Huang Renxun in conversation with the seven authors of the Transformer paper, discussing the future of large models

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Huang Renxun in conversation with the seven authors of the Transformer paper, discussing the future of large models

The world needs something better than Transformers, and I think everyone here would welcome its replacement by something new that can take us to a new performance plateau.

Author: Guo Xiaojing

Source: Tencent News

In 2017, a landmark paper—“Attention Is All You Need”—emerged, introducing for the first time the Transformer model based on self-attention mechanisms. This innovative architecture broke free from the constraints of traditional RNNs and CNNs, overcoming the challenge of long-range dependencies through parallelized attention mechanisms and significantly accelerating sequence data processing. The encoder-decoder structure and multi-head attention mechanism of Transformer sparked a revolution in artificial intelligence, forming the foundational architecture behind today’s popular ChatGPT.

Imagine that a Transformer model works like your brain during a conversation with a friend—able to simultaneously focus on every word spoken and understand how these words relate to one another. It grants computers human-like language comprehension. Before this, RNNs were the dominant method for language processing, but their sequential nature made them slow—like an old-fashioned tape player that must play word by word. In contrast, the Transformer acts like an efficient DJ, manipulating multiple audio tracks at once to quickly capture key information.

The emergence of the Transformer dramatically enhanced computers’ ability to process language, making tasks such as machine translation, speech recognition, and text summarization far more efficient and accurate—a giant leap forward for the entire industry.

This breakthrough was the result of collaborative efforts by eight AI scientists who previously worked at Google. Their initial goal was simple: improve Google's machine translation service. They wanted machines to fully understand and read entire sentences rather than translate words in isolation. This idea became the starting point of the “Transformer” architecture—the “self-attention” mechanism. Building on this foundation, the eight authors leveraged their individual expertise and published the paper “Attention Is All You Need” in December 2017, detailing the Transformer architecture and opening a new chapter in generative AI.

In the world of generative AI, scaling laws are the core principle. Simply put, as Transformer models grow larger, their performance improves—but this also demands more powerful computing resources to support increasingly large models and deeper networks. As a provider of high-performance computing services, NVIDIA has thus become a pivotal player in this AI wave.

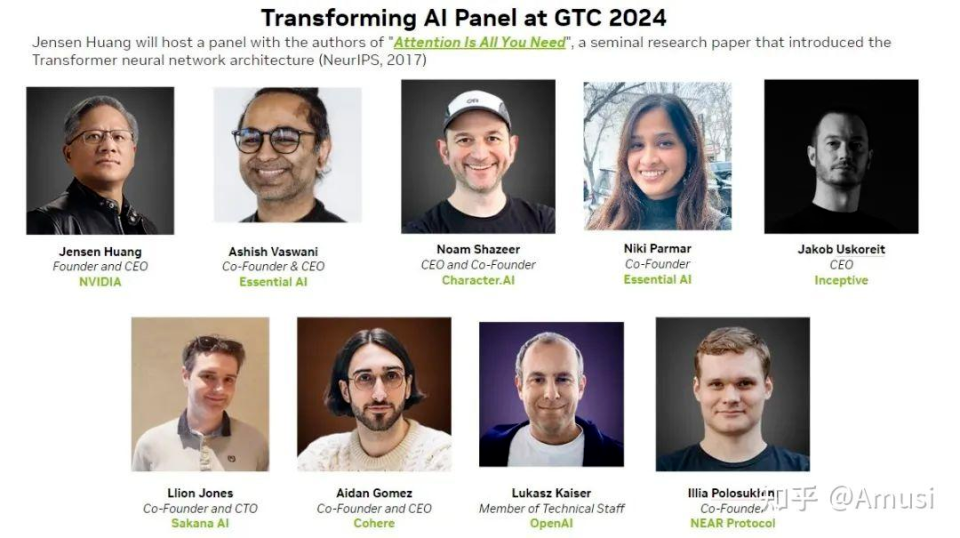

At this year’s GTC conference, NVIDIA’s Jensen Huang invited seven of the eight Transformer authors (Niki Parmar was unable to attend) to a roundtable discussion in a highly ceremonial manner—marking the first time all seven had appeared together publicly.

