Volatility as a Service: Seeking volatility, embracing risk—that's the soul of crypto products

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Volatility as a Service: Seeking volatility, embracing risk—that's the soul of crypto products

As volatility declines, markets accustomed to taking risks become bored, driving users toward places where they can find volatility.

Written by: JOEL JOHN, SAURABH, SIDDHARTH

Translated by: TechFlow

Every now and then, I think back to Archegos Capital. The firm, founded by Bill Hwang—a former Tiger Cub—collapsed during last year’s market correction. Corporate bankruptcies in finance aren’t rare; they happen occasionally, and people eventually move on.

For example, the founders of Three Arrows Capital are now running an exchange while evading U.S. authorities after defaulting on loans. You get the idea—finance always has its oddities.

What made Archegos interesting was that Bill Hwang attempted to monetize “social” capital. He borrowed from multiple investment banks like Credit Suisse, using his stock holdings as collateral. The issue? Bill used the same pool of stocks to open separate credit lines with multiple institutions.

So instead of his $100 in equity supporting only $80 in credit, it backed up to $600. Classic leverage, you know how it goes. And then everything collapsed last year.

You might be wondering, what does this have to do with today’s article? The Bill Hwang case is an example of someone leveraging "social" capital to extract real money.

Historically, social capital and net worth were kept separate. Status could be bought and displayed through wealth. However, constantly talking about your riches was considered uncool. The media had already separated the processes of announcing wealth versus status.

For instance, the Midas List tells you how wealthy a venture capitalist has become. Or Forbes’ “30 Under 30” serves as a list of potential billionaires-in-waiting.

Historically, keeping social capital distinct from net worth was important. Not pricing influence maintained political and social order.

When markets “price” political power, we call it corruption. Today, crypto-native social platforms theoretically disrupt this relationship. This article explores why volatility-as-a-service is becoming a key theme in crypto applications and what the next few years may look like.

But first, take a look at the chart below. It explains many trends currently unfolding in the industry. Bitcoin's volatility is at its lowest since 2016.

This means most tools and products that thrived during high-volatility periods now struggle to retain users. Let me explain.

-

If people don’t believe Ethereum (ETH) will outperform Matic quickly, they have no incentive to borrow one digital asset (e.g., ETH) to hedge against another (e.g., Matic).

-

If the market doesn’t expect rapid swings in the short term, options trading volume drops nearly to zero.

-

If traders can't profit in the short run from trading an asset, perpetual contracts or decentralized exchange volumes dry up.

Most crypto products today rely on volatility to stay relevant. This isn’t a flaw—it’s a feature. Over the past decade, crypto’s core value proposition has been trustless value transfer. We’ve achieved that. Thanks to past volatility, the entire DeFi ecosystem was built, scaled, and profited during bull markets.

But times have changed, as shown in the chart above.

Rising interest rates, unemployment, and fatigue from multiple Ponzi schemes have dampened interest in existing product suites. There’s a reason for this. In bull markets, traders are incentivized to take on significant risk.

Products designed to cater to them naturally see high volumes. But as volatility declines, a risk-hungry market grows bored. Naturally, users migrate toward where volatility exists. This explains why products recently launched with volatility as a core feature have attracted the most attention.

Volatility as a Feature

The chart below shows user growth on Rollbit over recent months. The platform sees nearly 4,000 depositing users daily. By comparison, OpenSea averages around 6,500 daily users. This isn’t to say Rollbit dominates the gambling space. Rather, it reflects how users are shifting from NFTs to high-volatility products.

At the time of writing, Rollbit has seen ~$46 million deposited. Its token FDV stands at $800 million—nearly a 100x increase from a year ago.

Rollbit is a platform for trading volatile instruments and gambling, while Unibot caters to users seeking exposure to long-tail digital assets. Its value proposition is simple: it bundles together steps like setting up MetaMask, managing keys, logging into Uniswap, and finding the right token pair for fast trades—all accessible via Telegram.

