Web3 Protocol Layer Value Exploration: Earning from Economic Models, or Providing Low-Cost Services to the Community?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Web3 Protocol Layer Value Exploration: Earning from Economic Models, or Providing Low-Cost Services to the Community?

If we believe blockchain is the infrastructure for transactions, and all online behaviors will become transactions, we may inevitably need low-cost protocols and fixed costs.

Written by: JOEL JOHN, SIDDHARTH

Compiled by: TechFlow

A protocol is a set of rules followed by participants within a system. For example, military protocols dictate how individuals should act. Diplomats follow a certain "protocol" in their interactions with one another. You can think of a protocol as a bundle of rules. In the context of machines—especially computers—a protocol is defined as a rule that governs how data flows. For instance, RSS is a protocol that defines how article updates are delivered to clients. SMTP defines how emails reach inboxes. Protocols are bundles of rules specific to a given context.

On the other hand, a platform is an operating system, social network (like Meta), or hardware (ARM/NVIDIA) that enables a set of protocols to run on top of it. When you use Outlook (an application) on Windows, you're using SMTP (a protocol) to transmit data over Windows (the platform). Currently, there is no Web3-native platform that has scaled significantly. Solana’s mobile devices might have their own operating systems fine-tuned for industry needs. Ronin has its own app store enabling distribution of NFT-enabled games.

However, when you consider the scale of Azure, Facebook, or iOS, you realize there is no platform in Web3 that comes close. (This may be because we simply don’t need them yet.) In 2019, both Samsung and HTC attempted to create hardware-supported mobile devices, but I believe demand for wallet-integrated phones has declined since tools like Secure Enclave became available.

What confuses me is the idea that applications can also be protocols. Take 0x, for example—is it a protocol or an application? Matcha is an application, while 0x is a protocol that multiple DeFi products can integrate with to access liquidity. Similarly, OpenSea has Seaport, a protocol allowing various NFT marketplaces to share liquidity. Do you see the point?

Because it's difficult for a protocol alone to attract multiple developers early on, developers often launch a companion application to drive activity. If you're just a standalone application, you’re likely to be replaced by another app. OpenSea lost the royalty war to Blur. But if you're a protocol with multiple applications built on top of it, the likelihood of being fully displaced drops significantly.

So, if you zoom out slightly, the strategy over the past few years has been relatively straightforward:

-

Launch an application. Drive liquidity through token incentives.

-

Once you’ve grown to a certain size, allow third-party apps to leverage your liquidity.

-

Release a protocol with a governance token.

Both Compound and Uniswap exemplify this strategy. Coincidentally, their core products were so strong that people didn’t feel the need to build applications on top of them. Products like DeFiSaver, InstaDApp, MetaMask, and Zapper route liquidity into these platforms. But most user activity still occurs on the original product—the native website of the protocol.

In such cases, teams build moats in two ways:

-

First, through distribution—they become the most prestigious brand in the industry.

-

Second, through network effects created by multiple applications sending liquidity to them.

In other words, in digital assets, applications can evolve into protocols (or even platforms). As roll-ups make it easier for applications to masquerade as L2s, we’ll see more and more apps claiming to be protocols in hopes of increasing their valuations.

Utility

During the ICO boom, there was no clear definition of what tokens should do. The general belief was that tokens shouldn't engage in activities that could classify them as securities—but beyond that, there were no firm guidelines. People experimented with dividends, buybacks, burns (like Binance), and governance rights attached to tokens. The core challenge lies in tying economic value to something that costs nothing to mint.

Transaction networks like Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Ripple can claim that a small portion of their assets is required to conduct transactions. As transaction volume increases, the value of the underlying asset (e.g., ETH, XRP) rises accordingly. The cost of transacting on Ethereum is akin to a low-cost Android device—if someone else is minting at the same time you're trying to transfer, you pay more.

