Vitalik's Latest Speech: Traditional Electoral Systems Are Prone to Vote Suppression, Quadratic Voting Can Improve Democracy

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik's Latest Speech: Traditional Electoral Systems Are Prone to Vote Suppression, Quadratic Voting Can Improve Democracy

Vitalik believes that in all voting systems, apart from mechanism design, community participation is extremely crucial.

Written by BlockTempo

Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin participated on January 19 in the Tempo X Accelerator Plurality Forum – "Building Islands from Sand: How Taiwan's Experience with Pluralistic Democracy Can Advance into the Web3 Era?" hosted by BlockTempo in Taipei. During the forum, he explored theories and practical applications of various voting systems—from traditional voting to quadratic voting—explaining how these systems function in different contexts and influence democratic decision-making processes.

*This report is generated from the content of a public YouTube video, using AI tools such as ChatGPT and based on this transcript. The copyright is under CC0. If there are translation issues, we welcome anyone to collaborate via the online document and provide feedback.

The Importance of Voting Mechanisms Across Fields

Before diving into specific voting systems, Vitalik first discussed the diversity of voting systems and their applications across various domains. He noted that people often associate voting with national or municipal elections, but voting processes occur at all scales and contexts. Beyond government elections, examples include opinion polls and internal voting within nonprofit organizations. He emphasized that although opinion polls are theoretically non-binding, their outcomes significantly influence discourse and culture.

Vitalik then turned to "micro-democracies" on social media platforms. Using tweets as an example, he explained how user interactions like likes and retweets on platforms such as X (formerly Twitter), Farcaster, and Mastodon shape public perception of content. These interactions, he argued, are effectively "millions of daily referendums" determining which viewpoints deserve broader attention.

