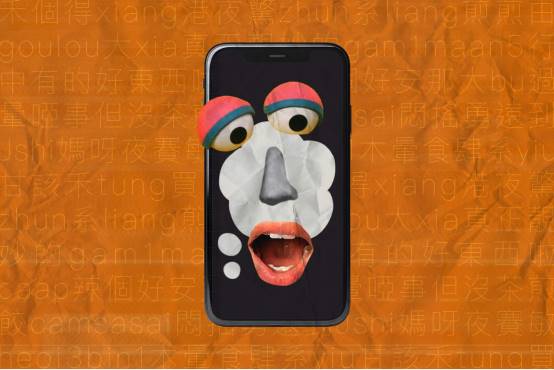

When ChatGPT speaks Cantonese poorly: In the age of AI, are low-resource languages destined for marginalization?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

When ChatGPT speaks Cantonese poorly: In the age of AI, are low-resource languages destined for marginalization?

Behind AI's half-baked Cantonese lies the struggle between language preservation and social resource allocation.

By Anita Zhang

Have you ever heard ChatGPT speak Cantonese?

If you're a native Mandarin speaker, congratulations—you've instantly unlocked the "fluent in Cantonese" achievement. But for those who actually speak Cantonese, the experience might be more confusing. ChatGPT speaks with a strange accent, like someone from outside trying their best to mimic Cantonese.

In an update released in September 2023, ChatGPT gained the ability to "speak" for the first time. On May 13, 2024, the latest model, GPT-4o, was launched. While its voice feature hasn't officially rolled out yet and remains limited to demos, last year's update already revealed a glimpse of ChatGPT’s multilingual speech capabilities.

Many have noticed that ChatGPT’s Cantonese has a heavy accent. Though its intonation sounds natural—almost human—the "human" it mimics is clearly not a native Cantonese speaker.

To verify this and explore the reasons behind it, we conducted a comparative test of Cantonese speech software: tested systems included ChatGPT Voice, Apple Siri, Baidu’s ERNIE Bot, and suno.ai. The first three are voice assistants, while suno.ai is a recently popular AI music generation platform. All four can generate responses in Cantonese—or something close to it—based on prompts.

In terms of pronunciation, both Siri and ERNIE Bot delivered accurate pronunciations, though their replies sounded mechanical and rigid. The other two showed varying degrees of pronunciation errors—often defaulting to Mandarin-like articulation. For example, “影” should be pronounced “jing2” in Cantonese but became “ying”; “亮晶晶,” which should be “zing1,” was read as “jing.”

ChatGPT pronounces “高” in “高楼大厦” as “gao,” whereas it should be “gou1” in Jyutping. Frank, a native Cantonese speaker, pointed out this is a common error among non-native speakers—and one often joked about locally because “gao” is a vulgar term referring to a sexual organ in Cantonese slang. ChatGPT’s pronunciation varies slightly each time; sometimes it correctly says “厦” as “haa6,” other times mispronounces it as “xia”—a sound that doesn’t exist in Cantonese but resembles the Mandarin pronunciation.

Grammatically, the generated text leans heavily toward written formality, only occasionally including colloquial expressions. Word choice and sentence structure frequently switch into Mandarin patterns, producing unnatural phrases such as “买东西” (Mandarin) instead of “买嘢” (Cantonese), or “用粤语来给你介绍一下香港啦” rather than the natural “用粤语同你介绍下香港啦.”

When creating Cantonese rap lyrics, suno.ai produced lines like “街坊边个仿得到,香港嘅特色真正靓妙”—phrases semantically unclear. We asked ChatGPT to evaluate this line, and it noted: “This seems like a direct translation from Mandarin, or a syntactic mix of Mandarin and Cantonese.”

For comparison, when these systems attempt Mandarin, such errors largely disappear. Of course, there are regional variations within Cantonese itself—Guangzhou, Hong Kong, and Macau all have distinct accents and vocabulary. The so-called "standard" Xiguan accent differs significantly from everyday spoken Cantonese in Hong Kong. Yet ChatGPT’s version of Cantonese at best reflects the awkward, half-learned accent of a Mandarin-dominant speaker—a state colloquially described as “唔咸唔淡” (neither salty nor bland).

