Bitcoin Staking: Technical Overview and Security Analysis

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Bitcoin Staking: Technical Overview and Security Analysis

In the future, Chakra will continue collaborating with Babylon to launch a series of staking events, providing users with multiple收益.

Recently, Babylon launched a Bitcoin staking event on Testnet-4, sparking community discussions around Bitcoin staking. Today, the Chakra Research team will guide you through the latest Bitcoin staking schemes.

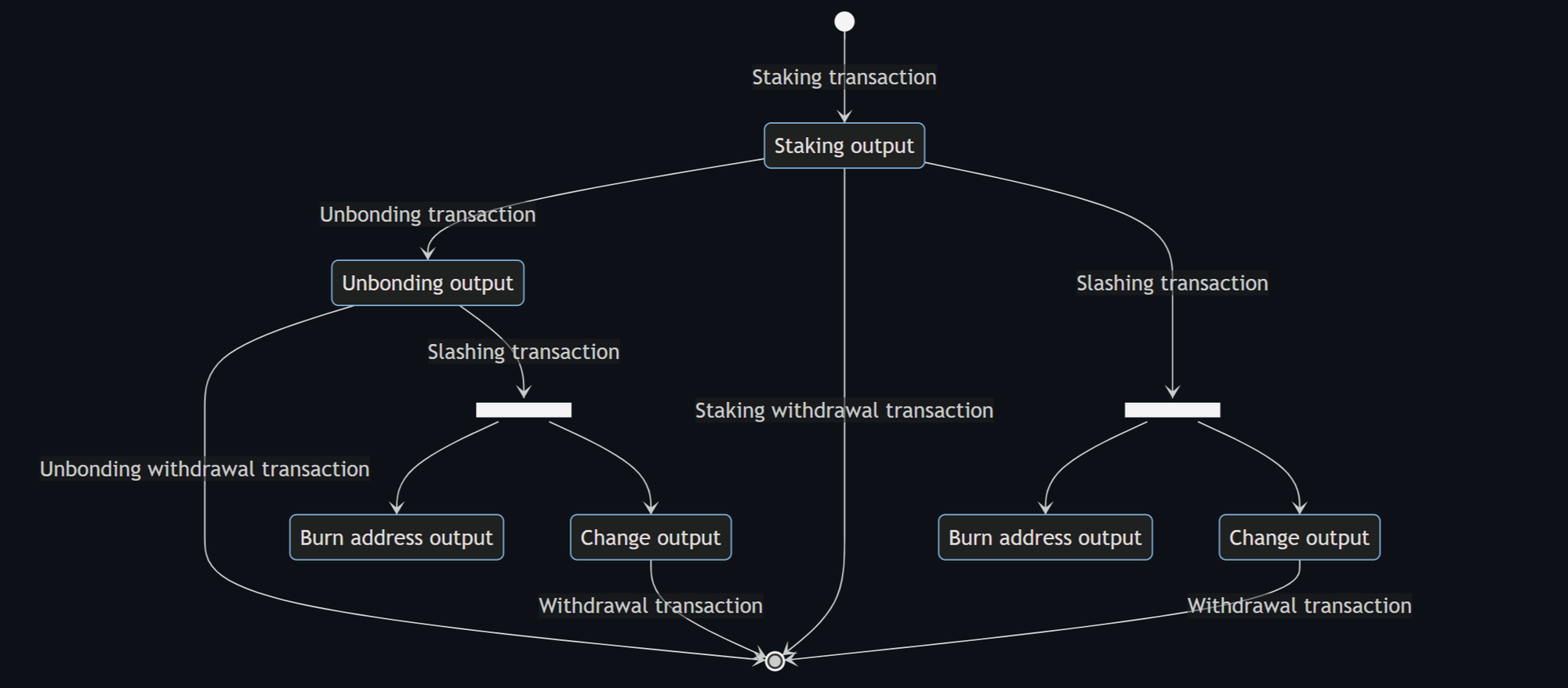

In Babylon's recent Testnet-4, the staking process is divided into three types of transactions: Staking Transactions (Staking Tx), Unbonding Transactions (Unbonding Tx), and Slashing Transactions (Slashing Tx). These transactions generate three corresponding types of Bitcoin outputs: Staking Outputs, Unbonding Outputs, and Slashing Outputs. The conversion process is illustrated in the figure below.

