From the Internet to Blockchain: Tracing the Evolution of Trust and Verification

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

From the Internet to Blockchain: Tracing the Evolution of Trust and Verification

What happens when the forms of identity we use for blockchain applications can evolve?

Written by: JOEL JOHN, SIDDHARTH

Translated by: TechFlow

Do you remember July 1993? I wasn’t born yet. Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Twitter didn’t exist either. Much like blockchain today, the internet was then a slowly emerging phenomenon. The applications needed to attract and retain users were missing. Internet subscriptions were expensive, imposing significant costs on users—$5 per hour to use the internet. The technology was in its infancy and easy to dismiss.

The above comic was published at that time, drawn by an artist with no technical background. Reportedly, he had an expensive internet subscription about to expire. That was his entire context for understanding the internet. Yet it perfectly captured the state of the technology then: mechanisms for verifying identity and reducing bad behavior did not exist.

Most emerging networks follow such a common trend. It's hard to determine who participated early on. One of Jobs’ earliest ventures involved building a device that allowed individuals to spoof identities on telephone networks.

The internet required mechanisms to verify personal identity because the information superhighway only became valuable when it could enable commerce. Conducting meaningful business requires knowledge of customer details.

Shopping on Amazon requires your address. PayPal agreed to be acquired by eBay partly due to rising fraud risks associated with its payment product. For the internet to grow, trust became mandatory. Establishing trust requires knowing who you're interacting with.

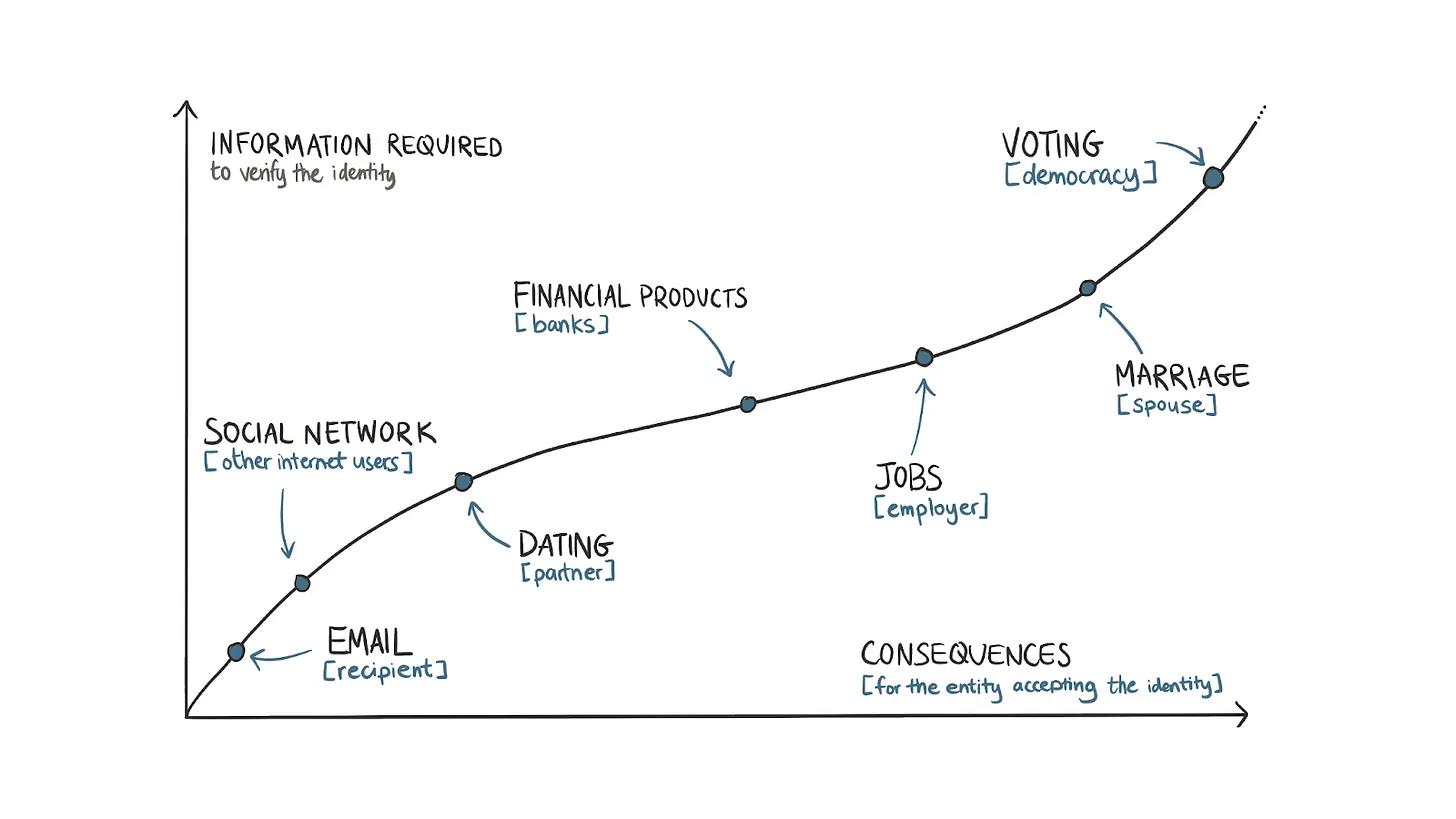

Internet applications collect identity information proportional to the potential consequences of user actions. It’s a spectrum. A simple Google search only requires collecting your IP address. Sending emails to 100 people requires your email provider to know your phone number. Making a payment via PayPal requires submitting government-issued ID. Regardless of your stance on privacy, it's fair to say that once a user base establishes identity, applications can scale.

