Web3 Social Myths: Failing to Understand the Difference Between Social and Community, and the Disastrous X-to-Earn Model

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Web3 Social Myths: Failing to Understand the Difference Between Social and Community, and the Disastrous X-to-Earn Model

This is Whistle's 16th article, discussing the Web3 Social sector and the limitations of monetization.

Author: Beichen

The Web3 industry has emerged from a prolonged bear market over the past year. While a true bull market is still far off, increasing voices suggest that a "Social Summer" may be on the horizon. This sentiment intensified recently when Telegram founder Pavel Durov was arrested at a French airport facing charges including fraud, money laundering, and terrorism—further spotlighting attention on social applications.

This isn't surprising. The crypto-native technical roadmap appears to have reached its endpoint (after all, most infrastructure already exists), yet mass adoption remains elusive. In theory, the social track offers the best chance to attract massive user bases and potentially evolve into self-sustaining ecosystems. As such, it now bears the weight of Web3’s stagnation anxiety. Whenever apps like friend.tech or Farcaster show signs of traction, the entire industry takes notice.

While I’m optimistic about the social track, I must sound a discordant note: the Web3 industry is filled with amateurish assumptions about social products, misunderstandings as deep as those surrounding NFTs, RWA, and DePIN.

We need to deeply understand social dynamics before discussing how they integrate with Web3 to form Web3 Social (or DeSo).

1. Social vs. Community

Whether discussing Web3 Social, DeSo, or SocialFi, these concepts ultimately aim to serve real users—and we must distinguish whether the services target social interaction or community building. Most people conflate them, especially in Chinese contexts where the terms are often used interchangeably. But in reality, social and community represent fundamentally different layers.

1.1 Social: Starting from Communication

Broadly speaking, social products originate from social interaction—which itself begins with communication.

Social interactions are micro-level exchanges, occurring between two individuals or within groups. The mechanism enabling these interactions is communication. Therefore, all social products must begin as communication tools.

Email was the earliest communication tool, first implemented by MIT in 1965. In 1973, the University of Illinois developed Talkomatic on the PLATO system—the first online chat platform, where users could even see each other typing in real time. Since then, communication tools have continuously evolved. Today, we use messaging apps like WhatsApp, WeChat, and Telegram, along with various email clients—core communication functions that were already established decades ago.

Why do users keep switching communication platforms? Each viral communication app succeeds because it offers a compelling, non-negotiable reason: either it's free, helps you find the right people, or resists censorship.

Tencent exemplifies success driven by freemium logic. In 1999, before China’s telecom operators launched SMS, OICQ (later QQ) allowed free messaging bypassing phone networks. However, since messages were sent via PC, this left room for operators to later charge ¥0.1 per SMS starting in 2000—setting the stage for WeChat’s rise during the smartphone era.

But why did WeChat succeed over the more mature QQ? First, mobile QQ merely ported its desktop version to mobile, resulting in poor UX compared to WeChat, which was designed natively for smartphones. More importantly, WeChat introduced voice messages, voice calls, and video calls—fully replacing traditional SMS and calling features.

If we follow the trajectory of “free” innovation, the next breakthrough might come from free satellite calls and satellite internet access.

Success driven by “finding the right people” includes dating apps like Momo (for strangers), Blued (LGBTQ+), and Qingtengzhilian (high-education matchmaking). Censorship-resistant platforms include Telegram and Signal.

Clubhouse combined both strengths—access to influential people and freedom to discuss sensitive topics—making its otherwise ordinary voice-chat format extremely desirable upon launch.

In short, social interaction is a fundamental human behavior, enabled primarily through communication. No matter how complex a social product becomes, its core always stems from communication, later evolving by integrating additional services into community-oriented platforms.

1.2 Community: Social Media and Social Networks

A community (community) emerges when numerous individuals and groups engage in interconnected social behaviors forming an organic whole.

Note: A community is not just a simple aggregation (“create a group chat and let people idle talk”). It requires members to actively contribute information, resources, or support based on shared goals (interests, visions, etc.). When consumption exceeds production within a community, it decays—like cancer cells consuming host energy until collapse.

Thus, building community products is far harder than creating communication tools—it borders on religious movement-building. Solving one communication pain point (e.g., free voice chat) can spark temporary virality, but most social apps fail to retain users long-term. Retaining users is vastly harder than acquiring them.

Based on how communities retain users, we can categorize them into two types: content-centric (social media) and relationship-centric (social networking services, SNS)—terms that often blur the line between social and community.