They shared several striking insights during the conversation:

-

The world needs something better than Transformer. I think everyone here hopes it will be replaced by something that brings us to a new performance plateau.

-

We didn’t actually succeed in our original goal. We started Transformer intending to simulate the evolution of tokens—not just linear generation, but the gradual evolution of text or code.

-

Even a simple problem like 2+2 might consume trillions of parameters in a large model. I believe adaptive computation is one of the things that must emerge next—we need to know how much computational resource to allocate for specific problems.

-

I think current models are too affordable and still too small—around $1 per million tokens, which is 100 times cheaper than buying a paperback book.

Below is the full transcript:

Jensen Huang: For the past sixty years, computer technology hasn't undergone fundamental transformation—at least not since the moment I was born. The computer systems we use today—multitasking, separation of hardware and software, software compatibility, data backup capabilities, and programming techniques used by software engineers—are largely based on the design principles of the IBM System/360—central processors, BIOS subsystems, multitasking, hardware-software separation, software system compatibility, and so on.

I believe modern computing hasn’t fundamentally changed since 1964. Though in the 1980s and 1990s, computers underwent a major transformation into the forms we recognize today. Over time, the marginal cost of computing has continuously dropped—tenfold every decade, a thousandfold every fifteen years, ten thousandfold every twenty years. In this computer revolution, the reduction in cost has been so dramatic that within two decades, computing costs have effectively decreased by ten thousand times, creating immense momentum for society.

Try to imagine if all expensive items in your life suddenly dropped to one ten-thousandth of their original price—for example, a car you bought for $200,000 twenty years ago now costing only $1. Can you envision such a change? However, the decline in computing costs did not happen overnight; it gradually reached a critical point, after which the downward trend suddenly stalled. It still improves slightly each year, but the rate of change has plateaued.

We began exploring accelerated computing, but using acceleration isn’t easy—you need to redesign everything from scratch. Previously, we might solve problems step by step, but now we need to re-engineer those steps. This is an entirely new scientific field—reformulating previous rules into parallel algorithms.

We recognized this and believed that even if we could accelerate just 1% of code and save 99% of runtime, there would certainly be applications that benefit. Our goal is to turn the impossible into possible, or make the already possible even more efficient—that’s the essence of accelerated computing.

Looking back at our company history, we realized we had the capability to accelerate various applications. Initially, we achieved remarkable speedups in gaming—so impressive that people mistakenly thought we were a gaming company. But in reality, our ambitions extended far beyond that, because this market is vast enough to drive incredible technological advancement. Such cases are rare, but we found one.

To cut a long story short, in 2012 AlexNet sparked a fire—the first collision between artificial intelligence and NVIDIA GPUs. This marked the beginning of our magical journey in this domain. A few years later, we discovered the perfect application scenario, laying the foundation for our current development.

In short, these achievements laid the groundwork for generative AI. Generative AI doesn’t just recognize images—it can convert text into images and even create entirely new content. Now, we have sufficient technical capability to understand pixels, identify them, and grasp their underlying meanings. From these meanings, we can generate new content. The ability of AI to understand the meaning behind data represents a monumental shift.

We have good reason to believe this marks the beginning of a new industrial revolution. In this revolution, we’re creating unprecedented things. For instance, in previous industrial revolutions, water served as the energy source—water flowed into our devices, generators spun, water in, electricity out—like magic.

Generative AI is a completely new kind of “software”—one that can create software itself—and relies on the collective efforts of numerous scientists. Imagine feeding raw materials—data—into a “building”—machines we call GPUs—and getting magical outputs. It’s reshaping everything. We are witnessing the birth of “AI factories.”

This transformation can be called a new industrial revolution. In the past, we’ve never truly experienced such a shift, but now it’s slowly unfolding before us. Don’t miss the next decade, because in these ten years, we’ll unlock tremendous productivity. The clock has started ticking, and our researchers have already begun moving.

Today, we’ve invited the creators of Transformer to discuss where generative AI will take us in the future.

They are:

Ashish Vaswani: Joined Google Brain in 2016. In April 2022, co-founded Adept AI with Niki Parmar. Left the company in December 2022 and co-founded another AI startup, Essential AI.

