Deconstructing Internet Giants: The Ultimate 10,000-Word Guide to the Encryption Game

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Deconstructing Internet Giants: The Ultimate 10,000-Word Guide to the Encryption Game

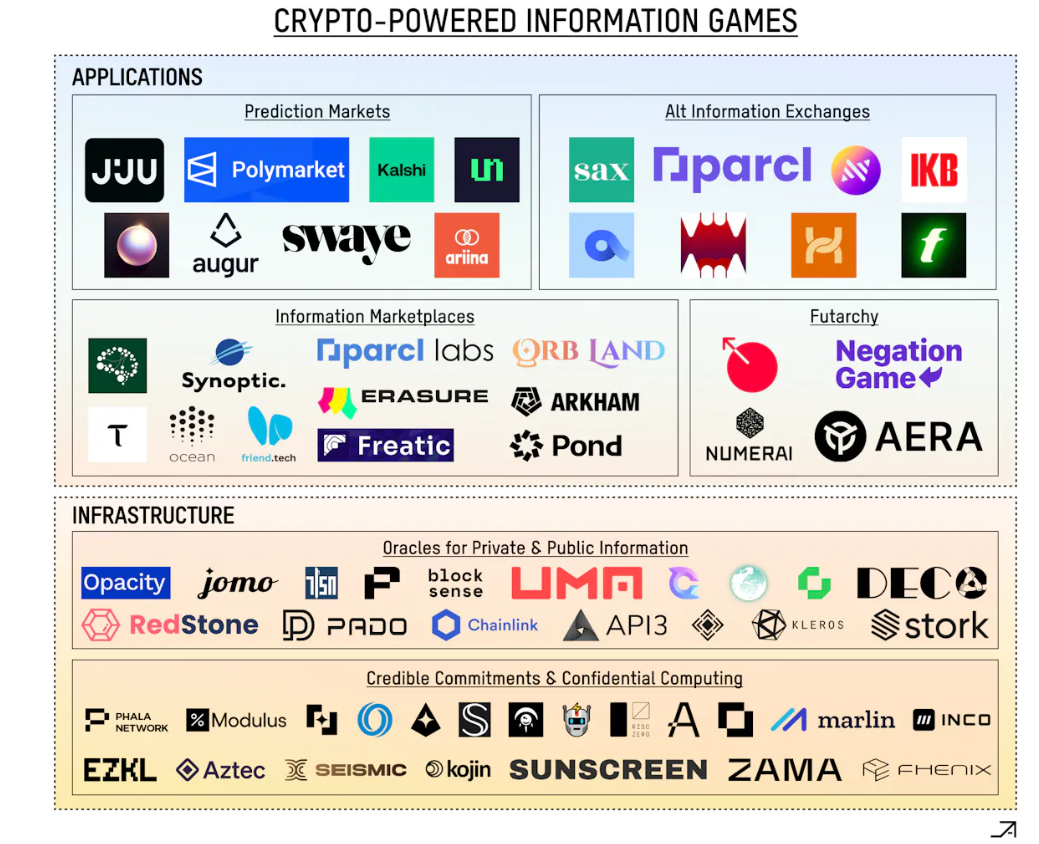

This article covers the infrastructure necessary for creating encrypted information games and realizing their full potential.

Author: Benjamin Funk

Translation: Frank, Foresight News

Our brains, books, and databases are both recipients and creators of humanity's ever-growing tendency to generate data. The internet, as the latest development in this long evolution, produces and stores approximately 250 trillion gigabytes of data every day. While it’s easy to be awed by this number, individual data points themselves hold little value. They are like scattered pieces of a vast puzzle, requiring careful collection, processing, and contextualization to become valuable information.

Many of today’s internet giants center their entire business models around this process, with Google being the most successful. Their workflow is simple: extract vast amounts of valuable raw materials—personal data from billions of people, often referred to as “digital waste”—and feed them through proprietary algorithmic pipelines to predict individuals’ likely choices. The more data Google extracts and processes into insights about us, the deeper the insights they can offer advertisers, leading those advertisers to bid higher in Google’s ad auctions in an attempt to convert us into customers.

Through these processes, Google generates $240 billion in advertising revenue annually. While Google intentionally excludes humans from this loop, there exists another way to generate and profit from valuable information—one that may be even more powerful. By treating humans as players and gamifying the processes of information creation, search, and speculation, we tap into our intrinsic desire to participate. From sports betting to MEV (Maximal Extractable Value), to social deduction games like Among Us, we are naturally drawn to "information games" centered on competition and coordination, where skillfully hiding and revealing information is key.

Some information games are purely for entertainment. But as we will see, others can be used to generate and monetize new, valuable information, becoming foundational pillars for next-generation products and business models.

However, information games have always had one fatal flaw: trust. Specifically, players must trust that others won’t share or exploit information in ways that violate the game’s rules. If a crewmate in an Among Us game could turn into an impostor mid-game, or if a block producer (miner) could submit an incorrect block root yet still get it accepted by validators, no one would want to play anymore. To solve this trust problem, we’ve historically turned to trusted third parties to create and moderate our information games.

For low-risk games like Among Us, this works fine. But limiting game creation and mediation to centralized entities restricts the scope and experimental exploration of the information games we can play, thereby constraining the types of information we can collect, utilize, and monetize.

In short, because we haven’t yet found a way to maintain fairness and trustworthiness in decentralized environments, many potential information games haven’t even been attempted.

Programmable blockchains and new cryptographic primitives are now solving this issue by enabling us to create and coordinate information games at scale without needing permission, third-party trust, or mutual trust among participants.

In turn, crypto-powered information games can rapidly increase the quantity and quality of information globally, enhancing our collective decision-making capabilities and unlocking efficiency gains equivalent in scale to global GDP. Imagine globally accessible prediction markets used to allocate massive pools of internet-native capital. Or a game allowing individuals to pool their private health data and earn rewards whenever new discoveries arise from its use—all while preserving their privacy.

However, as this article will show, crypto-centric information games may not yet be ready for such high-stakes applications. But by experimenting today with smaller, more engaging information games, teams can focus on attracting players and building trust before scaling up to create more profitable information markets and monetizing them.

From prediction markets to game theory, oracles, and networks of trusted execution environments (TEEs), this article will explore the design space of these crypto-based information games and introduce the infrastructure necessary to unlock their full potential.

Permissionless Markets: A Prerequisite for Information Games

From future-scale applications to information-market-focused ones, blockchains allow developers to build customizable, automated financial tools that support permissionless, unstoppable markets. Now, anyone can create mechanisms to incentivize, coordinate, and settle exchanges of value and information. This highlights the critical role blockchains play in enabling rapid experimentation on how best to configure games to maximize value for all participants.

It’s extremely difficult to convince centralized intermediaries to adapt at this pace or allow their users to participate in such experiments. Therefore, permissionless markets will become the medium through which fringe theories and cutting-edge research papers are implemented. We’re already seeing this in prediction markets, where theoretical strategies to address liquidity issues—such as automated market makers—are being realized as CPMMs (constant product market makers) on cryptocurrency networks and tested with real money.

Permissionless markets are key enablers for better tools to generate new information and monetize its value.

