Exploring NFT-native Solutions: Infrastructure and Opportunities for NFT MEV

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Exploring NFT-native Solutions: Infrastructure and Opportunities for NFT MEV

The market structure of NFTs is vastly different from that of FTs, and so is NFT MEV.

Written by: Alana Levin, Variant

Compiled by: TechFlow

TL;DR

NFT market structure differs significantly from FT market structure. In NFT markets, capital formation events (mints) are more frequent, secondary trading volume is lower, there are challenges around bid-side liquidity, and many order books operate off-chain.

Due to these differences, NFT MEV also diverges. Specifically, there are fewer arbitrage opportunities, while more MEV is extracted during mints. We also identify several forms of MEV unique to NFT markets: scanning and relisting floor assets into bidding walls (artificially creating high-volume arbitrage conditions), trait sniping, and extracting value from inactive listings.

Treating DeFi markets as more mature and using them as a proxy for where NFTs could go helps clarify existing gaps and areas of infrastructure that can address current challenges. These opportunities include MEV-aware minting solutions, more open pricing data, dynamic on-chain order books, experimentation with new auction models, and additional communication channels for traders.

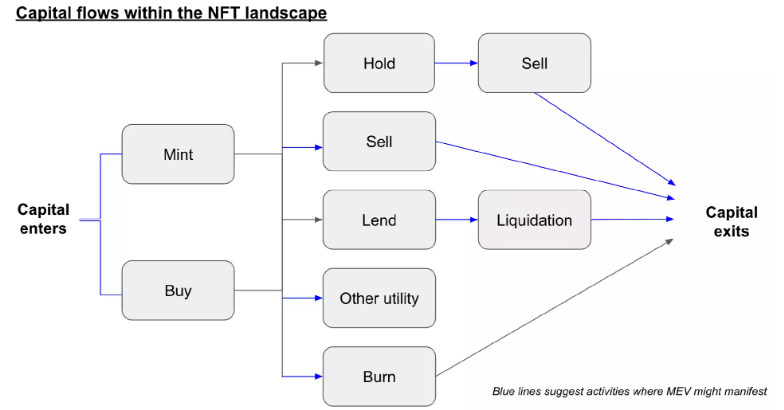

Currently, value circulation around NFTs typically occurs at initial mint or when traded or borrowed in secondary markets. Both forms of value transfer may be subject to MEV—economic inefficiencies extracted from users through on-chain transactions. How this MEV is handled could influence the business models and beneficiaries of market activity—from traders to marketplaces, wallets, and creators.

However, MEV in the NFT space appears to be an under-discussed topic. I believe this is because NFT market structures differ fundamentally from those in DeFi. Critically, these structural differences—including more primary-market activity, smaller token supplies, and thinner secondary liquidity—affect how value flows.

This article aims to outline emerging MEV opportunities in NFT markets, how shifting market dynamics impact these opportunities, and what kinds of infrastructure could be built to account for them.

Current State of the NFT Market

Understanding the current structure of the NFT market is a useful foundation for identifying how MEV manifests within it. The process begins with users minting NFTs, which I refer to as capital formation events—analogous to airdrops or launches in fungible token markets (the creation of new assets on-chain). However, there are at least three key differences between fungible and non-fungible markets:

In non-fungible markets, capital formation events are far more frequent. This is because each new NFT mint is often seen as creating a new artwork or collectible, each with uniqueness and scarcity. As such, creators and collectors tend to produce and acquire as many NFTs as possible.

In non-fungible markets, the order of minting may matter, as serial numbers can carry financial value—such as rarity attributes or identity signals.

Non-fungible collections typically have much smaller supplies. A collection might only mint 10,000 NFTs, whereas fungible tokens often launch with supplies of one billion or more. This impacts secondary market liquidity.

When users decide to no longer hold their NFTs, they can sell them on marketplaces (such as OpenSea, Blur, or many platforms supported by Reservoir). These orders are typically placed on off-chain order books, where they remain pending until fulfilled or canceled. For these off-chain books, actual on-chain activity has several touchpoints: first listing (setting approval), canceling, and fulfilling. Price changes require seller signatures but not additional gas fees. Some order books run fully on-chain, such as Zora and Sudoswap.

