes. See the diagram below for a reference setup.

Source: Public market information

Web3 game frontend and backend technologies are not entirely separate—they must cooperate extensively to provide holistic technical support. For anti-cheat measures, both frontend and backend can leverage their strengths collaboratively. Throughout integrated technical support, the frontend exploits advantages of tools like Unity, while the backend leverages data request and write capabilities. Key collaborative areas include:

-

Anti-Speed Hacks: Server-side verification with client cooperation;

-

Memory Data Encryption: Use Unity AssetStore plugins to encrypt client memory and reduce reliance on client-side data;

-

Protocol CD: Prevent frequent access to specific protocols by limiting frequency (e.g., one access every 300–1000 ms);

-

Protocol Encryption: Add extra bytes to protocol headers;

-

Prevent WPE Replay Attacks: Block repeated claiming or entry;

-

Monitor Non-Payment Channels: Track currency and asset acquisition via unofficial channels;

-

Anti-Movement/Action Speed Hacks: Detection logic can reside in player or scene processes;

The above uses cheat prevention to illustrate frontend-backend collaboration. By deeply understanding frontend and backend roles in game development, one sees distinct yet tightly connected responsibilities forming a complete game system. A compelling game experience stems from rich frontend interaction backed by powerful backend infrastructure. The above offers only a brief overview of Web3 game technology. Readers seeking deeper knowledge may refer to the following books:

-

Mathematics for Web3 Game Programming: Foundations of Game Engine Development, Vol 1: Mathematics; Mathematical Methods in 3D Games and Computer Graphics; 3D Math Primer for Graphics and Game Development; Essential Mathematics for Games and Interactive Applications; Geometric Algebra for Computer Science; Detailed Algorithms of Geometric Tools in Computer Graphics; Visualizing Quaternions; Div, Grad, Curl and All That; Computational Geometry

-

Game Programming: Learning Unreal Engine Game Development; Blueprints Visual Scripting for Unreal Engine; Introduction to Game Design, Prototyping, and Development; Unity 5 in Action; Game Programming Algorithms and Techniques; Game Programming Patterns; Cross-Platform Game Programming; Android NDK Game Development Cookbook; Building an FPS Game with Unity; Unity Virtual Reality Projects; Augmented Reality; Practical Augmented Reality; Game Programming Golden Rules; Best Game Programming Gems; Advanced Game Programming

-

Game Engines: Game Engine Architecture; 3D Game Engine Architecture; 3D Game Engine Design; Advanced Game Scripting; Programming Language Implementation Patterns; Garbage Collection Handbook: The Art of Automatic Memory Management; Video Game Optimization; Unity 5 Game Optimization; Hacker’s Delight; Modern X86 Assembly Language Programming; GPU Programming for Games and Science; Vector Game Math Processors; Game Development Tools; Designing the User Experience of Game Development Tools

-

Computer Graphics & Rendering: Real-Time 3D Rendering with DirectX and HLSL; Computer Graphics; Principles of Computer Graphics: A C-Language Approach; Principles of Digital Image Synthesis; Digital Image Processing; Mastering 3D Game Programming; Real-Time Shadows; Real-Time Computer Graphics; Real-Time Volume Graphics; Ray Tracing Algorithms and Techniques; Physically Based Rendering; Graphics Programming Methods; Practical Rendering and Computation with Direct3D; ShaderX Series; OpenGL Shading Language; OpenGL Insights; Advanced Global Illumination; Production Volume Rendering; Texturing and Modeling; Polygon Mesh Processing; Level of Detail for 3D Graphics; 3D Engine Design for Virtual Globes; Non-Photorealistic Rendering; Isosurfaces; The Magic of Computer Graphics

-

Game Audio: Game Audio Programming

-

Game Physics & Animation: Nature of Code: Simulating Natural Systems with Code; Computer Animation; Game Physics; Physics Modeling for Game Programmers; Physics-Based Animation; Real-Time Cameras; Game Inverse Kinematics; Fluid Engine Development; Game Physics Pearls; The Art of Fluid Animation; Fluid Simulation for Computer Graphics; Collision Detection in Interactive 3D Environments; Real-Time Collision Detection; Game Physics Engine Development

