Unveiling the Federal Reserve's "money printing" tactics: understanding the deeper reasons behind debt issuance

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Unveiling the Federal Reserve's "money printing" tactics: understanding the deeper reasons behind debt issuance

Uncontrolled, ever-increasing, and unapologetic.

Author: James Lavish

Translation: TechFlow

"Printing money" seems simple, yet it's confusing. If the Federal Reserve can print more dollars to cover any government spending, why sell bonds to the public at all? The answer is simple—but requires a bit of critical thinking.

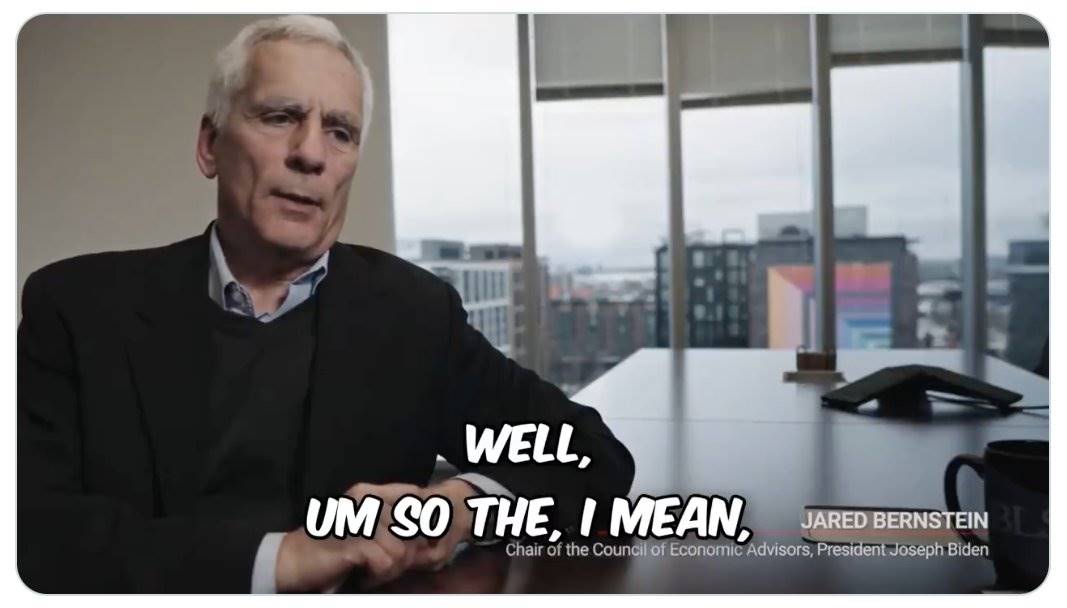

If you were on Twitter last week, you may have seen video clips of Jared Bernstein, Chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers—the body that advises the President on economic policy—"explaining" bonds.

Even so, he appears genuinely confused about the basic concept of national debt and how it works. To be fair, these ideas are indeed difficult to grasp—so let’s break them down simply and clearly.

Basics of Money Supply

To understand "printing money," we must first understand the basics of money—or more precisely, the basics of "money supply." We’ll keep this explanation high-level and accessible.