Niki Parmar: Worked at Google Brain for four years. Co-founded Adept AI and Essential AI with Ashish Vaswani.

Jakob Uszkoreit: Worked at Google from 2008 to 2021. Left Google in 2021 and co-founded Inceptive, a company focused on AI-driven life sciences, aiming to design next-generation RNA molecules using neural networks and high-throughput experiments.

Illia Polosukhin: Joined Google in 2014. One of the earliest to leave the team, co-founded blockchain company NEAR Protocol in 2017.

Noam Shazeer: Worked at Google between 2000–2009 and 2012–2021. In 2021, left Google and co-founded Character.AI with former Google engineer Daniel De Freitas.

Llion Jones: Previously worked at Delcam and YouTube. Joined Google in 2012 as a software engineer. Later left Google to found AI startup sakana.ai.

Lukasz Kaiser: Former researcher at the French National Centre for Scientific Research. Joined Google in 2013. Left Google in 2021 to become a researcher at OpenAI.

Aidan Gomez: Graduated from the University of Toronto. Was an intern at Google Brain when the Transformer paper was published. The second member of the team to leave Google. Co-founded Cohere in 2019.

Jensen Huang: Sit comfortably, please jump in anytime—there’s no topic off-limits here. You can even jump off your chairs to debate. Let’s start with the basics: what problem were you trying to solve, and what inspired you to build Transformer?

Illia Polosukhin: If you want to deploy models that can truly read search results—processing piles of documents—you need models that can rapidly handle such information. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) at the time couldn’t meet that demand.

Indeed, while RNNs and early attention mechanisms (Arnens) attracted attention, they still required reading word by word, which was inefficient.

Jakob Uszkoreit: We were generating training data faster than we could train state-of-the-art architectures. In fact, we used simpler architectures, like feedforward networks with n-grams as input features. These architectures, due to faster training speeds, often outperformed more complex, advanced models—even at Google-scale datasets.

Powerful RNNs, especially Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, already existed at the time.

Noam Shazeer: It seemed like a pressing issue. Around 2015, we began noticing scaling laws—you could see intelligence increasing as model size grew. It was almost the best problem in history—so simple: just predict the next token, and it becomes smart enough to do a million different things. You just scale up and make it better.

The huge frustration was how cumbersome RNNs were to work with. Then I overheard these guys discussing replacing them with convolutions or attention. I thought, great, let’s do it. I like to compare Transformer to the leap from steam engines to internal combustion engines. We could’ve done the Industrial Revolution with steam, but it would’ve been painful. Internal combustion made everything better.

Ashish Vaswani: During my graduate studies, I learned some bitter lessons, especially while working on machine translation. I realized: I won’t learn complex linguistic rules. Gradient descent—the method we use to train models—is a better teacher than I am. So instead of learning rules myself, I let gradient descent do all the work. That was my second lesson.

What I learned from these hard lessons is that scalable, general-purpose architectures ultimately win in the long run. Today it might be tokens; tomorrow it could be actions on computers—they’ll start mimicking our activities and automating much of what we do. As we discussed, Transformer, especially its self-attention mechanism, has broad applicability. It also makes gradient descent work better. And physics—because one thing I learned from Noam is that matrix multiplication is a good idea.

Noam Shazeer: This pattern keeps repeating. Every time you add a bunch of rules, gradient descent eventually learns them better than you ever could. That’s exactly it. Just like deep learning—we’re building AI models shaped like GPUs. Now we’re building models shaped like supercomputers. Yes, supercomputers are now the model. Yes, really. Supercomputers exist solely so we can shape models into supercomputers.

Jensen Huang: So what problem were you solving?

Lukasz Kaiser: Machine translation. Five years ago, the process seemed extremely difficult—you’d collect data, maybe do translations, but results were barely acceptable. The level was quite basic. But now, these models can learn translation even without data. You just provide one language and another, and the model learns translation on its own—an emergent ability that works impressively well.

Llion Jones: But the intuition behind “Attention” was what we needed. So I came up with the title—basically, what happened was during our search for a name.

We were doing ablation studies—removing parts of the model just to see if performance worsened. Surprisingly, it started improving. Removing convolutions altogether worked much better. That’s where the title came from.