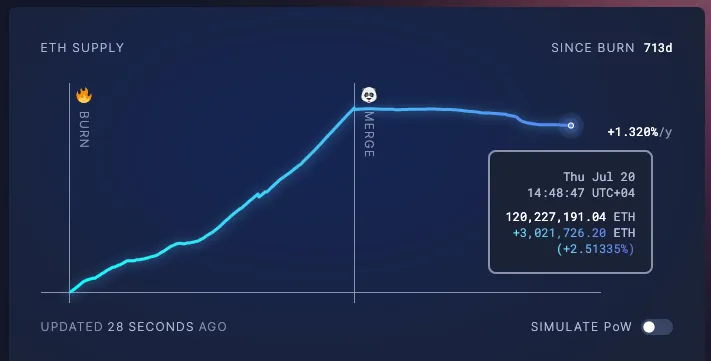

This framework helps value many tokens, whose worth is based on revenue generated from transaction fees. Ethereum’s EIP-1559 burns a small portion of token supply with every transaction, making it a deflationary network. This logic works well when you're a base layer deriving value from transaction volume.

But when you're not a transaction network but an application, requiring users to hold your native asset becomes a friction point. Imagine if your bank required you to hold its stock every time you took out a loan. Or if a McDonald's cashier asked how much of their stock you owned before handing you a burger.

Mandating that real utility be tied to holding a native asset leads to poor outcomes. Exchanges understand this well—that’s why Binance or FTX (RIP) never required you to hold their tokens to trade. They simply offered discounts for using their tokens to nudge behavior.

Many tokens we now call governance tokens are actually hidden utility tokens. That is, their utility stems from the idea that they can be used to govern the network itself. There’s ongoing debate about whether DeFi has truly decentralized governance, but the basic assumption is that holding an asset gives you a voice in how the product operates.

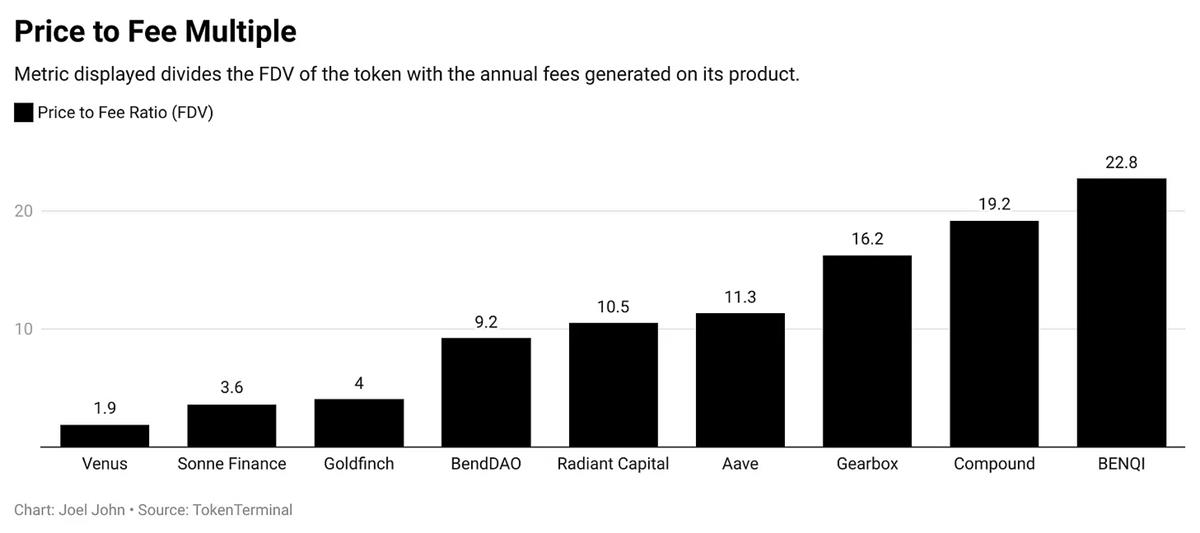

For many DeFi projects, this means being able to change fee variables, supported assets, and other financial parameters. In such cases, token holders don’t receive direct revenue from the product, but their tokens “govern” treasuries that may generate revenue. So if a product generates $100 million in fees for users, then in fair valuation terms, multiples based on that number become relevant. Compound and Aave’s price-to-earnings ratios align with those seen in publicly traded fintech companies. Markets are driven by narratives in the short term but revert to rationality over time.

Markets are narrative machines and periodically amplify hype. When this happens, a platform’s valuation is driven more by the narrative it can push than by the fees it generates. Simply put, if a thousand people notice that ten people are using a dApp, the token’s valuation might exceed the fees generated by those ten users.