Limitations and Drawbacks of Traditional Voting Systems

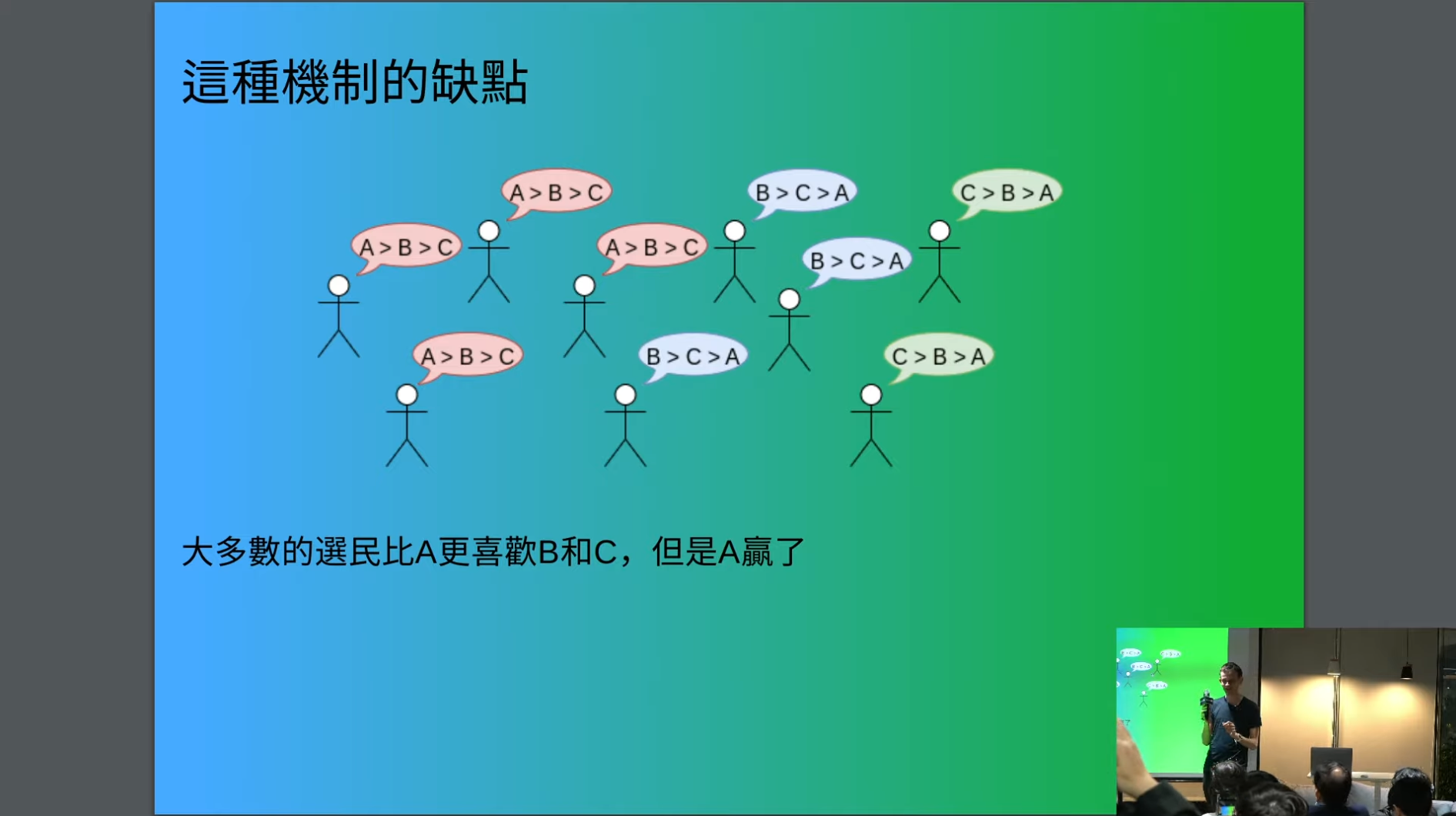

Addressing the limitations of current traditional voting systems, Vitalik posed a fundamental question: Why isn't simply voting for A or B sufficient? He illustrated this with a simple example involving nine voters supporting three candidates: A receives four votes, B receives three, and C receives two. In this case, while A appears to win, A may not actually be the most broadly preferred candidate.

Vitalik explaining drawbacks of traditional voting

Vitalik further analyzed voter preferences, clarifying that even if A wins the vote, it doesn’t mean A is the top choice for most voters. He pointed out that if a large group strongly opposes A but their votes are split between B and C, A might incorrectly emerge as the winner due to vote fragmentation.