Large networks like the internet grow when there is trust in the system. The emergence of different forms of identity strengthened trust, forming the foundation for a safer and more useful internet over the past decade.

From this perspective, we better understand why the amount of information collected during each interaction with the internet is proportional to the potential consequences of individual actions.

Accessing social networks typically only requires submitting a phone number. However, for verified accounts with wide reach, platforms like Twitter or Meta may require additional verification, such as government-issued identification. Similarly, because online accounts could facilitate illegal transactions, banks require information about employment and sources of funds.

At the absolute ends of this spectrum are marriage (at the individual level) and democracy (at the societal level). Assuming rational actors (which isn't always true), people gather as much information as possible about a life partner before marrying. Voter identities often undergo multiple rounds of verification because just a few thousand fraudulent ballots could sway election outcomes toward an otherwise unpopular candidate.

Today’s article explores a simple question: What happens when the forms of identity used in blockchain applications evolve? Much of the industry has been built on relative anonymity and open access. But as with the internet, having more user context is crucial for creating next-generation applications.

There are two reasons why on-chain identity becomes necessary:

-

First, market incentives continue driving individuals to exploit protocols through Sybil attacks. Limiting user access related to applications helps improve overall unit economics across industry businesses.

-

Second, as applications become more consumer-facing, regulations will require service providers to supply additional user information.

A simple heuristic here is that blockchains are fundamentally ledgers. They’re global-scale Excel spreadsheets. Identity products built atop them act like vlookups, filtering specific wallets as needed over time.

Network Identity

Every new network requires new identification systems. Passports emerged partly due to railway networks connecting multiple European countries after World War I. Even if we don’t realize it, we interact through basic identification units around us.

Mobile devices connected to cellular networks have an IMEI number. So if you make a prank call, the device owner can trace it back via purchase receipts. Additionally, in most regions, obtaining a SIM card requires some form of identity verification.

On the internet, if you use a static IP address, your name and address details are already linked to your online activity. These are primary identity identifiers online.

Single Sign-On buttons solved one of the web’s biggest friction points, giving applications a mechanism to obtain personal identity details without requiring repeated form filling. Developers can, with consent, collect details like age, email, location, past tweets, or even future activity on X platforms with just one click. This greatly reduced registration friction.

A few years later, Apple released a deeply integrated Single Sign-On button within its operating system. Users could now share anonymized email addresses without revealing their details to the product they registered with. What do these have in common? They all aim to learn more about users with minimal effort.

The more background an application (or social network) has on a user, the easier it becomes to target them with personalized offerings. The foundation of what we now call surveillance capitalism lies in the ease with which web companies capture personal user data. Unlike Apple or Google, blockchain-native identity platforms haven’t scaled yet because they lack the distribution advantages these giants currently possess.

Anonymity is part of blockchain’s feature set, but we’ve conducted identity checks on its periphery. Historically, converting on-chain currency to fiat (via exchanges) required collecting user information.

Blockchain offers native identity primitives that are unique because everyone has access to detailed user behavior. However, tools needed to identify, track, or reward users based on past behavior only emerged a few quarters ago. More importantly, products linking on-chain identity to real-world documents (like passports or phone numbers) haven’t yet scaled.

Over recent years, primitives used in our ecosystem to identify users include wallet addresses, NFTs, and more recently, Soulbound Tokens. They function similarly to IMEI numbers or IP addresses on the internet. The same person can connect a wallet to an app with one click. They resemble email addresses in the early days of the internet. In 2014, roughly 90% of emails were spam, with one in every 200 containing phishing links.

We use on-chain behavioral data from wallet addresses to create identity elements. Degenscore and Nansen’s wallet tagging are early practical examples. Both products examine historical wallet activity and assign tags.

On Nansen, you can scan token holders and see how many “smart wallets” hold the token, assuming a higher number of “smart” holders increases the product’s appreciation potential.

NFTs serve as identity tools due to their scarcity. In 2021, some “blue-chip” NFTs were limited to a few thousand mintings. Bored Ape NFTs capped at 10,000 total. These NFTs became symbols of identity by verifying one of two things:

-

Someone was early enough to mint and gain "Alpha."

-

Or they had the capital to buy the NFT on the market after minting.

NFTs became value symbols based on ownership. Bored Apes were owned by Steve Aoki, Stephen Curry, Post Malone, Neymar, and French Montana. The challenge with NFTs is that they are inherently static and community-owned. Since the Bored Ape mint in 2021, individuals may have achieved great things, but the NFT cannot reflect or verify this.

Likewise, if a community develops a poor reputation, NFT holders suffer. University degrees are similar to NFTs—both appreciate or depreciate based on the behavior of others holding the credential.

