Vitalik: Legitimacy is the scarcest resource in the crypto ecosystem

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik: Legitimacy is the scarcest resource in the crypto ecosystem

This social force is key to helping blockchain networks recover from 51% attacks, and serves as the foundation for a wide range of extremely powerful mechanisms far beyond the blockchain space.

Author: Vitalik Buterin

Translation: Gong Quanyu, Echo

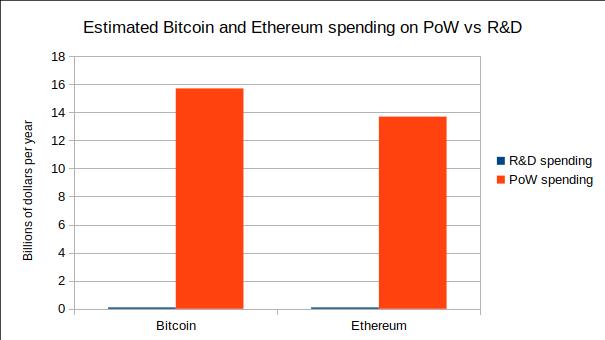

Bitcoin and Ethereum ecosystems spend far more on network security (i.e., PoW mining) than on all other areas combined. Since the beginning of this year, the Bitcoin network has paid miners an average of about $38 million per day in block rewards, plus approximately $5 million daily in transaction fees. The Ethereum network ranks second, paying an average of $19.5 million per day in block rewards and another $18 million per day in transaction fees.

Meanwhile, the Ethereum Foundation's annual budget is only around $30 million, covering research, protocol development, grants, and various other expenses. R&D spending in the Bitcoin ecosystem is likely even lower—around $20 million annually.

Clearly, this spending pattern represents a massive misallocation of resources. Compared to the value provided by research and core protocol development, 20% of the network’s computational power contributes significantly less to the ecosystem. So why not cut 20% of the PoW budget and redirect those funds elsewhere?

The standard answer to this dilemma involves concepts like “public choice theory”: although we can easily identify valuable public goods and make one-time investments into them, establishing a regular, institutionalized mechanism for such decisions risks policy chaos, which isn’t worth it in the long run.

But regardless of the reason, we face an interesting reality: Bitcoin and Ethereum ecosystems as organisms can attract billions of dollars in capital, yet impose strange and hard-to-understand constraints on where that capital goes. The powerful social forces behind this effect are worth understanding—and they’re the same social forces that enabled the Ethereum ecosystem to gather these resources in the first place (while technologically nearly identical ETC did not).

These social forces are key to helping blockchain networks recover from 51% attacks and form the basis of extremely powerful mechanisms extending far beyond the blockchain space. In the following sections, I will name this powerful social force: legitimacy.

I. Tokens Are Owned by Social Contracts

An important example to better understand these forces is the legendary story of Steem and Hive. In early 2020, Justin Sun acquired Steem Inc.—not the same as the Steem blockchain—but the company held about 20% of the STEEM token supply. The community naturally distrusted Justin Sun, so they conducted on-chain voting to formally codify a long-standing "gentlemen's agreement": the tokens held by Steem Inc. were to be held in trust for the common benefit of the blockchain and should not be used for voting.

Using tokens held by exchanges, Justin Sun fought back, gained control over enough nodes, and unilaterally took over the Steem blockchain. With no further options, the community forked the Steem blockchain into a new chain called Hive, copying all STEEM token balances except for those involved in the attack—including Justin Sun’s.

The lesson we can learn from this situation is: companies never truly "own" tokens. If they did, they would have the actual ability to use, enjoy, and abuse those tokens in any way they wanted. But in fact, when the company tried to misuse these tokens in ways disliked by the community, they were successfully stopped. The situation here resembles the model of unreleased Bitcoin and Ethereum rewards: these tokens are ultimately not owned by keys, but by some kind of social contract.

We can apply the same reasoning to many other structures in blockchains. Take the multi-signature private keys of the ENS project, controlled by seven prominent members of the ENS and Ethereum communities. What happens if four of them collude to “upgrade” the registrar to one that transfers all the best domain names to themselves? Within the context of the ENS smart contract system, they technically have full capability to do so, with no built-in challenge. But if they actually attempted to abuse their technical power in this way, everyone knows what would happen: they would be ostracized by the community, the remaining ENS community members would deploy a new ENS contract restoring original domain ownership, and every Ethereum application using ENS would redirect its UI to the new interface.