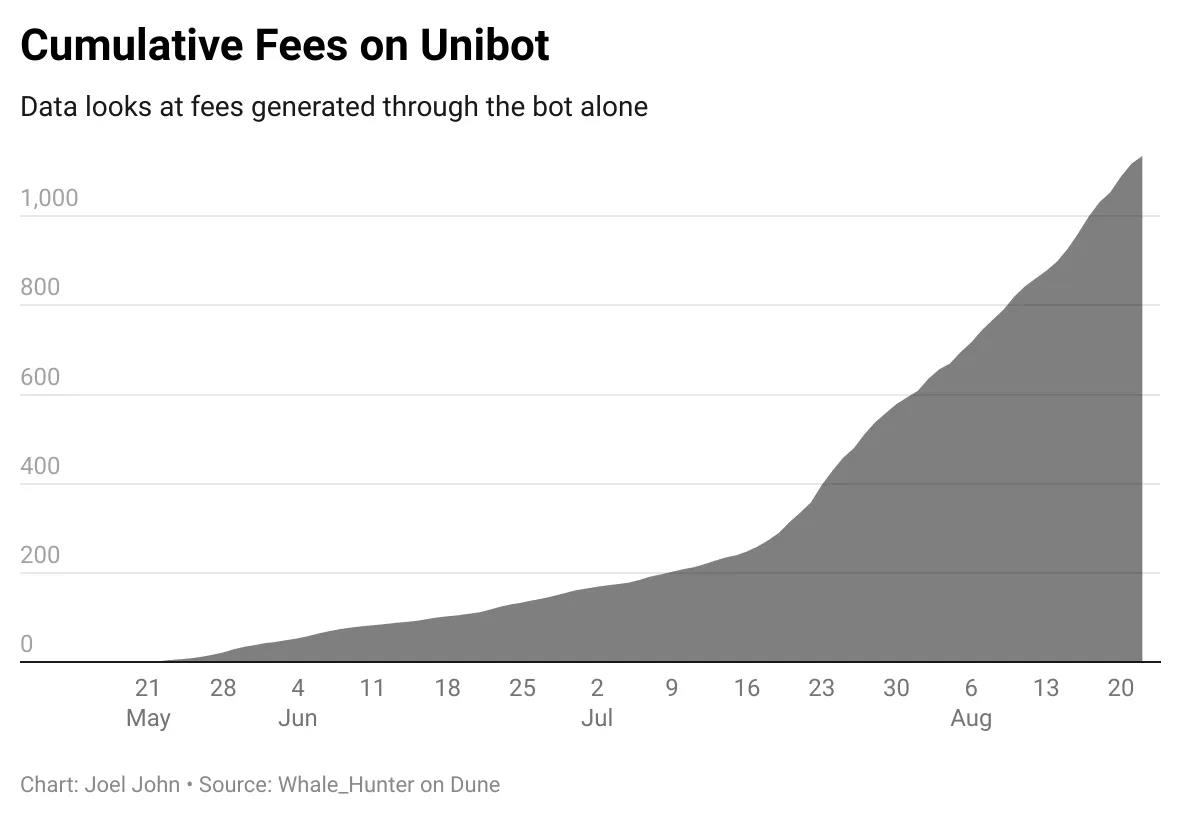

An average Unibot user generates ~$2,600 in daily volume, with each trade averaging ~$600. On one day, 3,400 users traded via Unibot. These numbers are far from typical exchange levels, but since May, it has generated nearly $2 million in fees.

Rollbit is a casino; Unibot is a tool for trading low-market-cap altcoins that lack volume on centralized exchanges. $PAAL, $DUUBZ, $RAT, $WAGIEBOT—do you recognize these names? Probably not. Yet these tokens saw the highest trading volume on Unibot in recent days.

What makes Unibot interesting is how it disregards much of traditional crypto wisdom. Private keys are sent in plain text over Telegram. The product uses a conversational interface instead of Binance-style complexity. It doesn’t even require login setup!

To buy a token, you simply paste its smart contract address. Yet it achieves nearly $5 million in daily volume—a feat most VC-backed DeFi products struggle to match.

Similar ideas are being applied to apps built on Telegram. They’re capturing attention and capital. Native crypto traders spend most of their time on Telegram. A UI combining new token launch alerts, MEV protection, and conversational ordering would be extremely powerful.

But to me, it reveals a different truth. Due to low volatility, crypto capital pools are moving further up the risk spectrum across different products.