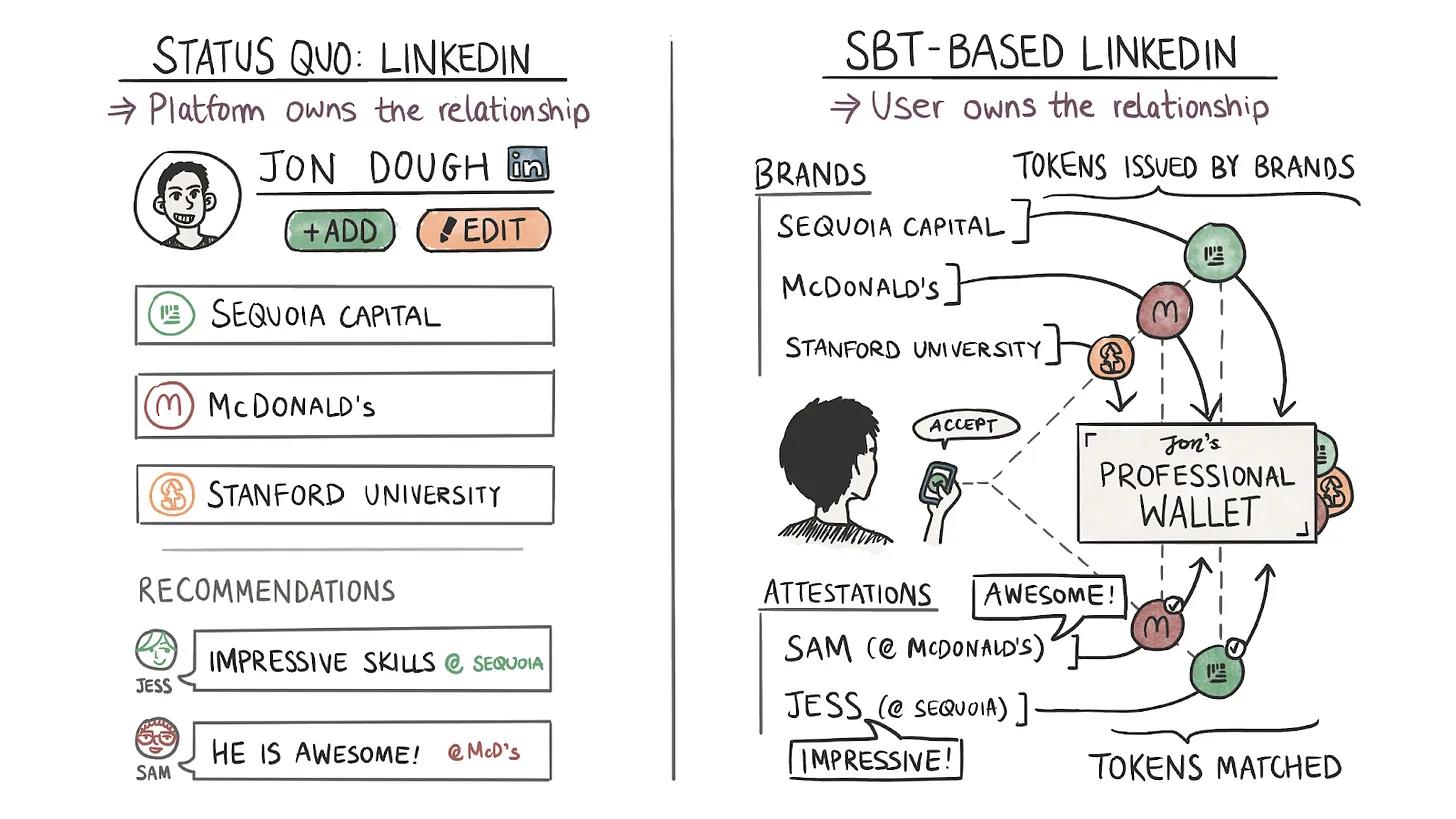

Vitalik Buterin proposed an alternative solution to this dilemma in his paper on soulbound tokens. Unlike NFTs, soulbound tokens (SBTs) are non-transferable. The key idea is that issuers (like universities) can issue certification tokens into wallets that cannot be transferred. Other token holders from similar institutions can attest to the SBT’s validity.

So if I claim I worked at McDonald's and have an issued SBT supporting that claim, a future employer can verify it faster than checking my LinkedIn or resume. If I have colleagues who use their SBTs to attest to this claim on-chain, I can further strengthen my credibility. In such a model, my claim is validated by the issuer (McDonald's) and by verifiers (colleagues) willing to stake their on-chain identity.

Like tokens and NFTs, SBTs are proofs of attainable status. SBTs being non-transferable means the wallet holding it possesses credentials that are earned rather than bought. In the example above, McDonald's certification likely isn’t available on OpenSea.

But if I have money, I can buy a Bored Ape NFT. The interesting thing about SBTs is that they can be mixed and matched to build social graphs. To understand this, we need to grasp LinkedIn’s core value proposition.

LinkedIn, like all social networks, provides status-as-a-service. People compete through profiles to appear as ideal corporate figures. LinkedIn’s genius was creating institutional social graphs early on. On that platform, I could claim I studied at Hogwarts with Harry Potter and Professor Dumbledore with just a few clicks.

One’s status on a social network depends on the reputation of affiliated organizations and their relative ranking within them.

In my hypothetical example, my reputation “strength” increases as I bind my identity to each new organization. As long as the network within those institutions achieves great things, my reputation grows too.

Why does this matter? Because today, nothing stops people from making false claims on LinkedIn. The social graph can’t be verified or proven, enabling spies from sanctioned nations to use it to target researchers.

A network of wallets holding SBTs could form a more decentralized and verifiable social graph. In the example above, Hogwarts or McDonald's could directly issue my credentials. SBTs eliminate the need for platform intermediaries. Third parties could build custom applications by querying these graphs, increasing the value of these credentials.

Web3 promises that open social graphs will allow issuers to establish direct relationships with credential owners. The chart above from Arkham visually represents all Bored Ape NFT holders. But if you wanted to contact them all, your best option would be exporting their wallet addresses and sending messages via tools like Blockscan.

An easier alternative might be browsing Bored Ape social profiles or their Discord, but this merely repeats the original challenges we faced with identity networks. If you want to scale, distributing anything through these networks requires centralization and permission from Bored Ape management.

All this brings us to the core problem of on-chain identity networks. Currently, none have reached sufficient scale to achieve network effects. Thus, despite having theoretical mechanisms to create open, composable social graphs and verify users via tokens, wallets, and SBTs, no Web3-native social network has managed to retain users and grow.