Narrow Money

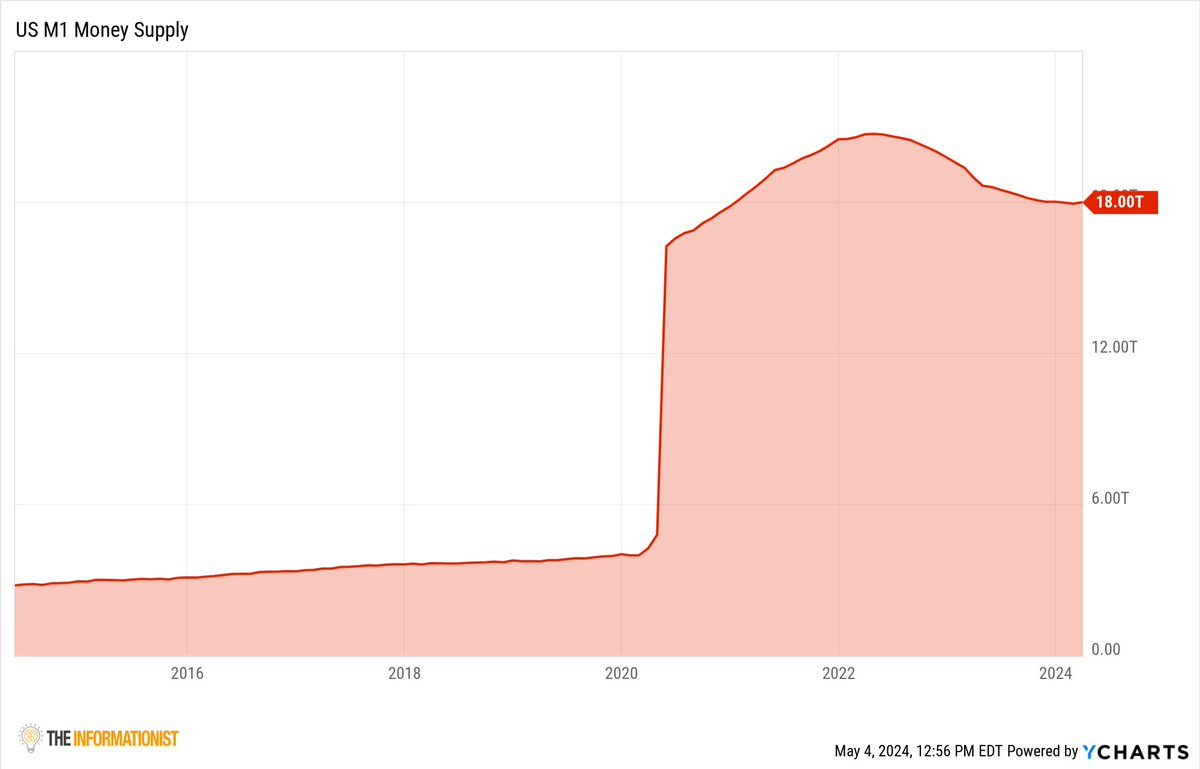

The narrowest measure of money supply is known as M0 ("em-zero"). This includes only physical currency in circulation and cash reserves held by banks. M0 is often called the monetary base. One level up, we have M1. M1 includes all of M0 plus demand deposits (checking accounts), and any outstanding traveler’s checks. Demand deposits refer to liquid bank account balances that customers can withdraw at any time—essentially checking and savings accounts.

Banks don’t keep all their cash in vaults. They use risk analysis to estimate how much physical cash each branch needs under normal conditions without a bank run. The rest exists only as digital entries—zeros and ones—in their ledgers.

In any case, M1 includes only cash that can be physically withdrawn (including traveler’s checks)—nothing more. Thus, M1 is commonly referred to as narrow money. Here is the dollar amount of M1:

I know what you’re thinking: What exactly happened in 2020 that caused the M1 money supply to skyrocket? You guessed it: money printing. We’ll get back to that shortly, but first, let’s unpack the next layer of money supply—broad money.

Broad Money

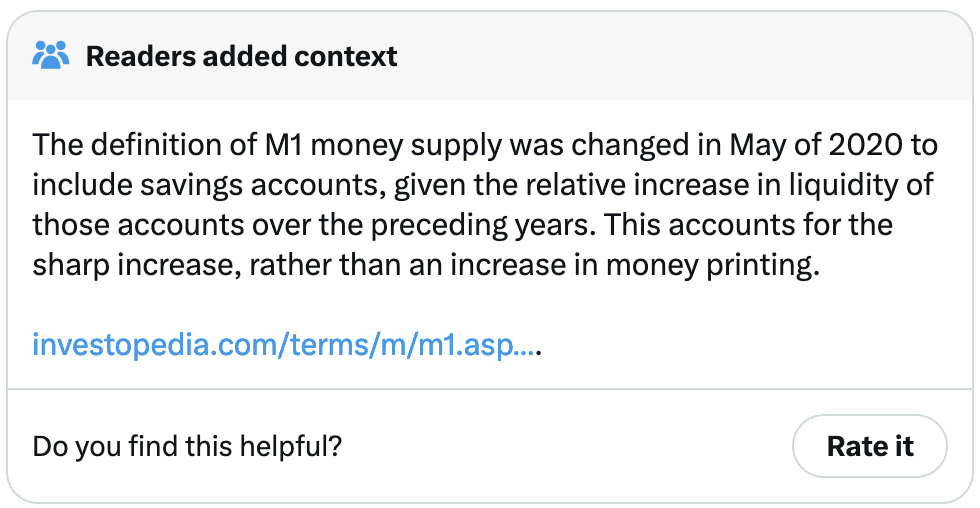

Expanding our scope slightly, M2 includes all of M1 plus money market savings deposits, time deposits under $100,000 (such as certificates of deposit and money market funds). In other words, M2 encompasses all funds held in cash equivalents and in liquid or semi-liquid accounts.