What’s going on here? Does ChatGPT simply not know Cantonese? It doesn’t outright refuse—it tries, but its attempt is clearly shaped by imagination rooted in a more dominant, institutionally backed language. Could this become a problem?

Linguist and anthropologist Edward Sapir argued that spoken language shapes how people interact with the world. What does it mean when a language cannot assert itself in the age of artificial intelligence? Will our collective imagination of what Cantonese sounds like gradually converge with that of AI?

Languages Without “Resources”

Reviewing OpenAI’s public information, ChatGPT’s voice mode introduced last year relies on three main components: first, the open-source speech recognition system Whisper transcribes spoken words into text; then, the ChatGPT text model generates a response; finally, a Text-to-Speech (TTS) model converts the reply into audio, fine-tuning the pronunciation.

In short, the conversational content is still generated by ChatGPT 3.5’s core model, trained on vast amounts of existing web text—not speech data.

Herein lies a significant disadvantage for Cantonese, which exists predominantly in spoken rather than written form. Officially, written Chinese in Cantonese-speaking regions follows Standard Written Chinese derived from northern dialects—closer to Mandarin than to spoken Cantonese. Meanwhile, written Cantonese (also known as “Cantonese script”), which aligns with spoken grammar and vocabulary, appears mostly in informal contexts like online forums.

This informal writing lacks consistent rules. “About 30% of Cantonese characters, I don’t even know how to write,” said Frank. In online chats, people often just type a character with a similar Mandarin pinyin sound. For instance, the phrase “乱噏廿四” (meaning nonsense), pronounced lyun6 up1 jaa6 sei3, is commonly typed as “乱 up 廿四.” While generally understandable, this further fragments and standardizes written Cantonese inconsistently.

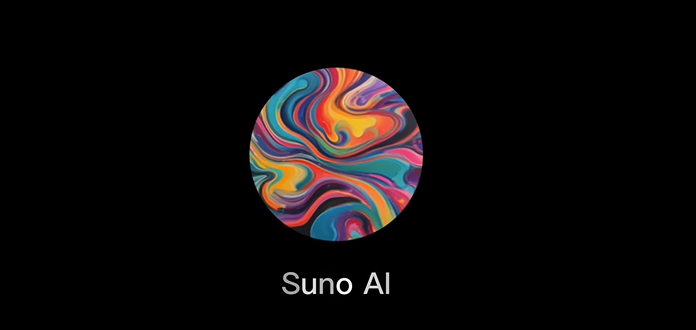

The rise of large language models has highlighted the importance—and potential bias—of training data. But long before generative AI emerged, disparities in data availability across languages had already created deep divides. Most natural language processing (NLP) systems are designed and tested using high-resource languages. Globally, only about 20 languages—including English, Spanish, Mandarin, French, German, Arabic, Japanese, and Korean—are considered “high-resource.”

Despite having 85 million speakers, Cantonese is often treated as a low-resource language in NLP. As a benchmark for deep learning, Wikipedia’s English content compresses to 15.6GB, traditional and simplified Chinese combined reach 1.7GB, while the Cantonese version is only 52MB—a nearly 33-fold difference.

Similarly, in Common Voice—the largest publicly available speech dataset—there are 1,232 hours of “Chinese (China)” recordings, 141 hours of “Chinese (Hong Kong),” and 198 hours labeled as “Cantonese.”

Data scarcity profoundly affects machine performance in natural language processing. A 2018 study found that machine translation fails to produce reasonable results if parallel sentences in the corpus number fewer than 13,000. This also impacts speech recognition accuracy. Whisper (version 2), the open-source model used by ChatGPT Voice, shows a significantly higher character error rate for Cantonese compared to Mandarin.