This is because, due to the liquid nature of digital assets, capital allocators outnumber users. Take Compound: over 212,000 people hold its tokens in wallets outside exchanges. Yet only around 2,000 used Compound for lending in the past month. By Web3 standards, even this 1% ratio is considered healthy.

Ashwath Damodaran calls this the "big market illusion." In a 2019 paper, he explored how multiple venture capital firms bet on similar themes, assuming all their bets will eventually succeed. We see this now in AI.

Billions flow into multiple companies pursuing the same mission, assuming the market is large enough to sustain them all. VCs deploy capital hoping their startups will stand out with enough market share to justify higher valuations. Given the typical power laws in startups, many will fail. We see this play out in digital assets too.

When a small group of users emerges, individuals rush to trade an asset. Often, people assume utility will continue rising and catch up with valuation. Then, a new product appears with a shiny token airdrop. Users flock elsewhere, and valuations fall as markets reprice based on weak platform usage.

dApps vs Protocols

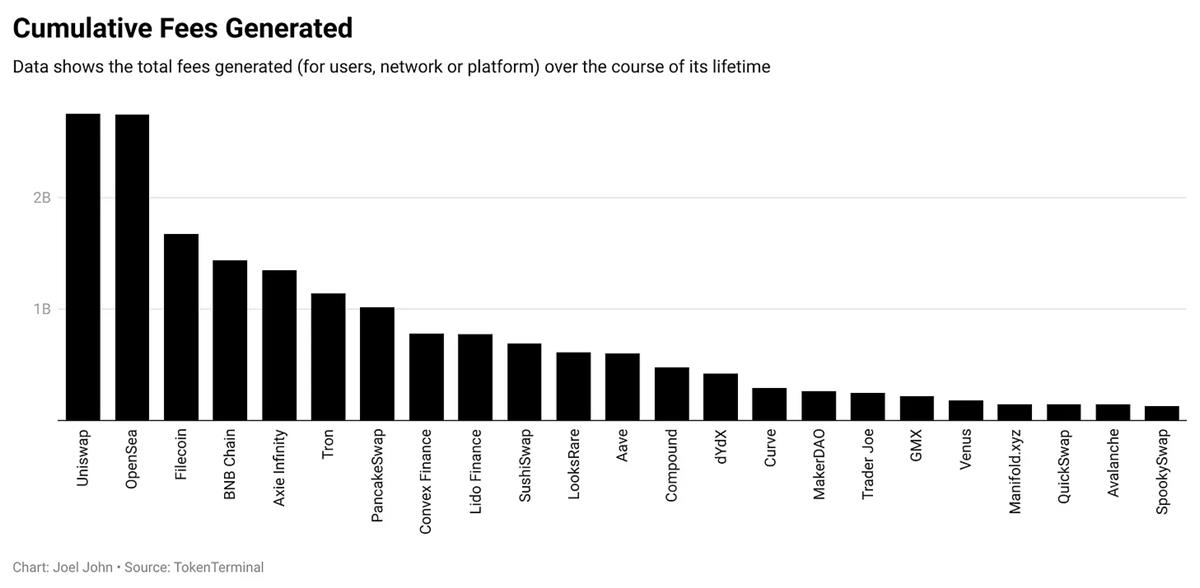

Now that we’ve established some basic economics of how protocols and applications generate revenue, it’s worth examining which of the two generates more fees. The chart above excludes Bitcoin and Ethereum due to their first-mover advantage, and Solana too, in case you're wondering. You'll notice that apps like Uniswap and OpenSea generate far more revenue than the average protocol. This may contradict the notion that protocols should be more valuable than applications because value flows downward (to the infrastructure supporting them).

That’s why citing the "fat protocol thesis" as justification for new Layer 2 solutions is flawed. Mature applications on Ethereum can generate more fees than relatively young entire protocols.

There’s a reason for this. dApps tend to earn money by capturing a small fraction of transactions occurring on them. Your revenue scales with the volume of capital flowing through the product and your fee rate. Uniswap and OpenSea earned nearly $2.8 billion because of high velocity of money (how frequently assets turnover) and enforceable fee structures that deliver value to users.