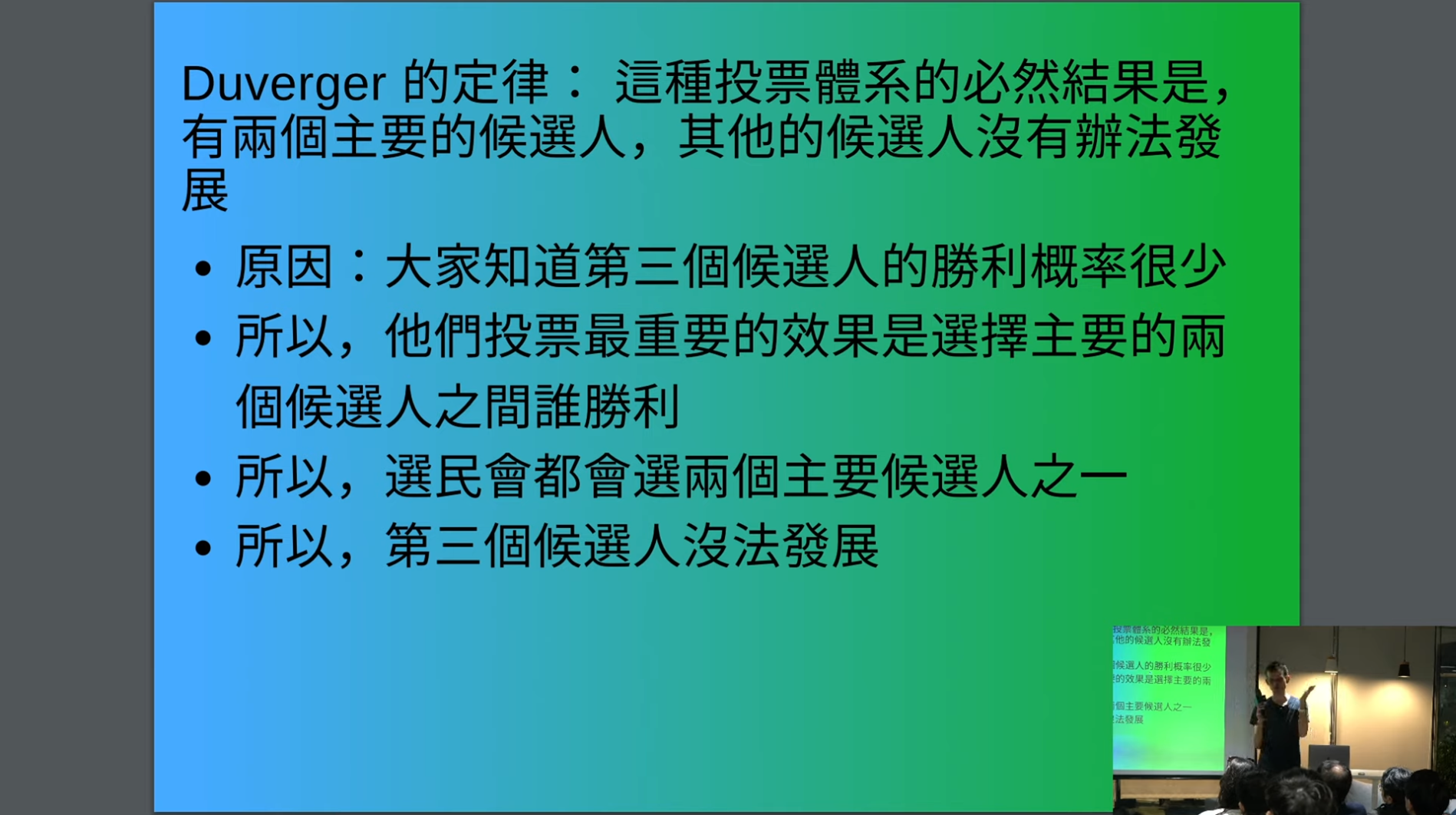

To clarify further, Vitalik referenced "Duverger’s Law," explaining why such simple voting systems often lead to a two-party dominance. He cited the United States as a clear example where the electoral system frequently devolves into competition between just two major parties.

Duverger’s Law and the Abandonment-Preservation Effect

From the perspective of Duverger’s Law, Vitalik explained why smaller parties struggle to succeed under current political systems. He noted that voters generally perceive small-party candidates as having little chance of winning, especially since they’ve never won before. As a result, even if voters strongly prefer a small-party candidate, they may instead vote for a major-party candidate perceived as more likely to win.

He highlighted that this mindset leads voters to choose only between the two main candidates, reinforcing the dominance of the two major parties and making it difficult for others to enter the democratic process—a phenomenon known as the “abandonment-preservation effect.”

In summary, under Duverger’s Law and the abandonment-preservation effect, even when neither of the two major party candidates is ideal, voters still tend to support the one they see as “less bad.” This dynamic makes it extremely difficult to sustain elections with more than two competitive candidates.