Ashish Vaswani: What’s interesting is we started from a basic framework, added components—including convolutions—and later removed them. Multi-head attention and many other crucial elements followed.

Jensen Huang: Who came up with the name "Transformer"? Why "Transformer"?

Jakob Uszkoreit: We liked the name. It was somewhat random, but felt creative—changing our data production mode using this logic. All machine learning is transformer—disruptors.

Noam Shazeer: We hadn’t thought of this name earlier. It feels particularly simple, and many people love it. I considered names like Yaakov, but settled on “Transformer”—it describes the model’s principle: transforming signals. By this logic, nearly all machine learning gets transformed.

Llion Jones: Transformer became widely known not just for translation content, but because we wanted a broader description of this transformation. I don’t think we did anything extraordinary, but as a disruptor, as an engine, it makes sense. People can grasp this large language model, engine, and logic—architecturally, it was an early starting point.

But we did realize we were trying to create something extremely general—something that could transform anything into anything else. And I don’t think we anticipated how well Transformer would perform on images—that was surprising. It may seem logical to you, but the idea of splitting images into patches and tokenizing each point—this architectural concept existed early.

So when we built tensor-to-tensor libraries, our real focus was scaling up autoregressive training. Not just language, but also image and audio components.

So Lukasz said he was doing translation. I think he undersold himself—all these ideas are now converging, integrated into models.

Actually, it was all there early—these ideas were permeating, just took time. Lukasz’s vision was training across all academic datasets—image to text, text to image, audio to text, text to text. We should train on everything.

That idea drove scaling efforts and ultimately succeeded. It’s fascinating—we can translate images to text, text to images, text to text.

You’re using it in biology or bio-software—similar to computer software. It starts as a program, then compiles into something runnable on GPUs.

A bio-software life begins with a specification of behavior. Say you want to print a protein, like a specific one in cells. Then you learn via deep learning how to convert that into an RNA molecule—which, once inside your cell, expresses that behavior. So the idea goes far beyond translating into English.

Jensen Huang: Did you set up a large lab to produce all this?

Aidan Gomez: Abundant availability—still open, as data is usually publicly funded. But you still need clear data about the phenomena you're modeling.

Modeling specific products—like protein expression or mRNA vaccines—yes, in Palo Alto we have robots and people in lab coats, including learning researchers and former biologists.

Now we see ourselves as pioneers—actually creating this data and validating models for molecular design. But the original idea was translation.

Jensen Huang: The original idea was machine translation. I want to ask—what were the key milestones in architectural strengthening and breakthroughs, and how did they influence Transformer’s design?

Aidan Gomez: Along the way, did you see significant additional contributions atop the base Transformer design? I think a lot of work has gone into accelerating inference, making models more efficient.

I’m still unsettled because our original form remains so similar. I think the world needs something better than Transformer. I believe everyone here hopes it will be replaced by something that brings us to a new performance plateau.

Let me ask everyone here: what do you think comes next? Because this step is exciting, yet feels too similar to what we had six or seven years ago, right?

Llion Jones: Yes, people are surprised by how similar it still is. People often ask me what’s next because I’m a paper author. Like magic, you wave a wand—what appears next? I want to emphasize how this principle was designed. We don’t just need improvement—we need dramatically better performance.

Because if it’s only slightly better, that’s not enough to push the entire AI industry toward something new. So we’re stuck on the original model—even if technically it may not be the most powerful thing we have now.

But everyone knows what personal tools they want—you want better context windows, faster token generation. Well, I’m not sure you’ll like this answer, but they currently waste too much compute. We’re striving for efficiency—thank you.

Jensen Huang: I think we’re making it more effective—thank you!

Jakob Uszkoreit: But I think it’s mainly about resource allocation, not total consumption. We shouldn’t spend too much on easy problems or too little on hard ones and end up with no solution.

Illia Polosukhin: Take 2+2—if properly input into the model, it uses a trillion parameters. So I believe adaptive computation must emerge—we need to know how much compute to spend on specific problems.

Aidan Gomez: We know current computer generation capacity—this is where focus should go. I believe this is a universe-level game-changer and the future direction.