Information-Producing Information Games

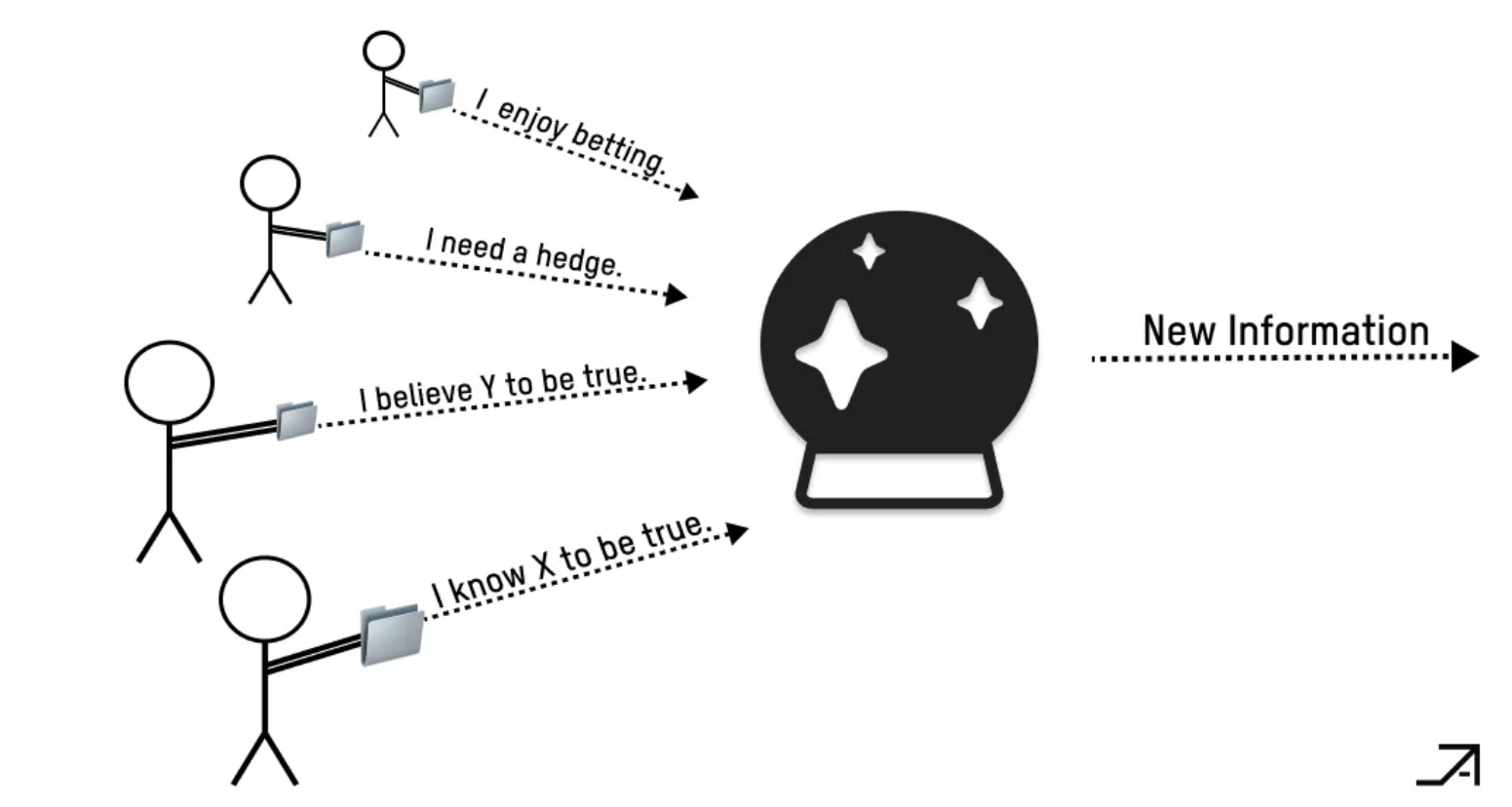

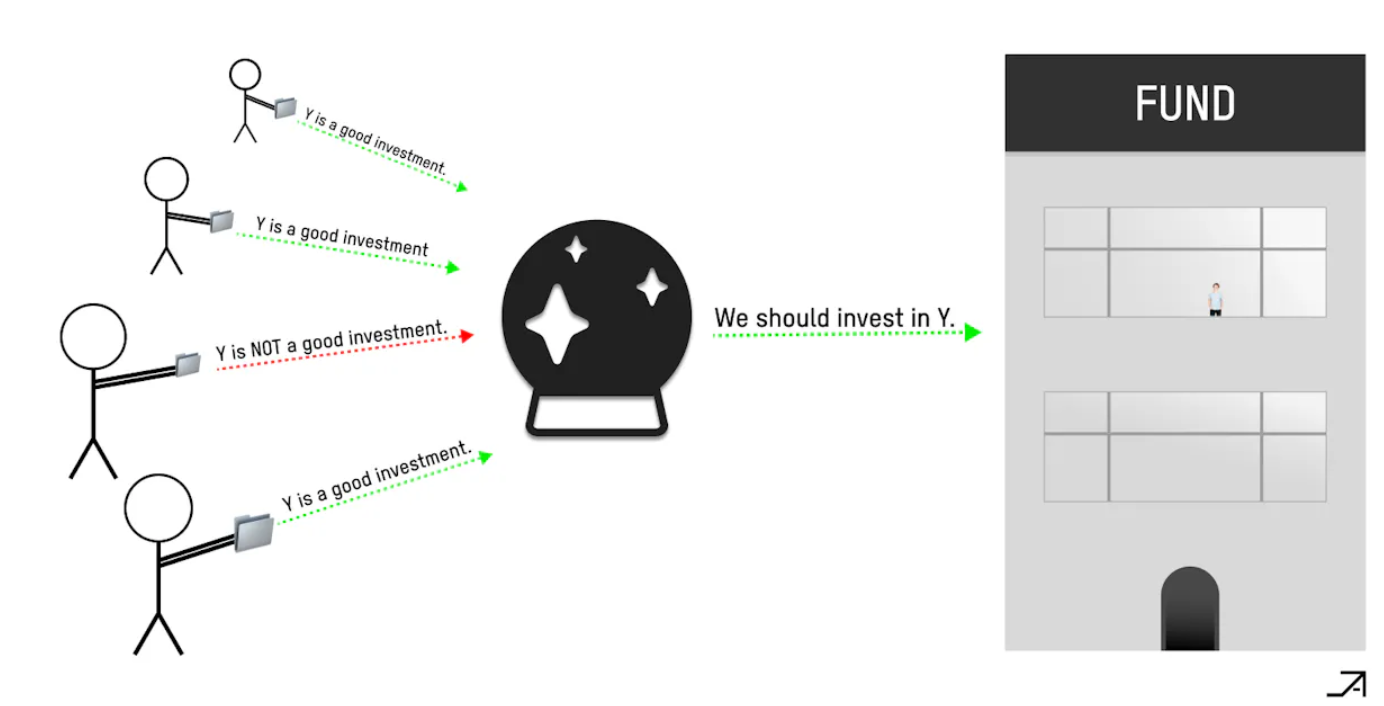

Many information games produce new information that players use to make better decisions.

These games create incentives to extract raw materials—public and private data—from people, databases, and other sources, then aggregate this data through optimal information-producing machines: markets and algorithms. Ideally, during this aggregation, new information emerges and is monetized by helping other players make good decisions. For example, an investment DAO might use results from prediction markets to decide whether to invest in a new startup.

The games and tools leveraged by information game designers vary depending on the type of information they aim to generate, giving us a vast design space to explore different challenges and opportunities.

But let’s begin with the most actively developed and discussed information game today—the prediction market.

Game 1: Prediction Markets as Tools for Generating Information

One of the most popular information games in crypto (and beyond) is the prediction market. Polymarket, the leading global prediction market, has facilitated over $400 million in cumulative trading volume (and growing rapidly).

Prediction markets work by incentivizing players to bet real money—such as cryptocurrency—on the outcomes of various events. This requirement of personal financial risk ("skin in the game") helps ensure participants are genuinely committed to their predictions. As traders act on their insights—buying underpriced outcome shares and selling overpriced ones—the market dynamically adjusts. These price movements reflect increasingly accurate collective estimates of event probabilities, effectively correcting any initial mispricing.

The more people participating, especially those with diverse but relevant public and private knowledge, the more accurately prices reflect the truth. Ultimately, prediction markets harness the “wisdom of the crowd” by using financial risk to drive accurate information aggregation.

Unfortunately, prediction markets face several key challenges, many of which boil down to scalability issues.

Bottleneck of Truthful Information

Keynesian beauty contests—where judges try to pick what others will pick—are not unique to prediction markets. However, here their negative impact is more pronounced because the goal of prediction markets is precisely to generate accurate information. Moreover, unlike traditional financial markets, where profit maximization primarily drives behavior, bettors in prediction markets are more susceptible to personal beliefs, political leanings, or vested interests in certain outcomes. Thus, they may be willing to incur financial losses within the market if their bets align with personal values or external incentives.

