Zee Prime Capital: From Small Markets to Big Success – How Can Crypto Projects Find Their Market Entry Point?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Zee Prime Capital: From Small Markets to Big Success – How Can Crypto Projects Find Their Market Entry Point?

Success requires progress, and progress is achieved in sequence—major discoveries come after minor ones.

Written by: Rapolas

Translated by: TechFlow

For founders, nothing creates a greater barrier than presenting a slide claiming infinite TAM (Total Addressable Market) potential. Anyone who says their TAM is "everyone on the internet" or "every smartphone user" reveals they haven’t deeply understood their target market.

Every market consists of finer sub-markets; if you’re a startup, chances are you can explain the specific niche your product serves at inception. That’s why we say building a product for everyone means it resonates with no one.

Every successful product at launch must either be a novel idea or a uniquely executed take on an already tested concept; therefore, most users will inevitably ignore it at first.

Capturing 1% of a trillion-dollar market (even though currently not feasible) already presents an attractive $10 billion vision—but without a unique value proposition within a sub-segment of that large market, it sounds like trying to board a flight already in the air. You need to find a smaller plane (or a jetpack)—your own wedge.

The Blockchain Wedge

What we know today as cryptocurrency or blockchain in the mainstream began with Bitcoin’s whitepaper. It was a protest against the existing banking and monetary system. Its proposed peer-to-peer payment system, free from centralized intermediaries, was an elegant solution to a very specific problem.

Bitcoin validated its original purpose as a payment mechanism, but the underlying blockchain technology later inspired a broader range of applications. If the original Bitcoin whitepaper had also proposed launching finance, social networks, gaming, and art on the blockchain, it would have achieved nothing. The mere idea of blockchain would have raised skepticism; applying blockchain to solve every imaginable problem sets the bar too high.

If you observe the blockchain applications that have grown and survived until now, you’ll notice they started by solving a very narrow problem (or one that didn’t even seem like a problem), which mattered deeply to a small group of users. Few people can clearly identify a problem they face while simultaneously offering a concrete solution (if they could, these problems would have been solved long ago).

Of course, the mystery lies in how a problem important only to a few evolves into one relevant to the majority. In some cases, great products define the problem for consumers. You couldn’t imagine driving around in a car until you saw one (then your problem became how to get one), just as you couldn’t imagine perfectly using a full touchscreen phone before owning one.

This is why building startups (and investing in them) has no standard formula and is often inspired by science fiction. Founders’ intuition guides them to navigate and bet on a particular outcome; when this intuition is lacking, people resort to solving abstract problems for large groups with little in common.

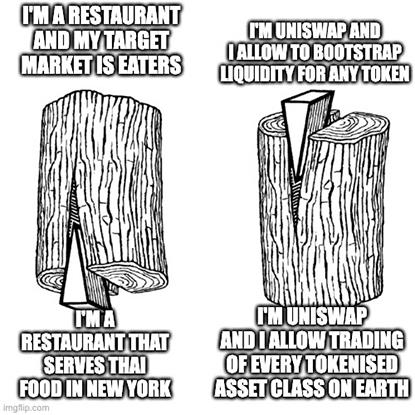

Uniswap processes nearly $10 billion in daily trading volume and is genuinely seen as a competitor to centralized exchanges. Yet, it is technically an inferior product for trading—if its pitch were simply “trade, but on-chain,” it wouldn’t have succeeded.

Uniswap V1’s wedge was enabling permissionless liquidity bootstrapping (and trading) for the long tail of tokens—something market makers and centralized exchanges couldn’t offer but was essential for project founders. Even today, the term “bootstrapping liquidity” is primarily associated with Uniswap, much like “Google” is synonymous with search.

By solving this “narrow” problem and establishing on-chain usage patterns, Uniswap captured adjacent markets (like ETH trading) that would typically occur on centralized exchanges, reinforcing success by minimizing AMM shortcomings (e.g., through concentrated liquidity).

The key isn’t building a perfect product for everyone. It’s about solving someone’s problem (or defining one, as previously discussed), then leveraging that momentum to expand into adjacent areas while iterating the product. We’ve now reached a point where Uniswap’s 2023 trading volume exceeds Coinbase’s.

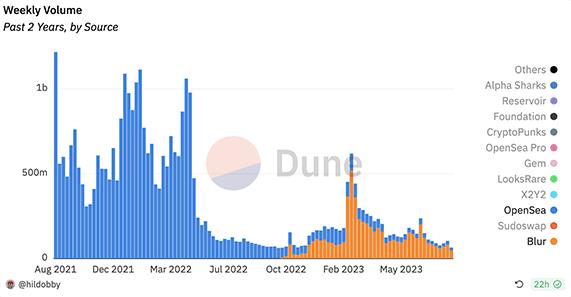

Although the Blur vs. OpenSea comparison may not be trending today, we believe Blur excelled in identifying two aspects that enabled it to carve out space in a market dominated by OpenSea:

-

The NFT investor market isn’t uniform. There’s a clear distinction between collectors (passive holders accepting illiquidity and fees) and traders (active participants seeking higher liquidity and lower fees). OpenSea served the former at the expense of the latter—there’s an inherent conflict between the two.

