HTX Venture: Exploring the BTCFI Rabbit Hole from the Perspective of Bitcoin Programmability

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

HTX Venture: Exploring the BTCFI Rabbit Hole from the Perspective of Bitcoin Programmability

As new applications like the Babylon staking protocol emerge and UTXO-native scaling solutions such as Fractal Bitcoin launch, the market potential of BTCFI is gradually being revealed.

Abstract

This article systematically explores Bitcoin's potential and challenges in the field of decentralized finance (BTCFI), starting from the feasibility and evolutionary path of Bitcoin programming. Bitcoin adopts the UTXO model and establishes a verification-centric contract system through its unique scripting language and opcodes. Compared to Ethereum smart contracts, Bitcoin contracts are characterized as "stateless" and "non-computable," which limits their functionality but also enhances security and decentralization.

With the implementation of the Taproot upgrade, Bitcoin's contract capabilities have been significantly enhanced. The introduction of Taproot—especially MAST and Schnorr signatures—enables support for more complex contract logic while greatly improving privacy and transaction efficiency. These technological innovations pave the way for further development of BTCFI, allowing Bitcoin to explore broader financial applications while preserving its core decentralized advantages.

Building on this foundation, the article analyzes how Bitcoin programming supports various BTCFI applications. By interpreting mechanisms such as multi-signature, time locks, hash locks, and exploring tools like DLC, PSBT, and MuSig2, it demonstrates the possibility of achieving trustless, decentralized clearing and complex financial contracts natively on the Bitcoin network. This native BTCFI ecosystem not only overcomes the centralization risks inherent in cross-chain bridging models like WBTC but also provides Bitcoin holders with a stronger foundation of trust.

The article concludes by emphasizing that the evolution of Bitcoin-based decentralized finance represents not just technological advancement, but a profound transformation of its ecosystem structure. With emerging applications like the Babylon staking protocol and native scaling solutions such as Fractal Bitcoin leveraging the UTXO model, the market potential of BTCFI is gradually being realized. As Bitcoin’s price rises, BTCFI will attract more mainstream users, forming a new financial ecosystem centered around Bitcoin. This shift will enable Bitcoin to evolve beyond the “digital gold” narrative into an indispensable decentralized financial infrastructure within the global economy.

Introduction

Since the launch of the Ordinals protocol in December 2022, the market has seen dozens of asset issuance protocols including BRC-20, Atomicals, Pipe, and Runes, along with hundreds of Bitcoin Layer 2 networks. Meanwhile, the community is actively discussing the feasibility of Bitcoin-native decentralized finance (BTCFI).

In the previous crypto cycle, WBTC emerged to attract Bitcoin holders into DeFi by locking Bitcoin through centralized custodians and minting WBTC tokens usable within Ethereum's DeFi ecosystem. WBTC targeted Bitcoin holders willing to accept the risks of centralized cross-chain bridges to participate in DeFi. As a representative bridge linking Bitcoin to EVM ecosystems, WBTC achieved one path toward BTCFI. This same model has been followed by EVM-compatible Bitcoin L2s and their DeFi projects in the current cycle. While WBTC reached over $9 billion in market cap on Ethereum, this accounts for less than 1% of Bitcoin’s total market cap, highlighting the limitations of this approach.

In contrast, if Bitcoin holders could directly use Bitcoin in BTCFI without cross-chain minting, while ensuring decentralized custody of funds, it would attract far more users and unlock a much larger market. This requires enabling Bitcoin programming under the UTXO structure. Just as mastering Solidity is essential for entering Ethereum DeFi, proficiency in Bitcoin programming is key to accessing the BTCFI market.

Unlike Ethereum contracts, Bitcoin contracts lack computational capability and function more like verification programs connected via digital signatures. Though initially limited in scope, Bitcoin programming’s potential has grown steadily due to continuous network upgrades and innovation from OG communities, with many research outcomes now translating into upcoming BTCFI products.

This article delves into the development path of BTCFI from the perspective of Bitcoin programmability, clarifying the historical and logical framework of Bitcoin programming to help readers understand real-world BTCFI implementations and their implications for Bitcoin holders and the broader ecosystem.

Foundations of Bitcoin Contracts

Satoshi’s Vision: UTXO, Scripting Language, and Opcodes

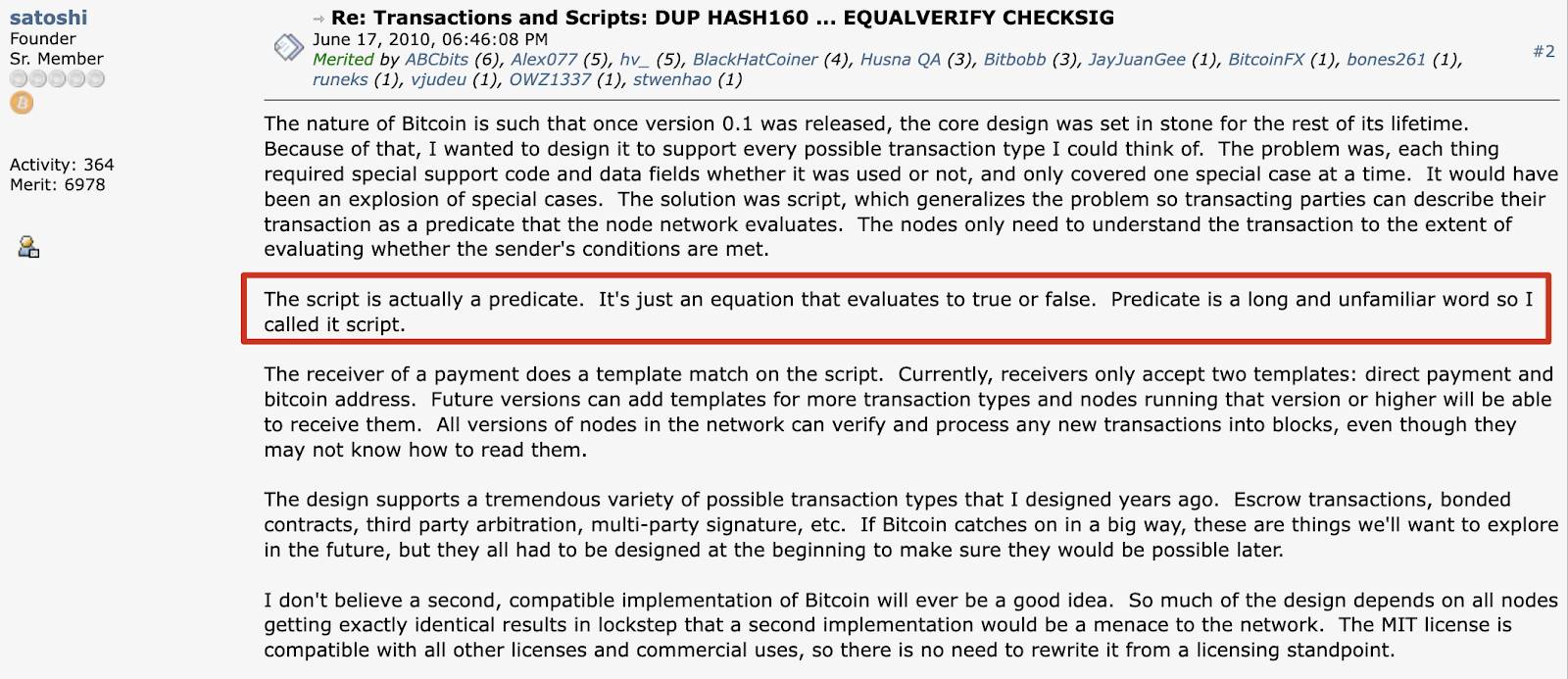

In 2010, Satoshi Nakamoto wrote on the Bitcoin Talk forum:

-

The core design of Bitcoin will be fixed after version 0.1 is released, so I want it to support as many types of transactions as possible. But each type needs special support code and data fields, covering only specific cases—and too many exceptions make things messy.