Furthermore, the more people treat a market or algorithm as a source of truth, the greater the incentive to manipulate it. This mirrors problems seen on social media platforms.The more people trust the information products generated by social media platforms, the stronger the incentives to manipulate them for profit or socio-political gain.

Some players might even leverage the signals and incentives created by prediction markets to reprice collective beliefs and encourage coordinated action. For instance, imagine a government using a form of "quantitative easing" to influence prediction markets on critical issues like climate change or war. By buying large quantities of shares in related prediction markets, they could shift financial incentives toward desired outcomes. Perhaps they believe systemic risks from climate change are underestimated, so they heavily buy the "no" shares in a market predicting climate improvement by 2028. This move might encourage more climate-tech startups to develop technologies, giving them an informational edge when betting on "yes" shares, accelerating the path to solutions.

While the above factors have been shown to negatively affect information quality, some argue manipulation actually improves market accuracy because manipulators act as noise traders, allowing informed participants to profit by betting against them.

Thus, we can infer that the above issues stem from insufficient numbers of well-funded, informed traders capable of correcting the market.Allowing these informed traders to borrow and short could be a key mechanism to make these markets more efficient.

Additionally, in longer-duration markets, informed traders struggle more to counteract manipulation, as manipulators have more time to reflexively influence market sentiment and actual outcomes. Implementing markets with shorter information credibility windows could increase trust in the game (thus improving information quality) while also making gameplay more engaging.

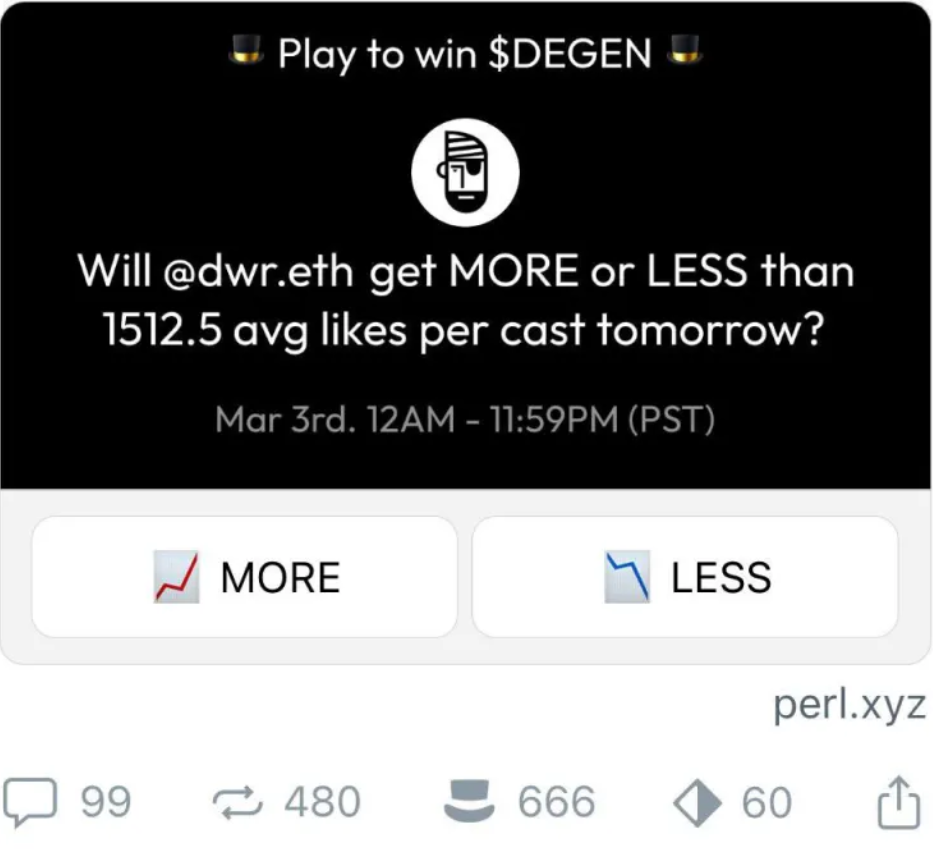

We’ve also seen early signs that players enjoy information games where information credibility windows can be manipulated. Perl, then the top account on Farcaster, favored this model and built an in-app platform to speculate on user engagement. Prediction markets like “Will @ace or @dwr.eth (co-founders of Perl and Farcaster respectively) get more likes tomorrow?” were launched, and the kind of “trolling” football teams and fans anticipate began.Only here, the game is asynchronous, and the metric is likes rather than ‘Touchdown’ (Foresight News note: typically used to describe scoring in American football, occurring when the offense carries the ball into the opponent’s end zone and grounds it). While Perl’s games intentionally degraded the quality of information produced by prediction markets, a fascinating meta-game emerged—coordinating to resolve prophecies beneficial to certain individuals.

Prediction-based games could reduce manipulation and boredom by using shorter, possibly renewable rounds. Yet in low-risk games, allowing manipulation can enhance fun and become an integral part of gameplay.

Finding the Right Arbiters and Oracles

Another challenge for prediction markets lies in resolution—how to correctly determine outcomes. In many cases, we can rely on reputation- and collateral-backed oracles connected to off-chain data sources. To address this, prediction market designers can leverage game-theoretic and cryptographic oracles to cover broader topics, including players’ private information.

Game-theoretic oracles, also known as Schelling-point oracles, assume that participants (or nodes) in a network will independently converge on a single answer or outcome they believe others will also choose, even without direct communication. Pioneered by Augur and later advanced by UMA, this concept encourages honest reporting by rewarding participants based on how close their answers are to the “consensus,” deterring collusion.

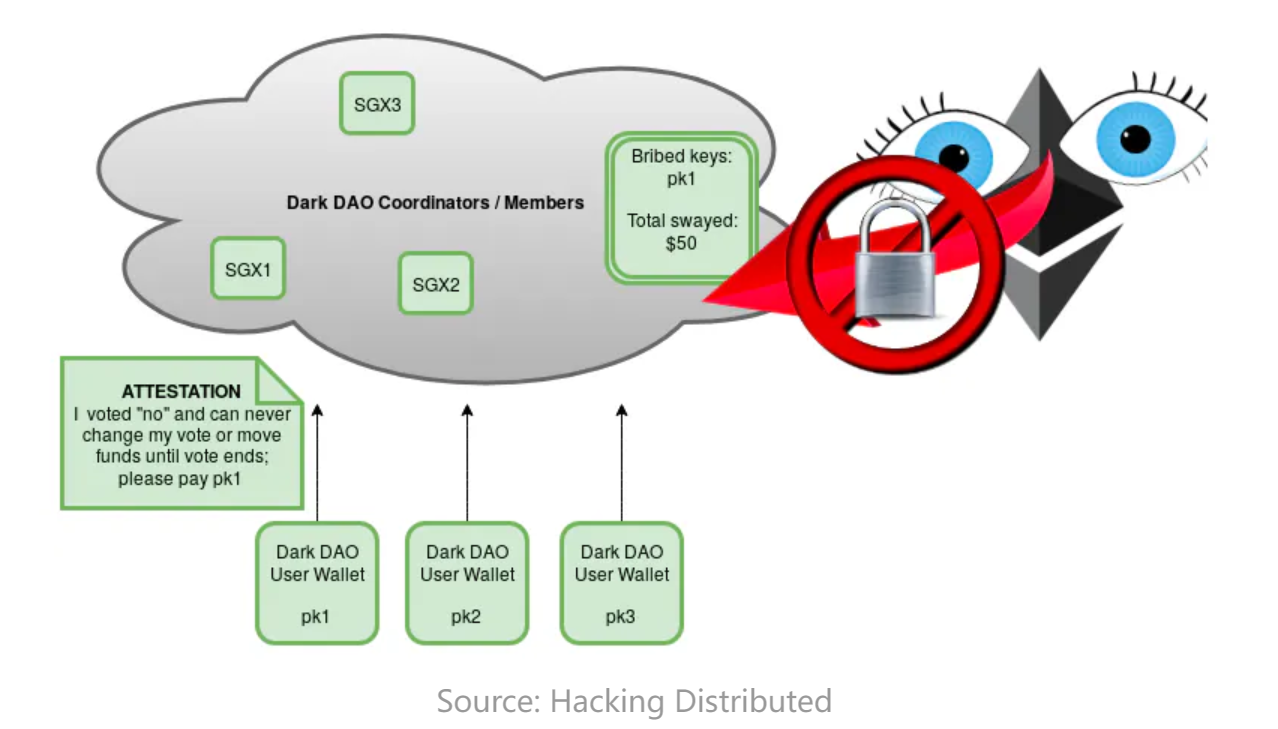

However, significant challenges remain in making these oracles reliable for small-player-bet resolutions, where identifying and communicating with each other poses collusion risks. While cryptography is touted as a key tool to prevent voter collusion, it can also be used to enable collusion and disrupt prediction markets. We see this in DarkDAO’s potential to use Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) for programmatic bribery and price manipulation coordination. One team working to balance these incentives is Blocksense, which uses secret committee selection and encrypted voting to prevent collusion and bribery.