-

OpenSea failed to utilize tokens, whereas tokens themselves are more crypto-native than anything else.

If OpenSea’s target users were artists and collectors, trading volume might not be the perfect or sole metric of market success; conversely, if Blur’s users are traders, trading volume becomes critical because it depends on available liquidity. This is exactly what Blur achieved by rewarding market-making (providing bid/ask prices) with tokens.

Despite criticism claiming Blur mainly serves a few advanced users, if these “whales” are trendsetters, that’s not a bad thing. In fact, building for a small, passionate group allows a) rapid validation and release of product ideas; b) superior marketing outcomes.

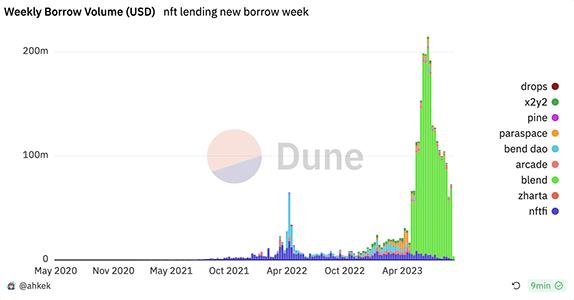

With Blur already possessing the deepest market liquidity, it could launch an adjacent yet highly relevant product—Blur Lend, or Blend—a lending market using NFTs as collateral.

Discovering Big Markets from Small Ones

The examples above illustrate how successful companies create their own monopolies. They bypassed competition through their wedges. Uniswap doesn’t compete head-on with Binance; Blur doesn’t fight OpenSea for the same users; blockchain doesn’t compete with the “internet” or traditional financial institutions—blockchain is its own entity with unique attributes.

To elaborate further, borrowing Blake Masters’ interpretation of Thielism:

“The conventional view is that capitalism and perfect competition are synonymous. No one is a monopolist. Competition exists among firms, and profits are eroded by competition. But this is a strange narrative. A better way to see it is treating capitalism and perfect competition as opposites; capitalism is about capital accumulation, while in a world of perfect competition, you can’t make money.”

Paradoxically, under perfect competition, companies start broad but immediately narrow their market to pursue differentiation (even if narrowing doesn’t feel like what they’re doing). But if they avoid perfect competition and begin in their own (small) market, they can only grow—not shrink.

“Therefore, the best business models are those where you can tell a compelling story about the future. These stories vary, but follow the same pattern: find a small target market, become the best in the world at serving it, take over adjacent markets, expand your scope, and capture more and more.”

When observing large markets, people tend to focus on the mid-to-late stages, when momentum itself drives growth and success is obvious. But success is only obvious in hindsight—people fail to appreciate the secret insights required to start a small product or service that could lead to a multi-hundred-billion-dollar market.

Consider how Newton laid the foundation for classical mechanics. This branch of physics, dealing with motion and forces acting on objects, underpins all engineering disciplines. But becoming an outstanding engineer requires more than understanding classical mechanics—it demands secret knowledge within traditional, well-known mechanical domains.

That’s why every founder who successfully avoids competition understands competition—but doesn’t need excessive knowledge, because that’s not their advantage. Businesses understand competition much like engineers intuitively grasp Newton’s laws of motion.

Intuitively, we believe every major brand today started with a narrow wedge:

-

Facebook began as a platform exclusively for Harvard students, later expanding to other universities, high schools, and the general public;

-

LinkedIn’s go-to-market strategy relied heavily on tech industry employees, allowing it to overcome cold-start challenges (its growth wasn’t dependent on tech trends);

-

Nvidia initially served the gaming industry, later expanding into model training in data centers, and built the CUDA software computing platform to support it;

-

Google’s key insight was the PageRank algorithm, which delivered superior search result quality compared to other engines. This not only led to the most profitable advertising business but also Google Cloud, hardware, and more;

-

Porsche started as a sports car company but now primarily sells SUVs. Production of sporty 911 and Boxster models hasn’t grown much since the late 1990s.

All these companies eventually expanded into adjacent markets—domains that seemed unreachable on day one (advertising, hardware, cloud, etc.). But no company exemplifies the power of the wedge strategy better than Amazon.

Among all sellable product categories, Amazon chose books—a perfect category for building an online retailer, offering over 3 million titles versus physical stores limited to under 100,000. In other words, it was ideal for demonstrating how retail shopping would shift from brick-and-mortar to online. Amazon sourced inventory from several book distributors to fulfill orders.

Existing customer traffic was used to launch other product categories and introduce third-party seller listings, further expanding supply. This evolved into the Amazon Marketplace we know today—but originated from a single category (books) and a less scalable transaction model (direct mail).