The model’s textual output reflects the lack of written Cantonese resources—but how do pronunciation and intonation go wrong in ways that shape our listening experience?

How Do Machines Learn to Speak?

Humans have long dreamed of making machines speak—dating back to the 17th century, with early attempts involving organs or bellows pumping air through complex devices simulating lungs, vocal cords, and oral structures. This idea was later adopted by inventor Joseph Faber, who built a talking automaton dressed in Turkish attire—but few understood its purpose at the time.

It wasn’t until household appliances became widespread that giving machines voices sparked broader interest.

After all, coding isn’t natural for most people, and many disabled individuals have been excluded from technology due to communication barriers.

At the 1939 World’s Fair, Bell Labs engineer Homer Dudley unveiled Voder, the earliest known “machine voice.” Unlike today’s mysterious machine learning, Voder’s mechanism was simple and visible: a female operator sat before a keyboard-like device, skillfully pressing ten keys to simulate vocal cord vibrations. She could also use foot pedals to adjust pitch, mimicking cheerful or somber tones. Beside her, a host invited audience members to suggest new words, proving the voice wasn’t pre-recorded.

According to contemporary recordings, The New York Times described Voder’s voice as sounding like “greetings from aliens emerging from the deep sea,” or like a drunken person mumbling unintelligibly. Yet at the time, the technology was astonishing—Voder attracted over five million visitors during the fair.

Early depictions of intelligent robots and alien beings drew inspiration from such devices. In 1961, Bell Labs scientists made the IBM 7094 sing the 18th-century British tune “Daisy Bell”—the first known computer-synthesized song. Arthur C. Clarke, author of *2001: A Space Odyssey*, once visited Bell Labs and heard IBM 7094 sing “Daisy Bell.” In his novel, the supercomputer HAL 9000 learns this very song first. In the film adaptation, as HAL is being shut down and descends into confusion, he begins singing “Daisy Bell,” his voice shifting from eerily human to mechanical growls.

Since then, speech synthesis has evolved over decades. Before neural network technologies matured in the AI era, concatenative synthesis and formant synthesis were the most common methods—many current voice functions still rely on them, such as screen readers. Formant synthesis dominated early development. Like Voder, it uses parameters such as fundamental frequency, voicing, and frication to generate unlimited sounds. A key advantage: it can produce any language. As early as 1939, Voder could speak French.

Of course, it could also speak Cantonese. In 2006, Huang Guanneng, a Guangzhou native pursuing a master’s degree in computer software theory at Sun Yat-sen University, considered developing a Linux browser for visually impaired users. During this process, he encountered eSpeak, an open-source formant-based speech synthesizer. Thanks to its linguistic flexibility, eSpeak quickly saw practical applications. In 2010, Google Translate began adding read-aloud features for numerous languages—including Mandarin, Finnish, and Indonesian—using eSpeak.

November 24, 2015, Beijing, China—a robotic arm writes Chinese characters with a brush.

Huang decided to add support for his mother tongue—Cantonese—to eSpeak. But due to technical limitations, the synthesized speech had a noticeable patchwork quality. “It’s like learning Chinese not through pinyin, but through English phonetic spelling—it sounds exactly like a foreigner trying to speak Chinese,” Huang explained.

So he developed Ekho TTS. Today, this speech synthesizer supports Cantonese, Mandarin, and even rarer languages like Zhao’an Hakka, Tibetan, Elegant Speech, and Taishanese. Ekho uses concatenative synthesis—commonly called “cut-and-paste”: human speech is prerecorded and stitched together during output. This ensures more accurate single-character pronunciation, and if common phrases are fully recorded, the result sounds more natural. Huang compiled a Cantonese pronunciation chart of 5,005 syllables—recording them all takes two to three hours.

The advent of deep learning revolutionized this field. Deep-learning-based speech synthesis learns mappings between text and speech features from massive voice corpora, without relying on predefined linguistic rules or prerecorded units. This technology dramatically improved the naturalness of synthetic voices, often matching human speech. It can clone someone’s voice and speaking style from just seconds of audio—exactly the method used by ChatGPT’s TTS module.