Currently, the largest “verified” on-chain social graph is WLD. They claim over 2 million users, but that’s only 0.1% of users on traditional Web2 social networks like Facebook. The strength of an identity network depends on the number of participants with verifiable identities.

Some nuance is needed here. When we talk about “identity” online, it’s a composite. Breaking it down:

-

Identification—the core primitive that uniquely identifies you. This could be your passport, driver’s license, or university degree. They usually verify parameters like age, skills, and location.

-

Reputation—in X’s algorithm, it’s a tangible measure of an individual’s skill or ability. This relates to the quality of content a person posts on a social network and how frequently their audience reacts. In work environments, it’s a graph of entities paying an individual (or entity) over time. Identity is typically fixed at a point in time, while reputation evolves.

-

Social Graph—think of it as the interconnection between one’s identity and reputation. A person’s social graph depends on who interacts with them and how frequently. Frequent interaction with high-reputation (or socially ranked) individuals leads to higher rankings on the social graph.

As with most things, even within internet identity, there’s a spectrum of applications.

Core Primitives

Although anonymity is part of crypto’s feature set, we perform KYC at crypto’s periphery. Converting on-chain currency to fiat (exchanges) has historically required collecting user information.

Exchanges are by far the largest on-chain identity graphs, tied to personal identification documents. However, it’s unlikely exchanges like Coinbase will launch identity-related products, as such moves could pose conflicts of interest.

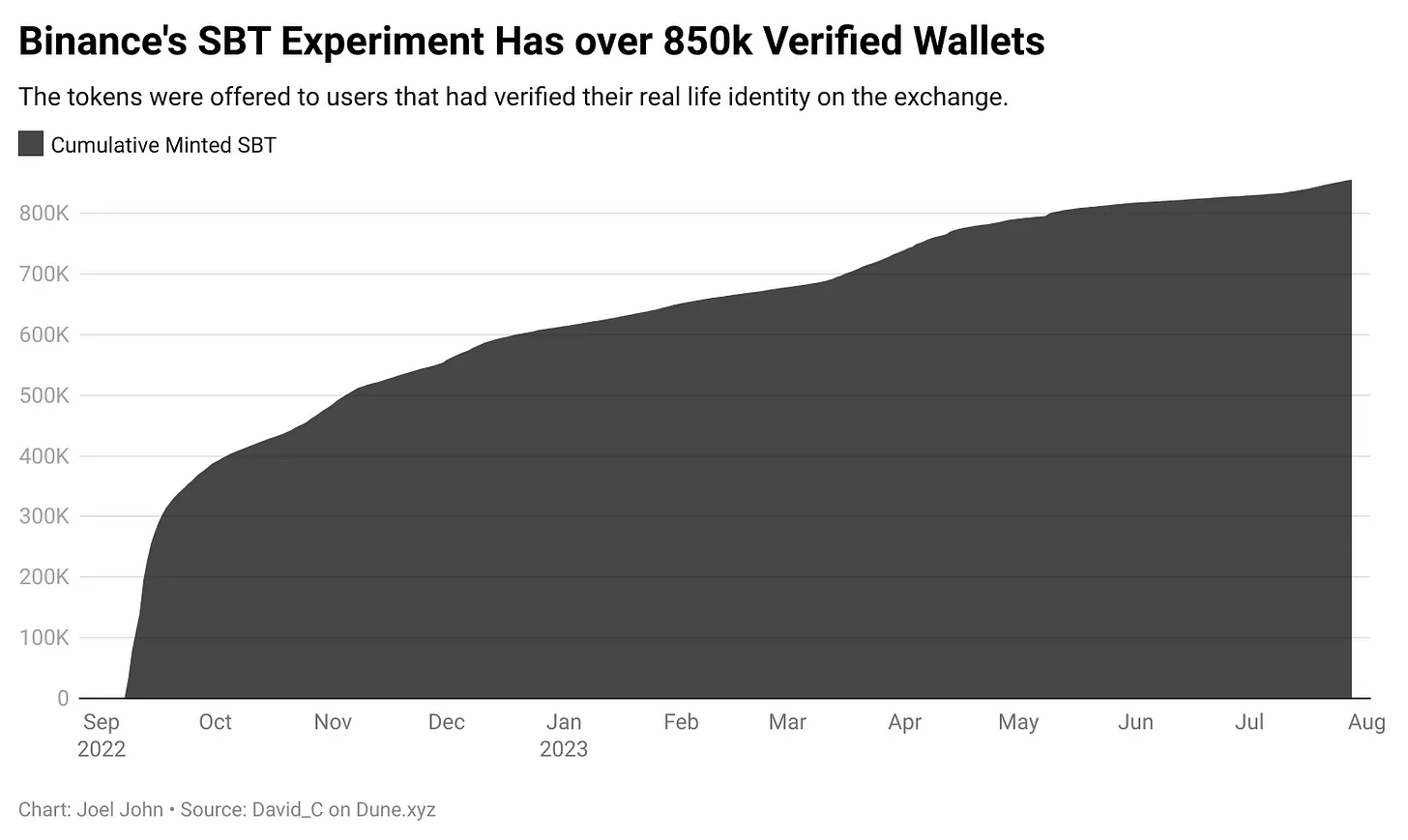

One of the earliest experiments with on-chain identity was Binance’s BABT. Specifically, Binance Account Bound Token is equivalent to a soulbound token (SBT) issued on Binance Smart Chain. It’s given to users who complete AML/KYC on the exchange. Over 850,000 wallets claimed BABT in the past year—an early attempt to link wallets to real identities at scale.