We can also tackle oracle challenges by leveraging on-chain data. In MetaDAO, players are rewarded for correctly predicting how specific proposals will affect the price of its native token. This price is provided via Uniswap V3 positions, serving as an oracle for the token’s value.

Yet these oracles still have limitations in resolving markets based on public data. If we could resolve markets based on private data, we could unlock entirely new types of prediction markets.

We can use the outcomes of information games themselves as oracles—a method for resolving markets based on private data. Bayesian markets are one such example, applying principles of Bayesian inference to derive bettors’ own beliefs about their private information by having them bet on others’ beliefs. For instance, creating a market where people bet on “how many people are satisfied with their lives” reveals bettors’ own beliefs about others’ life satisfaction. Thus, we can draw accurate conclusions about players’ private information—truths otherwise unverifiable.

Another solution involves clever cryptography to “import” data from private Web2 APIs via oracles. Some existing oracles are showcased in the “Public and Private Information Oracles” section of the market map. Using these oracles, prediction markets can be created around players’ private information, incentivizing holders of private data to verifiably resolve specific prediction markets in exchange for trading fees from participants betting on them. More broadly, the ability to securely access richer off-chain personal data and bring it on-chain can serve as an identity primitive, helping us more effectively identify, incentivize, and match players in information games, guiding necessary information to make these games more relevant to players.

Innovations in oracle design will expand the range of data available to resolve prediction markets, broadening the design space for information games around private information.

Liquidity Bottleneck

Attracting liquidity into prediction markets is difficult. First, these are binary markets—players bet “yes” or “no” on a topic, receiving either a fixed monetary reward or nothing. Thus, the value of these shares fluctuates dramatically with minor changes in the underlying asset price, especially near expiration. Predicting short-term price movements becomes crucial but highly challenging. To manage the significant risks from sudden shifts, traders must employ sophisticated, constantly adjusted strategies to handle unexpected volatility.

Moreover, as prediction markets expand into more topics and extend timeframes, attracting liquidity becomes harder. The further markets stray from politics and sports and the longer their duration, the less advantage people feel they have in betting. Consequently, fewer participants lead to lower-quality information.

Prediction markets inherently face these liquidity issues because forming prices requires mining private information and betting on it—both costly activities. Participants need compensation for their effort and assumed risks (including information gathering and capital lockup costs). This compensation usually comes from those willing to accept worse odds, perhaps for entertainment (e.g., sports betting) or hedging (e.g., oil futures), helping drive substantial liquidity and volume. However, narrow-topic prediction markets offer lower commercial appeal, resulting in weaker liquidity and trading volume.

Economic Improvements: Subsidies and Diversification

We can borrow ideas from traditional finance and existing information games to address these issues.

Notably, we can adopt the concept of “overlay” mentioned by Hasu in “The Predicament of Prediction Markets.” In gambling tournaments, an “overlay” resembles subsidized prize pools added by house operators to encourage participation—an extra value boost that lowers entry costs, making tournaments more attractive and increasing participation from both novices and experts.

Just as overlays in gambling tournaments stimulate player engagement by boosting potential returns, subsidies in prediction markets incentivize participation by lowering barriers and making involvement financially appealing. Subsidies also act as beacons, attracting diverse perspectives and insights from both informed and uninformed traders who can profit by correcting errors. Teams implementing this strategy must systematically identify and engage potential subsidy providers, crafting markets around their needs to secure necessary liquidity.

Similarly, a “fund-like” structure could be implemented to achieve temporal and thematic diversification, increasing liquidity across a broader range of questions and time horizons. For example, many companies might find value in markets predicting how specific lawsuits resolve.These companies could lend capital to legal experts, enabling them to diversify across wide-ranging markets, then reward them based on performance over time, reducing participation costs for legal experts.

In such setups, traders could borrow funds to provide market-making, with loan amounts parameterized based on information demand and the trader’s reputation on the subject. This could be combined with management fees serving as additional “overlays” for each market.

For liquidity providers, exposure would come from traders motivated to correctly bet on these markets, diversified across baskets of numerous unrelated assets with varying maturities. While principal-agent issues must be considered, this system could increase the scale of liquidity offered and the diversity of pools allocating it. Additionally, the quality and variety of information goods could improve, while generating new information about traders’ skills and knowledge across markets—accelerating returns for liquidity providers through reputation byproducts.

When the value players can generate from information is substantial, integrating composable financial markets (like lending and liquidity mining) into gameplay can become a key tool for lowering entry barriers.

User Experience Improvements: Simpler Interfaces and Flexible Incentives

The current exchange-centric UX design of prediction markets and limited reward types may deter those preferring alternative interfaces and incentive structures, further limiting liquidity. For bettors, there are many interesting ways to improve prediction market quality, all focused on increasing accessibility and reach for different player types.

First, we can improve usability by integrating prediction markets into larger social platforms. Perl and Swaye demonstrated this by tapping into Farcaster’s data, eliminating the need for users to open separate apps. Information game designers can then identify and guide players into markets they’re particularly suited for (e.g., top contributors in the /nyc-politics channel).

We could also experiment with expanding the types of rewards given to bettors and lowering their capital requirements. This might include rewarding attestations or broadening financial incentives to include “in-app utilities” or equity represented by points or tokens.

While monetary incentives are important for prediction markets, some literature suggests virtual currencies can also produce prediction markets of comparable quality. Practically, this tells us we can flexibly assume the type of “skin in the game” bettors are willing to risk and exert effort for.

Additionally, different market mechanisms could make the experience more “poll-like,” further reducing friction and entry barriers. A study by Cambridge University evaluated this hypothesis and found that in markets with low trading activity, wide bid-ask spreads, and quick resolution, polling mechanisms produced more accurate results than prediction markets. The study also found that combining poll-based prediction games with monetary incentives from prediction markets yielded higher accuracy than pure prediction market prices. Furthermore, to address potential stagnation, polls could be periodically “refreshed” via push or pull systems, incentivizing dynamic replication of information based on new inputs.

Crypto information games used to exclude everyone except the most hardcore enthusiasts. Now, with lower costs, improved usability, and richer data, we have the opportunity to develop more diverse, mass-accessible games targeting specific audiences.