-

The solution is scripting. Transaction inputs and outputs can compile scripts into assertions verifiable by the node network. Nodes validate these assertions to determine whether sender conditions are met.

-

“Script” is just a “predicate.” It’s essentially an equation whose result is either true or false. But “predicate” is a long and rare word, so I called it “script.”

-

Receivers perform template matching on scripts. Currently, they accept only two templates: direct payments and Bitcoin addresses. Future versions can add more transaction templates; nodes running those versions will be able to receive them. All nodes in the network can verify and process any new transaction and include it in blocks—even if they don’t know how to read it.

-

This design supports various transaction types I designed years ago, including escrow transactions, bonded contracts, third-party arbitration, and multi-signature schemes. If Bitcoin becomes popular, these are areas we may want to explore later—but they must be built in from the start to ensure future compatibility.

Satoshi’s vision laid the groundwork for Bitcoin programming fourteen years ago. The Bitcoin network does not have “accounts,” only “outputs” (TXOs)—representing individual units of Bitcoin value and serving as the basic unit of state in the system.

Spending an output means using it as an input in a new transaction—effectively funding that transaction. This is why Bitcoin is said to operate on a “UTXO (Unspent Transaction Output)” model: Only unspent outputs are spendable during transactions. When spent, they enter a metaphorical furnace and emerge as new UTXOs, rendering the original TXO obsolete.

Each fund has its own locking script (also known as a scriptPubKey) and face value. According to Bitcoin consensus rules, the scriptPubKey forms a verification program—a combination of public keys and commands (opcodes)—which defines how the output can be unlocked. To unlock it, a specific set of data—the unlocking script, or scriptSig—must be provided. If the full script (unlocking + locking scripts plus opcodes) evaluates correctly, the output is considered “unlocked” and can be spent.

Thus, Bitcoin scripting enables programming of money itself—allowing specific amounts of Bitcoin to respond to particular input data. By designing scriptPubKeys, opcodes, and interaction flows between users, cryptographic guarantees can be established for critical state transitions in Bitcoin contracts, ensuring proper execution.

Here is a simple diagram of a standard P2PKH (Pay-to-Public-Key-Hash) Bitcoin script:

Suppose I want to pay Xiao Ming 1 BTC. I need to form a UTXO worth 100 million satoshis from spendable UTXOs in my wallet, then place Xiao Ming’s public key (along with signature-checking operators) into the UTXO’s locking script. Only Xiao Ming’s private key, signing appropriately, can unlock this fund.

In summary, Script is a very basic programming language composed of two types of objects: Data (e.g., public keys and signatures) and opcodes—simple functions that operate on data. A list of opcodes can be found here: Reference Link.

Bitcoin Programming Toolkit

As mentioned earlier, Satoshi originally intended Bitcoin to support transaction types such as escrow, bonded contracts, third-party arbitration, and multi-signature schemes. What tools exist to implement these, and how are they used in BTCFI?

Multi-Signature (MULTISIG)

- Its locking script format is M <PUB-1> <PUB-2> ... <PUB-N> N OP_CHECKMULTISIG, meaning it records N public keys and requires M valid signatures to unlock the UTXO.

- For example, a 2-of-3 multisig among Alice, Bob, and Chloe allows spending when any two sign. Its script code is: 2 <Alice> <Bob> <Chloe> 3 OP_CHECKMULTISIG. OP_CHECKMULTISIG is the opcode verifying that signatures match the provided public keys.

- Use cases include:

- Personal and enterprise fund management: A 2-of-3 multisig wallet ensures funds require at least two approvals, preventing single points of failure or malicious behavior from wallet manufacturers unless multiple collude.

- Transaction arbitration:

- Suppose Alice and Bob are trading, e.g., buying an ordinal NFT, but cannot exchange simultaneously. They agree to lock funds in a multisig output. When Bob receives the NFT, he releases payment. To prevent non-payment after delivery, a third party can be introduced, creating a 2-of-3 multisig. In case of dispute, the arbiter decides. If the arbiter confirms Alice delivered, she and the arbiter jointly release the funds.

- If the third party publicly shares their public key (e.g., an oracle), both parties can include it in the 2-of-3 multisig script, adding arbitration even without the oracle’s awareness. However, this gives the oracle control over contract outcomes, posing some risk. The Delicately Logarithmic Contract (DLC) discussed later improves upon this, enabling secure use in Bitcoin lending and other BTCFI applications.

Time Locks

Time locks control when a transaction becomes valid or when an output can be spent. This mechanism is crucial for re-staking, staking, collateralized lending, and other BTCFI scenarios. Developers must choose between relative time locks (nSequence) and absolute time locks (nLocktime):

- Absolute time lock (nLocktime): The transaction is only valid and includable in a block after a specified time or block height. At the script level, this is implemented via the OP_CLTV opcode, e.g., “this fund can only be spent after block 400,000.”

- Relative time lock (nSequence): The transaction is valid only after a certain number of confirmations since the creation of the prior transaction (the parent). At the script level, this uses OP_CSV, e.g., “this fund can only be spent three blocks after confirmation.”

Hash Locks (Preimage Verification)

Additionally, hash time-locked contracts (HTLCs), combining hash locks with time constraints, are commonly used in Bitcoin staking and re-staking:

- A hash lock’s locking script takes the form OP_HASH160 <hash> OP_EQUAL, requiring the unlocking script to provide the preimage of the specified hash.

- Hash Time-Locked Contract (HTLC): If the recipient fails to provide the preimage within a deadline, the sender can reclaim the funds.

Flow Control (Multiple Unlock Conditions)

The OP_IF opcode allows multiple unlock paths within a locking script. If any condition is satisfied, the UTXO can be unlocked. The HTLC described above uses such flow-control opcodes.

After the Taproot upgrade, MAST (Merkleized Abstract Syntax Trees) enables placing different unlock paths in separate Merkle tree leaves. Babylon’s BTC staking transactions utilize MAST, enhancing efficiency and privacy, as detailed later.

SIGHASH Tagged Signature Data

Bitcoin transaction signatures allow SIGHASH flags, specifying which parts of the transaction are covered by the signature. This enables partial modifications without invalidating the signature, expressing the signer’s intent or delegation. For example:

- SIGHASH_SINGLE | ANYONECANPAY signs one input and one output (with matching index), allowing all others to change freely. Andy can sign a 1 BTC input and a 100 Runes token output, enabling anyone willing to trade 100 Runes for 1 BTC to complete and broadcast the transaction.

Other examples include Schnorr signatures post-Taproot, applicable to Delicately Logarithmic Contracts (DLCs).