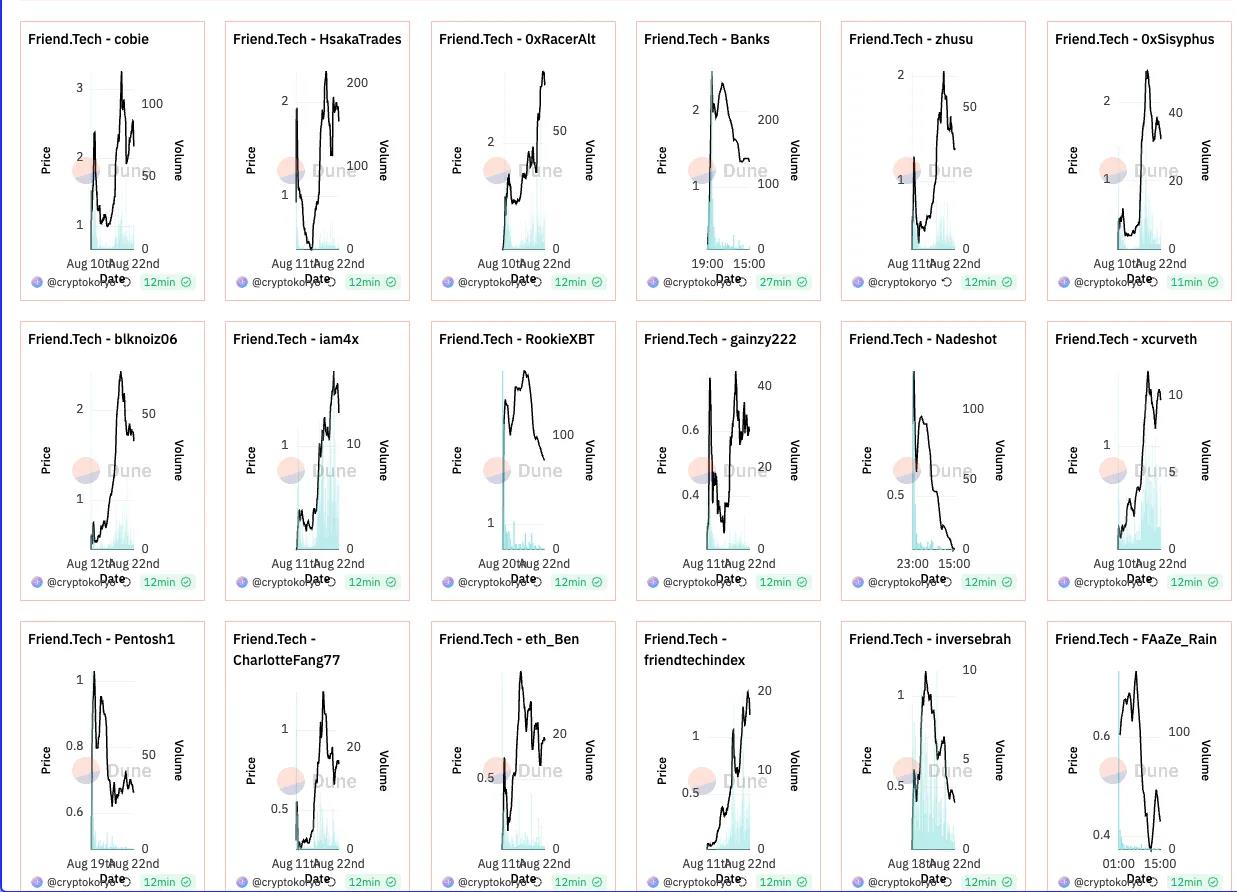

This becomes even more evident with FriendTech. Here are some key stats:

-

In the past week, top creator Cobie earned $142,000 on FriendTech.

-

A total of $52 million flowed into the product. Around $2.7 million in fees were distributed to users.

-

There were 1.4 million transactions involving 113,000 buyers and sellers.

All of this happened within a product less than seven days old. Compared to Lens Protocol, FriendTech had ten times more active users in the past week. According to Token Terminal, FriendTech has 100,000 verified users who log in via Twitter, while Lens has only ~9,000. Like most social networks, it also exhibits an emerging power law.

The chart below shows how much top “creators” earned on FriendTech last week.

Here’s what FriendTech got right:

-

Without support from backers like Paradigm, the market might have ignored this social app. Their involvement gave the product “signal” value when attracting influencers.

-

The product clearly involved influencer partnerships. Aligning with individuals who have massive reach helps drive narrative momentum.

-

Launching on Base instead of Polygon (where Lens currently resides) was a smart move.

Given FriendTech’s stage and early traction, it’s the most watched chain. They could’ve leveraged Lens’s social graph but chose to build their own.

Could the product be built on Arbitrum, Optimism, Polygon, or other L2s? Possibly. But none of those protocols have captured attention like projects on Base.

Status and Capital

I showed you all these numbers for a reason. Crypto culture runs on capital flows. That makes sense. We’ve built technology enabling global settlement ledgers, so there’s incentive to create products that use them.

If funds can’t be used for real-world goods, what’s the best use of moving money around? Well, you can invest it. Compress the growth (or decline) of those investments into short cycles, and you’ve got a narrative casino.

Everything is gambling; the difference lies in timelines and odds. Crypto sometimes uses shorter timelines and worse odds.

Over the past few quarters, new narratives emerged around various tokens. NFTs, GameFi, AI, infrastructure—each quarter brought fresh stories. Partly because we love narratives.

Even without fundamentals backing a token, having a shared narrative helps sustain belief in trades that could wipe out your net worth. You lose money on a bad trade, but at least it had a strong story behind it.

Tools like Unibot, Rollbit, or FriendTech solve for missing stories and volatility. FriendTech takes it further, possibly pointing toward the future of Web3 social products.