Content-centric social media traces back to Notes, also created on the PLATO system in 1973 (same year as Talkomatic). Notes laid the foundation for BBS systems, leading to forums,贴吧 (tieba), blogs, and eventually evolving during the mobile internet wave into today’s Twitter, Weibo, Instagram, and Xiaohongshu. These platforms revolve around interests, continuously accumulating user-generated content (UGC).

Relationship-centric social networking services refer to communication tools built around connecting specific people. But a product only qualifies as a true social network when it functions as a contact list. Examples include WeChat (existing offline acquaintances), Momo (strangers), and LinkedIn (professional networking).

1.3 From Single Function to Integrated Platform

Even after clarifying the distinction between social and community, definitions remain messy—because modern social products rarely offer just one function. Instead, they integrate multiple layers and dimensions.

This integration is the root cause of widespread confusion about social products: focusing only on surface-level feature combinations without uncovering the underlying drivers and evolutionary paths.

Take WeChat again. It first leveraged free text and voice messaging to migrate users’ real-world relationships, establishing a vast network of close contacts. Then features like “People Nearby” and “Shake” unlocked stranger interactions, helping it surpass 100 million users rapidly.

Later, it strengthened communication capabilities with voice/video calls and expanded into content territory via “Moments,” “Official Accounts,” and “Channels.” Adding payments caught Alipay off guard.

This same analytical framework applies to X (formerly Twitter), Facebook, Telegram, and even TikTok. Yet almost every Web3 Social analysis report reads like it was written by someone who only started using WeChat two years ago—naively combining features without understanding their foundational purpose. Founders inspired by such analyses end up copying WeChat wholesale, replicating comprehensive functionality without considering how real users are acquired and retained.

This article could easily organize everything into neat tables—by communication method, content type, relationship model, and media format—then dress it up with buzzwords to analyze random combinations (e.g., “a crypto app for Web3 professionals supporting voice calls, live streaming, and trade signals”)—appearing professionally rigorous while offering zero practical guidance.

2. Web3 Social Landscape

After this extensive setup on social dynamics, we finally arrive at Web3! Designing Web3 Social is significantly more complex than conventional internet social products due to fundamental differences between internet and blockchain protocols.

2.1 Model Layers: Internet vs Blockchain

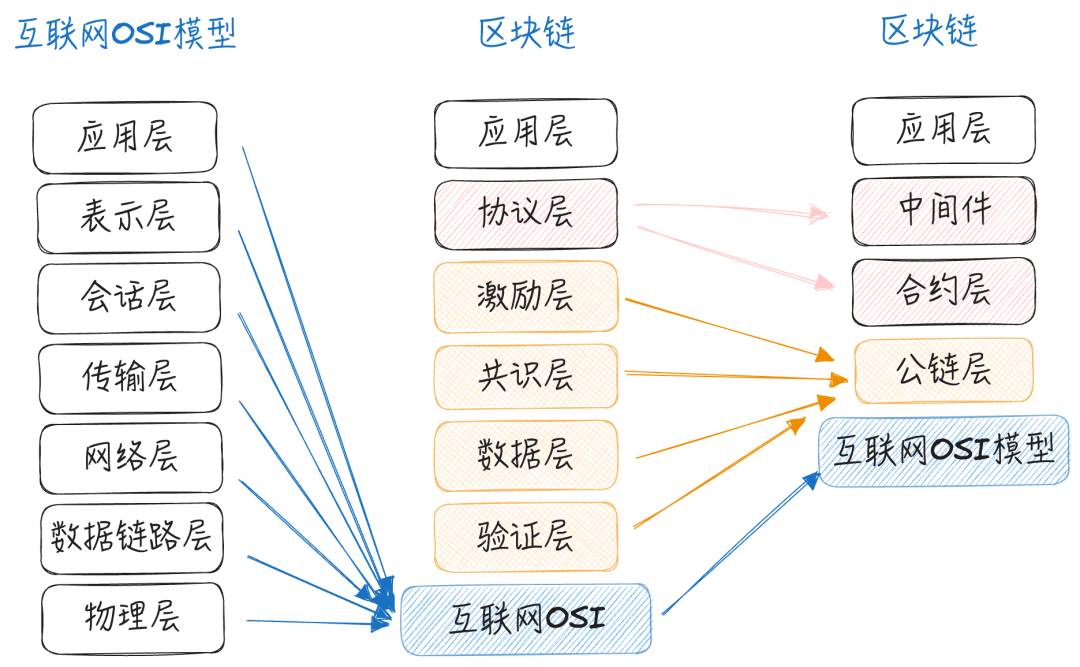

The internet follows the OSI 7-layer model, where developers typically focus only on the topmost application layer. Blockchain lacks standardization, making it inherently more complex. Below is a reference layered model used for subsequent analysis.