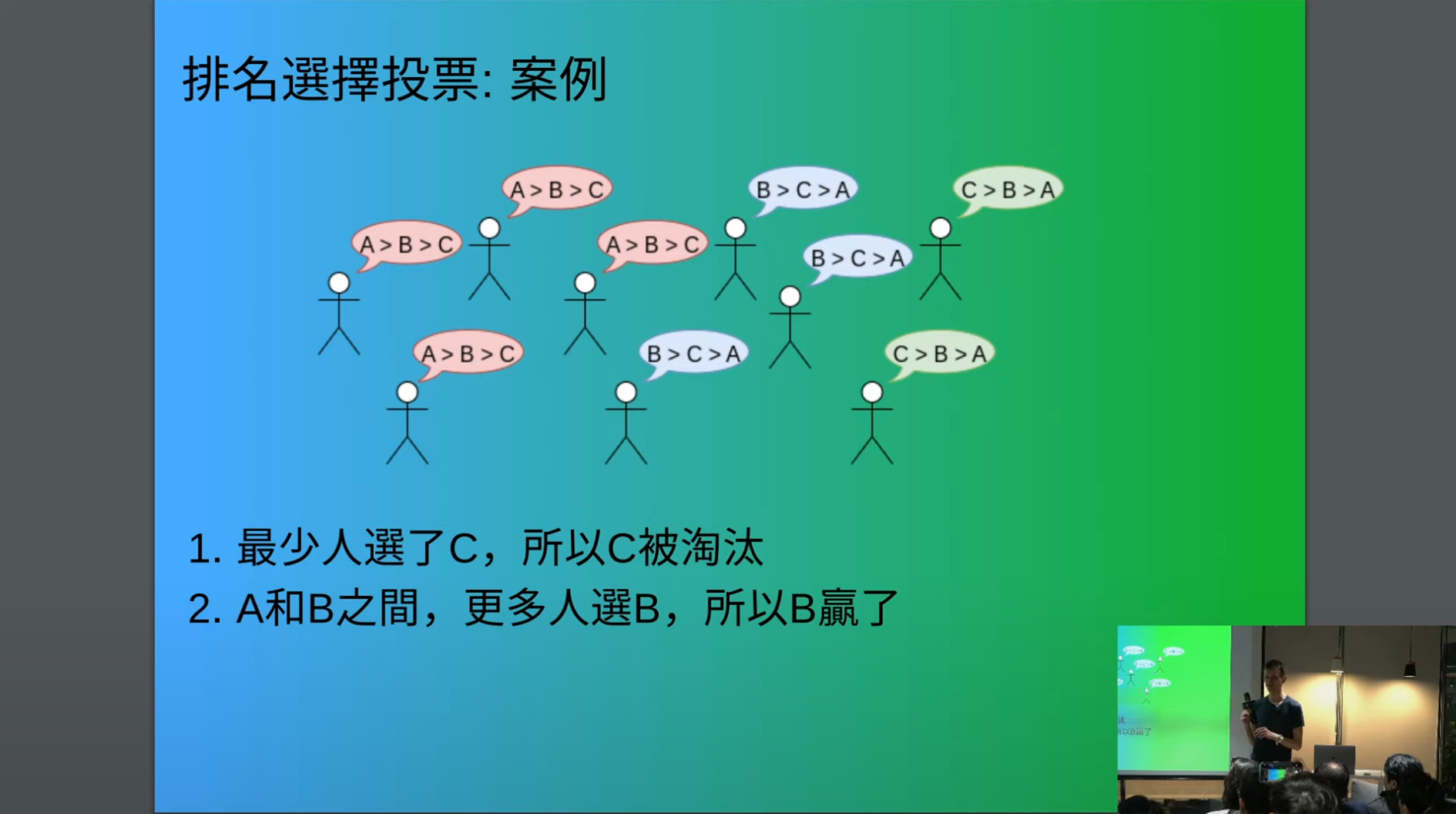

Advantages and Disadvantages of Ranked Choice Voting

Regarding ranked choice voting (RCV), Vitalik explained that RCV allows each voter to rank candidates in order of preference, from most to least favored. The counting process involves multiple rounds of elimination, where the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated in each round until only one remains.

Vitalik used an example to show how this method can resolve certain issues in traditional voting. In a race among candidates A, B, and C, RCV can better reflect true voter preferences and allow the candidate with broadest support to win. However, he also acknowledged its drawback: complexity, which can sometimes produce counterintuitive results.