Here is the current dollar amount of M2. As you can see, the expansion of M2 after 2020 was gradual, taking time to “trickle through” into individual accounts.

Why? Because of the Cantillon Effect. Named after 18th-century economist Richard Cantillon, the Cantillon Effect describes how those who receive new money first—such as banks, governments, or financial institutions—benefit, while others experience delayed effects.

Now, let’s address the confusion Jared Bernstein encountered when describing U.S. Treasury bonds—a system he clearly doesn’t fully understand himself.

Basics of National Debt

At its most basic definition, U.S. Treasury debt consists of bonds issued by the American government. It’s no different from bonds issued by Apple, Microsoft, or Tesla—except here, it’s a nation (or company) borrowing money from those who buy the bonds.

What happens when you borrow money? You pay interest to the person who lent it to you—just like paying interest to a bank on a mortgage. You borrow money from a bank to buy a house, and you pay the bank interest on that loan. We all know the government has been borrowing heavily lately because it’s running deficits (spending exceeds tax revenue), and it borrows to cover the gap—increasing the U.S. public debt.

How much has the U.S. borrowed—and how much does it owe to everyone who lent it money?

You won’t believe it—$34.6 trillion!

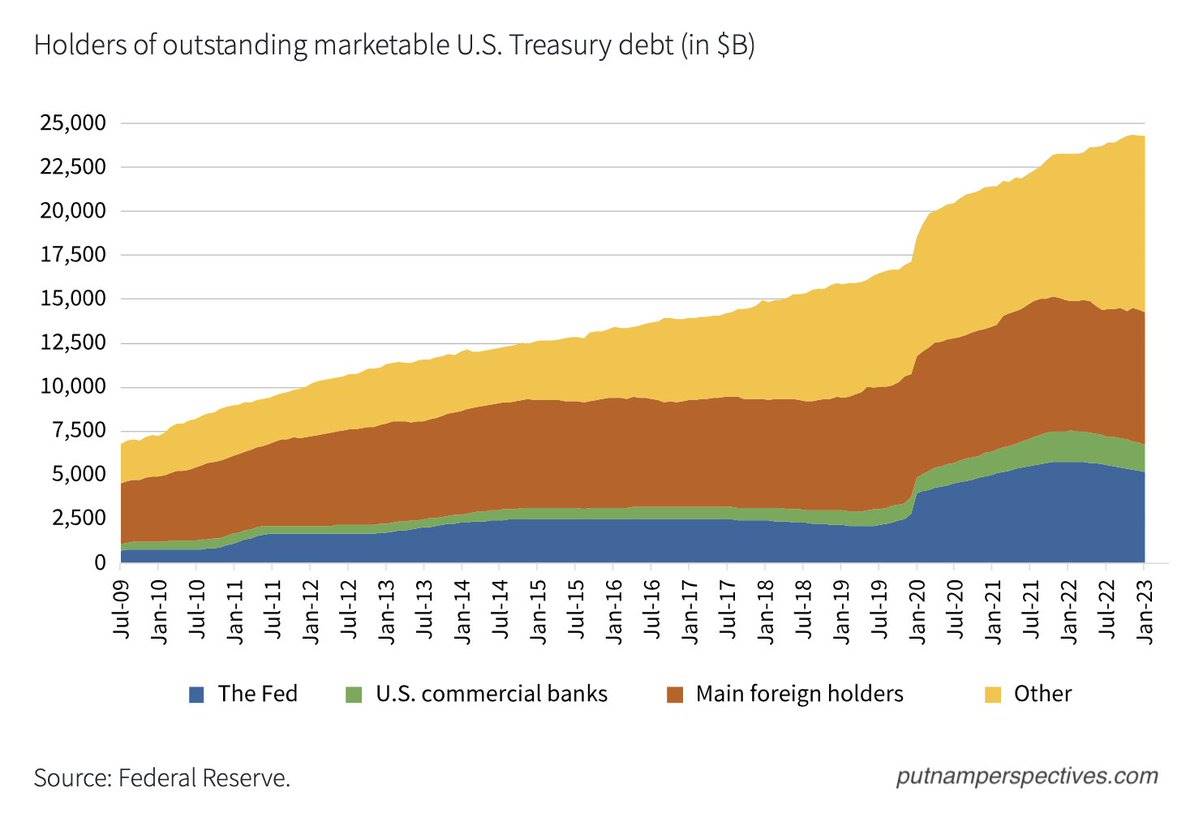

So who is buying all these bonds? Who is lending the U.S. so much money?

Essentially, you and I, along with others, directly purchase bonds in our IRAs, 401(k)s, and personal accounts, and indirectly through mutual funds, money market funds, U.S. banks, foreign central banks (like the Bank of Japan, People’s Bank of China, etc.), and even the Federal Reserve itself buys them.

You might wonder—how can they possibly hold so much U.S. debt? Let me walk you through it step by step.

How Money Is "Printed"

This involves Quantitative Easing (QE) and Quantitative Tightening (QT).

