SharkTeam: Web3 Security Report H1 2024

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

SharkTeam: Web3 Security Report H1 2024

In the first half of 2024, losses due to hacking attacks, phishing attacks, and rug pull scams amounted to approximately $1.492 billion.

Author: SharkTeam

In the first half of 2024, losses caused by hacking attacks, phishing attacks, and Rugpull scams amounted to approximately $1.492 billion, representing a year-on-year increase of 116.23% compared to around $690 million in the first half of 2023. This report aims to analyze and summarize the global Web3 industry's security landscape, major incidents, and key regulatory developments in the cryptocurrency sector during the first half of 2024. We hope this report provides valuable insights and perspectives for readers and contributes to promoting the safe and healthy development of Web3.

I. Overview

In the first half of 2024, losses caused by hacking attacks, phishing attacks, and Rugpull scams amounted to approximately $1.492 billion, representing a year-on-year increase of 116.23% compared to around $690 million in the first half of 2023. This report aims to analyze and summarize the global Web3 industry's security landscape, major incidents, and key regulatory developments in the cryptocurrency sector during the first half of 2024. We hope this report provides valuable insights and perspectives for readers and contributes to promoting the safe and healthy development of Web3.

II. Trend Analysis

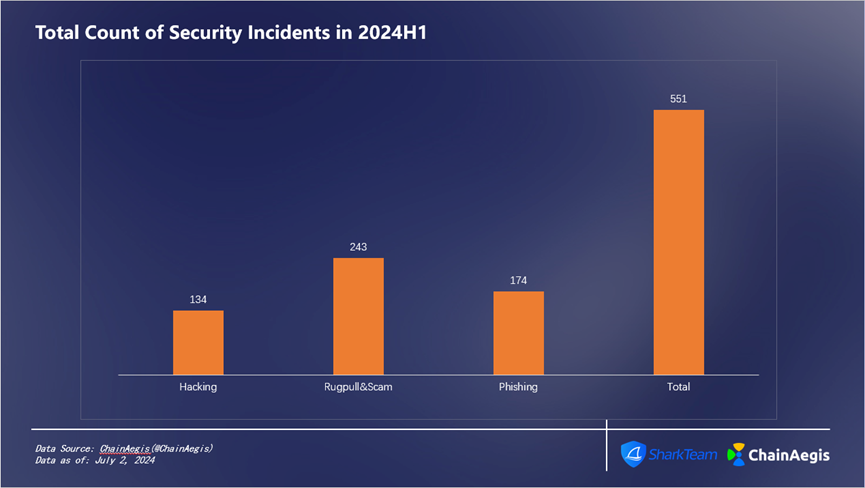

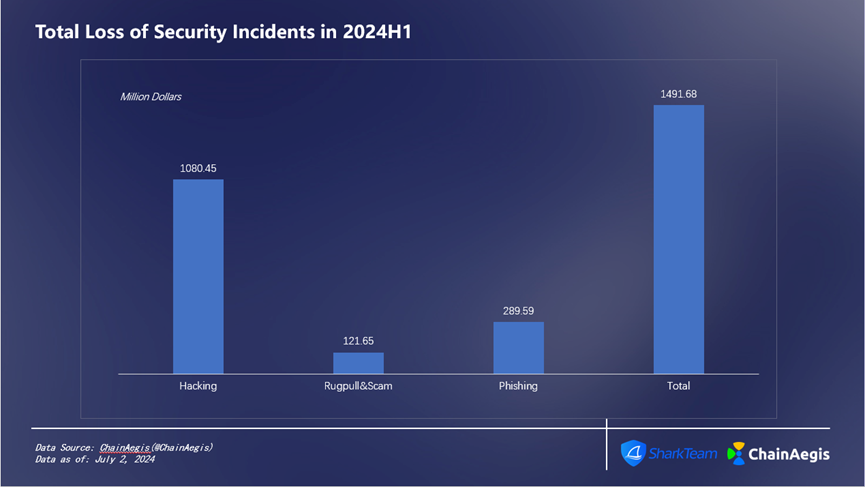

According to data from ChainAegis, SharkTeam’s on-chain intelligent risk identification platform, there were 551 security incidents in the Web3 domain in the first half of 2024 (Figure 1), with cumulative losses exceeding $1.492 billion (Figure 2). Compared to the same period last year, the number of security incidents increased by 25.51%, while the total loss amount rose by 116.23%.