But why go through this trouble? It helps applications know users are “real.” By restricting access to users who’ve submitted verified documents (in the form of passports or regional IDs), products can optimize against arbitrage attacks and minimize impact from fake users.

In this case, dApps don’t access the user’s verification documents. This function is performed by exchanges like Binance, possibly using APIs from centralized providers like Refinitiv. For dApps, the benefit is having a subset of verified users who’ve proven themselves human.

Depending on context and available resources, methods for collecting and relaying user information to applications vary. Several approaches exist. Before diving deeper, grasping some basic terminology helps.

-

Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI)

Think of this as a design philosophy where credential owners have full control over their identity proofs. In traditional, state-recognized identity forms, governments or institutions issue and verify identity.

When someone submits ID, like a license for verification, the government system must not sever that connection. The core argument of SSI is that individuals should control (i) management, (ii) privacy, and (iii) access to their personal identity.

SSI-based identity products can include multiple identity forms—certificates from universities, passports, driver’s licenses, etc.—even if issued by centralized institutions. The core argument of SSI is that users should control how these details are accessed.

-

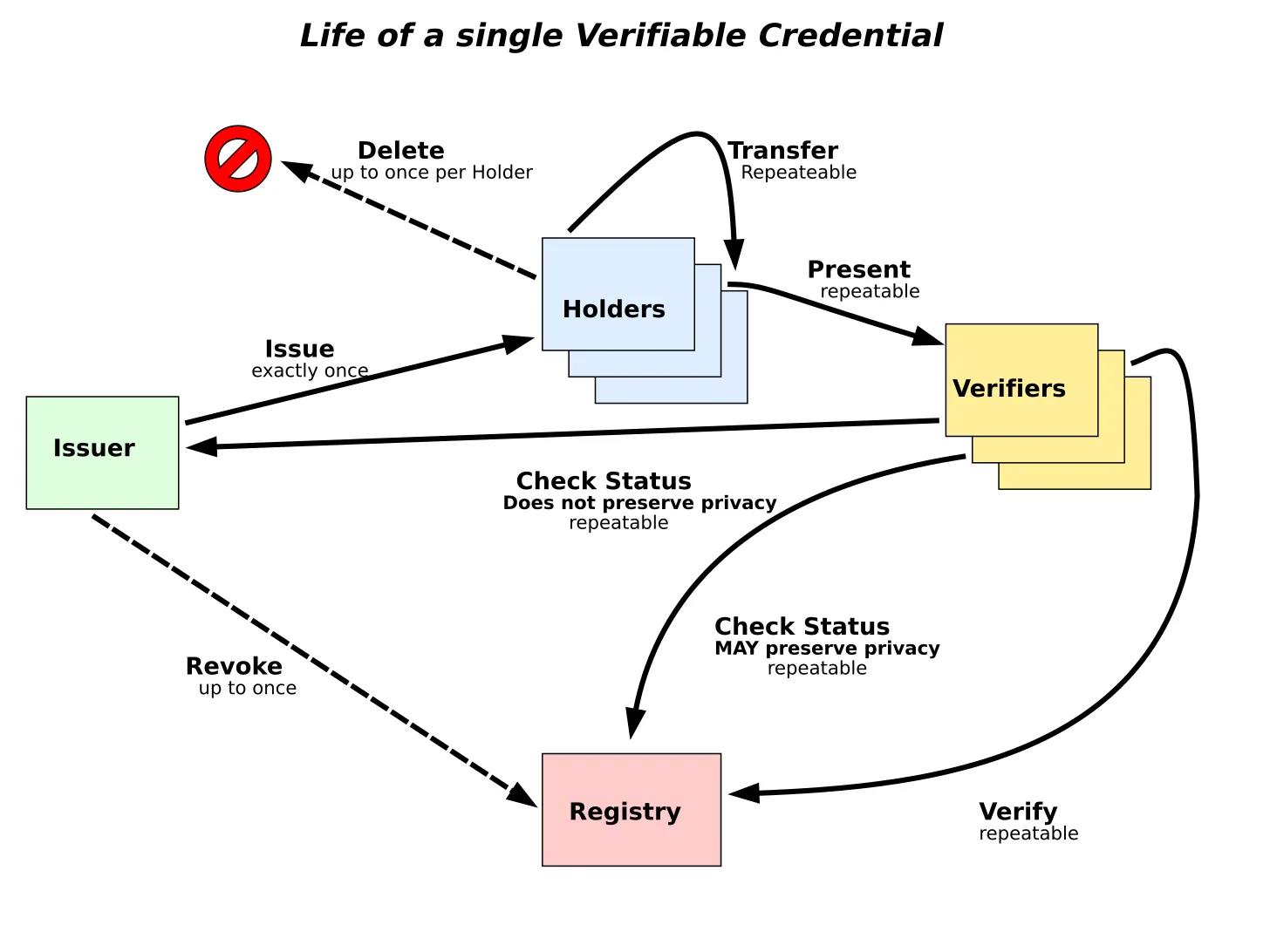

Verifiable Credentials

Verifiable Credentials are a model for cryptographically verifying personal identity. At its core, it consists of three parts: the issuer, the verifier, and the credential holder. An issuer (like a university) can issue a cryptographically signed proof to the credential holder. These proofs support so-called “claims.”

Here, a claim could be anything from “X studied here” to “Y worked with us for five years.” Multiple claims can be combined into a personal graph. With verifiable credentials, documents (like passports or certificates) aren’t transmitted—only the issuer’s cryptographic signature is shared to verify identity. You can see a live version of such a model here.