Beyond primary and secondary trading, it’s worth noting an emerging utility market for NFTs. On-chain utility may involve staking NFTs for rewards, delegating to qualify for upcoming airdrops, or burning (destroying) NFTs when used as in-game assets. But context matters: in February, primary and secondary market volumes approached $2 billion, while NFT lending totaled only a few hundred million dollars. Utility markets beyond lending are even less mature. Thus, minting and trading will remain the focus here.

What Is NFT MEV?

I define MEV as any form of inefficiency within a market that causes value leakage from transaction initiators (users, wallets, applications) down the stack (to searchers, block builders, validators). This is a broad definition, but helpful when considering different value capture and/or redistribution opportunities. Common forms of MEV include arbitrage, sandwich attacks, and liquidations.

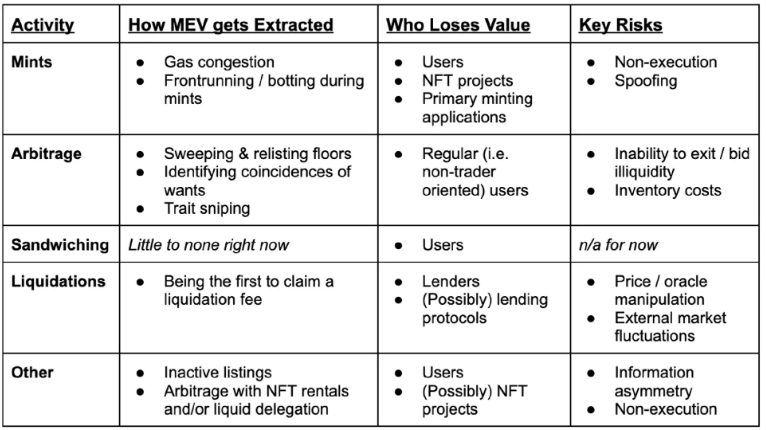

Arbitrage

Arbitrage and sandwich attacks typically require high trading volume and deep liquidity, as spreads are often narrow and arbitrageurs want fast entry and exit. NFT markets usually lack these conditions. Moreover, liquidity challenges exist: often, there isn’t a ready buyer on the other side of a listing. Even if someone spots an arbitrage opportunity, exiting (relisting and reselling) may be risky.

Some NFT-native forms of arbitrage—and associated risks—are as follows:

Scanning and relisting floor-priced NFTs at higher prices. Many traders claim profits by exploiting potential bid walls above floor price. Here, traders almost artificially create the high-volume conditions needed for arbitrage. Key risks include high capital costs and inventory exposure.

Finding coincidences not yet recognized as equivalent demand. For example, someone lists their CryptoPunk with red/blue glasses for 1 ETH, while another bids 2 ETH for any CryptoPunk with red/blue glasses. A searcher can step in, use Seaport’s MATCH function to fulfill both orders, and pocket the difference as a tip (reward). This seems like a low-risk arbitrage, though infrequent. The main risk here is non-execution.

Trait sniping is a uniquely “non-fungible” form of arbitrage. If a searcher sees an NFT with a specific trait trading at price X, but knows others with the same trait trade at X+Y, they can buy and relist at a higher price. MEV is captured if the searcher pays high gas to prioritize their bid. The key risk is exit: there may be no waiting bid on the other side of their listing. Thus, the searcher bears inventory risk over an unknown period and faces volatility in trait pricing.

Sandwich Attacks

Currently, sandwich attacks appear rare in NFT markets. Partly because most NFTs don’t dynamically reprice when available supply changes.

In fungible markets, large orders affect pricing. Buying 10% of floor-priced NFTs doesn’t directly change the price of other floor NFTs.

NFTs are usually priced individually, not aggregated. Notably, some dynamic pricing infrastructure (like NFT AMMs—“Uniswap for NFTs”—e.g., Sudoswap) is emerging. Sudoswap addresses NFT liquidity by ensuring at least some bids exist for pooled NFTs. The trade-off? Dynamic, automated pricing also expands the surface area for sandwich attacks.

Liquidation MEV

Another common form of MEV exists in lending markets: “liquidation MEV,” where searchers profit by being the first to discover and claim liquidation fees. More lending protocols are being built on-chain (e.g., housing liquidation engines directly on protocols like Seaport), featuring Dutch auctions with declining prices that trigger when collateral values fall below thresholds. I expect a cohort of searchers will specialize in manipulating floor prices or certain NFT collateral values to pre-position or control when NFTs get liquidated.

Other Types of NFT MEV

May include:

Congestion during mints. Popular mints can lead users to pay millions in gas fees—value created by NFT projects but ultimately extracted by validators.