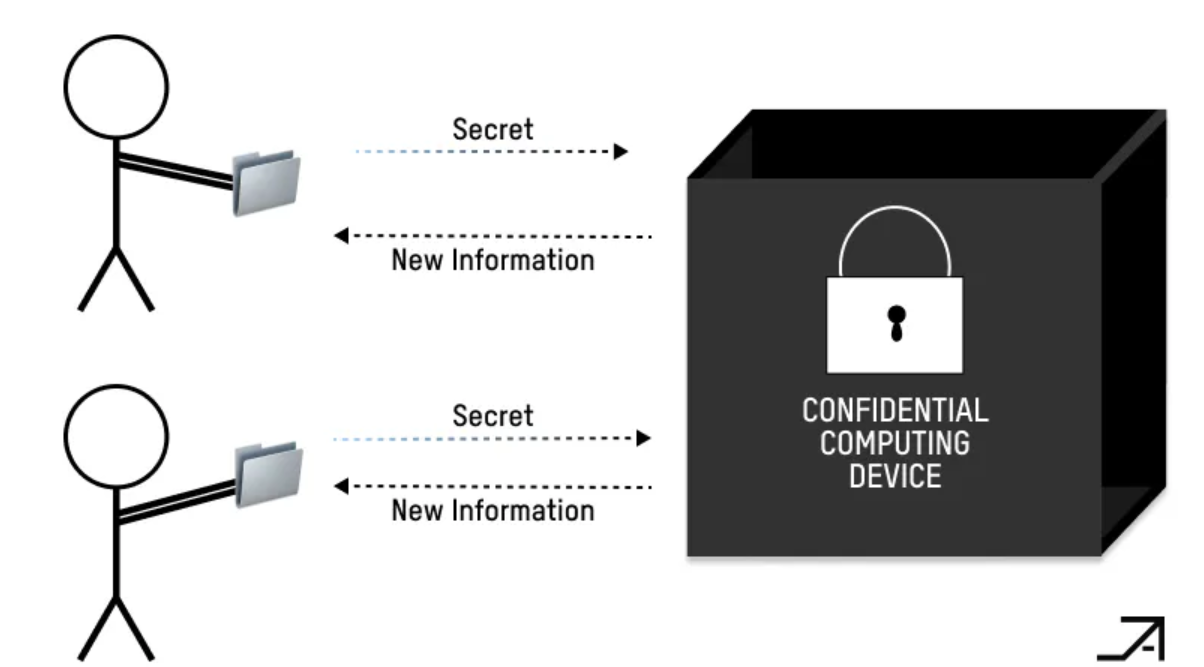

Game 2: Privacy-Preserving Computation for Information Generation

Imagine a game played by Solidity developers where players use multi-party computation (MPC) to reveal their salaries and compute averages while keeping individual salaries confidential. This would be a valuable tool for cryptographers negotiating with employers, as well as a source of entertainment.

More broadly, information games can leverage privacy-preserving technologies to expand the range of information sources—especially private data and information that can be analyzed to generate new insights. By ensuring privacy, these tools can increase the types and willingness of people to share data and compensate data providers for the value generated.

Though not exhaustive, tools used by information producers include zero-knowledge proofs (ZK), multi-party computation (MPC), fully homomorphic encryption (FHE), and trusted execution environments (TEE). While their core mechanisms differ, they ultimately converge—enabling individuals to provide sensitive information in privacy-preserving ways.

However, significant challenges remain in using software and hardware cryptographic primitives for use cases requiring strong privacy guarantees, which we’ll discuss later.

Privacy-preserving cryptography significantly broadens the design space for entirely new information games previously impossible.

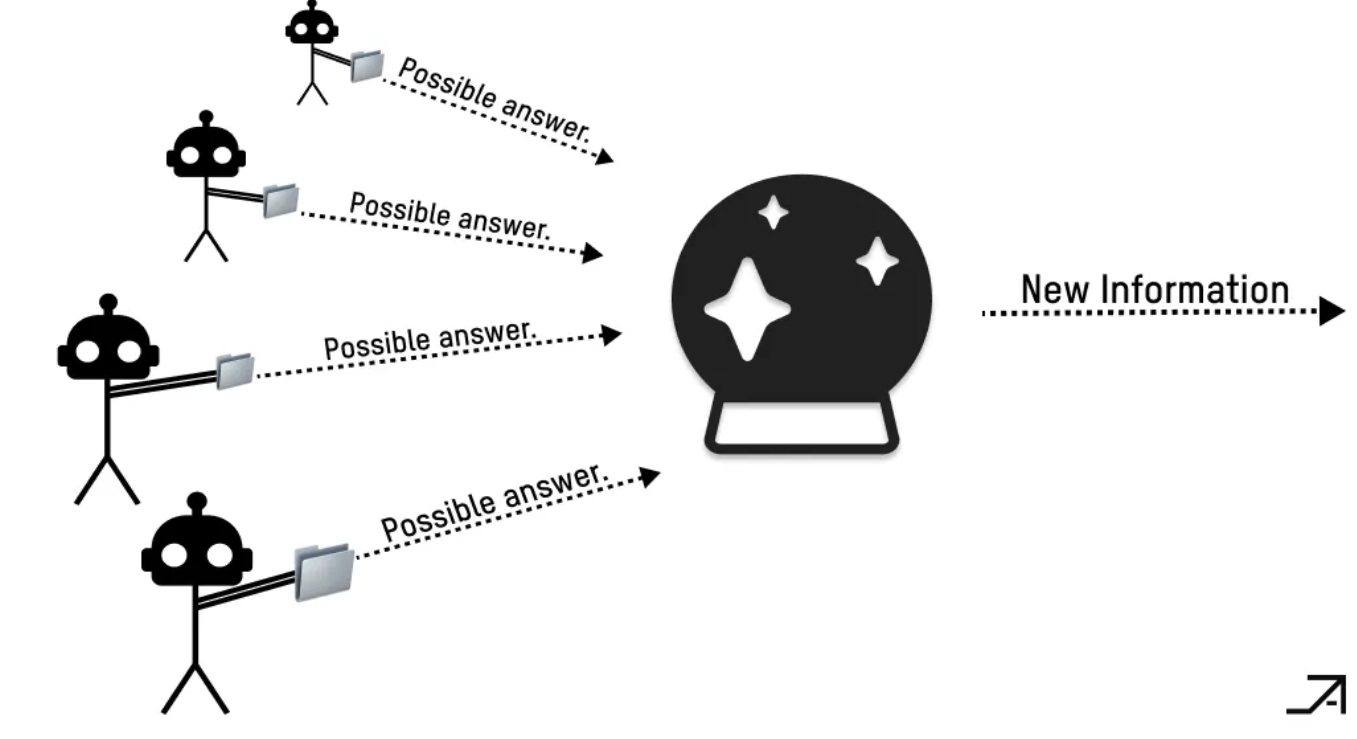

Game 3: Competition Between Models to Improve Information Production

Imagine a game where data scientists compete by developing and betting on trading models for a decentralized hedge fund. Then, the blockchain reaches consensus on scores for specific models, rewarding or penalizing participants based on prediction accuracy and impact on fund returns. This is the approach taken by Numerai, one of Ethereum’s earliest information games. Here, Ethereum’s consensus mechanism enables global competition between different models and their creators, effectively incentivizing AI to play information games and generate valuable returns.

Further, we could directly incentivize AI to play information games for us, leveraging their vast knowledge to compete in predictions. While they don’t play for fun, using intelligent machines instead of humans drastically reduces labor costs for information production. Thus, these AI models can boost liquidity in niche prediction markets where humans are typically unwilling to participate. As Vitalik noted:

“If you create a market and offer a $50 liquidity subsidy, humans won’t care much about bidding, but thousands of AIs will easily swarm in, doing their best guess. The incentive to get any single question right might be tiny, but the incentive to build an AI that makes generally good predictions could be worth millions.”

Alternatively, we could leverage consensus among machine learning models to compete around the information value they generate. Teams like Allora and Bittensor TAO are working to coordinate models and agents, broadcasting their predictions to others in the network, who then evaluate, score, and broadcast performance back. Each cycle, collective evaluations among models are used to distribute rewards or power based on prediction quality. Entrepreneurs can thus leverage continuously improving model networks to enhance the quality of information flowing through their markets.

It’s entirely possible that some information markets—where the quality of information produced by models surpasses anything achievable through human-only information games.

Monetizable Information Games

Some information games sustain themselves purely through user enjoyment. But for those wishing to monetize the value of the information they generate, more thought is required. Unfortunately, information’s inherent characteristics as a commodity lead to key market failures, hindering smooth monetization:

-

Information can only be valued after consumption, making it hard for buyers to assess whether a seller’s price accurately reflects its value.

-

Information is non-rivalrous—its consumption doesn’t reduce availability—meaning it lacks scarcity, which makes it unattractive to buyers.

-

Information’s non-excludability plus low replication cost makes it hard for sellers to prevent unauthorized access, despite high upfront production costs.

These economic traits pose challenges for both buyers and sellers trying to profit from information, potentially leading to undersupply. If information quickly becomes known to all who could benefit, buyers lose asymmetric advantages due to increased competition or collapsed plans. Fortunately, several crypto tools exist to address these issues—and are already in use.