-

Decentralized Identifiers (DID)

Decentralized Identifiers (DID) are structural equivalents to your phone number or email address. Think of it as a wallet address for your identity. When using platforms requiring age or geographic verification, providing a DID helps applications confirm you meet usage criteria.

Instead of manually uploading a passport to Binance, you could provide a DID. Binance’s compliance team could verify the location proof held by the DID and register you as a user.

You might have multiple DIDs, each with independent identity proofs, just as you hold separate wallet addresses today. Tools like Dock allow users to store identity proofs and directly verify access requests from mobile apps. In this sense, users of blockchain-native apps are already familiar with signing transactions and verifying authenticity of identity requests. Another approach—ERC-6551—offers another way to manage isolated identity forms across wallets.

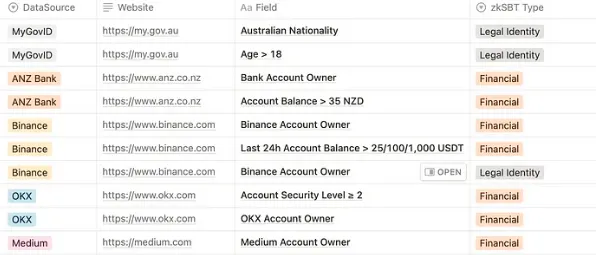

Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKP) let users prove eligibility without revealing details. Every time I apply for a UK visa, I must submit bank transaction records from the previous quarter. The lack of privacy for foreign visa officers handling my banking data isn’t widely discussed, but it’s one of the few ways to get a visa.

Proving you have sufficient funds to travel and return home is a requirement. In a ZKP model, the visa officer could query whether a person’s bank balance exceeded a certain threshold during a specific period—without seeing all their bank transactions.

This may seem far-fetched, but the primitives to execute this already exist. zkPass launched its pre-alpha version in July this year, allowing users to provide anonymous personal data (and verification files) to third parties via a Chrome extension.

Evolving Infrastructure and Use Cases

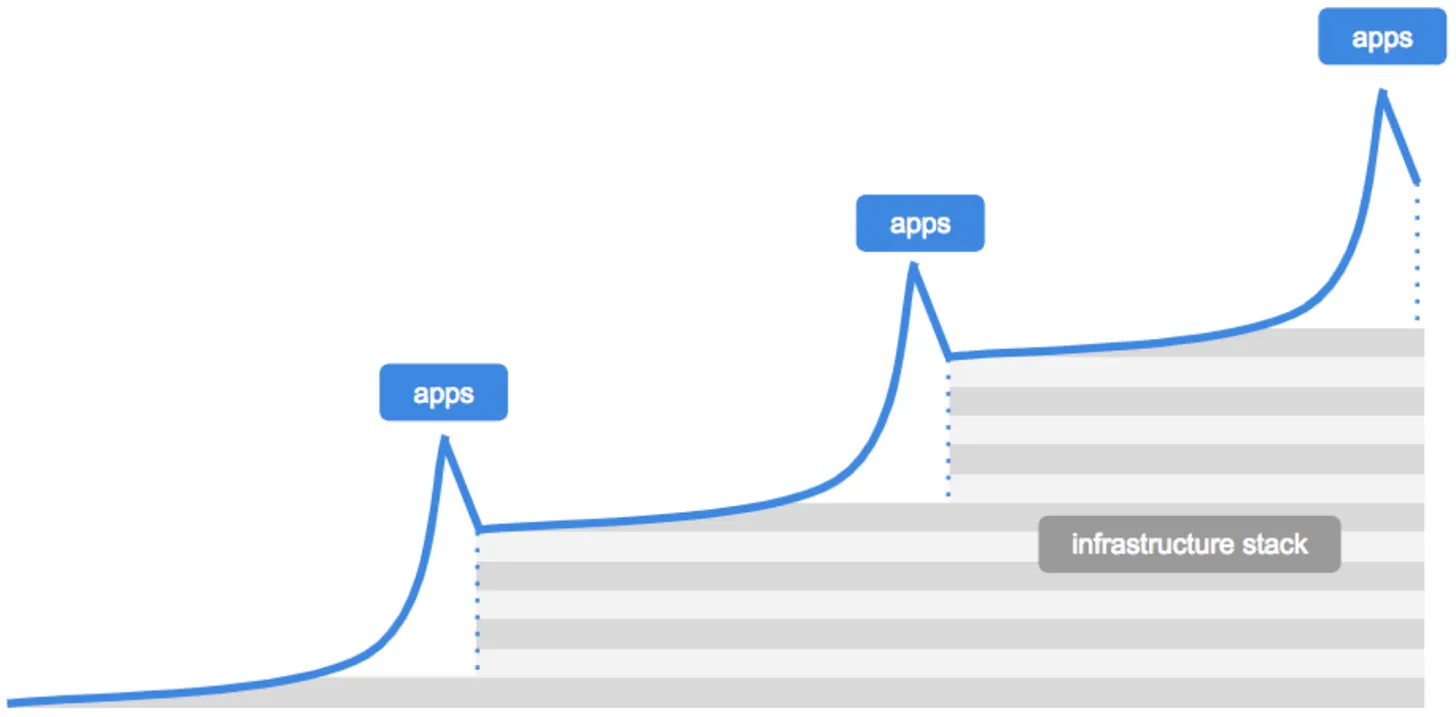

I could talk all day about the ecosystem of Web3 identity-related applications. Over the past few years, many developers have received millions in venture funding. But we’re not here to map the landscape of identity solutions—I want to focus on what the evolution of these identity primitives means for today’s internet. A 2018 blog post by Dani Grant and Nick Grossman at USV offers a good reference for the next phase.