The volume Amazon handled required building internal logistics operations—distribution and fulfillment centers—which eventually matured into a preferred shipping provider offering logistics-as-a-service to third-party companies beyond Amazon Marketplace. Amazon’s shipping created a value proposition for retail consumers that, in most cases, surpassed traditional carriers like UPS and DHL. While many logistics startups hoped to disrupt legacy shippers, most failed because they never shipped any real volume. Amazon brought its own.

As Amazon’s e-commerce business grew in scale and complexity, internal teams needed a set of public infrastructure services and hardened APIs accessible to all. Amazon’s rapid growth pushed engineering teams to strengthen their infrastructure.

Multiple teams at Amazon seemed to be working on the AWS concept simultaneously. Ben Black, co-author of the idea behind Elastic Compute Cloud (AWS’s first product), wrote:

“Chris always pushed me to change the infrastructure, especially driving better abstraction and unification, crucial for effective scaling. He wanted one unified IP network instead of Amazon’s then-messy VLAN setup, so we designed it, built it, and worked with developers to adapt their applications.”

“Chris and I wrote a short paper describing a fully standardized, fully automated vision for Amazon’s infrastructure, heavily relying on web services for storage, etc. Near the end, we mentioned the possibility of selling virtual servers as a service.”

Originally starting as an internal project, it ultimately led to AWS’s launch and an entirely new market—the cloud. By 2022, annual cloud spending reached half a trillion dollars. But when AWS launched in 2006, Amazon employees didn’t fully appreciate the potential of the idea—it was their own market, full of unknowns, thus not worth quantifying.

Wedges, Economics, and Volatility

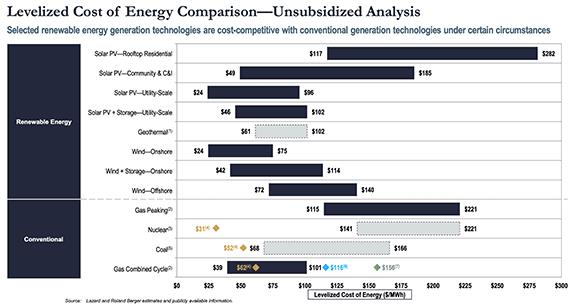

Although renewable energy and investments in renewables have been popular since the 2000s, their wedge has always relied on government subsidies via tax credits. Supporters of climate action argue the wedge is environmental, but try making that case to people struggling to pay energy bills. For a long time, renewables weren’t economically viable on their own (even with subsidies):

Consequently, during the early cycle, returns on capital invested were extremely poor (especially in solar, which historically delivered worse economic returns per dollar than wind). Most renewable developers and suppliers from that era went bankrupt or performed poorly in public markets.

There was no secret behind 2000s-era renewables—wind and solar power had been understood and utilized for thousands of years (vertical-axis windmills, solar concentration). The industry progressed under government initiatives and budgets encouraging private-sector development of solar panels and wind turbines until, in certain cases, unsubsidized renewables became competitive.

Our point is that cheap and idle blockchains resemble non-economic, subsidized renewables. Just as renewables lacked clear advantages beyond subsidies and hoped costs would eventually drop, most current blockchain infrastructure research and development rely on the same premise—abundant venture capital and predictions of declining transaction costs. But what if consumer demand externally accelerates development?

Blockchain transaction costs have been low enough for long enough to allow product wedges to emerge (and they’ve done so multiple times before). If you’re a founder betting your crypto product will gain adoption once Rollup transaction costs drop from $0.10 to $0.01, you’re likely heading in the wrong direction. Applications on Solana and NEAR already serve hundreds of thousands or millions of users.

Crypto has two directions: resisting censorship and enabling private money/payments (already successful but hard to scale); and creating global wealth online through technology. In the latter, crypto has a massive wedge—it offers volatility and easily accessible liquidity for every new asset (unlike the real world).

In crypto, we’ve already seen ICOs, NFTs, ERC-20 tokens, LBPs, and recently friend.tech. So don’t hate the player, hate the game. These aren’t destinations—they’re means to an end.

Volatility buys founders time and user attention. In many ways, it functions as a customer acquisition tool. The best crypto founders leverage this momentum to test and launch killer products while managing pressure and inflated expectations. However, your native token’s volatility shouldn’t be the default assumption—other speculative mechanisms exist that won’t undermine long-term product-market fit discovery.

Conclusion

There’s no standard method for discovering and executing great ideas. We don’t know for sure whether secrets are created or discovered, whether your product should solve someone’s problem or “create” one for them, or whether first-mover or second-mover advantage matters more.

But one thing is clear—success requires progress, and progress happens sequentially (though sometimes unexpectedly), with major discoveries preceded by smaller ones. Wedges are crucial for finding product-market fit—not casting a wide net, but testing product ideas with engaged users.

Through numerous examples (both Web2 and crypto), we’ve shown that the success stories aspiring founders admire all began with small, obscure ideas. Founders can’t predict dependency paths at the outset; they can’t foresee all adjacent markets right on the horizon. It’s the “adjacent possible” that enables companies to identify and absorb new markets as they move forward.

We hope to see crypto founders adopt “wedge” as their default buzzword going forward (just as they embraced “super app” this year).

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News