-

Game AI: Artificial Intelligence for Games; Artificial Intelligence in Game Development; AI Game Programming Wisdom; Unity AI Game Development; Behavioral Mathematics for Game AI

-

Multiplayer Game Programming: Multiplayer Game Programming; Massively Multiplayer Game Development; POSIX Multithreaded Programming; Developing Large-Scale Online Games; TCP/IP Illustrated Volumes 1–3

Industrialized Production & Creation: Art

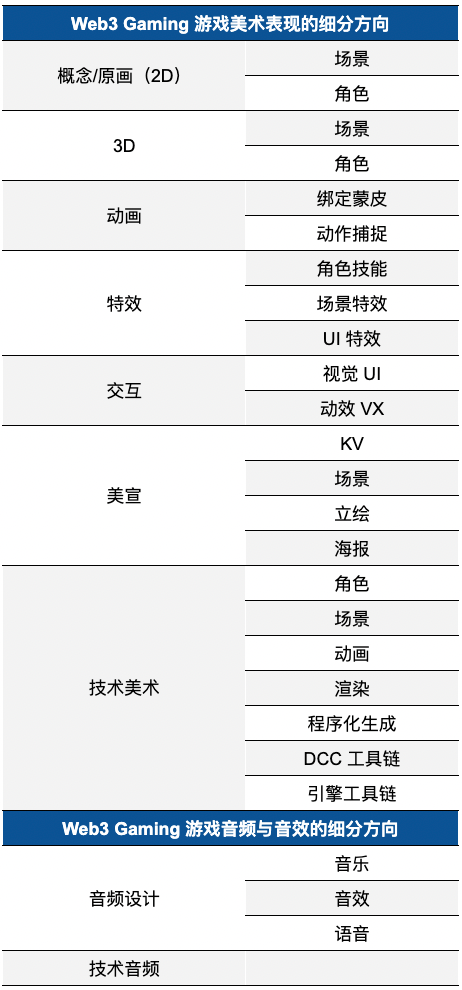

Due to space constraints, this section provides a brief analysis of art in Web3 games. Art plays a crucial role in Web3 gaming. Outstanding game works are not merely entertainment—they are artistic expressions, especially at the 3A level, where each high-level title becomes a cultural artifact. Studios enhance artistic presentation through multiple aspects such as effects, interaction, animation, and rendering. The table below outlines key considerations for Web3 game art across various subcategories. Given differences in game genre, development duration, and target audience, Web3 studios must carefully balance and prioritize artistic expression.

Source: YouSha Game Circle; compiled by Jake

Overall, a game’s art style must align with the theme and background established by designers. However, art evaluation remains subjective. The following eight criteria can guide assessment of a game’s artistic quality:

-

Art Style: Consistent with setting and theme, unique artistic expression, and appropriate historical or technological context;

-

Color Usage: Harmonious color schemes, symbolic meanings, and effective contrasts;

-

Environment Design: Scene details and atmosphere, interactive environmental objects;

-

Character Design: Character appearance, animation quality, movement, and integration with environment;

-

UI/UX Design: Interface layout, consistency with art style, clarity of information presentation;

-

Animation & Effects: Smoothness and expressiveness, visual impact of effects, integration of audio and visual feedback;

-

Technical Implementation: Realistic physical representation, balance between visual quality and performance;

-

Artistic Expression & Gameplay: Artistic support for core gameplay mechanics and narrative backdrop;

Furthermore, Web3 game skins are among the most popular purchasable components. From a consumer product standpoint, skins, accessories, and visual effects are key drivers of user spending. Distinctive artistic styles evoke varied psychological responses. Players' motivations for purchasing additional art content can be analyzed from the following perspectives:

-

In-Game Utility: NFT assets in Web3 games may provide gameplay bonuses such as increased attack, defense, speed, or income;

-

In-Game Economy: In some Web3 games, skins hold trading value—users and speculators buy and trade skins, potentially profiting from price fluctuations;

-

Social Factors: In multiplayer games, owning popular or rare skins attracts attention or admiration, enhancing players’ sense of superiority and social status;

-

Personalization & Self-Expression: Skins allow customized character appearances—choosing unique skins lets players express individuality, style, and preferences;

-

Display of Achievement or Status: Rare or limited-edition skins are often obtainable only through completing specific tasks, events, or purchases—owning them signals achievement or status within the game;

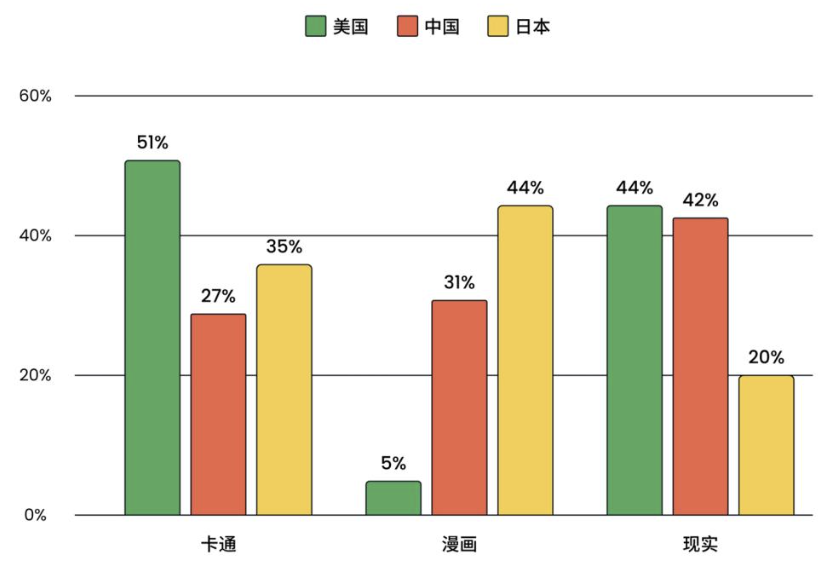

As of Q2 2024, regional preferences for art styles differ. In the U.S., cartoon, comic, and realistic styles are popular in a ratio of 51:5:44—the popularity of cartoons likely driven by American cartoon culture and casual game genres. In Japan, the ratio is 35:44:20, with "2D/anime-style" content favored by up to 80% of users.

Source: Public market information

Current emphasis on audio and sound effects varies among game studios due to multiple factors. Well-funded large studios can dedicate ample resources to high-quality audio design—hiring professional sound designers, composers, and engineers, using advanced tools to create immersive audio experiences that deepen atmosphere and emotional resonance. In contrast, smaller studios with limited budgets may lack sufficient audio resources. Financial and staffing constraints may force reliance on pre-made sound libraries or basic audio tools. Some opt for outsourced audio production. Consequently, audio quality may lag behind larger studios.

Audio also collaborates with other departments to elevate game quality. For example, in coordination with narrative teams, audio design involves VO work—audio teams consult repeatedly with writers to shape character performances, decide dialogue branching paths, and assist during voice recording to ensure proper pronunciation and faithful delivery of written lines. Collaboration with map editing, animation, and effects teams requires synchronized outputs—e.g., footsteps in grass as characters move, triggering key item effects in maps. Close interdepartmental coordination, frequent communication, and shared file access rights are essential to ensure high-quality, cohesive outputs.

Moreover, project scale and genre influence audio investment. For visually or story-driven games, audio may be secondary with lower investment. In contrast, games relying on sound to build atmosphere and immersion place significantly higher importance on audio design.

This is the second article in the Web3 Gaming Analysis Series, focusing on industrialized production and creation (technology and art). Stay tuned for the next installment: Testing and Operations.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News