Example illustrating ranked choice voting

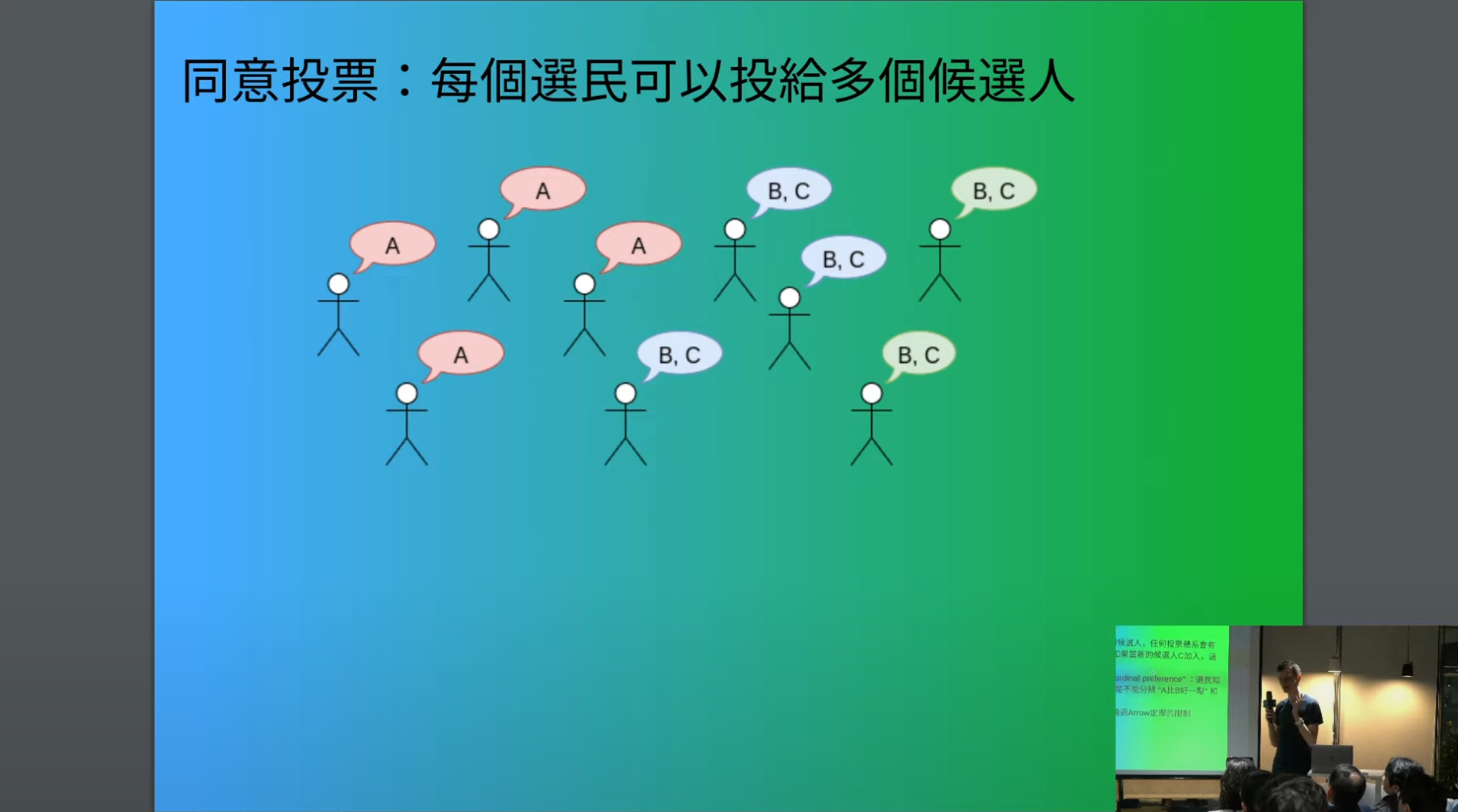

Approval Voting: A Simpler Alternative

Next, Vitalik introduced another voting method: approval voting. In approval voting, voters can approve any number of candidates—one, two, three, or even none.

To illustrate how it works, Vitalik gave an example: suppose four voters favor candidate A, while five others strongly dislike A but have differing preferences between B and C. The four supporters of A would approve A, while the five opponents would approve both B and C. This results in B and C each receiving five approvals, tying for victory.

Vitalik noted that in real-world scenarios with larger voter pools, slight differences in vote counts would likely break the tie, leading to a single winner. He emphasized that approval voting produces meaningful outcomes and is far simpler than ranked choice voting and other complex systems.