Legitimacy governs social status games, intellectual discourse, language, property rights, political institutions, national borders—and blockchain consensus works the same way: the only difference between an accepted soft fork and a 51% attack is legitimacy. After a 51% attack, the community can coordinate an additional fork to remove the attacker.

II. What Is Legitimacy?

To understand how legitimacy operates, we need to delve into game theory. There are many situations in life requiring coordinated behavior: if you act in a certain way alone, you may achieve nothing (or worse), but if everyone acts together, desired outcomes can be achieved.

A natural example is driving on the left or right side of the road: it doesn’t really matter which side people drive on, as long as they all drive on the same side. If everyone simultaneously switches sides and most prefer the new arrangement, there’s a net gain. But if only you switch sides—no matter how much you personally prefer it—the outcome for you is quite negative.

Legitimacy is a higher-order acceptance paradigm. A result in a given social context is legitimate if people widely accept it and play their part in enacting it, and they do so because they expect everyone else to do the same.

Legitimacy is a phenomenon that naturally arises in coordination games. If you're not in a coordination game, there's no reason to act based on expectations of others’ behavior, so legitimacy doesn't matter. But as we've seen, coordination games are everywhere in society, making legitimacy highly significant.

These mechanisms are driven by established culture—everyone pays attention to them and acts consistently. Everyone has reason to believe that since others follow these mechanisms, deviating would only create conflict and losses, or at best leave them isolated in a lonely forked ecosystem. If a mechanism successfully achieves this, it possesses legitimacy.

There are many ways legitimacy is achieved. Often, legitimacy emerges because what gains legitimacy psychologically appeals to most people. Of course, human psychological intuitions can be very complex. A complete theory of legitimacy is impossible to list, but we can start with the following aspects:

Legitimacy through force: someone convinces everyone they have sufficient power to enforce their will, and resistance would be extremely difficult. (Similar to moral coercion)

- Continuity-based legitimacy: if something was legitimate at time T, it is presumed legitimate at time T+1.

- Fairness-based legitimacy: something satisfies people's intuitive sense of fairness and thus becomes legitimate.

- Process-based legitimacy: if a process is fair, its output is considered legitimate (e.g., laws passed in democracies are sometimes described this way).

- Performance-based legitimacy: if a process produces results satisfying to people, the process gains legitimacy (e.g., successful dictatorships are sometimes described this way).

- Participation-based legitimacy: if people participate in choosing an outcome, they’re more likely to see it as legitimate. This is similar to fairness but not identical—it depends on the psychological desire to remain consistent with your prior actions.

III. Legitimacy Is a Powerful Social Technology

The state of public goods funding in crypto ecosystems is quite poor. Thousands of billions of dollars flow through these systems, yet public goods critical to their survival receive only tens of millions annually.

There are two responses to this reality. The first is to take pride in these limitations and admire your community’s brave efforts to work within them—even if they’re not particularly effective.

This seems to be the path often taken by the Bitcoin ecosystem:

The self-sacrifice of teams funding core development is admirable in the same way Eliud Kipchoge running a marathon in under two hours is admirable: it’s a display of human perseverance, but it’s not the future of transportation (or in this case, public goods funding).

Just as we have better technologies enabling people to travel 42 kilometers in an hour without special endurance or years of training, we should focus on building better social technologies to fund public goods at the scale we need—as a systemic part of our economic ecosystem, rather than one-off charitable acts.

Now, let’s return to cryptocurrency. The main strength of cryptocurrency (and other digital assets like domains, virtual land, and NFTs) is that it allows communities to pool large amounts of capital without requiring any individual to personally donate it. However, this capital is constrained by the concept of legitimacy: you cannot simply allocate it to a centralized team without undermining the value it represents.

Blockchain ecosystems including Ethereum value freedom and decentralization. Unfortunately, most public goods ecosystems within these blockchains remain authority-driven and centralized. Whether Ethereum, Zcash, or any other major blockchain project, usually one (or at most two or three) entities spend far more than others, leaving independent teams wanting to build public goods with few options. I call this public goods funding model the “Centralized Public Goods Capital Coordinator” (CCCP).

This situation isn’t the fault of the organizations themselves—they typically try their best to support the ecosystem. Rather, the ecosystem’s rules are unfair to them, placing them under unreasonable standards. Any single centralized organization inevitably has blind spots and at least some team members who fail to appreciate certain values. Therefore, creating a more diverse and resilient model of public goods funding—one that reduces pressure on any one organization—is highly valuable.