Eugene Wei’s concept of “Status as a Service” offers a powerful framework for understanding the evolution of social networks. In the early 2000s, it seemed plausible that social networks would mirror traditional ones. Yet reportedly, there were close to 300 different types of social networks back then. Remember Orkut, MySpace, and Friendster?

They all ended tragically, much like many altcoins in 2017. So what made Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok different?

Eugene’s essay is a masterpiece worth reading—I’ll summarize briefly. But first, take a look at the image below.

According to Eugene, successful social networks excel in three areas: high perceived social capital (status) for content creators, high entertainment value (dopamine), and some form of utility. Quora gives you answers, Pinterest boosts confidence in your taste, TikTok makes you ponder whether humanity’s future is worth waiting for.

These apps satisfy all three criteria.

But how do you assign status in a new application? You need proof of work. In the early stages of a social network, those who can demonstrate work become the “elite.” For example, TikTok primarily attracts young users because dancing on the app earns more views than posting long videos on YouTube (like Ashwath Damodaran).

Conversely, text-based platforms like Twitter or Substack grant status to those who write fluently. Bill Bishop’s Sinocism was one of Substack’s earliest publications. It conferred more status on the publication than the author, as Bill was already a successful writer. Years later, during Covid, when Packy launched Not Boring, Twitter celebrated his writing talent.

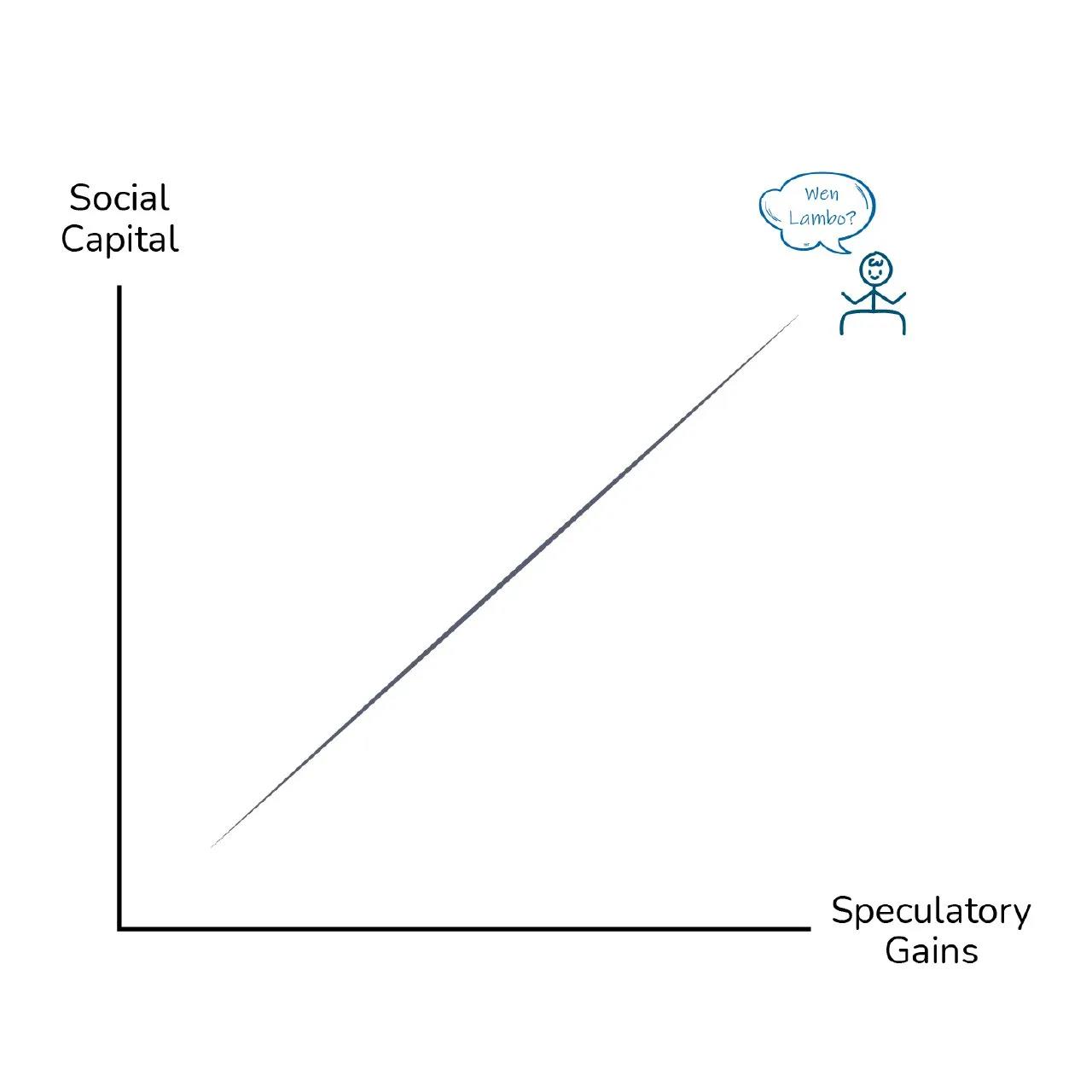

Status on social networks heavily depends on the skills required for proof of work, context-dependent. In crypto, if you're a trader, speculative gains roughly equal "proof of work."