Limitations of Bitcoin Programmability

Bitcoin programming fundamentally involves a locking script defining verification conditions, an unlocking script providing data, and opcodes executing validation (signature checks, hash preimage checks, etc.). Once validated, funds can be spent. Key limitations include:

- Limited available verification methods: Implementing zero-knowledge proofs or other advanced validations would require a fork. Thus, Unisat’s proposed BTCFI extension, Fractal, maintains 100% compatibility with BTC but introduces controversial opcodes like OP_CAT and native ZK verification, resulting in partial separation from Bitcoin’s mainnet in terms of liquidity and security.

- No computational capability in Bitcoin scripts: Once unlocked, all funds become fully spendable without restrictions on usage. This makes implementing floating interest rates difficult in BTCFI lending, limiting designs to fixed rates. To address this, the community discusses “covenants”—restrictions on future spending of funds—which could unlock more BTCFI use cases. Proposals like Taproot Wizard’s BIP-420, OP_CAT, OP_CTV, APO, and OP_VAULT relate to this concept.

- UTXO unlock conditions are fully independent: One UTXO cannot decide its own spendability based on another UTXO’s existence or state. This limitation frequently arises in BTCFI lending and staking. Partially Signed Bitcoin Transactions (PSBT), discussed later, help solve this issue.

Evolution of Bitcoin Contracts

Compared to computation-based Ethereum contracts, Bitcoin contracts are verification-based. This stateless nature presents challenges for BTCFI product development. Over Bitcoin’s decade-long evolution, cryptographic techniques and signature innovations have dramatically improved privacy, efficiency, and decentralization, making BTCFI productization feasible.

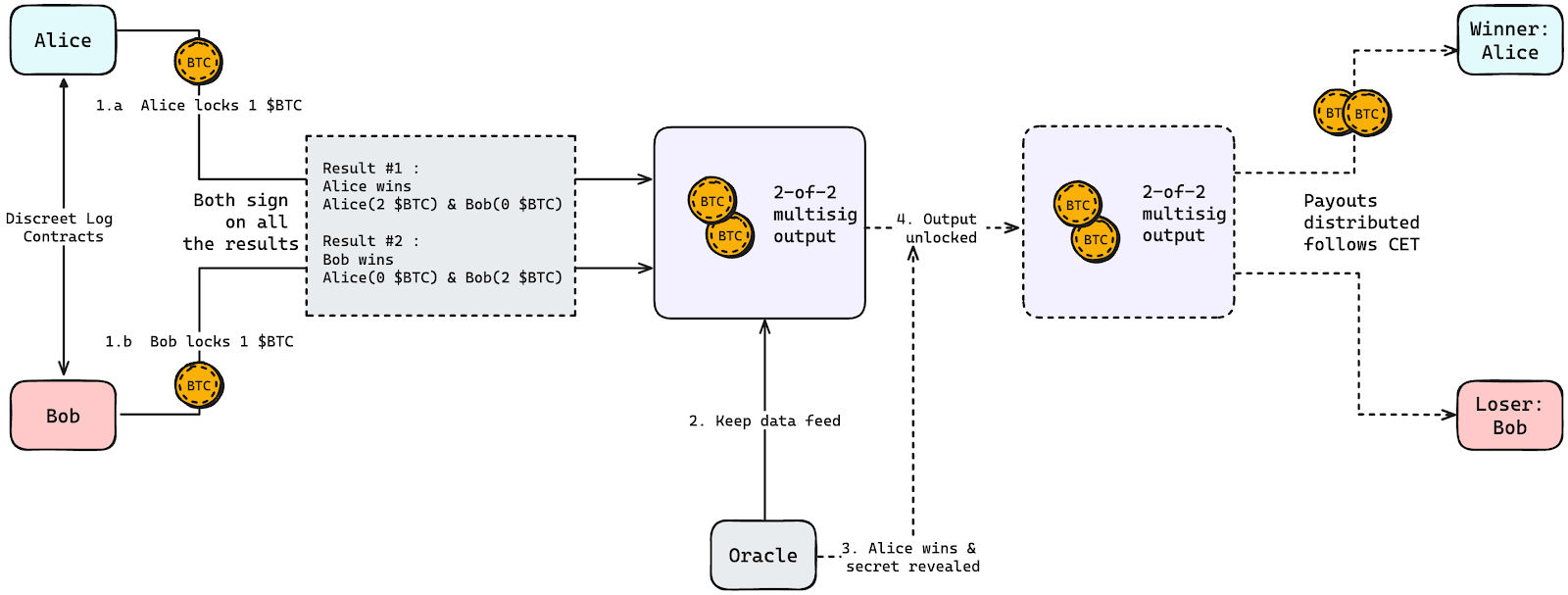

Discreet Log Contracts (DLC): Solving Decentralized Clearing in BTCFI

When lending, options, or futures protocols need to liquidate user positions based on oracle prices, they inevitably retain operational control over user assets, introducing trust costs where users must rely on protocol honesty.

Discreet Log Contracts (DLCs) were introduced to solve this problem. Using a cryptographic technique called adaptor signatures, DLCs enable Bitcoin scripts to encode financial contracts dependent on external events, while preserving full privacy.

Proposed in 2017 by Tadge Dryja (Research Scientist) and Gert-Jaap Glasbergen (Software Developer) from MIT’s Digital Currency Initiative, it was publicly demonstrated on March 19, 2018.