According to them, breakthrough applications first emerge, demanding better infrastructure. This leads to improvements in the infrastructure layer to support scaling applications. Then, a new generation of applications builds atop this revised infrastructure—repeating until mature markets exist, as seen with blockchains and NFTs. In 2017, the Ethereum network ground to a halt due to CryptoKitties.

By 2021, high NFT prices justified the cost of NFT transfers. As of 2023, you can send millions of NFTs on Solana for under $100—a reason OpenSea has integrated Solana into its product over the years.

Historically, developers had little incentive to identify their users. Forcing users to submit documents would shrink their market size. Legal requirements have partially pushed many developers toward user identification.

Recently, Celestia’s TIA token airdrop banned U.S. citizens. Another reason for identifying users is to prevent airdrop farming by speculators. In both cases, emerging networks need primitives to prove who’s participating.

One primitive gaining widespread adoption is DegenScore. The product analyzes user history to assign a score. Applications launching on-chain can then enable wallet access based on user scores. This strategy limits people from creating hundreds of wallets to attack new products for airdrops.

This product isn’t an identity verification tool since it doesn’t check for state-issued documents. But it gives developers a mechanism to verify whether users should access their products based on historical behavior patterns.

One product combining off-chain identity with on-chain wallet addresses is Gitcoin Passport. Each time someone links an identity proof to their wallet address, the product issues a “stamp.” Stamps can be earned by linking Facebook, LinkedIn, or Civic ID. Gitcoin’s server issues verified credentials to a person’s wallet address. Thus, the product uses Ethereum Attestation Service to bring these stamps on-chain.

What’s the purpose? In Gitcoin’s case, mainly for grants. Given the product supports donations to public goods, verifying real users contributing becomes critical. Beyond Gitcoin, use cases include DAOs. Typically, someone could split their tokens across thousands of wallets and vote for favorable decisions. In such cases, verifying wallet humanity—either through past on-chain behavior or real-world identity links—becomes essential. That’s where Gitcoin Passport comes in.

Naturally, people don’t maintain a single identity across all applications. Having multiple wallets when using the same product is normal. Consider how many wallets you might use on Uniswap. Users also tend to switch wallets based on application type.

Separate wallets for gaming, media consumption, and trading are common. ArcX Analytics combines browser data (like Google Analytics) with smart contract interaction data from blockchains to help identify users. They primarily target developers wanting to understand user behavior patterns.

Tools for managing multiple identities are also evolving. ReDefined allows users to resolve their email address to a specific wallet they own. Their API lets developers create custom resolvers—meaning you could have products where a user’s phone number resolves to a wallet address.

Why does this matter? It simplifies building Venmo-like remittance apps. Users can upload contact lists (like on WhatsApp), and products like ReDeFined can map all phone numbers to on-chain addresses.

While writing this, I resolved my email address to a wallet address. Data linking which email belongs to which wallet isn’t stored on ReDeFined’s servers. Without logging in with my wallet, they can’t alter this resolution data. The resolution data is stored on IPFS.

You can link wallet addresses across different chains like Bitcoin, Solana, or Polygon on ReDeFined. The product detects which asset a user sends and routes it to the corresponding wallet on the matching chain.

But what if you want to identify and rank users on protocols like Lens? Ranking algorithms based on user behavior are already emerging in Web3-native social networks. In the late 90s, Google rose to prominence by analyzing the relative ranking of web pages.

It was called PageRank—a system that assigned reputation scores to websites based on how frequently they were referenced by others. Twenty years later, as web pages slowly became composable (through Web3-native social networks), we face the same dilemma with wallet addresses. How do you verify a user’s “value” on one social network using their activity on another? Karma3 solves this.

It helps applications (and users) figure out how to rank community members in DAOs or see which artists previously abandoned projects. Because the core identity unit (wallet address) is used across multiple protocols, Karma3’s product helps rank wallets. Thus, a user on Lens might not need to start from zero when writing on Mirror.xyz.

Reputation portability hasn’t historically existed on the internet. You might have 100k followers on Twitter, but starting on Instagram means beginning from scratch. This gives top creators little incentive to migrate to new social networks. It also partly explains why, despite relevance and demand, Web3-native social networks haven’t scaled. Discovery engines are broken, and incentives to switch don’t exist.

In models using Karma3’s product, new social networks don’t start from zero when relatively ranking users—solving the cold-start problem of attracting quality creators. Does this mean we’ll see an explosion of customized social networks? It’s possible.

So far, we’ve only discussed individual reputation—especially for individuals active on-chain. But what if we could create composable metadata for companies, queryable and displayable across different outlets? This already happens natively in Web2. As early as 2008, Crunchbase pulled company info from LinkedIn.

The problem is, in this case, nothing prevents Crunchbase from fabricating the data it displays on third-party outlets. You can “trust” the system because, in this hypothetical model, the outlet (like Crunchbase) has an incentive to present accurate information. Yet enterprise entities don’t control this.

This is especially important in the Web3 context, where traders often make decisions based on details found on Messari, CoinGecko, or CoinMarketCap. Grid is building a network of verifiable credentials for companies. In their model, companies can use private keys to upload details like investors, team members, funding raised, logos, etc., onto a sufficiently decentralized network.

Third-party data platforms like VCData.site can query information from Grid and display it to users. A key advantage of such a system is that enterprises don’t need to update details across multiple platforms. Whenever a startup updates its details using verifiable credentials, it reflects across all platforms querying its data.

Third-party validators (e.g., community members) will have incentives to challenge false claims in such a network. This remains theoretical and speculative, but the ability to uniformly update all company-related information across every mention is powerful.