In the blockchain world, if blockchain networks are Layer 1, then the internet serves as Layer 0—the foundational communication infrastructure. Blockchain networks themselves can be subdivided into network, data, consensus, and incentive layers. However, mainstream public chains bundle these together, so we’ll treat them holistically.

Above public chains sits the protocol layer (Protocol), encapsulating scripts, algorithms, and smart contracts. Crucially, these are not end-user products but minimal-function components—some executed on-chain, others as off-chain middleware.

Since blockchain enables shared data layers, these smart contracts and middleware are open and infinitely composable. In theory, developers can combine and optimize them to build new applications.

The problem? The protocol layer remains severely underdeveloped (with rare innovations mostly confined to DeFi; the social sector lacks revolutionary tools). Thus, prospects for Mass Adoption applications built atop this foundation remain slim.

2.2 Two Logics: Bottom-Up vs Top-Down

Within the Web3 Social space, two competing product philosophies exist: crypto natives prefer bottom-up development of native encrypted social tools, while Web2 migrants favor top-down approaches—building mature Web2-style products first, then gradually adding Web3 elements.

2.2.1 Bottom-Up Approach

There are two variants of the bottom-up approach: identity infrastructure centered on accounts, and social graphs centered on content.

In Web2, the most important account is the email address. In Web3, it’s DID (Decentralized Identifier)—self-created and managed on-chain, enabling private interactions across apps.

The canonical example is ENS (Ethereum Name Service), a decentralized domain system built on Ethereum allowing individuals, organizations, or devices to manage digital identities (though the earliest on-chain domain system was Namecoin, forked from Bitcoin in 2011).

However, current DID projects face a critical issue: beyond serving as wallet domains, they lack genuine, widespread use cases.

The content-centric social graph involves putting users’ social data on-chain—profiles, posts, follows, etc. The prime example is Lens Protocol, which tokenizes and NFT-ifies user social data and behaviors, enabling developers to build new social apps on top. Yet no truly vibrant social app has emerged from it yet.

Simple tools like Blink also deserve attention—they convert on-chain actions into embeddable links across websites and social platforms.

2.2.2 Top-Down Approach

The top-down path is straightforward: take an existing social product and retrofit it with blockchain (“chain reform”). There are two subtypes.

One involves first building a solid Web2 social product, then incrementally adding Web3 modules. The earliest and most successful example was Bibox (Bihu), though it eventually shut down. Many similar projects followed, especially during the 2022 “X-to-Earn” boom in SocialFi, introducing mechanisms like “posting = mining,” “commenting = mining,” “chatting = mining.” Nearly all have since collapsed. The SocialFi model is fundamentally flawed—a point elaborated below.

Among attempts transitioning gradually from Web2 to Web3, Farcaster stands out as the only relatively successful case. It exercises restraint—avoiding SocialFi mechanics—and focuses on nurturing an authentic crypto community. Web3 features exist as plugins. Given that crypto communities naturally generate wealth effects, this fosters memecoins led by degens (note: if listing companies were as easy as launching tokens, Snowball would crush all tech giants).

The second variant is more subtle and easily mistaken for native Web3 products. These often feature decentralized databases combined with DID, DAO tools, etc., enabling anyone to build custom Web3 apps on top.

The deception lies in appearance: all modules seem authentically Web3, functionally comprehensive. But step back, and you realize they’re simply re-implementing mature Web2 social products entirely using Web3 technologies (e.g., cryptographic signatures, distributed systems), thus differing little in essence from their Web2 counterparts.

Examples include Ceramic and UXLink, which appear to span multiple layers of the blockchain stack—from infrastructure to UI—forming seemingly complete Web3 social ecosystems. It’s like reconstructing a wooden pavilion using steel and concrete: technically possible, but unnecessary—why not design something uniquely suited to the new materials?

2.2.3 Limitations of Both Approaches

In sum, whether building identity infrastructure around accounts, content-centric social graphs, or fully re-implementing Web2 social apps using Web3 tech—all these approaches feel more like tools for digital preppers than solutions for the general public. Most react with “respect, but don’t get it,” making mass-market success unlikely.

Perhaps we should set aside ideological purity and reconsider hybrid models like Farcaster (Web2.5). Their viability brings us back to the original argument: success in social and community building depends less on technology and more on deeper product intuition.

3. X-to-Earn and Its Applicable Scenarios

Yet imagination around Web2.5 products remains largely captured by the “Web3 version of XXX” trope—e.g., Web3 TikTok (Drakula), Web3 Instagram (Jam)—where the “Web3 part” manifests almost exclusively in monetization, i.e., Fi, or what we commonly call X-to-Earn.