Compared to formant and concatenative methods, these systems drastically reduce upfront labor costs—but demand far greater volumes of paired text-speech data. For example, Google’s 2017 end-to-end model Tacotron requires over 10 hours of training data to achieve good audio quality.

To address resource scarcity in many languages, researchers have proposed transfer learning: train a general model on high-resource languages, then adapt it to low-resource ones. To some extent, the transferred patterns retain characteristics of the original dataset—just as a person’s first language influences how they learn a second. In 2019, the Tacotron team demonstrated a model capable of cloning a speaker’s voice across languages. In demos, when an English speaker “spoke” Mandarin, although pronunciation was correct, a strong “foreign accent” remained evident.

A commentary in the *South China Morning Post* noted that Hong Kong writers use Standard Chinese in formal writing to ensure mutual understanding among all Chinese speakers. They must use “他们” (“taa1 mun4”)—a word almost never used in spoken Cantonese—to mean “they.” In contrast, Cantonese uses “佢哋” (keoi5 dei6), which is entirely different in pronunciation and spelling.

On the principle of universal solutions for general problems, the latest GPT-4o model pushes further. OpenAI explains that they trained an end-to-end model across text, vision, and audio, with all inputs and outputs processed by a single neural network. How it handles different languages remains unclear, but its cross-task generalization appears stronger than ever before.

But the interplay between Cantonese and Mandarin complicates things further.

In linguistics, “diglossia” refers to situations where two closely related varieties coexist in a society—one prestigious, typically used in official settings, the other serving as a vernacular or dialect.

In China, Mandarin holds the highest status—used in formal writing, news broadcasting, education, and government. Regional dialects like Cantonese, Hokkien (Taiwanese), and Shanghainese occupy lower tiers, primarily used for daily oral communication in homes and local communities.

Thus, in Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macau, Cantonese serves as most people’s mother tongue for daily conversation, while formal written language follows Mandarin-based Standard Written Chinese.

Despite many similarities, key differences—like “他们” vs. “佢哋”—can lead to confusion and difficulty when transferring knowledge between the two, making AI adaptation harder.

The Gradual Marginalization of Cantonese

“Concerns about Cantonese’s future are far from unfounded. Language decline can happen rapidly, fading within one or two generations—and once a language begins to die, it’s nearly impossible to revive.” — James Griffiths, *Speak Mandarin*

It may seem that poor speech synthesis performance in Cantonese stems merely from technological limits in handling low-resource languages. When faced with unfamiliar words, deep learning models generate auditory illusions. But after hearing ChatGPT’s voice output, Professor Tan Lee from the Department of Electronic Engineering at The Chinese University of Hong Kong offered a different perspective.

A Cantonese opera performance at the Yau Ma Tei Theatre

Tan Lee has been researching speech and language technologies since the early 1990s, leading the development of several Cantonese-centered spoken language systems now widely applied. His 2002 CU Corpora—a Cantonese speech corpus co-developed with his team—was the largest of its kind globally at the time, containing recordings from over 2,000 speakers. Many companies and research institutions, including Apple’s first-generation speech recognition system, purchased access to this dataset.

In his view, ChatGPT’s Cantonese speech performance is “not good—mainly unstable, with unsatisfactory voice quality and pronunciation accuracy.” But this poor performance isn’t due to technical limitations. In fact, many existing Cantonese-capable voice generation products on the market perform far better. He was so skeptical of online videos showing ChatGPT’s speech that he initially thought they were deepfakes: “If you’re building a speech generation model and deliver something like this, it’s basically unprofessional—career suicide.”

Take CUHK’s own systems as examples: the most advanced ones now produce voices indistinguishable from real humans. Compared to dominant languages like Mandarin and English, AI-generated Cantonese only lags slightly in emotional expressiveness in personalized, everyday scenarios—such as parent-child conversations, counseling sessions, or job interviews—where it may sound colder.