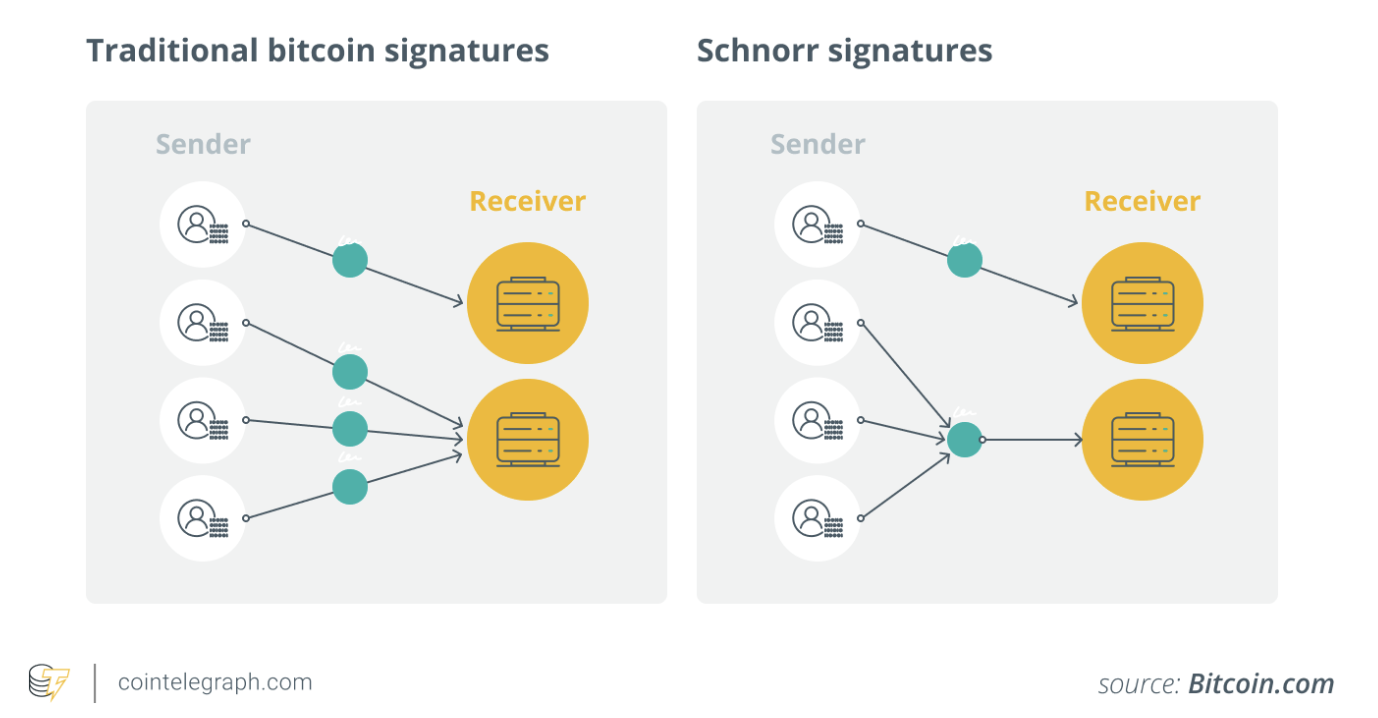

An adaptor signature becomes a valid signature only after a secret value is added. Schnorr signatures introduced in Taproot are an example of adaptor signatures.

Informally, a Schnorr signature has the form (R, s). Given (R, s'), knowing x (the secret), one computes s = s' + x to get a valid (R, s).

Here’s a simplified example:

- Alice and Bob bet on opposite outcomes of a sports match (no draws), each wagering 1 BTC. The winner takes 2 BTC. They lock funds in a multisig wallet requiring joint signatures to release.

- They select an oracle that will publish the match result (typically sourced off-chain, e.g., exchanges or sports sites).

- The oracle doesn’t need to know about the bet or participants. Its sole role is publishing results. Upon event resolution, it issues a cryptographic commitment proving the outcome.

- To claim funds, the winner (e.g., Alice) uses the oracle’s secret to generate a valid signature and spends the funds.

- The transaction settles on-chain. Since the final signature appears normal, there’s no on-chain indication this was a DLC—unlike typical multisig setups where contract details are public and oracles influence decisions.

Clearing Mechanism in Lending Protocols

Suppose Alice uses $ORDI as collateral to borrow 0.15 BTC. Her position enters liquidation status only when the oracle price of $ORDI drops below 225,000 sats/ordi. DLCs allow liquidators to permissionlessly clear her position once it's undercollateralized, while guaranteeing they cannot access her collateral if the threshold isn’t breached. In this scenario, Alice effectively makes a bet with the protocol on $ORDI’s price:

- If price falls below 225,000 sats/ordi, the protocol claims Alice’s entire collateral and assumes the BTC debt.

- If price remains ≥225,000 sats/ordi, nothing happens; ownership stays unchanged.

We require the oracle to commit to publishing a signature s_c_1 with nonce R_c when the price drops below 225,000 sats/ordi:

- Alice and the protocol create a commitment transaction using an adaptor signature (R, s') instead of a full (R, s), meaning neither party holds a directly spendable signature—they must reveal a secret (the oracle’s signature s_c_1.G preimage) to finalize it. Since the oracle’s nonce is predetermined, s_c_1.G can be constructed in advance.

- When the price drops below threshold, the oracle publishes (R_c, s_c_1). The protocol completes the counterparty’s adaptor signature, adds its own, broadcasts the transaction, and triggers settlement.

- Conversely, if the price stays above threshold, the oracle doesn’t publish s_c_1, so the commitment transaction cannot become valid.

At its core, DLC enables users and protocols to make agreements enforced on the Bitcoin blockchain, locking funds in a multisig address to form a DLC script. Funds can only be spent and redistributed according to predefined rules when the oracle publishes designated information at a specified time.

Thus, lending protocols leverage DLCs to implement trustless, permissionless clearing mechanisms involving external price oracles.

Lending protocols like Liquidium and Shell Finance use this technology for decentralized clearing.

Role of the Oracle

In DLCs, oracles provide regular price feeds and participate in generating and disclosing the secret value (secret) used in the mechanism.

Currently, there is no standardized DLC oracle product. Most lending protocols develop their own DLC modules, while standardized oracles like Chainlink handle off-chain data feeding. However, as DLC-based lending protocols go live and mature, several existing oracle projects are actively exploring dedicated DLC oracle development.

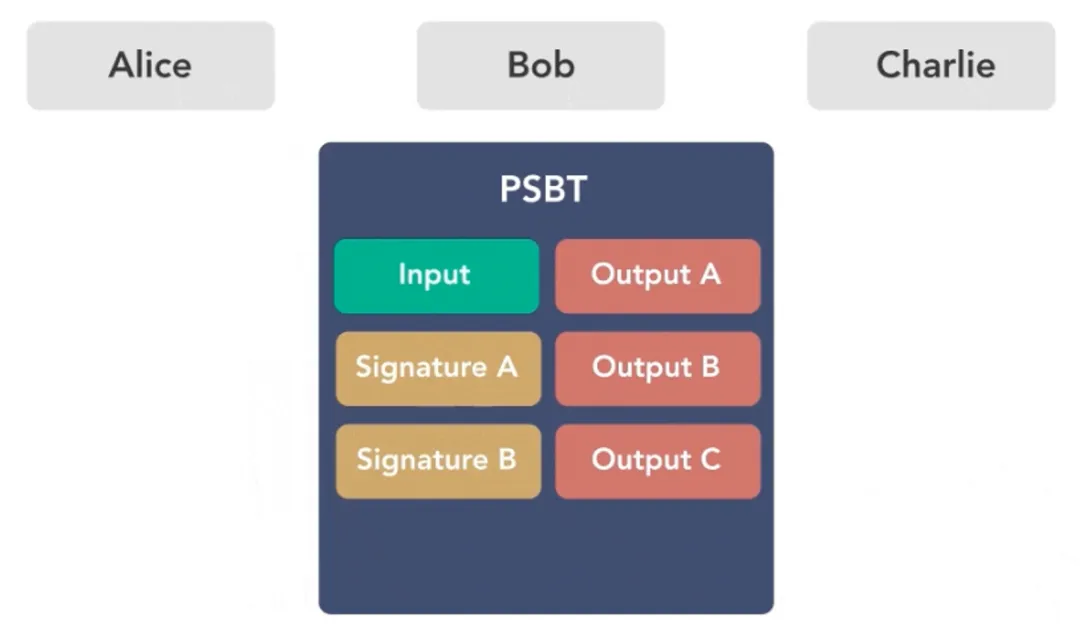

Partially Signed Bitcoin Transactions (PSBT): Enabling Trustless Multi-Party Transactions in BTCFI

PSBT originates from Bitcoin Improvement Proposal BIP-174, allowing multiple parties to concurrently sign the same transaction, merge their PSBTs, and produce a fully signed transaction. These parties may include protocol and user, buyer and seller, staker and staking service, etc. Any BTCFI application involving multi-party fund exchange can leverage PSBT. Most existing BTCFI projects use this technology.

Suppose Alice, Bob, and Charlie hold funds in a 2-of-3 multisig wallet and wish to split the amount equally. All three must sign the withdrawal transaction. Assuming mutual distrust, how can they securely proceed?