For protocols, raising fee rates as usage grows risks breaking network effects unless the use case justifies it. Let me explain. If your livelihood depends on Bitcoin, paying transfer fees equivalent to a week’s income in emerging markets might be acceptable. But once fees rise, it becomes unaffordable for everyone. Bitcoin’s immutability and decentralization are features people pay a premium for.

Bitcoin’s fee levels are justified by:

-

The Lindy effect of the network;

-

Its decentralization and immutability.

But when you introduce stablecoins issued by centralized entities, the market reprices willingness to pay for the protocol. That’s why Tron is the center of stablecoin activity. Here’s a way to quantify it: last week, the average USDC transfer amount on Ethereum was close to $60,000. On Arbitrum, it dropped to $9,000. On Polygon, it was just $1,500. Using "average" as a metric here is debatable, but the assumption is that as fees drop, sub-$100 transactions become feasible. My point is:

-

We assume protocols become more valuable as transaction volume increases and costs rise.

-

But high costs often break the network effects of user concentration on a single network, gradually pushing them elsewhere.

That’s why dApps on emerging chains have never reached critical mass in fee generation. When you launch a DeFi product on Ethereum today, you’re leveraging the network effects of users who accumulated wealth during the ETH era, ICO boom, NFT mania, and DeFi summer, along with robust infrastructure enabling trading, borrowing, and lending. When building on the latest trendy L2, you hope users bridge their assets and adopt your product. It’s like starting a business in a new country. Sure, less competition—but fewer customers too.

It’s like running the only Starbucks on Mars. Interesting? Probably. Profitable? Probably not.

Community as Moat

We’ve been deeply reflecting on what moats look like in Web3. Unlike other industries, most crypto applications are known for two characteristics:

-

Open-source: Anyone can copy what you've built;

-

Capital mobility: Users can leave anytime with their funds.

Despite these traits, Uniswap, Aave, and Compound have maintained relative dominance in their domains for years. Multiple DeFi products have copied Compound but failed miserably. So what’s their moat?

In this industry, the simplest measure of a moat is liquidity. If you’re a capital-intensive product, liquidity refers to the amount of funds available to facilitate trades. If you’re a consumer app like a game, liquidity is attention. In both cases, the key driver of liquidity or capital is community. Thus, in Web3, the only real moat is community. And what keeps early community members engaged is capital incentives or product utility.

Products like ChatGPT, which dramatically improve user experience, don’t need to incentivize users to attract them. Blockchain occasionally enables similar magic. DeFi crossed this chasm during the golden age of AMMs and permissionless lending, coming alive in June 2020—an era we nostalgically call “DeFi Summer.”

A large user base seeking quick profits via airdrops may resemble a community—but it isn’t one. Long-term, this is a “cost” to the network, because if you want to maintain price, buyers purchasing tokens must provide sufficient liquidity. For example, yesterday it was revealed that 93% of tokens held in Arkham Intelligence wallets were immediately moved. Are those sellers community members or a cost to the network?

They could become community members if they strategically repurchase. But as long as they don’t need the token to use the platform, they lack incentive to do so. They can allocate that capital to hundreds of other tokens instead. DeFi products like Compound and Uniswap don’t just have token-holder communities—they have thousands of individuals leaving billions in their liquidity pools.

You can copy their codebase, but without a committed community, you can’t replicate their liquidity pools over a sustained period. Capital incentives help retain community long-term.

Capital incentives reward users in tokens for performing functions on the network. For example, those providing Filecoin storage earn tokens for their contribution. Early participation is another form of capital incentive accumulation. Bitcoin and Ethereum are similar—early adopters amassed wealth through early involvement and holding patience.

User capital allocation needs are transcended through shared culture. Bored Apes and the countless GMs or WAGMI seen on Twitter during the last bull run are examples. Culture helps individuals align their identity with the project, keeping them engaged longer. Culture can’t be quantified, but the excitement seen around events like EthCC or Solana’s Hackerhouses exemplifies it. It gives individuals a mechanism to build, connect, and ideate without needing capital to participate in conversations.

Protocols can’t run on vibes alone—you need people building on them. Developers are where culture and capital intersect, serving as tools for long-term user retention. If you view a protocol as a nation, the utilities developers build keep users (citizens?) anchored to the network long-term. Protocols can charge fees, like tolls on highways. But if fees are too high, they’ll drive users away. From this perspective, it’s clear that if a use case is consumer-facing, the protocol may not be designed to profit at all.