“But strictly speaking, there’s no technical difficulty here. The issue lies in societal and resource choices,” Tan Lee emphasized.

Compared to 20 years ago, speech synthesis has undergone revolutionary changes. By today’s standards, CU Corpora’s data volume is “less than one ten-thousandth” of modern datasets. Commercialization of speech technology has turned data into a market commodity—data firms can provide massive custom datasets on demand. Moreover, thanks to advances in speech recognition, the lack of paired text-speech data for Cantonese—as a spoken language—is no longer a critical bottleneck. Thus, labeling Cantonese a “low-resource language” is, in Tan Lee’s view, outdated.

Therefore, he argues, machine performance in Cantonese reflects market and commercial priorities, not technical capability. “Imagine if everyone in China started learning Cantonese tomorrow—it would definitely take off. Or suppose Hong Kong integrates further with the mainland, and one day education policy bans Cantonese in schools, requiring only Mandarin. Then the story would be completely different.”

The accent revealed by deep learning—“you are what you eat”—mirrors the real-world compression of Cantonese.

Huang Guanneng’s daughter recently entered middle kindergarten in Guangzhou. Though she spoke only Cantonese at home, within a month of school, she became fluent in Mandarin. Now, even in daily interactions with family and neighbors, she defaults to Mandarin—only switching back to Cantonese with her father, “because she wants to play with me, so she follows my preference.” To Huang, ChatGPT’s Cantonese sounds just like his daughter now: forgetting certain words and substituting Mandarin equivalents, or guessing pronunciations based on Mandarin.

This reflects decades of neglect—and active exclusion—of Cantonese in Guangdong. A 1981 document from the Guangdong Provincial Government declared, “Promoting Mandarin is a political task,” especially in a linguistically diverse province with frequent internal and external exchanges, aiming to “ensure all public spaces in major cities use Mandarin within three to five years, and普及 Mandarin in all schools within six years.”

Frank, who grew up in Guangzhou, recalls vividly that foreign films broadcast on public TV channels had subtitles but no dubbing—except Cantonese films, which required Mandarin dubbing to air. Against this backdrop, Cantonese has steadily declined. School-led bans on Cantonese sparked fierce debates over its survival and cultural identity. In 2010, large-scale “Support Cantonese” protests erupted online and offline in Guangzhou. Media reports likened the struggle to the scene in the French novella *The Last Lesson*, arguing that decades of cultural radicalism had shriveled a once-thriving linguistic branch. For Hong Kong, Cantonese is a vital carrier of local culture—Cantopop and Hong Kong cinema have shaped global perceptions of its social life.

In 2014, an article on the Education Bureau website referred to Cantonese as “a Chinese dialect not recognized as an official language,” sparking intense backlash, ultimately forcing officials to apologize. In August 2023, Hong Kong’s pro-Cantonese group “Hong Kong Language Academy” announced its dissolution. Founder Chan Lok-hang later noted the ongoing pressure on Cantonese in Hong Kong: the government actively promotes “Putonghua-medium instruction” (PMI) in Chinese classes, though public concern has “slowed its pace.”

These incidents underscore Cantonese’s significance to Hong Kongers—but also reveal the sustained pressure it faces locally: its lack of official status, vulnerability, and the ongoing tension between government and civil society.

Jyutdict, an online Cantonese dictionary

Voices Not Represented

The illusion of language isn’t unique to Cantonese. On Reddit and OpenAI forums, users worldwide report similar issues with ChatGPT’s non-English speech:

“Its Italian speech recognition is excellent—always understands and speaks fluently, like a real person. But oddly, it has a British accent, like a Brit speaking Italian.”

“As a Brit, I’d say it has an American accent. I hate that, so I avoid using it.”

“Same with Dutch—so annoying, like it’s trained on English phonemes.”

Linguists define accent as a particular way of pronunciation, influenced by geography, social class, and other factors, often reflected in tone, stress, or word choice. Interestingly, historically discussed accents usually stem from non-native speakers applying their mother tongue habits to English—like Indian, Singaporean, or Irish accents—highlighting global linguistic diversity. But AI reveals a reverse phenomenon: dominant languages distorting and invading regional ones.