- Alice initiates the PSBT transaction, using the multisig UTXO as input and specifying three output addresses. Because PSBT ensures no other transaction can reuse any participant’s signature, Alice can safely sign and forward it to Bob.

- Bob reviews the PSBT, signs if acceptable, then sends it to Charlie for final signing and broadcasting. Charlie does the same.

“Partially signed” means each participant only verifies their relevant portion. If their part is correct, they can trust the final on-chain transaction will behave as expected.

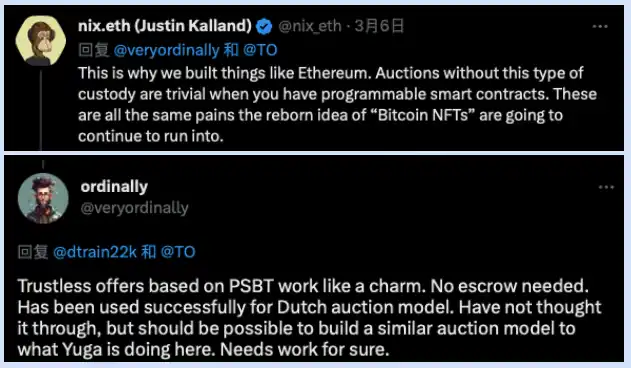

On March 7, 2023, Yuga Labs’ Ordinals NFT auction used a highly centralized custodial bidding model. All bids required depositing funds into Yuga’s address, severely compromising fund security.

Ethereum users pointed out this incident highlights the importance of Ethereum smart contracts. However, Ordinals developers responded that trustless PSBT-based quote transactions work well, enabling NFT buyers and Yuga Labs to transact without fund custody.

Consider a Bitcoin NFT trade where the seller’s public key is known. The buyer constructs a transaction with their UTXO input and an output receiving the NFT, signs it, converts it to PSBT, and sends it to the seller. The seller signs via the protocol, completing the trade.

This entire process is fully trustless. For the buyer, offer and receiving address are embedded upfront—any modification invalidates the signature. For the seller, the NFT only transfers upon their signature, at a verified price.

Taproot Upgrade: Opening Pandora’s Box for Bitcoin Ecosystem and BTCFI Explosion

Activated in November 2021, the Taproot upgrade aims to enhance Bitcoin’s privacy, improve transaction efficiency, and expand programmability. With Taproot, Bitcoin can host large-scale smart contracts involving tens of thousands of signers, hiding all participants while maintaining the size of a single-signature transaction, enabling more complex BTCFI operations. Nearly all BTCFI projects adopt Taproot’s scripting capabilities.

- BIP340 (BIP-Schnorr): Enables multiple parties to co-sign a single transaction and supports conditional execution as used in Discreet Log Contracts (DLCs). The amount of data committed to the chain matches that of a standard single-signature transaction.

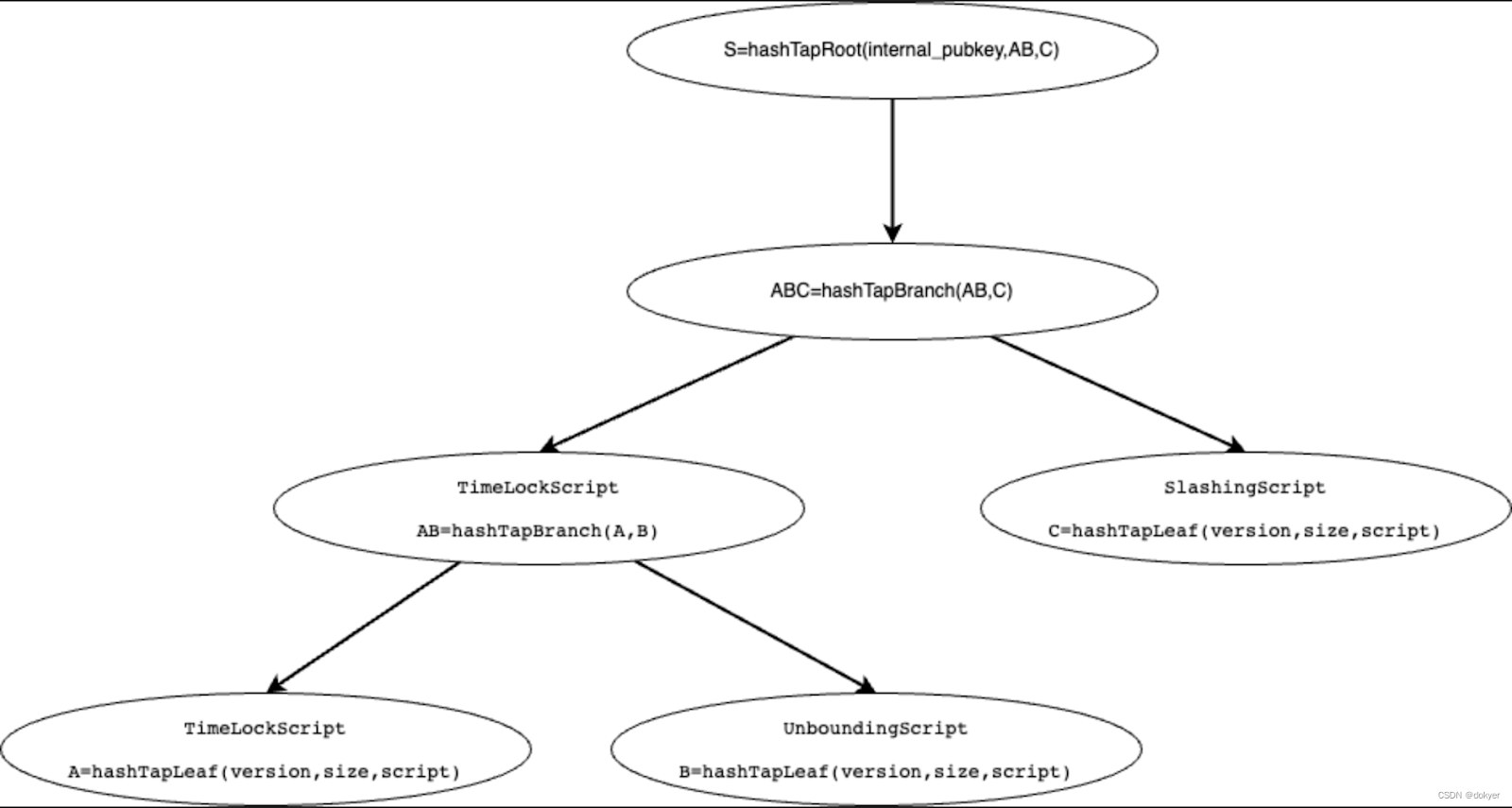

- BIP341 (BIP-Taproot): Introduces Merkle Abstract Syntax Trees (MAST), committing fewer contract data to the chain. This allows more complex contracts. Unlike current Pay-to-Script-Hash (P2SH) transactions, MAST lets users selectively reveal only necessary script parts, improving privacy and efficiency. Babylon uses MAST in BTC staking, combining multiple locking scripts into one transaction with three leaf scripts:

- TimeLockScript: Implements staking lock-up;

- UnboundingPathScript: Allows early unstaking;

- SlashingPathScript: Enforces penalties for malicious behavior.