Staking Transaction

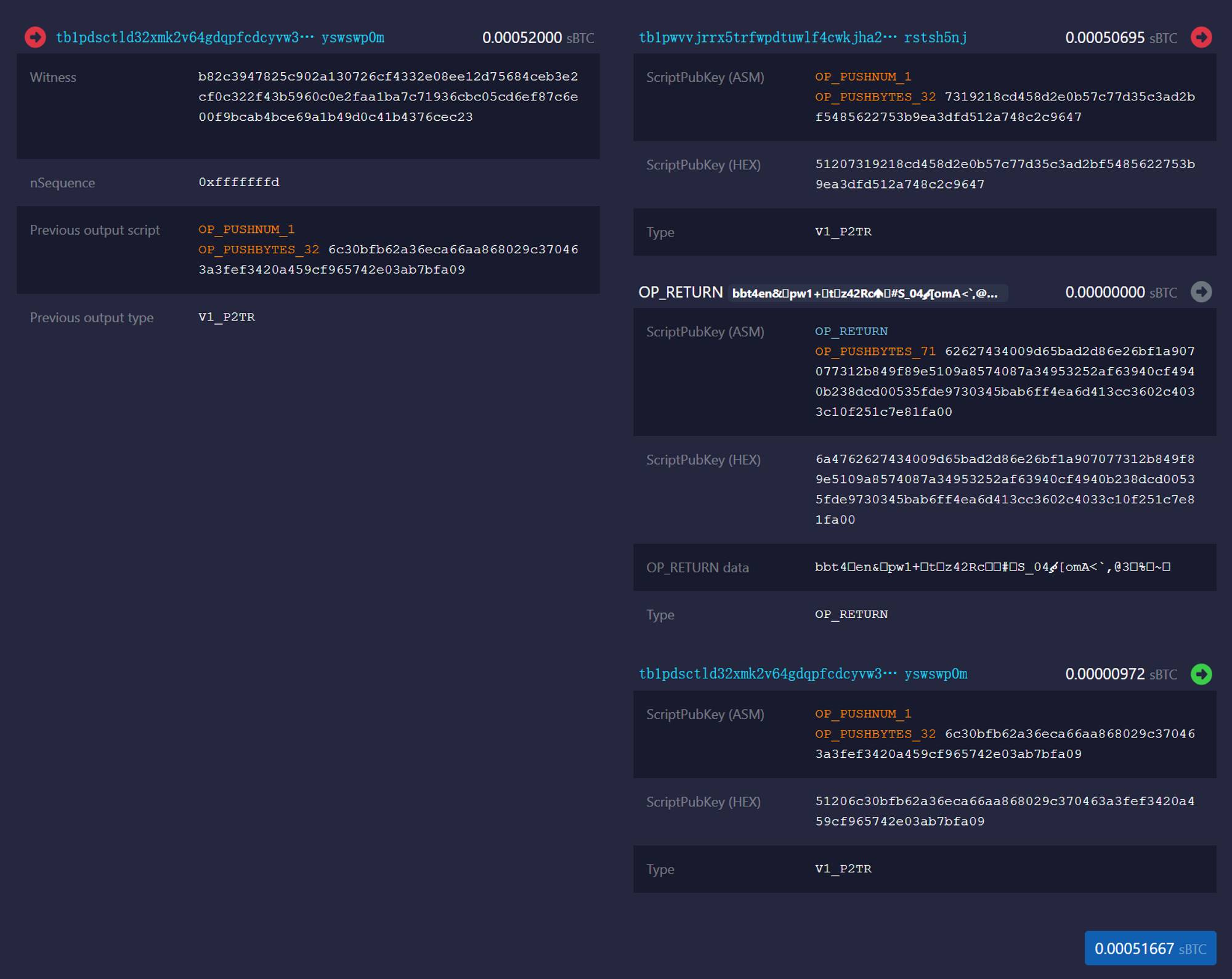

A staking transaction must include two special outputs. One is a Taproot output holding the staked assets, which must contain the BTC staking script defined by Babylon. The other is a zero-value output that stores Babylon-identifiable staking information via OP_RETURN.