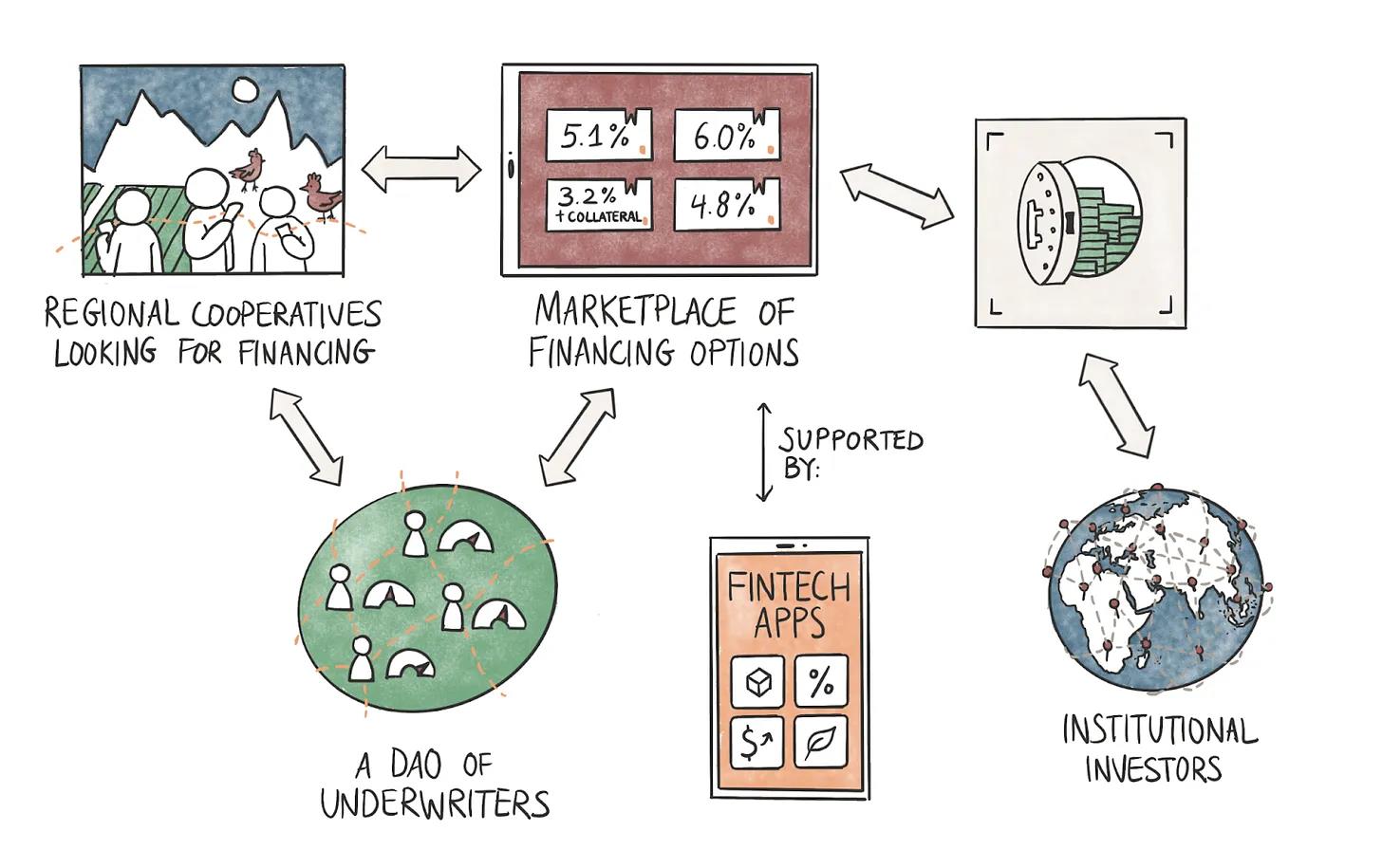

But what applications can such reputation primitives enable? A fairly simple example is real-world asset (RWA) lending.

The above flow shows how this might work in practice. Grameen Bank is a major lender to cooperatives in emerging economies. Partly due to social reputational risk from loan defaults by individuals. Cooperatives composed of women working with small businesses receive loans directly from the bank, maintaining revolving credit lines that grow based on repayment frequency.

In the 1980s, when digital identity wasn’t widespread, offering credit to unbanked individuals without collateral was revolutionary. In the 2020s, with the digital primitives we now have, this model can evolve.

In the scenario shown above, cooperatives can provide data to underwriters operating as DAOs. This data mainly includes their banking details, SME business transactions, and similar data points from Web2-native products. Tools like zkPass mentioned earlier can anonymize and deliver this data to underwriters, who can assess the cooperative’s creditworthiness and pass risk scores to the market.

The market can source liquidity from fintech apps or institutional investors seeking yield on idle assets. This can work in two ways:

-

A fintech company can directly lend to cooperatives with credit ratings from external underwriters.

-

An aggregator (or marketplace) can source liquidity from third-party fintech firms or institutional investors and offer loans based on credit ratings provided by underwriters.

In both cases, cryptographic primitives can ensure borrower data privacy. A DAO of multiple underwriters could facilitate loans faster than traditional entities if multiple parties race to assess risk. Finally, leveraging blockchain rails to tap into global markets could offer borrowers better rates. Our friend Qiro has been experimenting with such models.

Of course, this isn’t a crypto product per se. It’s a fintech primitive using blockchain technology. Historically, regulatory constraints and lack of identification on the internet prevented blurring the line between the two. As our primitives for tracking and identifying users evolve, the nature of applications buildable on-chain

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News