Bot usage during mints. Searchers can detect the first mint transaction in the mempool, inspect remaining supply, and front-run part or all of the remaining mint.

Inadvertently leaving untraded orders (commonly called inactive listings). Since canceling incurs gas fees, users sometimes simply transfer the NFT to a new wallet to end the sale. Tricky: technically, the original listing remains active—if the NFT is transferred back, the listing reappears. By then, the floor price may have risen above the original ask. A savvy third party can front-run the undervalued NFT. MEV arises when searchers bribe validators with high gas to prioritize their bid on such listings.

Arbitrage related to NFT leasing. We’re seeing trends to decouple NFT rights/utilities from the asset itself—essentially, an Airbnb for NFTs: owning the asset (“house”) but letting others pay to temporarily use benefits normally reserved for owners. Such fluid delegation is especially useful for airdrop-related arbitrage—buying rights to many NFTs (rather than the NFTs themselves) to qualify for airdrops requires less capital, limits floor-price spikes, and offers chances to capture significant portions of airdrop supplies. If we start seeing stricter airdrop eligibility rules (as already observed in fungible markets), holders may possess asymmetric information about the likely size of claimable airdrops tied to their NFTs.

Finally, there may be more forms of NFT MEV not mentioned here—counterfeiting, inefficiencies tied to burn-and-redeem functions, pre-bidding mints, among others. This list is meant to be creative and inspirational, hoping to spark ideas or projects focused on reducing or capturing NFT MEV opportunities.

Infrastructure Opportunities

Based on the current market state and where MEV particularly exists, the following could present interesting opportunities to build NFT-native infrastructure.

MEV-aware minting solutions. Auctions built specifically for NFTs could help projects capture more of the value they create: allowing users to bid for mint access and sequence could offer a way to enable price discrimination while mitigating high gas prices. If ordering happens off-chain or pre-mint, projects could spread mints over days or choose times with less on-chain congestion.

Enhanced pricing infrastructure. This could take various forms—better data showing how traits are priced (e.g., helping searchers spot trait-sniping opportunities), dynamic pricing mechanisms (like Sudoswap) that help aggregate rather than individually price NFTs, continuous auctions to improve price discovery, or other models.

Infrastructure to reduce exit (liquidity) risk. I generally believe NFT pricing is difficult, so fewer people are willing to bid. Bargaining mechanisms might help. If a user lists their NFT at 2 ETH and a buyer offers 1 ETH, there may be a middle ground. Negotiation channels could increase overall liquidity and improve understanding of NFT valuation. Indeed, significant overlap may exist between this category and the one above (pricing infrastructure).

More efficient fulfillment protocols and tools. As orders grow more complex (e.g., sellers listing multiple NFTs per order) and more active traders or market makers enter the space, finding efficient ways to match or fill orders improves user experience. Seaport and Reservoir are excellent examples of complementary infrastructure in this category: both facilitate cross-market liquidity sharing, enabling more effective discovery and matching across diverse environments. Relatedly, the surface area for identifying demand coincidences will continue expanding, offering opportunities to build preference-aware matching solutions specialized in partial fills across order networks. I also envision better methods catering to different trader types: professional traders may prefer near-instant settlement, while retail-oriented users might accept bids accepted at time X being technically settled/transferred hours later when gas costs are lower.

Conclusion

Looking ahead, I’m confident we’ll see more evolution around NFTs. Currently, most NFTs are highly heterogeneous, making them hard to substitute. NFTs sharing traits or belonging to a floor-price group are closer to substitutes, but consumer preferences may still vary.

By contrast, consider NFTs as venue passes for a golf tournament—here, heterogeneity exists (e.g., due to date), causing preference differences, but overall they act as close substitutes since consumers treat tickets interchangeably within a given day (assuming equal access rights).

As the spectrum evolves—with NFTs representing everything from on-chain art to tickets, membership links, IP licenses, property deeds—I expect we’ll see more MEV emerge.

Overall, it feels we’re still in the early stages of NFTs.

I enjoy thinking about NFTs because I believe they are an excellent way to bring exogenous capital into the crypto ecosystem, and I think the design space is completely open. But in any market’s early stage, inefficiencies inevitably exist.

I hope exploring how MEV manifests across the market—and what opportunities this reveals for building better user experiences—will help pave the way toward broader adoption.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News