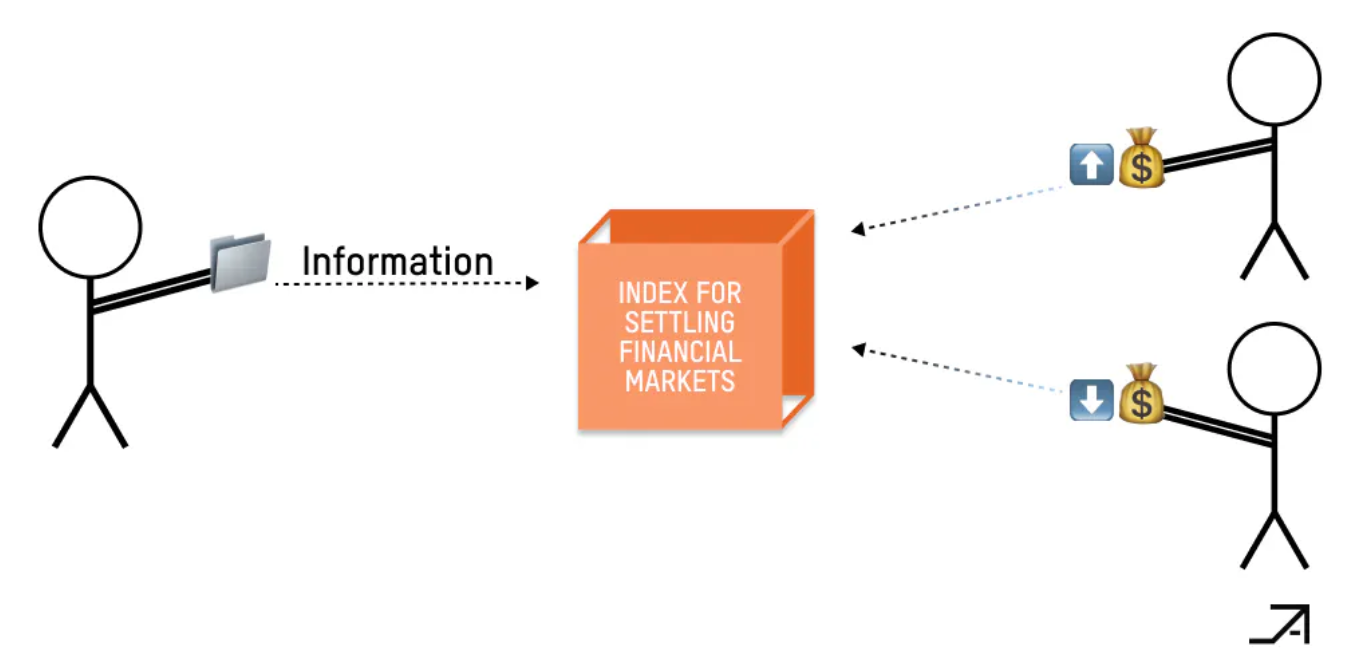

Game 4: Exchanges—Monetizing Through Information Speculation

A way to monetize information production without keeping it secret or restricting actions based on it is simply to make it public but create tools allowing people to bet on how it changes—also known as derivatives.

One company actively doing this is Parcl, whose exchange allows users to speculate on real estate market ups and downs. Parcl’s markets are powered by real-time price data gathered by Parcl Labs from a vast pool of real estate data and processed through proprietary algorithms, generating more granular and accurate information than traditional real estate indices.

While Parcl monetizes this information more directly via API, they also create an additional monetization layer by allowing traders to bet on how this information evolves over time. Other projects, like IKB and Fantasy mentioned in the “Alternative Information Markets” section of the market map, focus on monetizing through speculation or hedging against changes in existing public information—from athlete performance to creator social engagement.

If you can sell the right to speculate on your generated information, you can monetize without secrecy or restricting how buyers use it.

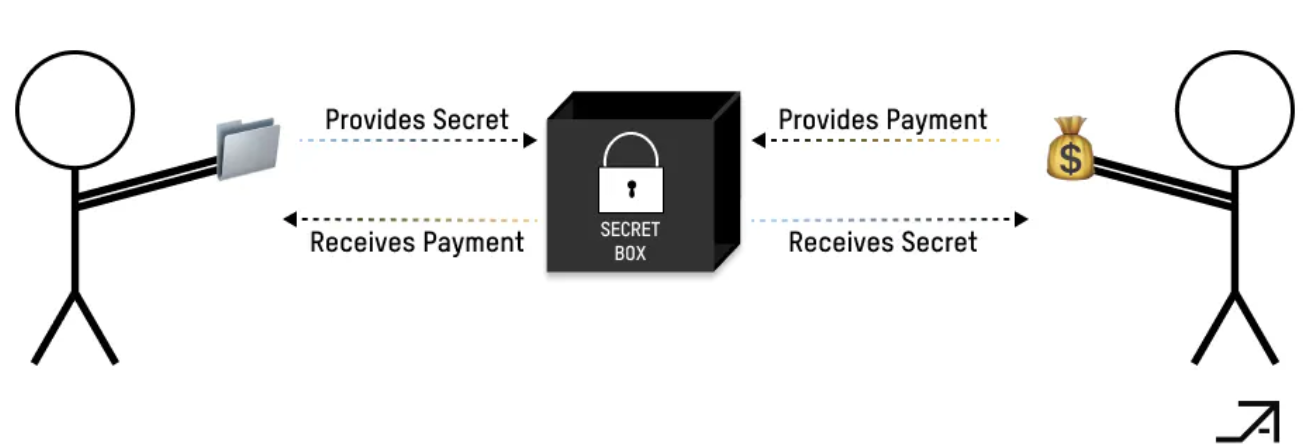

Game 5: Black Markets for Discovering Confidential Information

Imagine a game where you discover exclusive alpha about the latest on-chain activity or brand-new crypto startups before the world knows. To make this work, information must remain confidential, addressing the non-rivalry and non-excludability issues of public information. Thus, next-generation information markets are facilitating exchanges of confidential information while leveraging blockchains to discover and regulate all potential paying participants.

Freatic’s decentralized confidential information market Murmur exemplifies this approach, using NFTs and queuing systems to limit exclusive access. Information buyers first subscribe to specific topics by purchasing coupon-representing NFTs. This grants them a spot in line to redeem confidential information from publishers and optionally pay extra to slow its dissemination. Buyers can later vote on the information’s quality. Through this process, Murmur ensures information stays confidential and valuable without restricting sales to a single entity.

In contrast, Friend.tech uses keys and bonding curves to manage access to confidential information in group chats, raising entry barriers as demand increases. Thus, we can view Friend.tech keys as proxies for the average value of someone’s personal information (assuming an efficient key market). Yet players always “price in” some notion of that person’s “value” when trading keys, making it hard for buyers to assess information value. Perhaps this supports the idea thatthe most valuable “information markets” to date are actually memecoin markets—which, if you squint hard enough, are prediction markets around the symbolic value of specific trends or figures.

Setting aside memecoins, one direction for teams limiting information access is designing better bonding curves that better link access price to information value. For example, pricing for information that rapidly devalues once known could use bonding curves reflecting fast-declining value over time.

Decentralized information exchange is challenging due to trust issues and the double coincidence of wants. Blockchains have solved this for currency (Bitcoin) and will do the same for information through engaging games centered on discovering hidden information.

Game 6: “Futarchy”—Monetizing Prediction Markets

A major way to monetize information without explicit secrecy is producing and selling information that only a single organization can and will act upon. This isn’t new—many companies already monetize information by auctioning or using NDAs to restrict access to specific buyers. Yet we’re now seeing a new business model emerge on crypto rails: producing public information that’s only relevant and valuable to organizations making specific decisions.

Indeed, we’re only beginning to see prediction markets built on crypto tracks experiment with “Futarchy” (Foresight News note: coined by George Mason University professor Robin Hanson in his 2000 paper “Shall We Vote on Values, But Bet on Beliefs?”, named Word of the Year by The New York Times in 2008) as an alternative mechanism to monetize generated information.

“Futarchy” offers a novel approach to better decision-making, centered on using information generated by prediction markets. The information from prediction markets informs decisions, and when markets settle, the most accurate predictors are rewarded.