All social networks initially compete among those capable of producing proof of work. Take Thread’s recent launch. I spent half a day on it, thinking Meta’s Twitter clone could be a great distribution channel for this newsletter. To my disappointment, the product violated two of Eugene’s core principles.

-

Threads grants status to individuals who are already influencers on Instagram. The product is built around posting curated photos and fun videos. Users with large followings on Instagram gain more followers on Threads.

-

Due to differences in background, style, and content, users on Threads no longer derive meaningful utility from the product. People can go to Instagram for edited photos. Real writers don’t see their audience on Threads, meaning they have little incentive to leave Twitter (or Substack) and restart on an influencer-dominated platform.

For well-performing users on Threads, the “competition” on the platform is neither fair nor equal.

As I write this, Threads’ active user count has dropped from 50 million at launch to 10 million. To get people to “work,” they need verifiable rewards and a fair game. A social network crosses the chasm only when enough people invest effort and find an appreciative audience.

Web3-native social products have long claimed “utility” due to features like:

-

Composability – Users can interact with content via multiple clients.

-

User Ownership – An account on Lens Protocol is unlikely to be taken down by a centralized company.

-

Decentralization – Storage and query layers are relatively distributed compared to Meta running Facebook or WhatsApp servers.

Other attributes include censorship resistance and immutability. But I’ll stick to these three core traits because without censorship resistance, large-scale Web3 social products are impossible. The problem is these “utilities” aren’t enough to attract users willing to publish content.

Today, users post on Twitter (or Substack) because that’s where the eyeballs are. Discovery, appreciation, and engagement are the “utilities” of Web2-native platforms. Traditional social networks are dopamine machines. Users willingly let centralized providers exploit their data because they receive more attention than on decentralized platforms.

Creators accept these trade-offs on Web2 for scale (attention). In the current environment, the only way to shift creators from Web2 social to Web3-native infrastructure is through capital. Money itself is a strong incentive and a precursor to social capital.

FriendTech’s genius lies in replacing the need for “utility” with capital.

One could argue crypto is inherently entertaining. We make many mistakes, but entertainment is something we’ve figured out. I’ll remove the entertainment axis from this chart and focus solely on comparing social capital and speculative gains.