The figure below shows an example of a staking transaction, where the first output is the staking output, the second is the OP_RETURN output, and the third is the change output.

Staking Output

A staking output is a Taproot output. As previously discussed in Chakra’s article:

Taproot outputs support two spending methods: key-path spending and script-path spending. Babylon disables the key-path spending by setting the internal key to a "Nothing Up My Sleeve" (NUMS) point, ensuring that staking outputs can only be spent via the script path.

A staking output can be spent through three script paths, corresponding to the process diagram:

1. Timelock Path

The timelock path enables the staking functionality and also serves as an liveness guarantee.

<Staker_PK> OP_CHECKSIGVERIFY <Timelock_Blocks> OP_CHECKSEQUENCEVERIFY

The timelock script locks the staker’s BTC for a certain number of blocks. Since this path does not require any external entities, it provides stakers with a liveness guarantee. Even if the finality provider and covenant committee become inactive, stakers can still reclaim their BTC after the lockup period.

2. Unbonding Path

If BTC is locked by the timelock, how can users exit staking early? Babylon addresses this by introducing the unbonding path.

<StakerPk> OP_CHECKSIGVERIFY

<CovenantPk1> OP_CHECKSIG <CovenantPk1> OP_CHECKSIGADD ... <CovenantPkN> OP_CHECKSIGADD

<CovenantThreshold> OP_GREATERTHANOREQUAL

This path requires not only the staker’s signature but also signatures from more than CovenantThreshold members of the covenant committee. The main reason for introducing the covenant committee is to artificially create an unbonding period, preventing stakers from bypassing penalties via the unbonding path.

3. Slashing Path

To ensure PoS security, slashing is necessary. If a finality provider behaves maliciously, its own and delegated funds must be confiscated to provide economic security. Babylon introduces the slashing path to enable this slashing mechanism.

<StakerPk> OP_CHECKSIGVERIFY

<FinalityProviderPk> OP_CHECKSIGVERIFY

<CovenantPk1> OP_CHECKSIG <CovenantPk1> OP_CHECKSIGADD ... <CovenantPkN> OP_CHECKSIGADD

<CovenantThreshold> OP_GREATERTHANOREQUAL

Before the staking state turns Active, stakers must pre-sign the slashing path transaction to prevent them from withholding signatures to avoid BTC loss when a finality provider acts maliciously. After receiving the staker’s signature, the covenant committee first verifies it, and upon confirmation, releases their own signatures.

In Bitcoin staking, punishable behavior occurs when a finality provider signs two conflicting blocks at the same height. In such cases, any user can obtain the malicious finality provider’s private key via EOTS. Since stakers and the covenant have already pre-signed the slashing transaction, a user who obtains the private key can sign and submit a transaction that uses the slashing path to send part of the staked funds to a burn address as penalty.

OP_RETURN Output

Although Taproot outputs express complex conditions using compact ScriptPubKeys, this makes it challenging to distinguish staking transactions from others on the Bitcoin network. Therefore, it is necessary to disclose staking-related information through alternative means so users can identify slashing transactions based on this data.

Babylon serializes the required disclosure information, embeds it into an OP_RETURN script, and attaches it as another output in the staking transaction. The format is shown below, and the data must correspond to the data in the Taproot script.

type V0OpReturnData struct {

MagicBytes []byte

Version byte

StakerPublicKey []byte

FinalityProviderPublicKey []byte

StakingTime []byte

}

Based on prior transaction snapshots, the OP_RETURN output carries exactly 4+1+32+32+2=71 bytes of valid data. In the figure, the FinalityProviderPublicKey in the staking transaction is f4940b238dcd00535fde9730345bab6ff4ea6d413cc3602c4033c10f251c7e81, belonging to Chakra.