Technology amplifies this invasion. A February Statista report highlighted that while only 4.6% of the world speaks English natively, it dominates 58.8% of online text—giving it disproportionate influence online. Even counting all English speakers (about 1.46 billion), they represent less than 20% of the global population. That means roughly four out of five people cannot understand most online content—and struggle to make English-dominant AI work for them.

Some African computer scientists found ChatGPT frequently misinterprets African languages, offering shallow translations. For Zulu (a Bantu language with ~9 million speakers), its performance is “hit-or-miss, laughable.” For Tigrinya (spoken mainly in Eritrea and Ethiopia, ~8 million speakers), queries return gibberish. This raises concerns: lacking AI tools capable of recognizing African names and locations could exclude Africans from global economic systems—e-commerce, logistics, information access, automated production—denying them economic opportunities.

Using a single language as a “gold standard” also skews AI judgment. A 2023 Stanford study found AI incorrectly flagged many TOEFL essays (written by non-native speakers) as AI-generated, while rarely doing so for native English students’ work. Another study showed automatic speech recognition systems make nearly twice as many errors with Black speakers compared to White speakers—and these errors stem not from grammar, but from “phonetic, prosodic, or rhythmic features”—in short, “accent.”

More disturbingly, in simulated court trials, large language models recommended death sentences more frequently for speakers of African American Vernacular English than for those speaking Standard American English.

Some warn that deploying current AI technologies uncritically—without addressing underlying technical flaws—could have serious consequences. For instance, automated speech recognition is already used in courtroom transcription, where records of accented or non-native speakers may be distorted, leading to unfair rulings.

Going further: will people abandon or alter their accents to be understood by AI? In reality, globalization and socioeconomic development are already causing such shifts. Frank, now a graduate student in North America, shared that her Ghanaian classmate described the current linguistic landscape in his country: written texts are almost exclusively in English—even personal letters. Spoken language increasingly mixes English words, causing locals to gradually forget native African vocabulary and expressions.

In Tan Lee’s view, people are now obsessed with machines. “Because machines do well now, we desperately try to talk to them”—this reverses the purpose. “Why do we speak? Not to turn speech into text, or to get a machine-generated reply. In the real world, we speak to communicate.”

He believes technology should aim to improve human-to-human communication, not human-to-computer interaction. Under this vision, “we can easily identify many unresolved issues: someone can’t hear—due to deafness or distance; someone doesn’t understand the language; adults can’t speak children’s language, children can’t speak adults’.”

Today, many fun language technologies exist—but do they truly enhance communication? Are they embracing diversity, or pushing everyone closer to the mainstream?

While people celebrate ChatGPT’s cutting-edge breakthroughs, basic applications still fail to benefit from them. Tan Lee still hears incorrect pronunciations in airport announcements: “The primary goal of communication is accuracy—and that’s not being met. That’s unacceptable.”

A few years ago, due to limited personal capacity, Huang Guanneng stopped maintaining the Android version of Ekho. But after a pause, users reached out asking him to restore it. He learned that Android now has no free Cantonese TTS option available.

By today’s standards, Ekho uses outdated technology—but retains unique value. As a local independent developer, Huang infused it with personal linguistic insight. His Cantonese dictionary includes seven tones, including a seventh tone not recognized in the Hong Kong Linguistic Society’s Jyutping system. “The word ‘烟’ has different tones in ‘抽烟’ versus ‘烟火’—first tone and seventh tone respectively.”

When compiling the pronunciation guide, he consulted Jyutping developers, who told him younger Hong Kongers no longer distinguish between the first and seventh tones, causing the latter to fade. Yet Huang chose to preserve it—not due to standardization, but personal memory: “Native Guangzhou speakers can still hear it, and it’s still widely used today.”

Just hearing that tone, a true local knows—you’re either from here, or you’re not.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News