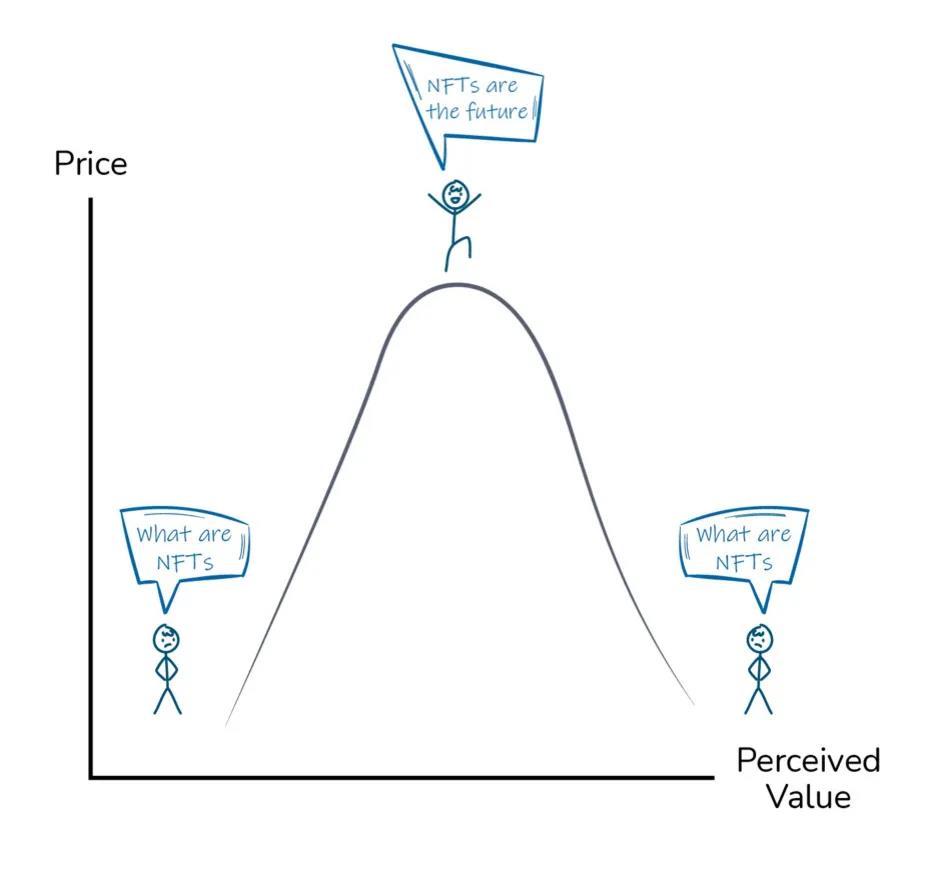

DAOs and NFTs followed very similar trajectories early on. Early participants gained massive speculative returns, which translated into status. As narratives faded, the possibility of making money by buying NFTs like BAYC diminished.

Users who bought BAYC on launch day had little status but reaped the largest speculative gains as early adopters. Once status was established through celebrity endorsements, available profits declined. Buying at peak meant only one outcome: loss. The chart might look like this.

At its peak, NFTs like Bored Apes conferred status. Their utility lay in access to elite networks—signaling either early minting or sufficient wealth to buy in at the right time. Your status depended on who else held the NFT. But as prices crashed, this “utility” (in terms of status and networking) vanished rapidly.

Social networks like Meta eventually removed NFTs from their platforms due to the negative status associated with them. Bored Apes became synonymous with scammers on Twitter, no longer a status symbol. Instead, they became anti-signals, with countless ape owners selling their NFTs (often at a loss) and reverting to original profile pictures.

Viewing NFTs as primitive Web3 social technology is one way to think about it. They map users and provide a simple social network (or community) based on ownership. The problem with these networks is that user incentives align directly with profits from holding these primitives. As prices collapse, the perceived value of the NFT-holder social network collapses too—an inverse Veblen effect.

A different class of Web3 social products avoids this trap by removing (or limiting) speculation. Lack of algorithmic feeds means excellent content posted on platforms like Mirror won’t be discovered by others. Unlike Substack or BeeHiiv, most Web3-native social networks adhere to neutrality and fail to attract creators with meaningful incentives.

This means users posting on Web3 social products may lose both status and potential earnings, since distributing content via platforms like Twitter could lead to business opportunities.

Mirror’s cleverness lies in allowing users to issue NFTs and potentially monetize. However, NFTs offer limited one-time sales revenue for creators. You might hope for royalties to fund ongoing work, but that’s speculative, not guaranteed. Thus, despite rich functionality, unless you’re a known creator, the platform fails to attract users in terms of status and speculative gains.

The chart below summarizes my view of Web3-native social products. When a product can’t generate wealth or distribute content effectively, it fails as a dopamine-inducing machine. Users will stick to existing platforms (like Twitter) rather than try new ones.

A product could be built on a chain enabling millions of transactions at near-zero cost, allowing users to own, filter, trade, or lend their data. But until incentive alignment is solved, users won’t flock to it. Utopian visions of technological progress rarely materialize until user behavior is thoroughly understood.

In the past, token communities were “social networks” of aligned individuals. The product was the token price. Today’s social networks aim to transcend the niche of “token investors.”

The more retail users our products attract, the further we drift from design choices once considered normal within past communities.

Merging Worlds

Historically, your on-chain social graph never interacted with your off-chain one.

FriendTech explicitly merges Web2 social graphs with Web3 social products. It leverages users’ Web2 social graphs to promote itself by posting tweets from their Twitter accounts without explicit consent.

By doing so, the product successfully完成了 the historically hardest part of launching a social network from scratch: finding friends. When you sign up for TikTok, Instagram, or recently Substack, the product requests permission to sync your phone contacts.

It then maps phone numbers to platform users and suggests them as friends. WhatsApp goes further, letting you message users whose numbers are saved in your phone.

By merging your off-chain social graph with on-chain actions, the product reduces the “activation energy” needed for user addiction. Users no longer waste time setting up wallets. One of your first actions is to “buy” shares in yourself, setting expectations for what the product wants you to do.

From there, you can use Explore or Trending sections to find friends. Those friends then get notified you joined, creating incentive to buy your shares.

The higher your share value, the greater the status conferred. What’s fascinating about FriendTech is that it assigns a publicly verifiable commercial price to people’s social graphs. It’s not just about graph size. Cobie has ~740K Twitter followers, while 0xRacer has only ~16K—but the latter has a higher market cap on FriendTech.