Prediction markets themselves are zero-sum for players, limiting incentives for informed traders and worsening existing liquidity bottlenecks. “Futarchy” can solve this, as wealth created by better decisions can be redistributed to traders.

Decentralized-native entities like MetaDAO are already experimenting with “Futarchy.” When a proposal is made—say, Pantera buying MetaDAO governance tokens—two prediction markets are created: “pass” supporting, “fail” opposing. Participants trade conditional tokens in these markets, speculating on the proposal’s impact on DAO value. The outcome depends on comparing the time-weighted average price (TWAP) of “pass” and “fail” tokens after a specified period. If the “pass” market’s TWAP exceeds the “fail” market’s by a set margin, the proposal passes, executing its terms and canceling “fail” market trades. This system uses market dynamics to drive governance decisions, aligning them with the market’s collective prediction of whether the proposal raises or lowers DAO value.

In some cases, “Futarchy” still requires confidentiality design. For example, if a prediction market decides hiring for a specific role, making this public creates information hazards—competitors might poach candidates based on market predictions.

Another reason for confidentiality is its impact on incentives and organizational culture. As Robin Hanson noted in his talk “The Future of Prediction Markets,” Google’s internal experiment faced resistance because executives feared public performance metrics would demotivate employees. Of course, managers aren’t inclined to implement things that might expose “the emperor’s new clothes,” a phenomenon we still see today. According to MetaDAO founder @metaproph3t, some people choose not to submit proposals because they don’t want market evaluation.

Both issues can be addressed by limiting access to prediction market information, providing it only to specific decision-makers. However, granting decision-makers autonomy to act on this information causes bettors to factor in these biases, lowering the quality of generated information.

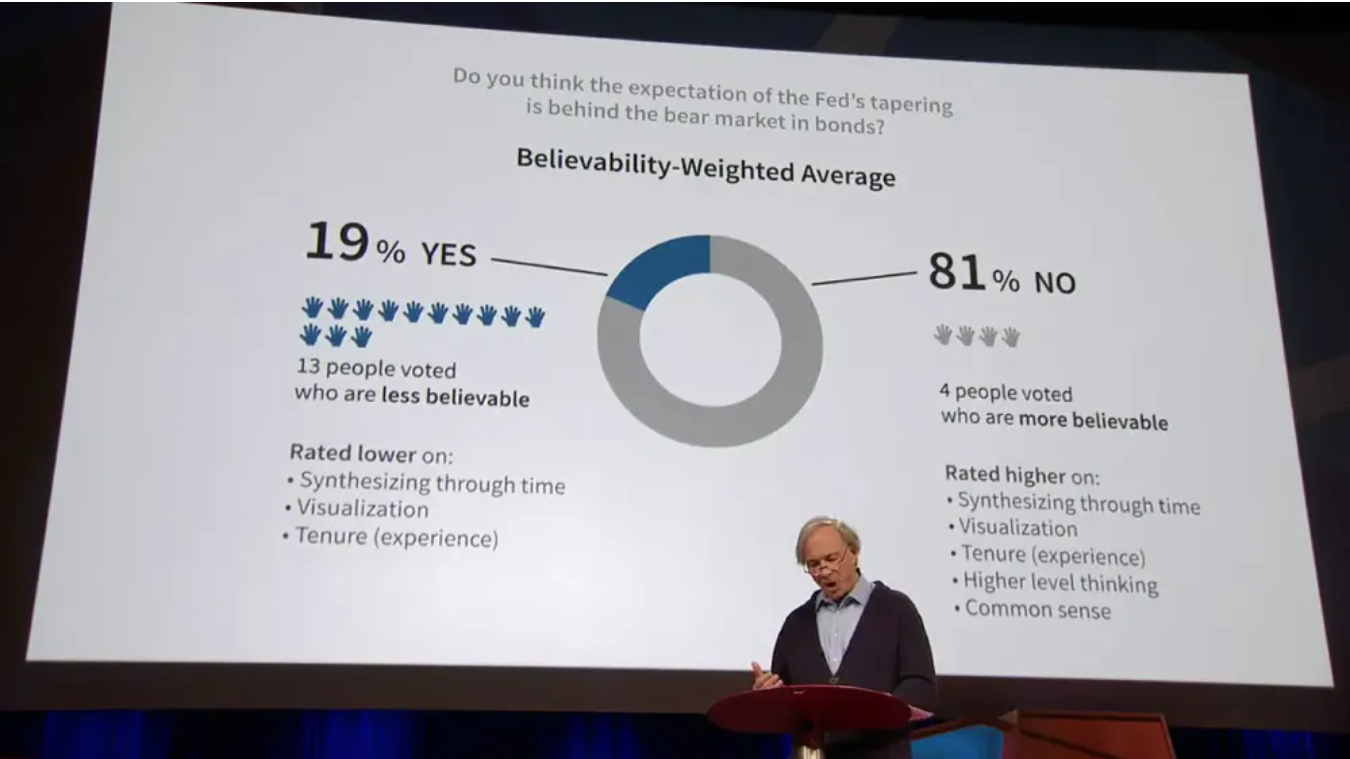

In other cases, “Futarchy” may be better suited for industries where benefits outweigh cultural impacts, such as Bridgewater’s hedge fund. Integrating blockchains could further enhance “Futarchy” credibility and prevent manipulation.

To date, prediction market monetization has been limited to speculation or hedging, but by helping organizations make better decisions, prediction markets can unlock an entirely new market—though unresolved questions remain around the role of confidential information.

Game 7: Trustworthy Commitments in Programmable Information Games

As mentioned at the start, Google monetizes information by renting usage rights to advertisers while restricting how they use it—to bidding in Google’s ad auctions. Similarly, trustworthy commitments help information sellers monetize by limiting what buyers can do with the information.

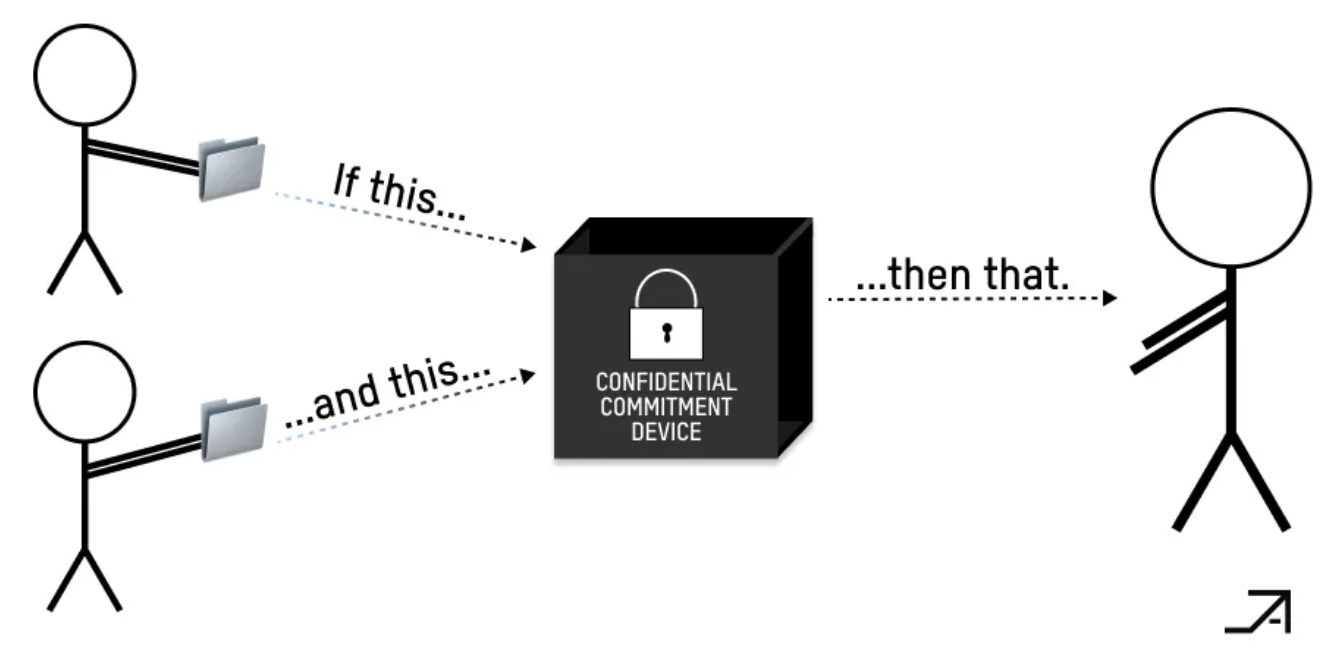

Information sellers can use cryptographic methods like MPC, TEE, and FHE to enforce trustworthy commitments on calculations buyers perform using private data. Thus, sellers can delegate their information to buyers, allowing buyers to exert specific control over future operations involving their private data without revealing the information itself.