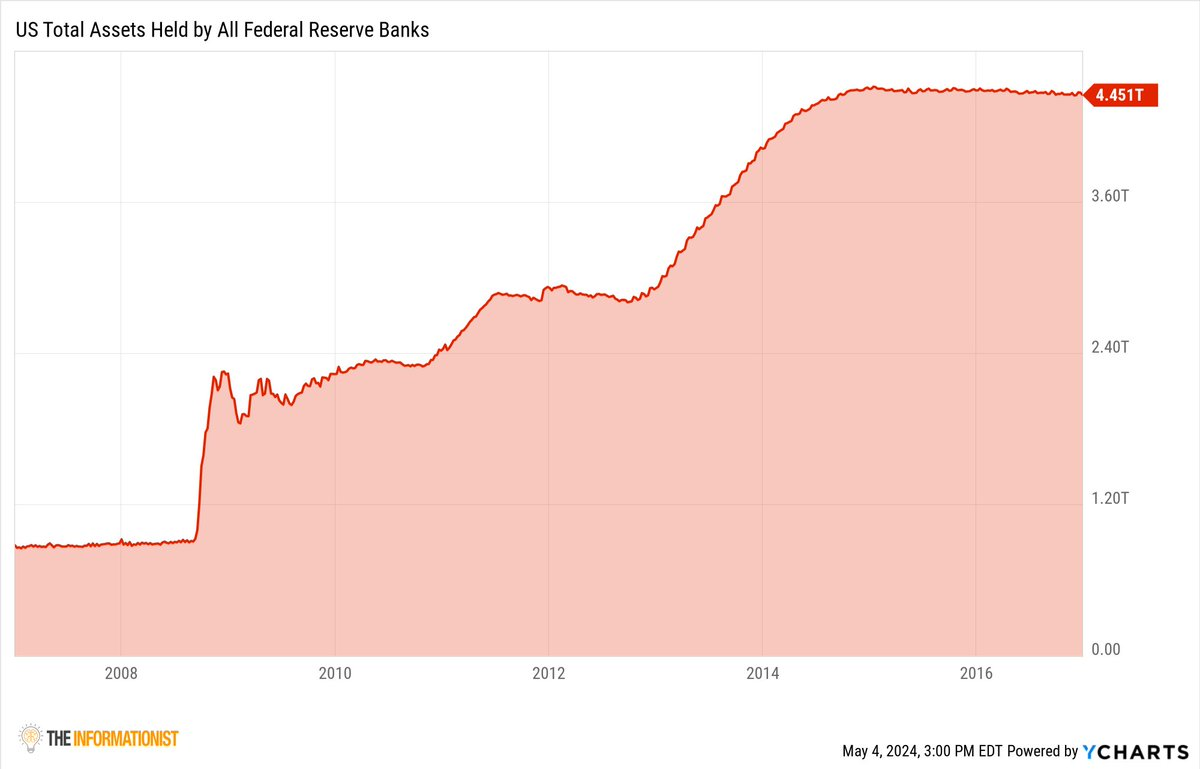

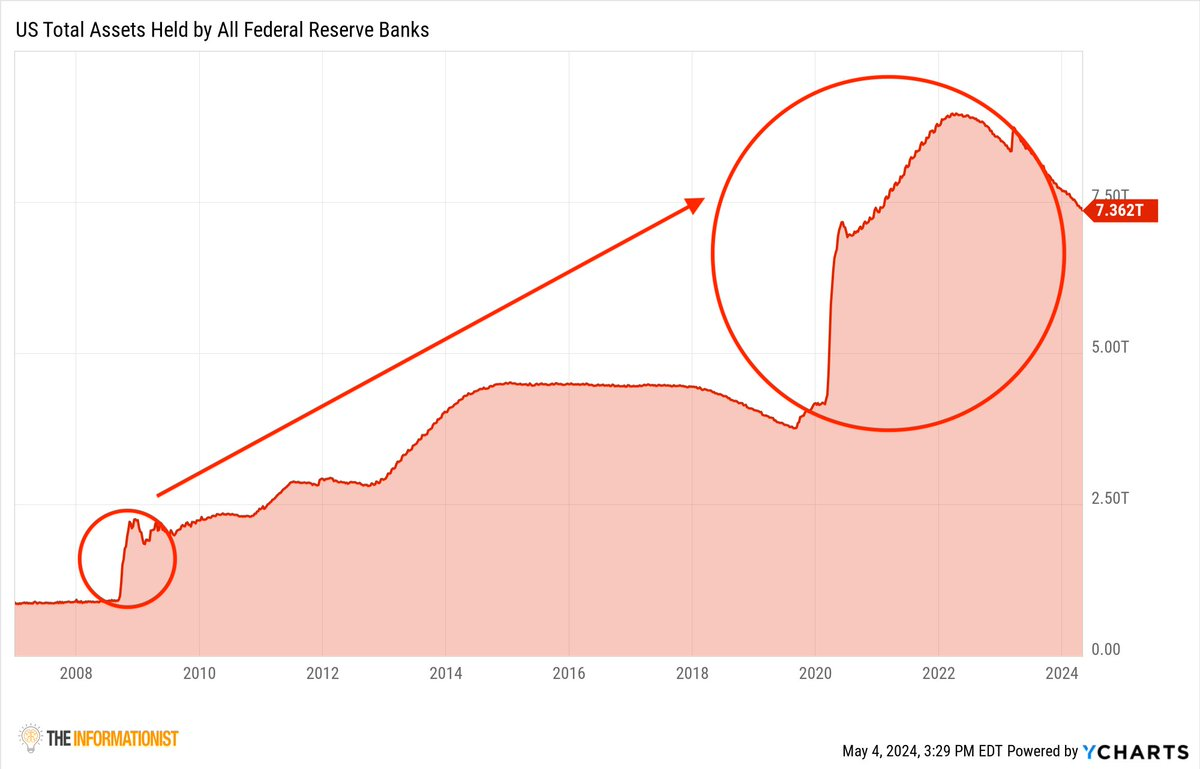

During financial crises or recessions—such as the Global Financial Crisis—we saw the Fed use QE like a shotgun, recklessly buying U.S. Treasuries and MBS (mortgage-backed securities). QT is when the Fed sells them back into the market.

During the GFC-era QE, the Fed purchased over $1.5 trillion in such assets within just a few years—and continued adding more for several years afterward.

Fast forward to 2020, when markets froze due to pandemic lockdowns. The Fed pulled out its cash "bazooka." This meant injecting over $5 trillion in just two years—compare that to 2009.

But how did they do it?

As the U.S. central bank, the Federal Reserve has a unique ability to create money. When the Fed uses QE to purchase securities like Treasury bonds, it does so by creating bank reserves out of thin air—a digital process of money creation. Here’s how it works:

-

The Fed announces its intention to buy securities and specifies the amount.

-

Primary dealers (large intermediary banks) buy these securities on behalf of the Fed in the open market.

-

After the purchase, the Fed credits newly created money to the primary dealer’s reserve account and adds the Treasury bonds to its own balance sheet.

-

This process increases total bank reserves, directly injecting liquidity into the banking system.