Lukasz Kaiser: This concept existed before Transformer and was integrated into it. Actually, I’m not sure if everyone here realizes—we didn’t succeed in our original goal. We started wanting to simulate token evolution—not just linear generation, but gradual evolution of text or code. We iterate, edit—making it possible to mimic not only how humans develop text but include them in the process. Because if you can naturally generate content like humans, they can actually provide feedback, right?

We’ve all studied Shannon’s papers. Our initial idea was focusing solely on language modeling and perplexity—but that didn’t pan out. I think this is where we can further advance. It also relates to how we intelligently organize compute resources now—this applies to image processing too. Diffusion models, for example, have an interesting property: they can iteratively refine and enhance quality. We don’t have that capability yet.

The fundamental question: what knowledge should be embedded in the model, and what should stay outside? Should we use retrieval models? RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) is one example. Similarly, regarding reasoning—should certain reasoning tasks be handled externally via symbolic systems, or directly within the model? Much of this is about efficiency. I do believe large models will eventually learn to compute 2+2, but calculating it via number accumulation is clearly inefficient.

Jensen Huang: If AI only needs to calculate 2+2, it should directly use a calculator—using minimal energy—because we know calculators are the most efficient tool for 2+2. But if someone asks AI: How did you decide 2+2? Do you know 2+2 is correct? That could consume massive resources.

Noam Shazeer: Exactly. You mentioned an example earlier, but I’m equally confident that the AI systems developed here are intelligent enough to actively use calculators.

Currently, global public products (GPP) already do this. I think current models are too cheap and still too small. They’re affordable thanks to technologies like NV—thanks for delivering them.

Computation cost per operation is roughly $10^{-18}. Or around that order. Thank you for producing so much compute. But observing a model with 500 billion parameters performing a trillion operations per token—about $1 per million tokens—this is 100 times cheaper than buying and reading a paperback. Our applications are worth millions or more times the cost of efficient computation on giant neural networks. I mean, they’re undoubtedly more valuable than curing cancer—and beyond.

Ashish Vaswani: I think making the world smarter means obtaining feedback from the world—can we achieve multi-task, multi-threaded parallelism? If you truly want to build such a model, helping design it is a great approach.

Jensen Huang: Could you briefly share why you founded your companies?

Ashish Vaswani: At our company, our goal is building models and tackling new tasks. Our job is understanding task goals and content, evolving with changing needs. Since 2021, I realized the biggest issue with models isn’t just making them smarter—we also need the right talent to interpret them. We want the world and models to intertwine, making models larger and greater. Progress requires real-world engagement—impossible in a lab vacuum.

Noam Shazeer: In 2021, we co-founded this company. We had exceptional technology, but it wasn’t benefiting many. Imagine being a patient hearing this—I think billions need help with different tasks. That’s the essence of deep learning—advancing through comparison. Thanks to Jensen’s push, our ultimate goal is helping people worldwide. You must test—we now need faster solutions so hundreds can apply these apps. Initially, not everyone used them—many just for fun—but they worked, they functioned.

Jakob Uszkoreit: Thank you. I’d like to discuss our ecological software ecosystem. In 2021, I co-founded this company to tackle scientifically impactful problems. Previously, our work was quite complex. But when I had my first child, my worldview shifted. We want to make human life easier and contribute to protein research. Especially as a father, I hope to transform healthcare and ensure science positively impacts human survival and development. Protein structures and breakdowns are already affected, but we lack data. We must act based on data—it’s both duty and paternal responsibility.

Jensen Huang: I love your perspective. I’m always fascinated by new drug design—enabling computers to learn drug discovery and generation. If models can learn and design drugs, and labs test them, we can validate feasibility.

Llion Jones: Yes, I’m the last speaker. Our co-founded company is Sakana AI—meaning “fish” in Japanese. We named it after fish because schools of fish inspire our search for intelligence. Combining many tested elements creates complex, beautiful outcomes. Many may not grasp details, but our core philosophy internally is “learning always wins.”

Whether solving problems or learning anything, learning ensures victory. In generative AI, learning content helps us win. As researchers here, I want to remind everyone—we give AI models true meaning, enabling them to help us understand the universe’s mysteries. Actually, I’d like to announce exciting progress—we’re thrilled. While we have research milestones, we’re undergoing transformative development. Current model management is organized, involving real participation. We’re making models more viable—using large models and transformative patterns to change how people perceive the world and universe. That’s our goal.