3.1 Monetization Is Essentially a Points Mall

Monetization seems to be Web3’s only magic wand for reinventing internet products. Whether the 2017-era “tokenization” and “blockchain reform” trends or the 2021-born “X-to-Earn” craze, the core idea is incentivizing retention through profit-sharing.

Internet platforms have long used mature point systems: “complete tasks → earn points → redeem goods/rights in store” to boost engagement—but only as auxiliary operational tactics. After all, money doesn’t grow on trees. If value isn’t extracted from users (sheep), it must come from elsewhere (pigs); in normal business models, such subsidies inevitably hit cash flow limits.

Only Ponzi schemes break this constraint—launching point-based products directly funded by new entrants. Around 2015, many middle-aged women in China’s tier-3/4 cities promoted apps claiming to make money—but requiring upfront membership fees.

ICO offered a more elegant alternative: unlike offline Ponzis needing recruiters, ICOs issue tokens directly—no need for explicit successors. Existing holders, expecting price rises, may even buy more themselves. Plus, secondary markets avoid direct accountability issues.

Therefore, most Web3 monetization schemes are essentially repackaged internet point malls—except instead of redeeming for tangible goods, users chase secondary market valuations.

3.2 Challenges of Monetization Models

Naturally, we shouldn’t dismiss monetization entirely—it has valid use cases, just not in most social/community contexts.

The first challenge is managerial: current performance evaluation methods cannot accurately identify meaningful user behaviors, making targeted incentives impossible—and inevitably attracting bounty farmers.

Even if rules specify exact requirements (e.g., daily session duration, task completion), bot farms exploit them effortlessly, outcompeting real users. Almost every X-to-Earn project suffers this fate.

Even if a project accurately identifies valuable behaviors and designs fair incentives, there remains a psychological barrier: monetization shifts user motivation from intrinsic interest in the product to extrinsic rewards. When incentives fade, so does engagement.

Worse, for social products, positive interaction itself is the reward. SocialFi constantly redirects attention toward monetary gains, ultimately rendering the product experience hollow.

3.3 The Absurdity of SocialFi

Imagine a romantic relationship-tracking app under SocialFi logic: quantifying daily acts like chatting, giving flowers, kissing, hugging—and rewarding them. For couples using it, romance would quickly feel mechanical and joyless.

If this sounds absurd, that’s exactly what SocialFi projects do. Psychology explains this via the over-justification effect: attaching external rewards to intrinsically motivated behaviors undermines internal drive, shifting control to external incentives.

Monetizing user behavior only works in rigid payment scenarios—e.g., adult content, gambling, drugs, or fan economies—where users already have strong willingness to pay, generating sustainable cash flows. Only then can monetization enhance operations.

All current X-to-Earn projects, despite intricate designs, fail to generate lasting positive revenue—doomed to decay through endless circulation.

Conclusion

Web3 Social carries the Web3 industry’s hopes for Mass Adoption—but remains shrouded in conceptual fog.

Myth One: Widespread confusion between social and community leads analysts to fixate on superficial features, ignoring true drivers and evolution paths. Product design thus favors bloated, all-in-one solutions based on unfounded assumptions. In reality, users lack compelling reasons to adopt them.

Myth Two: Crypto purists believe encryption technology revolutionizes social apps, but it hasn’t changed communication fundamentals (e.g., text → voice → video). Innovations like DID and social graphs are minor tweaks rather than paradigm shifts. Such incremental improvements cater more to digital survivalists than mainstream users.

Myth Three: Web2 migrants assume superior product design plus tokenized incentives will attract loyal users. In reality, they only draw bounty hunters. Monetization diverts attention from social experience to financial gain. Since rewards are finite (lacking sustainable cash inflows), products eventually stagnate and die. Monetization should only supplement—not create—user willingness to pay.

Thus, neither Web3 technology nor business models can independently spawn mass-market social products. That said, Web3 social isn’t hopeless. After dispelling myths, only two viable paths remain.

Either follow Farcaster or Telegram: first cultivate a genuine crypto community, then support Web3 features as plugins. Crypto communities naturally generate wealth effects.

Or follow ENS or Lens Protocol: continue innovating at the protocol layer, developing novel middleware. Though currently niche, these may serve as future technical reserves—eventually integrated as plugins into major Web2 social platforms, enabling new interaction paradigms and unforeseen use cases (e.g., credit scoring based on ENS).

This article began by asking what Web3 Social can do—but the clearer insight became what it shouldn’t do. In the medium term, building crypto communities offers far greater certainty.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News