Vitalik explaining approval voting

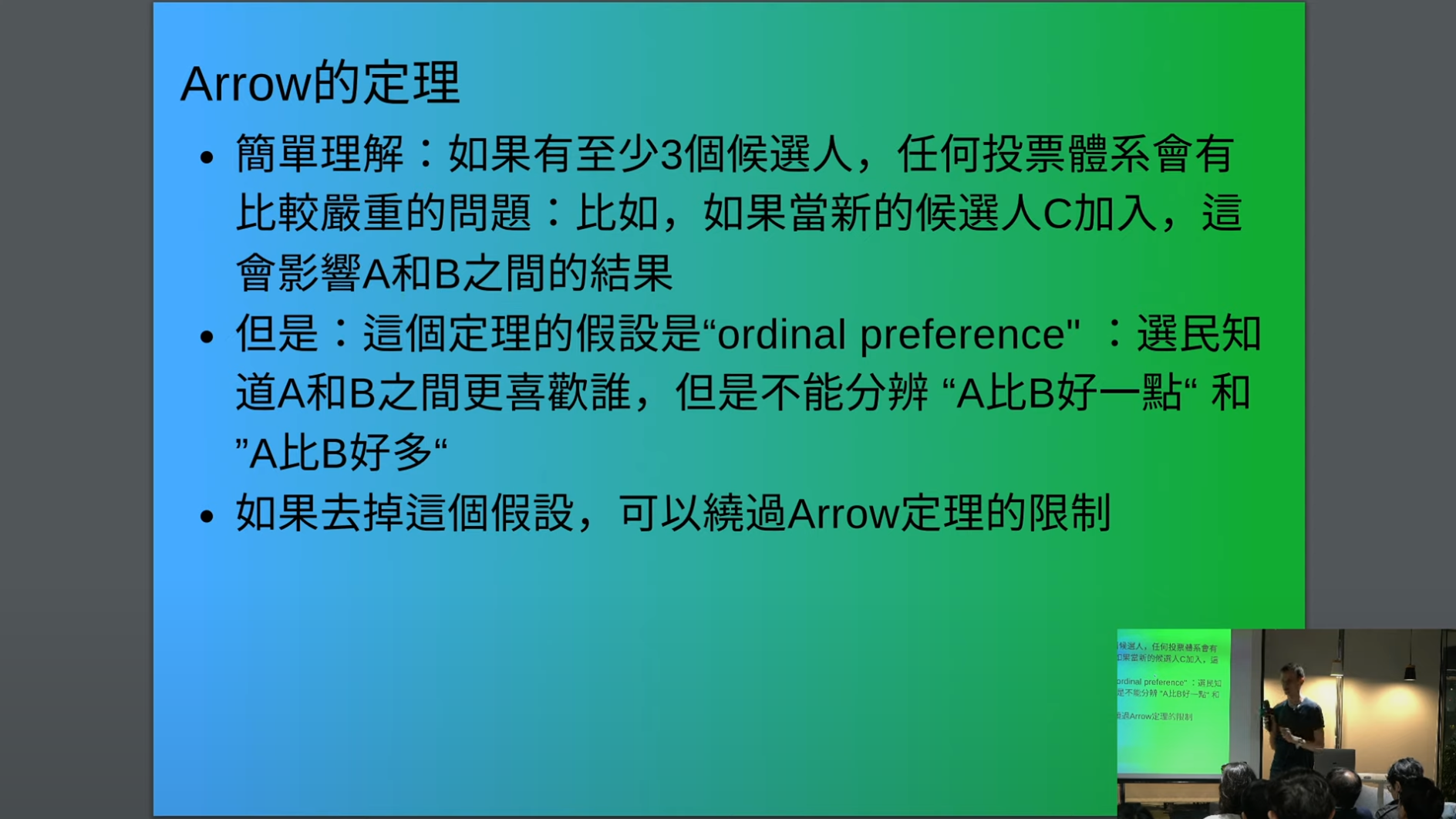

The Dilemma Posed by Arrow’s Theorem

Following this, Vitalik discussed Arrow’s Theorem and its implications for voting systems. He summarized Arrow’s Theorem simply: in any election with at least three candidates, every voting mechanism may yield clearly incorrect results under certain conditions. This typically occurs due to violations of the “independence of irrelevant alternatives” principle—meaning that introducing a new candidate C could change the outcome between A and B, which intuitively seems unfair.

Vitalik then explained that Arrow’s Theorem assumes ordinal preferences—that is, voting systems can capture whether you prefer A over B, but not *how much* you prefer A over B. He noted that once voting systems begin accounting for intensity of preference, the dilemmas posed by Arrow’s Theorem can be mitigated.