This primitive technology unlocks various information games. Imagine traders (information sellers) selling the right to order transactions based on order history to information buyers (searchers), provided buyers commit to simulating the order history only a certain number of times. Further, imagine allowing Netflix users to delegate account usage to others, enabling them to “farm yield” from their accounts without sharing login details. Buyers unlock value from sellers’ private information, while sellers avoid the challenges of selling information directly (information being non-rivalrous, non-excludable experiential goods).

Unlocking Google-scale monetization for information game designers

TEEs currently offer a practical option for implementing such controls, though with limited confidentiality guarantees. While unsuitable for protecting large assets or sensitive data, TEEs work for use cases requiring limited access to confidential information, such as preventing frontrunning. SUAVE, a project by the Flashbots team, is building a TEE network developers can use today, with a long-term vision of enabling app developers to better harness the value of their and their users’ information.

In SUAVE’s design, blockchain integration with TEEs addresses three key TEE limitations crucial for advancing information games. First, blockchains eliminate trust in host-player communications, which could otherwise censor or act maliciously. Second, blockchains provide secure state maintenance, protecting against rollback attacks TEEs are vulnerable to. Third, blockchains are essential for enabling permissionless, censorship-resistant creation of TEE-based information games (SUAPPs), where all players can trust the smart contracts, inputs, and outputs.

While many early SUAVE-based information games will clearly focus on MEV, they have potential far beyond trading.

Game 8: Reputation and Zero-Knowledge for In-Game Markets

A key challenge in monetizing information is its intrinsic nature as an “experiential good.”The value of experiential goods is only recognizable after use, making it hard for sellers to set prices upfront. When creating mechanisms to solve this, we can also create engaging gameplay. In some games, core gameplay revolves around building reputation to distinguish oneself—like in World of Warcraft—providing both fun and a key signal for cooperation. Other games might require sellers to commit a price for intelligence (e.g., enemy locations, secret plans) without revealing the content first.

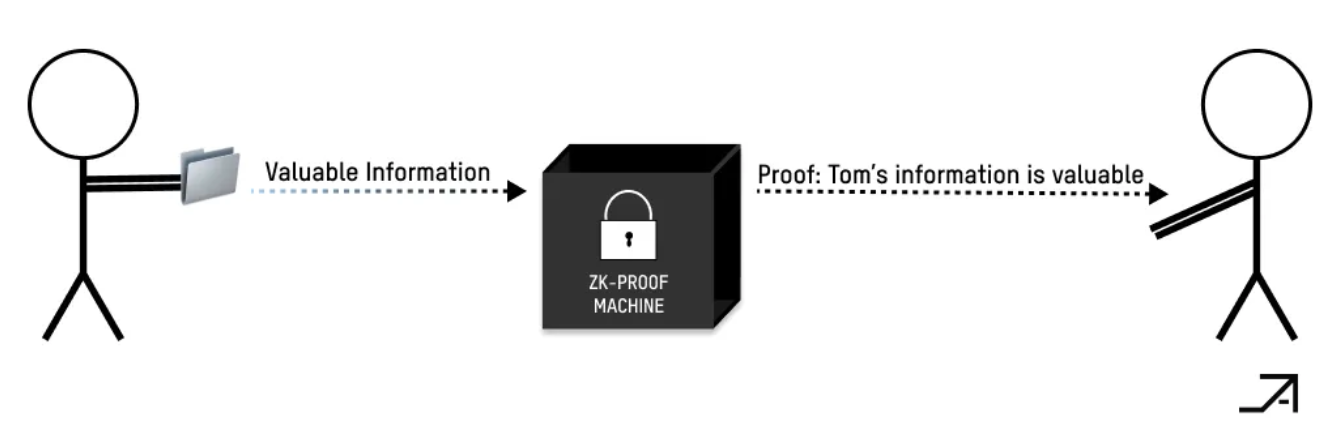

To overcome this, information game designers can leverage cryptographic solutions like zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) to verify properties of information goods (e.g., effectiveness of a trading algorithm) without disclosing actual data or code. This could involve creating cryptographic commitments, timestamping on blockchain, and providing zero-knowledge proofs of algorithm performance. However, this method only applies to information goods whose value stems from computational attributes testable on verifiable inputs.

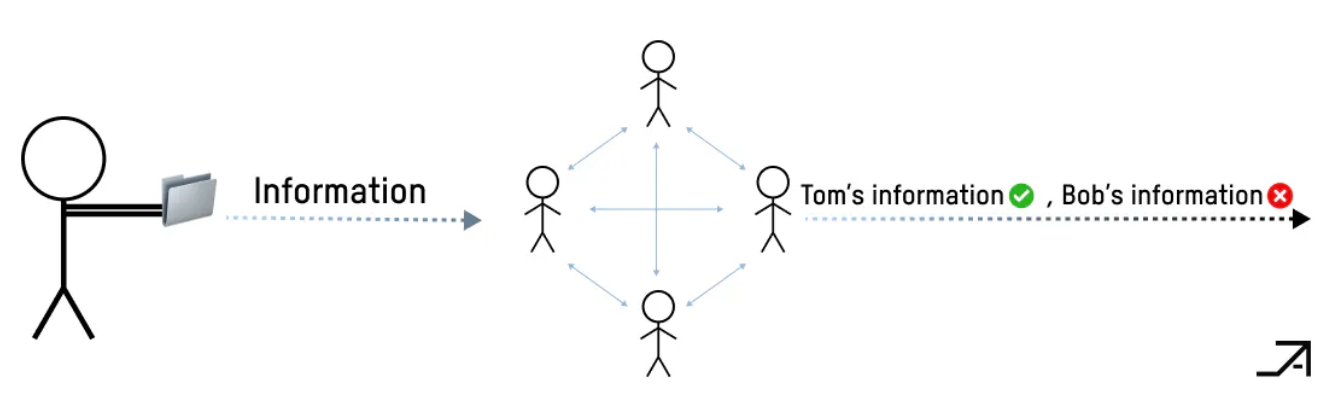

For other types of information goods, reputation and identity become crucial. Consensus mechanisms among information buyers can be used to build reputation around the value of what sellers aim to sell.

Systems like Murmur use user voting within exclusive windows to build publisher reputation, upgrading them from unverified to verified based on community feedback. This creates a transparent, immutable record of interactions, establishing trustworthy seller reputations with tight feedback loops.

Alternatively, the Erasure Bay protocol requires sellers to stake both funds and reputation as signals of information reliability. The protocol defines a “fraud factor,” allowing buyers to burn a portion of the seller’s stake if information quality is poor, ensuring sellers are incentivized to deliver high-quality information.

To avoid market failure and maximize transaction volume, game designers must equip sellers with cryptographic tools to prove their information’s value or provide trusted, fast mechanisms to build reputations from past sales.

Conclusion

Information games are nothing new. However, before programmable blockchains, game designers could only seek permission from centralized intermediaries, and players were limited to games mediated by trusted third parties.

Now, the dramatic drop in blockspace costs means anyone can create a futarchy-inspired DAO or a protocol for confidential information, integrating abundant tools for verification, arbitration, monetization, and more. Lowered barriers and open innovation on permissionless financial rails will unlock games we can’t yet imagine.

This article has shown early signs and challenges in implementing this wave of new information games, along with the potential of crypto tools to solve them. With these tools, some game designers will improve information games we already play—like trading and MEV—while others will create games that never existed before.

Yet each of these crypto-powered information games represents a small game—they need to interconnect and compose into larger wholes. The fun and thrill players get from building reputation, collaborating in teams, and vying for influence within organizations—all belong as parts of a greater whole.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News