MagicBytes are used to quickly identify staking transactions, while Version is a reserved field for future updates to allow version differentiation.

Unbonding Transaction

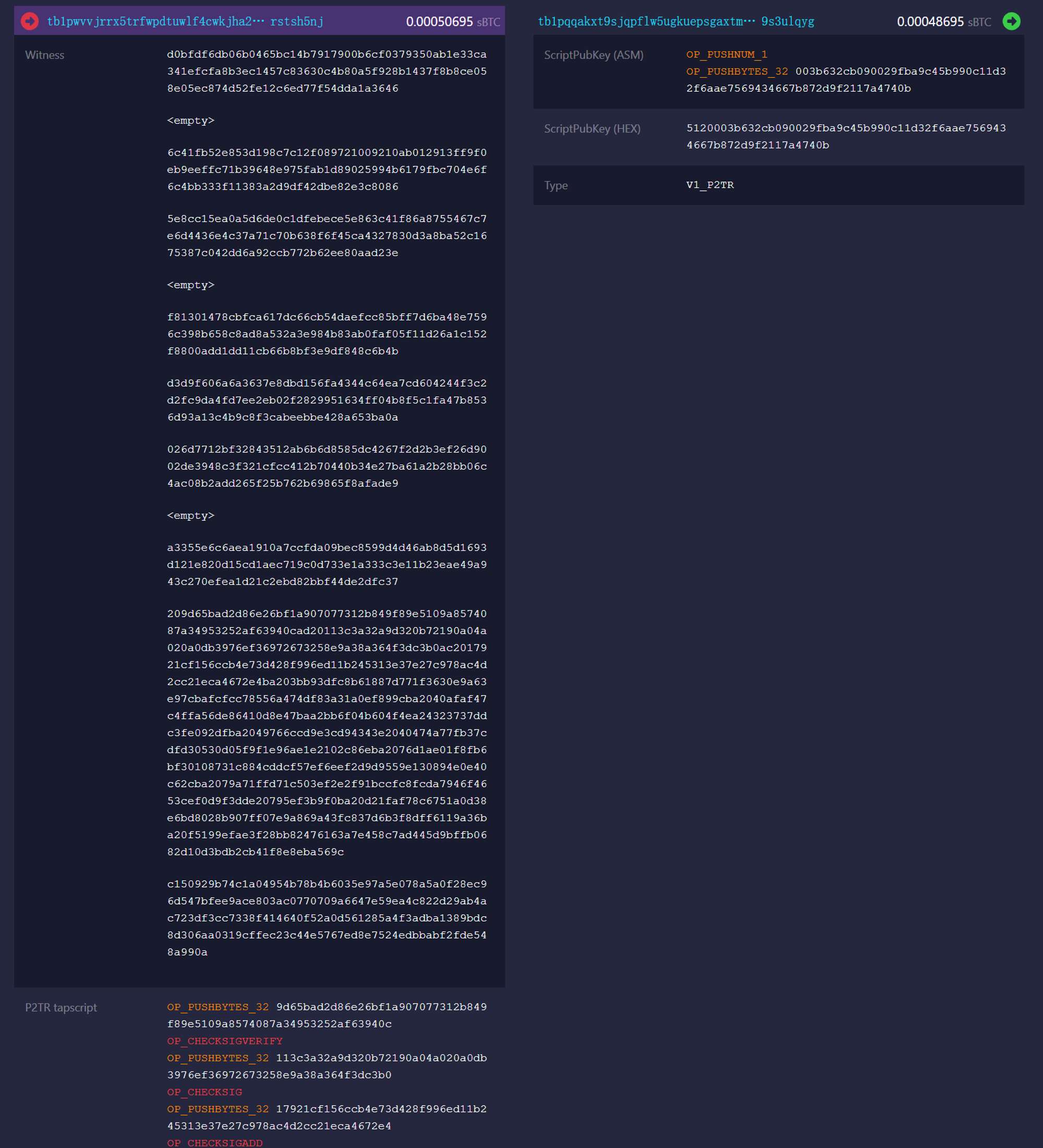

When a staker wishes to unlock their staked BTC early, they can submit an unbonding transaction by spending the unbonding path within the staking output. The unbonding transaction must take a single staking transaction as input and produce a single Taproot output committed to the unbonding script.