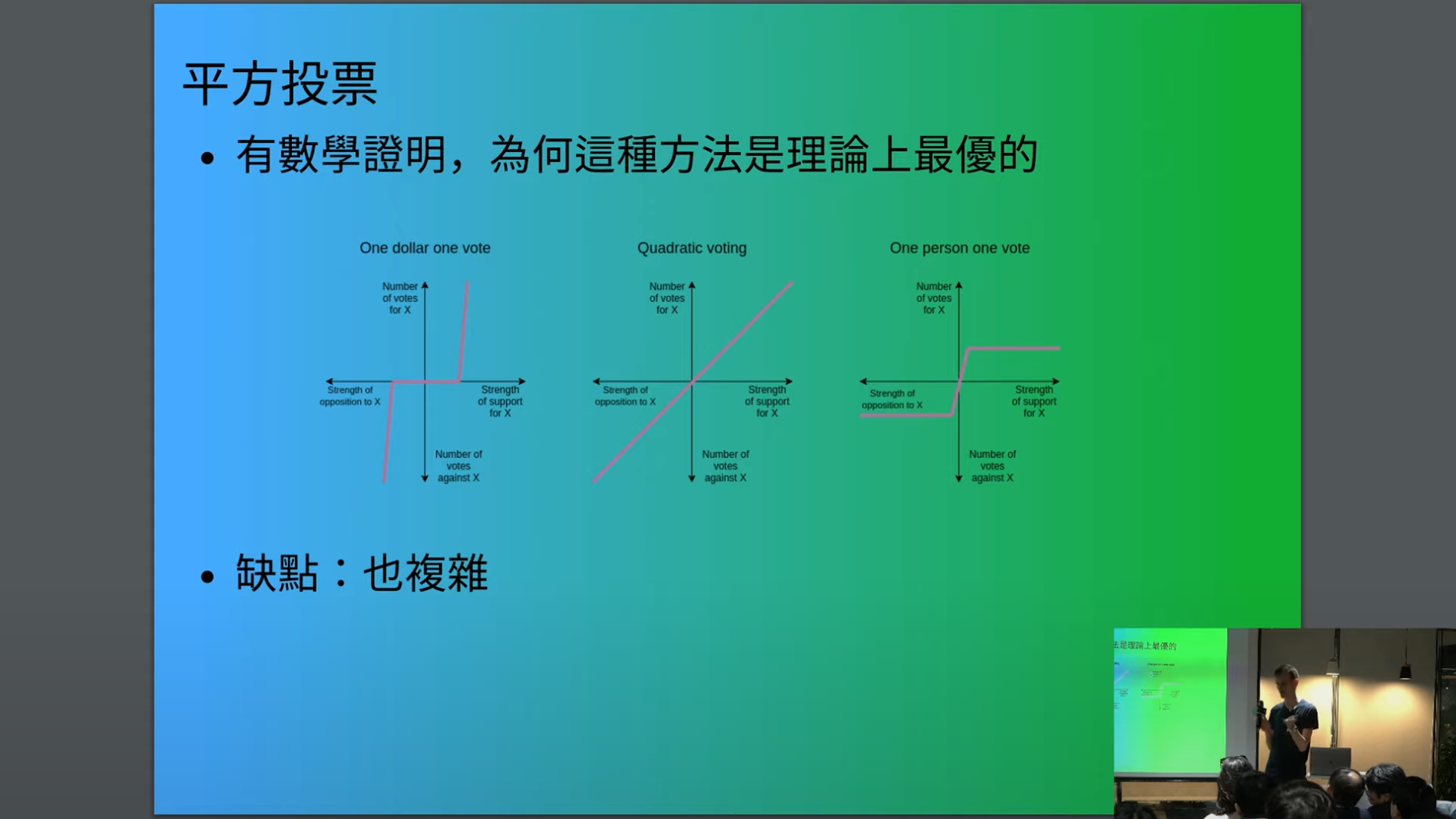

In practice, Vitalik said, allowing systems to consider the degree of preference enables better outcomes. He cited approval voting as one effective method because it implicitly recognizes preference intensity. He then introduced quadratic voting—a more sophisticated system that allows voters to allocate their preferences using a fixed budget of voting power.

Considering the challenges faced by existing voting mechanisms, Vitalik explained the mathematical logic behind quadratic voting: the cost of each vote increases quadratically with the number of votes cast. This feature encourages participants to use their votes more thoughtfully and prevents manipulation through mass low-value voting. It helps reduce extreme voting behaviors, resulting in outcomes that are more representative and fair.

Vitalik mentioned real-world applications of quadratic voting, such as Gitcoin Grants’ quadratic funding pools and various DAO implementations. He believes this mechanism can extend beyond cryptocurrency into diverse communities and decision-making contexts.