Moats in Web3 are formed when users stick with a network over long periods to facilitate economic transactions within applications. Every network has the same set of dApps with different branding, selling “lower transaction fees” as their unique selling point. We’ll soon have decentralized ecosystems with fragmented user attention. Indeed, capital will briefly flow into these ecosystems via exchanges as users trade, but they’ll quickly turn into ghost towns like EOS.

In the real world, you can’t replicate a country. There’s no mechanism to expand land area within borders (without violence or economic integration). That’s why people are forced to concentrate in central hubs—historically ports. London, Mumbai, and Hong Kong are all similar in this regard. Concentration drives network effects within cities. Rents surge, but that also means faster grocery deliveries and better services.

In the digital realm, due to how intellectual property works and the expansion of product suites, users are funneled into a single ecosystem. Google launched its search engine, Gmail (2004), Android (2005), YouTube (2006)—all reinforcing stickiness to its ecosystem. Signing up for Gmail inevitably pulls users into other Alphabet products. Apple and Meta employ similar strategies to lock users into their ecosystems.

Apple takes it further by owning the entire stack from hardware to payments. Concentrating user bases enables economies of scale. I mention this for a reason—and it comes back to developers.

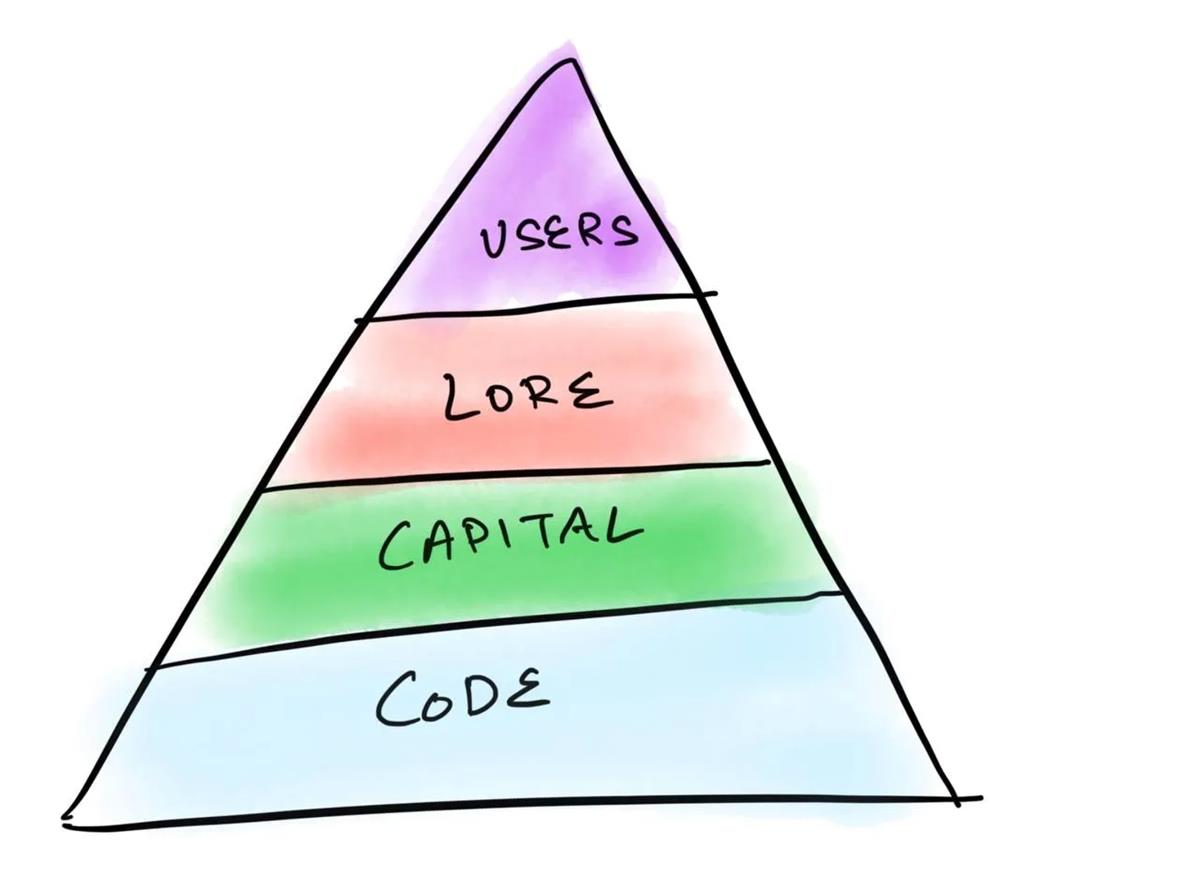

If I were to draw a hierarchy of needs for early protocols and dApps, it would look like the image below. You need developers to:

-

Write code;

-

Invest capital;

-

Attract users.