Below is a screenshot of an unbonding transaction, corresponding to the previous staking output.

Here, the second-to-last field starting with '20' is the tapscript of the unbonding path, and the one starting with 'c1' is the Merkle proof of the Taproot internal key and the unbonding path, clearly showing the NUMS point 0x50929b74c1a04954b78b4b6035e97a5e078a5a0f28ec96d547bfee9ace803ac0. In the witness field of the unbonding transaction, we can observe the staker’s signature along with signatures from the covenant committee.

An unbonding output can be spent under two conditions: the timelock path and the slashing path—both identical to those in the staking output. At a higher level, the unbonding output acts as an intermediate state designed to prevent stakers from immediately withdrawing their stake and evading penalties, eventually leading to a withdrawal transaction as the final stable state.

Slashing Transaction

A slashing transaction takes either a staking transaction or an unbonding transaction as input, spends via the slashing path in the Taproot script, and produces two outputs. One sends a portion of the staked BTC to a burn address, while the other returns the remaining BTC to the staker.

More strictly, Babylon implements partial confiscation of misbehaving stakes rather than burning all staked BTC at once. This approach offers higher fault tolerance and protects stakers’ interests.

A slashing transaction can only occur with joint signatures from the staker, the covenant committee, and the finality provider. Thus, even if individual parties are compromised, the entire staking system will not collapse. Slashing transactions act as a deterrent, economically discouraging malicious behavior. As long as the penalty for misconduct exceeds any potential gains, participants are incentivized to comply with the rules.

Security Analysis

There are two types of security associated with Babylon:

The first concerns stakers, ensuring that as long as the staker and their delegated finality provider do not engage in malicious behavior, their staked assets will never be slashed.

The second relates to the PoS system itself, guaranteeing that if participants behave maliciously, the protocol must be able to detect and penalize them.

From the Staker's Perspective

For stakers, once BTC is staked via a Babylon staking transaction, there are only three ways the funds can be transferred.

The first is the timelock path, which requires only the user’s own signature to spend. This ensures that even if the FP and Babylon cease operations, stakers can still reclaim their original BTC after the staking period.

The second is the unbonding path, which creates an intermediate unbonding output and allows for a shorter unlocking time, providing stakers with the ability to retrieve their staked funds earlier.

The third is the slashing path—the only one that could potentially harm the staker’s interests. For an external attacker to exploit the slashing path, they would need to simultaneously provide the staker’s signature, the finality provider’s signature, and signatures from more than the threshold number of covenant committee members—an extremely difficult feat. Even if the covenant committee acts maliciously, as long as the finality provider remains honest, the staker’s BTC remains secure.

From the PoS System's Perspective

From the perspective of the PoS system, its security stems from the ability to punish finality providers when they behave maliciously.

Babylon employs the EOTS mechanism: if a finality provider double-signs a block, any user can extract the finality provider’s private key from the two distinct signatures. This enables them to sign and submit a slashing transaction that partially confiscates BTC corresponding to all voting power held by the malicious finality provider.

This slashing mechanism deters malicious behavior by aligning finality providers’ incentives with delivering finality for PoS consensus services connected to Babylon, thereby securing PoS systems with large amounts of staked TVL.

In the future, Chakra will continue collaborating with Babylon to launch a series of staking initiatives, offering users multiple revenue streams while addressing liquidity and interoperability challenges, unlocking Bitcoin’s immense value across all crypto ecosystems.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News