Finally, Vitalik stressed the importance of practical experimentation and encouraged communities to actively participate in testing and improving different voting mechanisms. He believes such efforts will deepen understanding of how voting systems work and help refine their design, ultimately enabling fairer and more representative decision-making.

Conclusion & Q&A

As the forum concluded, Ethereum founder Vitalik particularly emphasized the value of quadratic voting. However, he also stressed that beyond mechanism design, community participation is crucial. He encouraged ongoing experimentation and refinement to achieve fairer and more representative decision-making.

Vitalik believes voting mechanisms have broad applicability, which is precisely why people care about democracy and politics—and why those involved in cryptocurrency and Web3 often find themselves in the same room as political activists. Both groups care deeply about similar issues and face common challenges.

During the session, numerous attendees at Tempo X actively raised questions for Vitalik regarding democratic voting mechanisms.

Jimmy’s Question

Q: In different communities and crypto ecosystems implementing voting systems, is there one you think performs relatively well? And if so, is there a framework we can use to evaluate these different governance and voting systems?

A: For instance, the Optimism Collective’s Public Goods Funding program uses a unique approach where people submit ideal funding amounts, and the median is selected. This differs from previously discussed voting mechanisms, yet I believe there’s some level of mapping possible between them.

Additionally, I observe that each decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) has its own distinct yes/no voting process for proposals, reflecting the wide diversity of voting mechanisms. I’d also caution against overemphasizing the voting mechanism itself. While important, the surrounding “communication structure” matters even more—I’d estimate it accounts for about 75% of the decision-making process, while the voting mechanism itself only about 25%.

Regarding Optimism’s voting, for example, I support delegation systems because they allow individuals to pre-commit to how they’ll vote. Representatives can publish voting manifests, and others can choose to follow them. This structure enhances the quality of the mechanism rather than merely sitting atop it.

In many DAOs, when voting on mechanisms is required, members don’t just vote—they also engage in governance forums. These spaces are equally important to me, as they provide pathways for understanding and participation. Although these communication structures are difficult to model mathematically, they play a critical role in governance.

Chih-Chieh Hung’s Question

Q: I’m curious about cheating mechanisms in quadratic voting (QV), especially methods to prevent or detect such behavior. I understand that under QV, obtaining 100 votes costs 10,000 points.

However, I’m concerned that if someone finds a way to get the same number of votes for only 1,000 points, this would drastically undercut the intended cost of 10,000 points for 100 votes. Such cheating would not only be unfair to the system but potentially harmful to all participants, especially if others remain unaware. How can we detect and prevent such behavior within this system?

A: To address collusion in quadratic voting, we can technically make cheating harder—for example, using approaches like those in MACI (Minimal Anti-Collusion Infrastructure). However, the challenge lies in potential misuse of publicly disclosed individual voting data, as seen in Gitcoin Grants, where such information has been exploited for retroactive airdrops, undermining the mechanism.

We also face challenges in protecting personal identity security, and technical solutions may not be perfect. Therefore, we must also improve incentive structures through mechanism design. For example, giving greater voting weight to individuals who disagree on other issues can limit the influence of colluding actors controlling multiple accounts. I believe combining both strategies is valuable.

Ching-Fang Chen’s Question (Partner at Ming Fu International Law Firm)

Q: Yes, I have a question about new voting methods requiring constitutional amendments, which in turn require legislative approval. Yet legislatures are typically elected using old methods. Existing institutions are unlikely to adopt a voting system that undermines their own interests. So, is there any way to break this cycle?

A: Yes, I think this really depends on context. For example, in the U.S. electoral context I focus on, we see how the system collapses into a two-party dominance. We can discuss whether those parties would allow a third party to exist—or whether they wouldn’t.

Even on this issue, I think incentives may be more open than people assume. Even within the Republican and Democratic parties, they aren’t monolithic entities but complex coalitions of diverse interests—including individuals who might genuinely want to see a viable third party emerge.

So, I believe incentives in any system are highly complex. I agree this entrenchment is a key reason for political stagnation. But sometimes, the world is more complicated than it appears—even in positive ways. And sometimes, change does happen, you know.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News