These form leaf nodes, building up a binary tree as follows:

- BIP342 (BIP-Tapscript): Provides an upgraded transaction programming language leveraging Schnorr and Taproot. Tapscript also facilitates efficient future Bitcoin upgrades.

- Lays Foundation for Ordinals Protocol:

- Taproot introduced Taproot (P2TR) addresses starting with bc1p, allowing metadata to be written into the spent script path of a Taproot output, without appearing in the UTXO set.

- Since maintaining/modifying the UTXO set consumes significant resources, this approach saves space and increases per-block data capacity—enabling storage of images, videos, even games—accidentally making Ordinals possible. Common inscription addresses are Taproot (P2TR) addresses.

- Because Taproot script spending must originate from an existing Taproot output, inscriptions use a two-phase commit-and-reveal process. First, a commit transaction creates a Taproot output containing a script committed to the inscription content. Then, in a reveal transaction, the corresponding UTXO is spent, publicly revealing the inscription content.

- The emergence of new assets like Ordinals, BRC-20, ARC-20, and Runes has kept Taproot transfer adoption around 70%.

Ordinals and BRC-20: Creating Blue-Chip Assets for BTCFI and Unlocking Indexer-Based Programming

Ordinals fulfilled Bitcoin OGs’ dream of buying and selling directly on the Bitcoin mainnet, surpassing Ethereum NFTs in both hype and market cap.

- Introduced in January 2023 by Bitcoin core contributor Casey Rodarmor, Ordinals is based on ordinal theory, assigning unique identifiers and attributes to the smallest Bitcoin unit—the satoshi—turning them into unique non-fungible tokens (NFTs). By inscribing diverse data (images, text, video) onto sats, the Ordinals protocol enables creation and trading of Bitcoin NFTs.

- This expands Bitcoin’s utility and enables direct creation and trading of digital assets on the Bitcoin blockchain. Its enduring value stems from being built on Bitcoin sats, inherently tied to Bitcoin’s value and theoretically never dropping to zero.

BRC-20 is an on-chain record with off-chain processing, using JSON-based ordinal inscriptions to deploy token contracts, mint, and transfer tokens.

- It treats inscriptions as an on-chain ledger recording BRC-20 token deployments, mints, and transfers.

- Settlement requires off-chain queries, relying on third-party indexing tools to scan Bitcoin blocks and track all BRC-20 operations to compute final user balances. This may lead to discrepancies across platforms regarding account balances.

Beyond providing trading demand and blue-chip assets for BTCFI, Ordinals and BRC-20 inspire indexer-based programming approaches to enhance Bitcoin contract capabilities. Combinations of JSON “op” fields can evolve into inscription-based DeFi, SocialFi, and GameFi. Projects like AVM, Tap Protocol, BRC100, Unisat’s swap feature, and proposals for building smart contract platforms on Bitcoin Layer 1 all rely on indexer-based programming.

MuSig2: Decentralized Bitcoin Restaking and LST

Multisignature schemes allow a group of signers to produce a joint signature on a message. MuSig enables multiple signers to create an aggregated public key from their respective private keys and jointly produce a valid signature for that key. It is an application of Schnorr signatures. As previously noted, a Schnorr signature takes the form (R, s). Given (R, s'), knowing x (the secret), one computes s = s' + x to obtain (R, s). Here, private keys combined with random nonce values generate the aggregated public key and valid signature.

MuSig2 completes multisignature in just two rounds. The resulting aggregated public key is indistinguishable from a regular public key, enhancing privacy and significantly reducing transaction fees. Taproot is compatible with MuSig2, formalized in BIP-327: MuSig2 for BIP340-Compatible Signatures (published in 2022).

- Ethereum achieves liquid staking via smart contracts. Bitcoin lacks equivalent contract capabilities. Given Bitcoin whales’ aversion to centralized custodians, MuSig2 enables decentralized liquid staking on Bitcoin. Take Shell Finance’s approach:

- User and Shell Finance compute an aggregated public key and corresponding MuSig2 multisig address P using their private keys and two random nonces generated by wallets.

- Shell Finance constructs a PSBT transaction. User and Shell Finance assets are staked into Babylon from the MuSig2 multisig address P. Wallets provide additional nonce randomness and pass the aggregated public key.

- Upon completion of Babylon staking period, Shell Finance constructs a PSBT unlock transaction. User and Shell Finance jointly sign to release staked assets.

A third-party wallet, the user, and the LST project jointly generate the aggregated public key and signature. During this process, neither user nor project holds full signing power—both require the nonce to generate the key/signature. The wallet cannot move funds without the private key. If the project generates its own nonce, it poses a risk of malfeasance—users should remain cautious.

Technical documentation: Not publicly available

Current BTCFI Use Cases

Bitcoin programming isn’t complicated—it’s even simpler than languages like Rust. Its focus is creating verifiable, trustworthy commitments with superior technical security compared to Ethereum, setting boundaries for BTCFI development. The real challenge lies in identifying PMF (product-market fit) BTCFI products within these constraints. Much like early Ethereum developers didn’t immediately foresee x*y=k AMM algorithms but started with ICOs, order books, and peer-to-peer lending, BTCFI is now exploring viable applications.

Liquidity Booster: Babylon – The Catfish in BTCFI

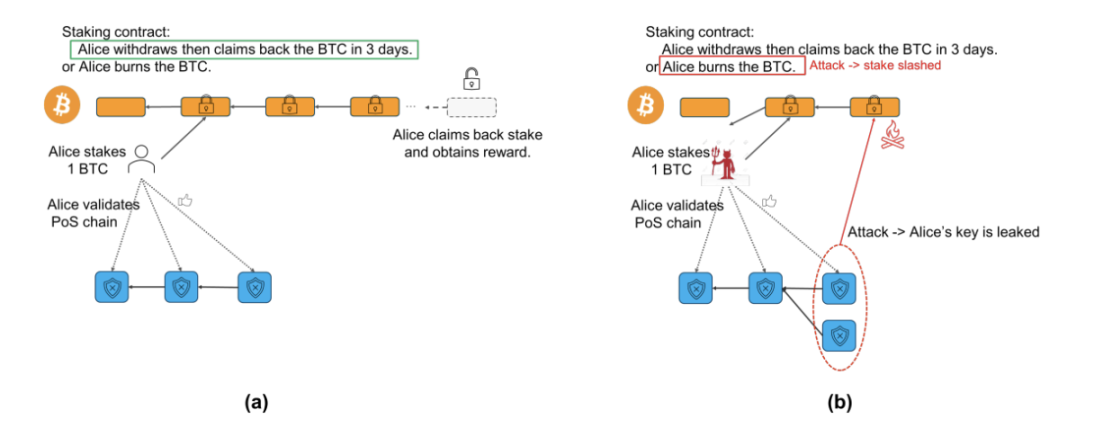

Babylon builds a fully trustless staking protocol, enabling direct yield generation from Layer 1 Bitcoin while extracting Bitcoin’s security and sharing it with PoS chains, acting as a universal shared security layer providing economic security for Cosmos and other Bitcoin L2s.

- Absolute Security: BTC staking offers a key advantage: if a protected PoS chain suffers an attack and collapses, the impact does not affect staked Bitcoin. For instance, if a PoS chain attack renders its token worthless, holders lose value—but in BTC staking, even if the protected chain fails, the user’s principal BTC remains intact.