In essence, primary dealers act as brokers and settle the transaction—sending the newly created funds to the sellers of Treasuries and delivering the bonds to the Fed. More cash then enters the system.

Imagine you’re playing Monopoly, and all the money has already been distributed and is in play. Then, a new player joins the game, bringing Monopoly money from his own home set, and starts buying properties. Now, he’s introduced new currency that wasn’t there before—he’s expanded the money supply. As a result, Park Place and Boardwalk become more expensive. This is exactly what the Federal Reserve does when it conducts QE and buys bonds in the open market.

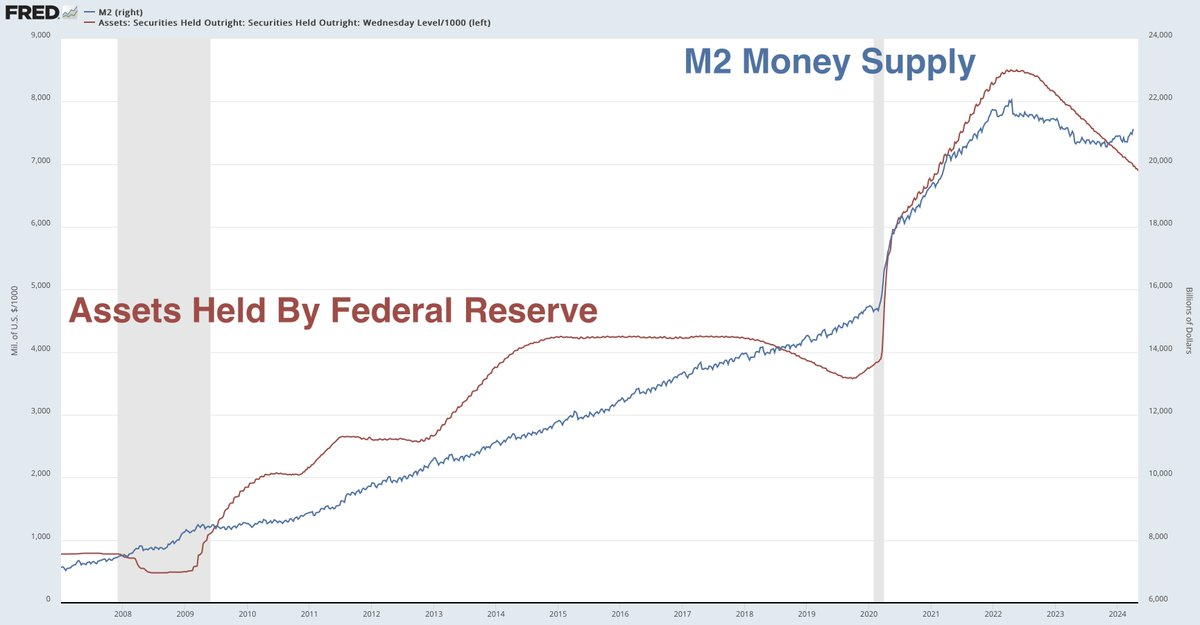

The Fed adds new money into the market that wasn’t there before, injecting liquidity. Notice how the M2 money supply (the blue line) rises in tandem with the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet. This is textbook money printing.

So why don’t we skip the entire QE and Treasury bond system and just print money directly? If we did, we’d essentially become what’s known as a "banana republic." Openly and excessively printing money to fund government deficits leads to hyperinflation. Imagine a world where the Treasury (effectively Congress) could spend whatever it wants, and the Fed simply prints however many dollars are needed to cover it.

Uncontrolled. Endless. Unchecked.

With a rapidly expanding money supply, prices would rise exponentially (Park Place and Boardwalk would sell for millions, billions, trillions). People would lose confidence in the dollar as a store of value—and eventually, as a medium of exchange. Streets would be flooded with dollars because you’d need a wheelbarrow full just to buy anything, and prices would change by the minute.

(If you think this is exaggerated, take a look at Venezuela or Lebanon.)

This would lead to loss of confidence, chaos, and a rapid descent into hyperinflation—the collapse of the dollar. The Fed and Treasury would go to great lengths to obscure and distract from an infinite money printer.

They would sell bonds.

Even if they’re selling them to themselves.

If the country’s top economist is confused by this system, no wonder everyone else is too.

And so, the show goes on.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News