Without code, we’re just spinning wheels.

Venture capital firms that have existed since the early 2000s heavily emphasize developers. This is because developer count is a precise proxy for potential economic activity on a protocol. Suppose you bought an iPhone because of its camera. Chances are, you’d eventually buy an app to edit photos on the device.

Thus, your initial decision (camera) drives secondary purchases (apps). With each new app, the ecosystem strengthens as the suite of available products expands. The value proposition of buying the device is no longer just the camera—it’s the entire ecosystem opened up to the user.

This shift was also evident in the early internet. People didn’t subscribe to “the internet.” In their minds, they subscribed to a webpage summarizing what happened online. But only when people realized they could send emails, or awkward texts to their school crush, did the open internet truly grow.

Now imagine 20 different internets competing, each with their own listed stocks and app variants with different brands and transaction fees. Consumers would be confused, and the internet wouldn’t be what it is today. This is exactly where we stand with Web3-native protocols.

Value Capture

Protocols need substantial user liquidity to support emerging applications built on top. In the era of rollup upgrades, everyone can pretend to be the next L2. But with each new protocol, we fragment the user base of Web3-native products. A time may come when users won’t know—or care—what chain or stack powers their tools. But we’re not there yet.

During this period, expecting every protocol to generate as much in fees as mature dApps may be misguided. First-gen blockchain dApps were capital-intensive. The next wave may be attention-intensive. There aren’t yet mass-scale Web3 games because we prioritize trading over gameplay. Blockchains are inherently financial infrastructure. So it’s reasonable to assume every user wants to transact.

But this mindset has somewhat hindered industry progress.

All this makes me wonder—what is “value”? Tokens, stocks, gaming items, and other liquid assets always carry premiums. Based on collective hope or fear, these premiums fluctuate. Speculation has driven financial markets for at least eight centuries. I doubt we’ll change this aspect of human behavior anytime soon.

The message for founders is clear. You can make money by pushing narratives, even if protocol fees or usage are weak. Meme tokens are an extreme version of this. Alternatively, you can build a dApp that generates fees with reasonable multiples. Aave and Compound have evolved into platforms with this trait. Both paths require immense effort.

The best founders we’ve seen can drive both narrative and platform usage—relying on only one often leads to disaster. Protocols or applications offering unparalleled core utility may achieve higher adoption due to stickiness. This reflects Peter Thiel’s view that “competition is for losers.” The more crowded a market segment, the lower the chance new entrants capture highly sticky or adopted users. All this considers only user concentration. What about protocol economics?

Anagram’s Joe Eagan offers a great analogy here. The best protocols behave like Amazon. Amazon barely profited for years, but intrinsic network effects paid off long-term. The widest range of sellers meet the largest buyer base on Amazon. Long-term, any “successful” protocol may share similar traits—extremely low fees, hosting the broadest array of applications, enabling users to perform daily functions without going elsewhere. Monetization for such a protocol might come from the richness of data left on-chain.

Such a protocol might launch without a token. It could charge fees in dollars instead of a new native asset. Imagine paying 0.0001 USDC per transaction. Users might get a dollar “top-up” to their wallet after every 10,000 transactions at a local store. But the problem is most base chains can’t do this—their native tokens are essential to their security model, and it’s unclear how such a protocol would profit. Such a protocol could scale exponentially without forcing users to spend heavily every time protocol usage spikes, as happens on today’s Ethereum.

If we believe blockchains are infrastructure for transactions, and all internet activity will become transactions, we may inevitably need low-cost protocols and fixed costs. Or, we might end up with 50 new L2s, each with sky-high valuations because markets love novelty. Markets can support both—perhaps that’s the beauty, balancing utility and speculation.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News