- Slashing Mechanism: If a user engages in malicious acts (e.g., double-signing) on a PoS chain secured by Babylon, Extractable One-Time Signatures (EOTS) unlock the assets. Network actors then forcibly send a portion to a burn address.

Babylon’s mainnet is live, having completed its first phase with 1,000 BTC staked, and will soon launch Phase II.

Currently, Phase I stakers are primarily large holders, accounting for 5% of gas. More retail participants may join in Phases II and III.

First Major Influx of BTC into BTCFI Staking:

- Although Babylon doesn’t offer ETH-denominated staking rewards like Ethereum, a 3–5% APY is attractive enough for risk-averse large holders, miners, and Western and Asian funds bullish on Bitcoin’s ecosystem who avoid cross-chain wrapped solutions. With 100,000 BTC deposited, only $100M+ in equivalent token rewards would suffice.

- Babylon collaborates closely with Cosmos projects like Cosmos Hub, Osmosis, and Injective, encouraging them to become AVSs and offer their tokens as rewards for BTC restakers, further expanding Babylon’s deposit ceiling.

Babylon Injects Liquidity, Educates Users, and Energizes the BTCFI Ecosystem

- While Ethereum saw successful narratives around DeFi, L2s, and restaking, Babylon marks the first time Bitcoin mainnet users can stake for yield. Most Bitcoin holders avoid custodial or cross-chain risks. This gives them their first taste of BTCFI, potentially leading to further exploration of LSTs and other innovations.

- The Babylon ecosystem already hosts dozens of LST projects including StakeStone, Uniport, Chakra, Lorenzo, Bedrock, pSTAKE Finance, pumpbtc, Lombard, and Solvbtc, alongside various DeFi initiatives. Projects struggling to bootstrap TVL can leverage Babylon’s BTC staking to attract BTC via LSTs, then use those LSTs within their own ecosystems.

- Since Babylon’s rewards are denominated in tokens rather than BTC/ETH, it attracts fewer giants, avoiding centralization like Ethereum staking. Uncertain token profitability creates opportunities for early startups to capture market share.

Potential for Blue-Chip LST Assets on Bitcoin Mainnet, Driving BTCFI Demand

Babylon pioneers native BTC yield-generating staking, unlocking large-scale utility for trillions in dormant mainnet BTC. The resulting liquidity staking tokens (LSTs) can serve as natural blue-chip collateral in borrowing, stablecoins, and swaps—enabling BTCFI growth.

- BTCFI’s core challenge has been the lack of high-quality assets on Bitcoin mainnet, resulting in insufficient collateral for lending, low swap demand, and shallow liquidity pools. Currently, blue-chip assets on Bitcoin are limited to sats and ORDI in BRC-20, and NFTs like Node Monkey.

- But if a portion of Babylon’s staked BTC generates LSTs—similar to Lido’s stETH on Ethereum—that can be used as collateral in Aave, Compound, and achieve deep liquidity on Uniswap, BTCFI gains foundational traction.

- Imagine stakers wanting to borrow BTC against their LSTs, reinvest in staking, or hedge risks.

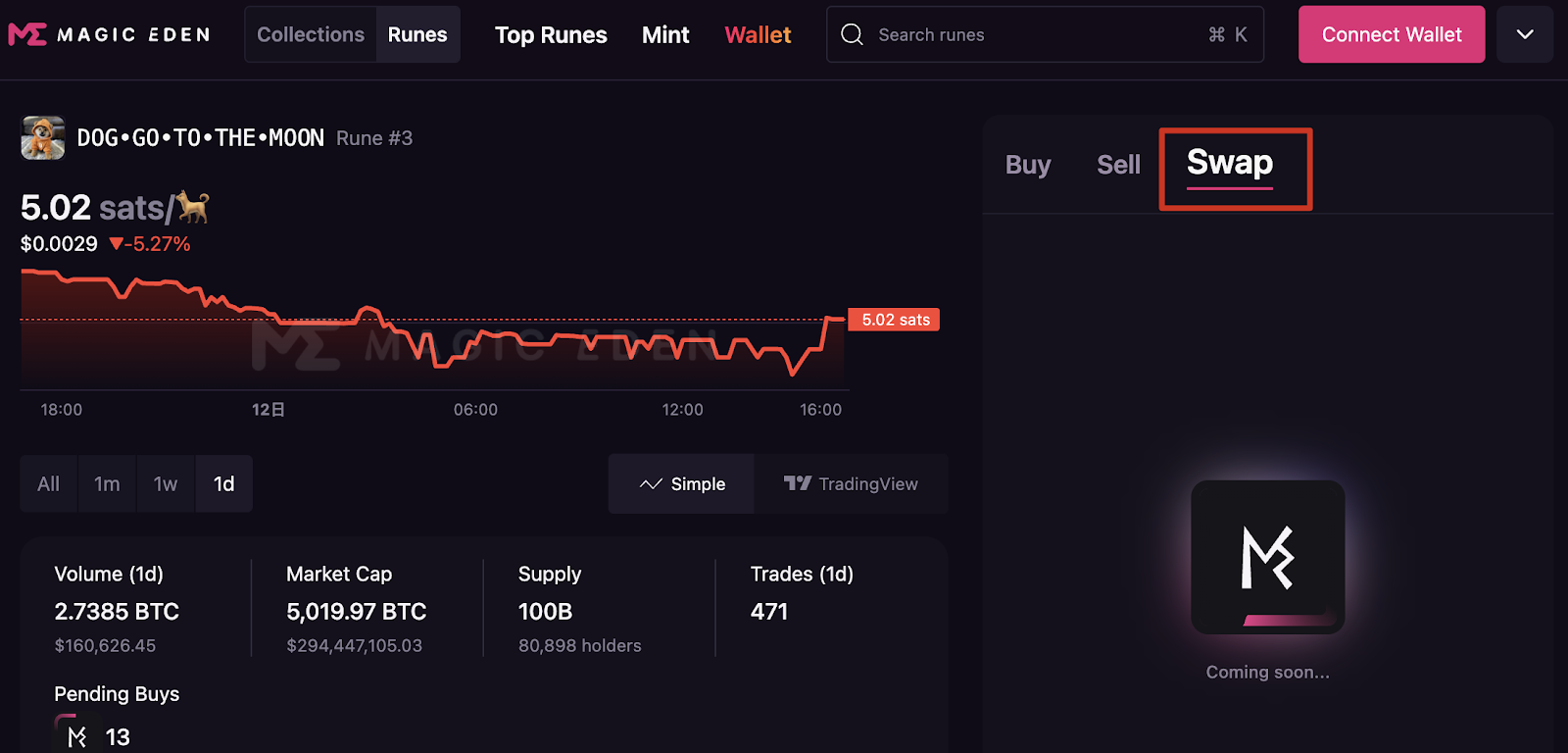

Innovation on Asset Issuance: Unisat and Magic Eden Launching DEXs

- Unisat’s BRC20 swap launches in September, supporting Runes mapped to BRC20. It will later support liquidity pools, enabling token issuance and trading without high gas mints or manual NFT-by-NFT transfers—enabling bulk trading.

- Magic Eden’s Runes DEX will launch in Q4 this year.