Aidan Gomez: My motivation aligns with Noam Shazeer’s. I believe computing is entering a new paradigm, changing existing products and our work methods. Everything is computer-based, with internal technological shifts. What’s our role? I bridge gaps. We see enterprises building platforms, adapting and integrating products—direct user-facing. This is how we advance tech—making it more economical and accessible.

Jensen Huang: I particularly appreciate how calm Noam Shazeer is while you’re so excited. Your personalities contrast beautifully. Now, please, Lukasz Kaiser.

Lukasz Kaiser: My experience at OpenAI was deeply disruptive. The company was fun—we processed massive data—but ultimately, my role remained a data processor.

Illia Polosukhin: I was the first to leave. I firmly believe we’ll achieve major progress—software will change the world. The most direct path is teaching machines to write code, making programming accessible to everyone.

At NEAR, progress has been limited, but we’re committed to integrating human wisdom, gathering relevant data—further inspiring people to recognize the need for foundational methodologies. This pattern represents foundational progress. These large models are widely used globally, applied in aerospace and other fields, facilitating cross-domain communication. They provide us capabilities. With deeper usage, we see more models emerging—currently few copyright disputes.

We’re now in a new generative era—an age celebrating innovation and innovators. We want to actively embrace change and seek different methods to build a cool model.

Jensen Huang: This positive feedback system benefits our overall economy. We can now design economies better. Someone asks: in this era where GPT models train on databases of billions of tokens, what’s next? What new model technologies will emerge? What do you want to explore? Where do your data sources come from?

Illia Polosukhin: Our starting point is vectors and displacements. We need models with real economic value—people can evaluate them, apply your tech and tools practically, making the whole model better.

Jensen Huang: How do you conduct domain-specific training? What was the initial interaction pattern? Was it model-to-model communication? Or generative models and techniques?

Illia Polosukhin: In our team, everyone has their technical specialty.

Jakob Uszkoreit: Next is reasoning. We all recognize reasoning’s importance, but much work is still manually done by engineers. We’re teaching them interactive Q&A-style responses—we want them to understand why, together providing strong reasoning frameworks. We want models to generate desired content—this generative approach is what we pursue. Whether video, text, or 3D information, they should be integrated.

Lukasz Kaiser: Do people realize reasoning actually stems from data? When we begin reasoning, given a dataset, we ask: why is this data unique? Then we discover various applications—all rooted in data-driven reasoning. Due to computing power and systems, we can evolve from there. We can reason about related content, run experiments.

Often, it originates from data. I believe reasoning advances rapidly—data models matter greatly. Soon there’ll be more interactive content. We haven’t trained sufficiently—this isn’t the key element. We need richer data.

Noam Shazeer: Designing data—for example, designing teaching machines—could involve hundreds of millions of different tokens.

Ashish Vaswani: One point I’d add: in this field, we have many partners achieving milestone progress. What’s the best automation algorithm? Actually breaking real-world tasks into components. Our models are crucial—they help acquire data, check if data is correctly positioned. On one hand, they help us focus on data; on the other, such data provides high-quality models for abstract tasks. Thus, measuring this progress is also a form of creativity, a way of scientific development, and a path toward automated advancement.

Jensen Huang: Without solid measurement, you can’t achieve excellent engineering. Do any of you have questions for each other?

Illia Polosukhin: Nobody really wants to trace their exact steps. But actually, we want to understand and explore what we’re doing—gather enough data and information, conduct sound reasoning. For example, if you have six steps, but five-step reasoning lets you skip one. Sometimes you don’t need six steps; sometimes you need more—how do you reproduce such scenarios? What’s needed to evolve beyond tokens?

Lukasz Kaiser: Personally, I believe reproducing such large models is extremely complex. Systems keep advancing, but essentially you need to design a method. Humans are good at reproduction—in human history, we constantly reproduce successful scenarios.

Jensen Huang: Pleasure talking with you all. I hope you get chances to interact and create indescribable magic. Thank you all for joining—deeply grateful!

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News