Fortunately, we already have prototypes of alternatives. The Ethereum application-layer ecosystem already exists, is growing stronger, and has demonstrated public-mindedness. Companies like Gnosis have continuously contributed to Ethereum client development, and various Ethereum DeFi projects have donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to Gitcoin Grants matching pools.

Gitcoin Grants has achieved high legitimacy: its public goods funding mechanism (quadratic funding) has proven neutral and effective in reflecting community priorities and values and filling gaps in existing funding mechanisms.

By directing small portions of treasury funds toward public goods that enable the public-dependent ecosystem, we can strengthen this nascent public investment ecosystem.

There are many ways to support public goods: long-term commitments to supporting Gitcoin Grants matching pools, funding Ethereum client development, or even launching your own donation programs whose scope extends beyond your specific application-layer project.

Of course, the value of community support is limited. If competing projects (or even forks of existing ones) offer users better products, users will flock to and adopt the alternatives.

But these limits vary across contexts. Sometimes community influence is weak; other times, it’s strong. An interesting case study here is Tether versus DAI.

Tether has had many scandals, yet traders continue to use it for holding and transferring dollars. Despite DAI’s benefits of decentralization and transparency, at least in the eyes of traders, it hasn’t managed to capture most of Tether’s market share. But DAI excels in applications: Augur uses DAI, xDai uses DAI, Pool Together uses DAI, and the list grows. How many dApps use USDT? Far fewer.

Thus, while the influence of community-driven legitimacy isn’t infinite, there’s still substantial leverage—enough to encourage projects to dedicate at least a few percent of their budgets to broader ecosystem support.

IV. NFTs: Supporting Public Goods Beyond Ethereum

The concept of legitimacy through public support enables value generated outside Ethereum to fund public goods—value extending far beyond the Ethereum ecosystem. NFTs represent a significant and direct opportunity that could greatly assist many types of public goods, especially creative ones, at least partially solving their long-standing and systemic funding shortages.

But it could also be a missed opportunity: when Elon Musk sells his tweet for $1 million, there’s little social value—and as far as we know, the money goes entirely to him (admirably, he eventually decided not to sell). If NFTs merely become casinos enriching already wealthy celebrities, the outcome won’t be very interesting.

Fortunately, we can help shape the outcome. Which NFTs people find attractive and which they don’t is a question of legitimacy: if everyone agrees one NFT is interesting and another is worthless, people will prefer buying the first—not just for bragging rights and personal pride, but also because others think similarly, increasing its potential resale value. If we can steer the concept of NFT legitimacy in the right direction, there’s a real chance to establish solid funding channels for artists, charities, and other organizations.

Here are two potential ideas:

First, certain institutions (or even DAOs) could mint “blessing” NFTs, conditional on a portion of proceeds going to charity, ensuring multiple groups benefit. These blessings could even come with official categorizations: is the NFT dedicated to global poverty alleviation, scientific research, creative arts, local journalism, open-source software development, empowering marginalized communities, or something else?

Second, we can collaborate with social media platforms to make NFTs more visible on user profiles, allowing buyers to showcase their committed values. This could be combined with the previous point to bias users toward NFTs that support meaningful social causes.

V. Conclusion

In summary, the concept of legitimacy is extremely powerful, appearing in any environment involving coordination—especially online, where coordination is ubiquitous. Legitimacy forms in multiple ways: force, continuity, fairness, process, performance, and participation are all important factors.

Cryptocurrencies are powerful because they allow us to mobilize large amounts of capital through collective economic will—capital that initially belongs to no single person. Instead, these pools of capital are directly governed by the concept of legitimacy.

Starting public goods funding via token issuance at the base layer is too risky. Fortunately, Ethereum has a rich application-layer ecosystem where we have greater flexibility. Partly because we have opportunities not only to influence existing projects but also to shape new ones yet to emerge.

The Ethereum ecosystem cares about mechanism design and social innovation. Its own public goods funding challenges provide a great starting point. But this extends far beyond Ethereum itself. NFTs are an example of a large capital pool dependent on the concept of legitimacy.

The NFT industry could be a huge boon for artists, charities, and other public goods providers—far beyond our virtual world. But this outcome isn’t predetermined; it depends on active collaboration and support.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News