Native Pool-Based Lending and Stablecoin Protocols Coming Soon

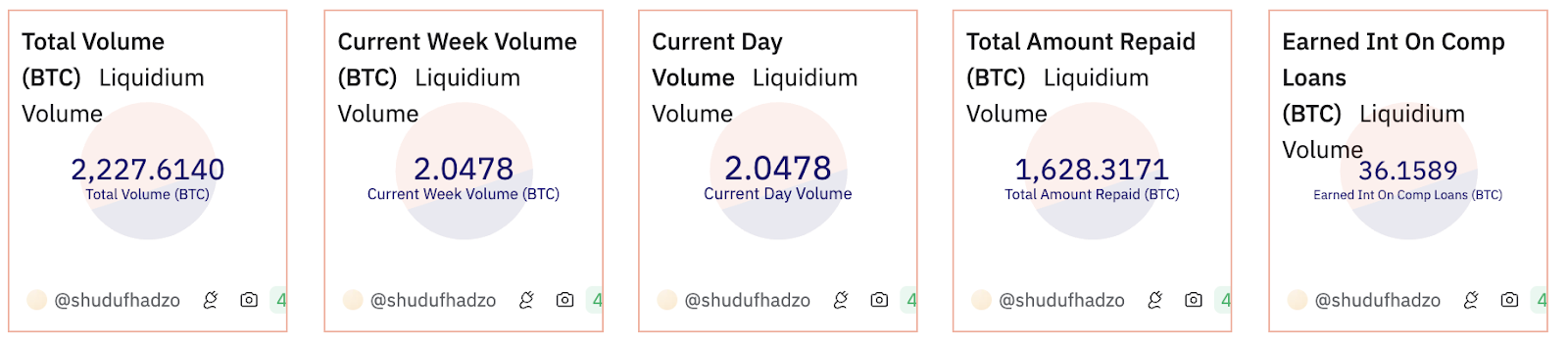

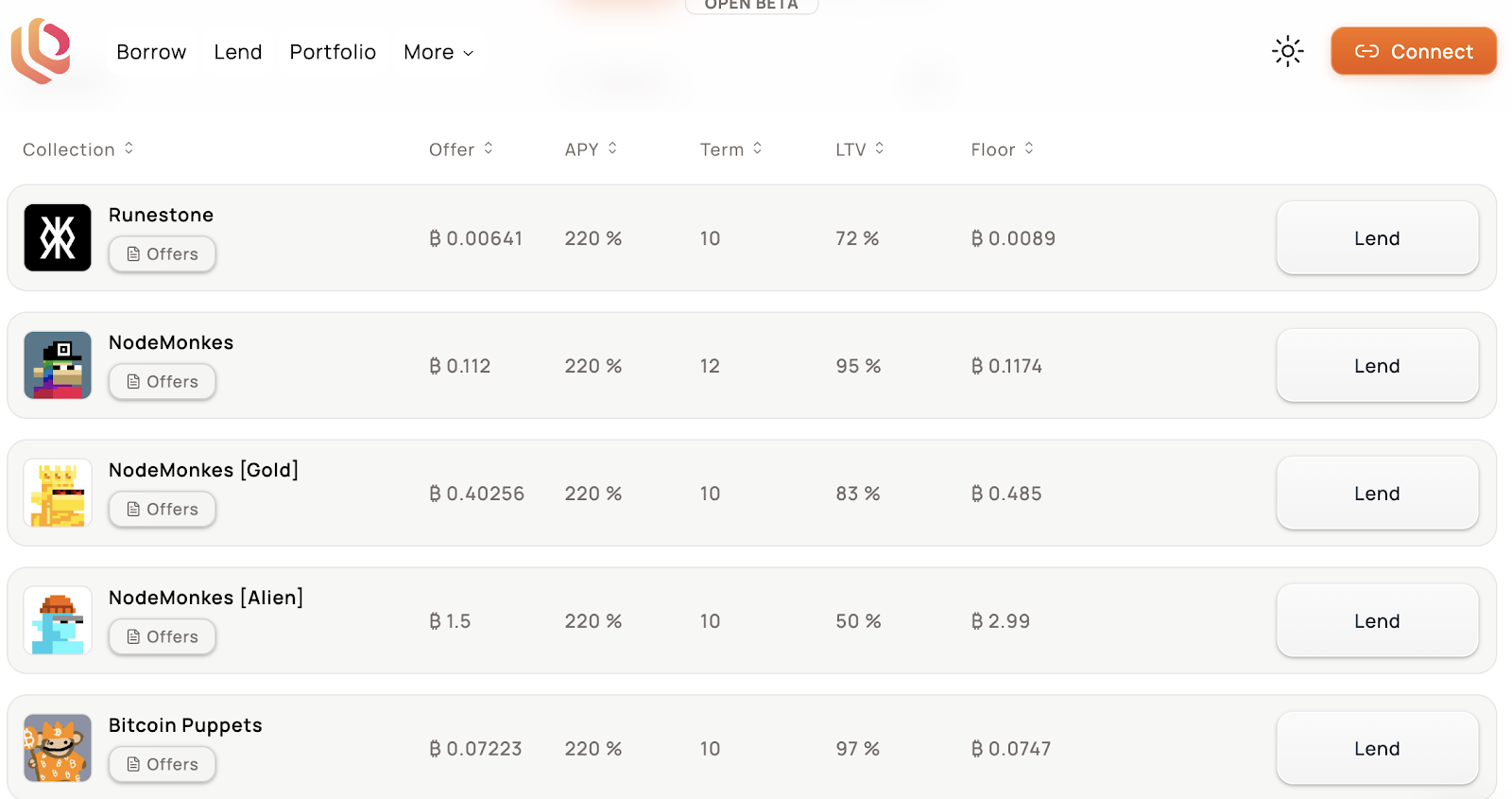

Liquidium is a lending protocol fully built on Bitcoin mainnet, using PSBT and DLC as described earlier:

- Lenders submit offers specifying metrics like LTV (loan-to-value ratio), interest rate, floor price, and deposit BTC.

- Borrowers select lenders from platform offers and deposit NFT or Runes assets.

Launched in October 2023, it achieved 2,227 BTC in volume within a year, demonstrating real demand for BTCFI lending using Bitcoin-native assets.

Key issues include:

- Low capital efficiency: If no borrower accepts an offer, the lender’s BTC sits idle. Each cancel-and-relist incurs fees. It lacks order matching, requiring discovery.

- Peer-to-peer liquidation: Only the lender and borrower can liquidate—third parties cannot participate.

- If NFTs or RUNEs drop below the loan value, borrowers may default. Lenders then receive the NFT or runes, effectively bearing downside risk.

- From the borrower’s view, if NFT/RUNES value drops, they must repay immediately or forfeit the asset, which is also unfair.

- To prevent defaults, loan terms are capped at ~10 days, resulting in very high APYs.

This might explain why Aave’s predecessor Ethlend struggled—peer-to-peer lending is hard to scale sustainably.

Shell Finance leverages the synthetic stablecoin $bitUSD to aggregate liquidity in lending and liquidation, achieving a positive flywheel effect and strong scalability.

Using DLC and PSBT for trustless, decentralized liquidation and transaction construction:

- Users can pledge assets like Ordinals NFTs, BRC-20, and Runes (and eventually Arch Network or RGB

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News