The product validates willingness to pay for your shares. It measures where followers are willing to spend money (attention)—a purer gauge of popularity. In an era where everyone gets 15 minutes of fame, creators earning $100K in royalties stand apart.

FriendTech is a conduit converting your social capital into speculative gains. The chart looks closer to the one below. Historically, making big money trading altcoins meant little outside crypto circles. Web3 social products like FriendTech blur the line between real-world influence and wealth generated from on-chain behavior.

Historically, we thought of the “on-chain” world as a limited subset of wallets. Depending on category or timeline, user counts for these product categories ranged from 4 million (DeFi) to 15 million (NFT). By blurring boundaries between Twitter social graphs and blockchains, FriendTech has unleashed the cat (the previous cat was Bitclout—I know how that ended).

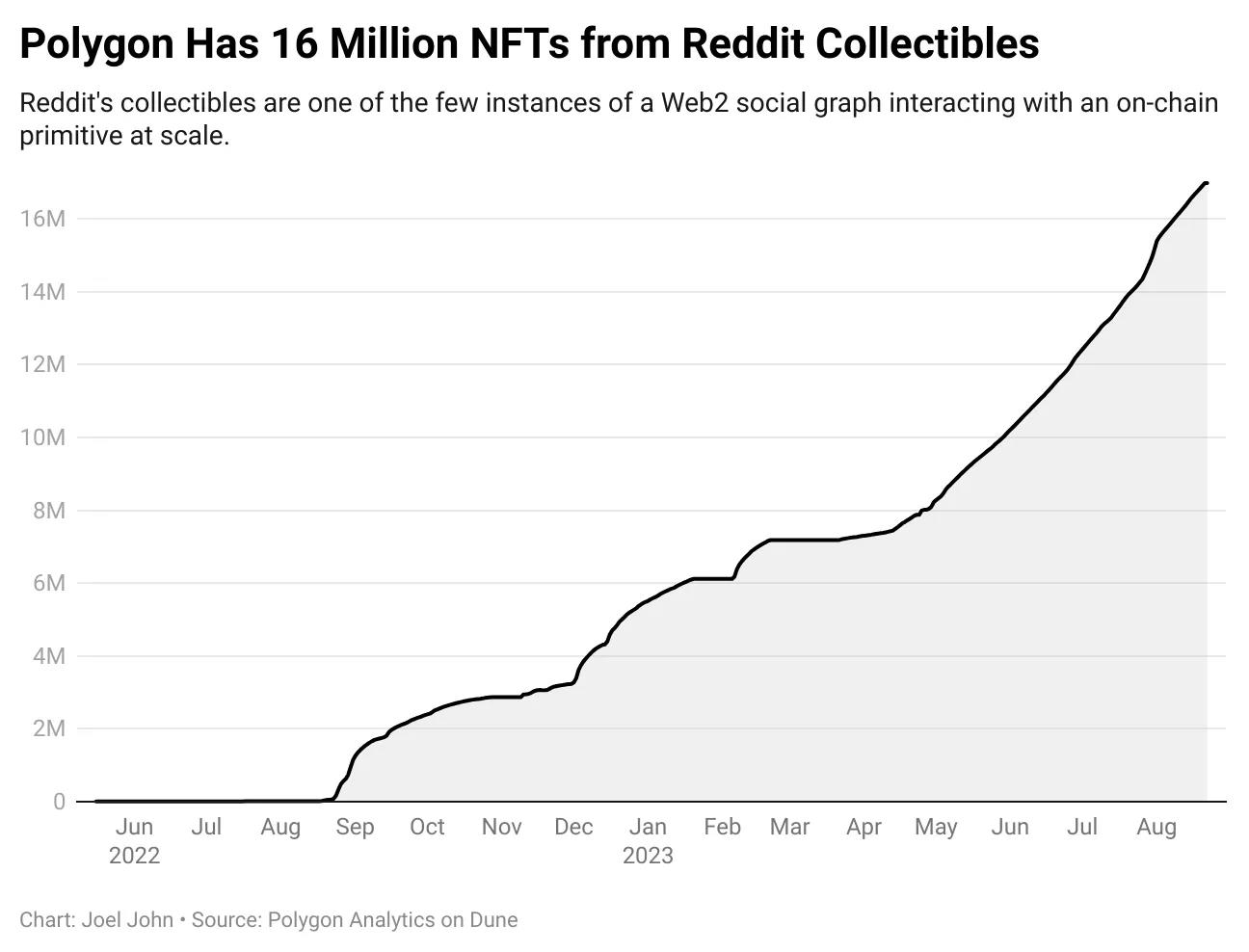

This “trend” of merging social graphs isn’t new. Twitter integrating NFTs into its product, Meta attempting to link NFTs to profiles—these are all variants of social graph fusion. But Reddit did it particularly cleverly. 16 million NFTs have been minted on Reddit without triggering a speculative frenzy.

The next wave of Web3 social products will similarly combine social graphs with volatility to accelerate growth. Mirror could integrate Twitter graphs. Lens (or apps built on it) could discover your Twitter followers via Lens handles.

But until speculation drives large-scale capital inflows, most of these products will (unfortunately) fail to capture sufficient attention.

If a product has enough utility, social networks can sustain themselves after users tire of status games. Instagram adopting disappearing photos (Snapchat) or Reels (TikTok) exemplifies how social networks expand their suite post-status-game to stay relevant.

Web3-native social products must rely heavily on capital inflows precisely because such utilities haven’t yet been established. Until a sufficiently large social graph emerges to retain users, volatility is a service.

Risk-Taking Behavior

Online products fully mature only when users start joking about each other. This happens everywhere—from YouTube comments to Amazon reviews, even Uber. Web3-native products haven’t reached sufficient user diversity to foster new friendships. Instead, we may end up with capital pools whose long-term value remains uncertain.

You can monetize content without crypto. You can run a paid Telegram chat. There’s no need to use bonding curves to monetize your content. I doubt any creator needs Friend.tech to become better at creating. Consider: John Lennon, Beethoven, and Michelangelo all relied on financial elements during their careers. Yet they didn’t need an on-chain Ponzi scheme to succeed. Web3 social products will financialize everyone. Is that desirable? I don’t know.

Historically, to create wealth, you either launched a protocol (like Aave) or ran a community (like BAYC). Web3 social will let anyone generate wealth from their social graph with just a few clicks. Given legal risks, many high-following creators may avoid jumping in, leaving the space dominated by a small group of risk-tolerant financiers.

Remember Threads? We might soon see the same pattern in Web3 social.

This means we’ll continue seeing risky behaviors involving money and reputation. NFTs enabled celebrities to issue digital assets and monetize their social graphs. But they also led to countless scams. Like all nascent technologies, we’ll experience a mania phase where Web3-native social products are hailed as the future of content.

For FriendTech, I remain skeptical—for now. LooksRare, Blur, and many others previously humbled me. You start optimistic, but once incentives (airdrops) end, users move on. As long as air drops and royalties are involved, you can’t verify how many users are genuine. FriendTech has an airdrop tab. Creators on the platform are incentivized to distribute widely due to royalty structures.

Currently, one of the worst outcomes for FriendTech could be a reverse network effect. If most users holding a creator’s shares incur losses, the incentive to engage weakens. Making money as a creator is great. (Believe me, I know.) You need to pay bills. But having a portion of your audience disinterested in your content becomes punitive. Tools like FriendTech now let users build portfolios via social graphs. And like our crypto wallets, those portfolios may suffer massive drawdowns.

Historically, creators competed with other creators for attention. Web3 social products combining trading, reputation, or content will shift competition away from one scarce asset: people’s willingness to spend time on your content.

I’m skeptical, but it’s increasingly clear that volatility is one of the strongest entry points for Web3 social products.

Here’s why. In the past week, ~100,000 people signed up for FriendTech. These users sought risk, not content. You can build excellent products targeting retail participants. But they lack crypto context. The only way for a product to achieve growth sufficient to trigger large-scale network effects and attract retail users is by drawing in crypto-natives and making them rich via product royalties or airdrops.

Whether we like it or not, this process involves speculation. We can ignore it, but people care less about decentralization than we assume. They care more about what the product does for them than the number of PhDs deciding consensus mechanisms on a blockchain.

In crypto, the “tone” has always been volatility. Web3 social combines volatility with social graphs. It may trigger collective madness. Thinking about how this might unfold scares me. But like most tech cycles, I believe it may breathe new life into long-overlooked primitives like DAOs.

Until regulators act meaningfully, we’ll keep seeing developers blur the lines between acceptable and unacceptable.

Ironically, we’ve had such experiments before. Steemit and Bitclout come to mind. The NFT craze was another similar cycle. Assuming capital allocation patterns in new product categories won’t repeat is intellectually dishonest.

Crypto must evolve from a “trading” product to an “attention economy” product to reach today’s internet-scale user base. The tech stack must enable use cases that capture attention rather than money. Web3 gaming and social networks fit perfectly. We still lack mechanisms to attract creators with proper incentives.

In 1997, there were ~13 million people online. Today, there are 3 billion. Web3 social products are speculative platforms today because we haven’t yet learned how to attract ordinary users without making them lose money.

Most of the industry’s work isn’t in building new L2s or DEXs, but in discovering business models that leverage existing technology. Borrowing Janet L. Yellen’s words: speculation is a temporary feature.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News