Figure 1 Total Count of Security Incidents in 2024H1

Figure 2 Total Loss of Security Incidents in 2024H1

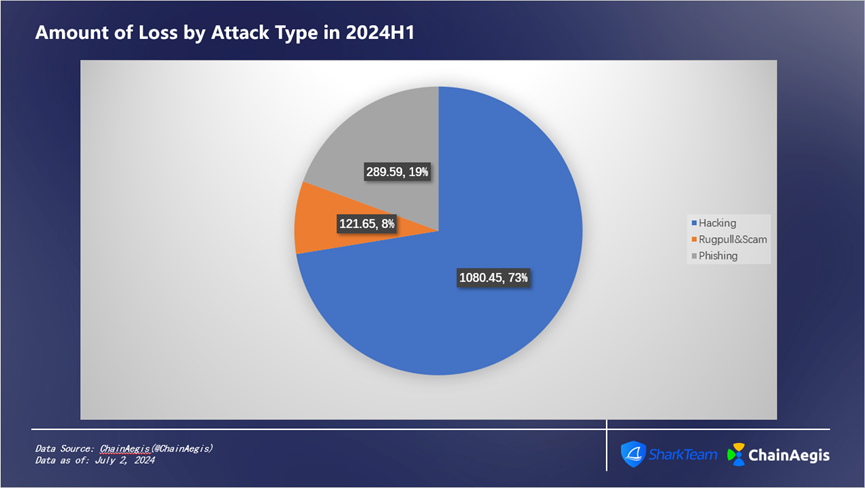

There were 134 hacking-related security incidents in the first half of 2024, an increase of 103.03% compared to H1 2023, resulting in losses of $1.08 billion—accounting for 73% of total losses (Figure 3)—a 147.71% increase compared to $436 million in H1 2023.

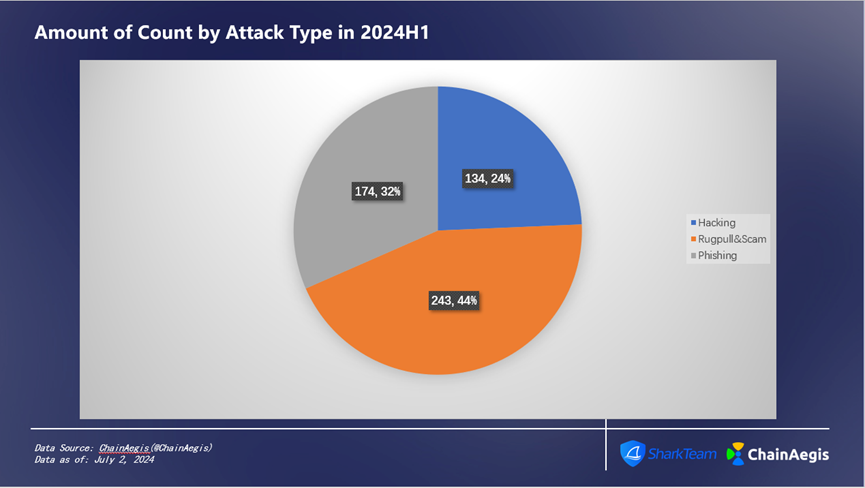

Rug Pulls occurred 243 times in the first half, a surge of 331.15% compared to 61 incidents in H1 2023, with financial losses increasing by 258.82% to $122 million, accounting for 8% of total H1 losses.

Phishing attacks totaled 174 incidents in H1, up 40.32% year-on-year, causing losses as high as $290 million, representing 19% of total losses.

Figure 3 Amount of Loss by Attack Type in 2024H1

Figure 4 Amount of Count by Attack Type in 2024H1

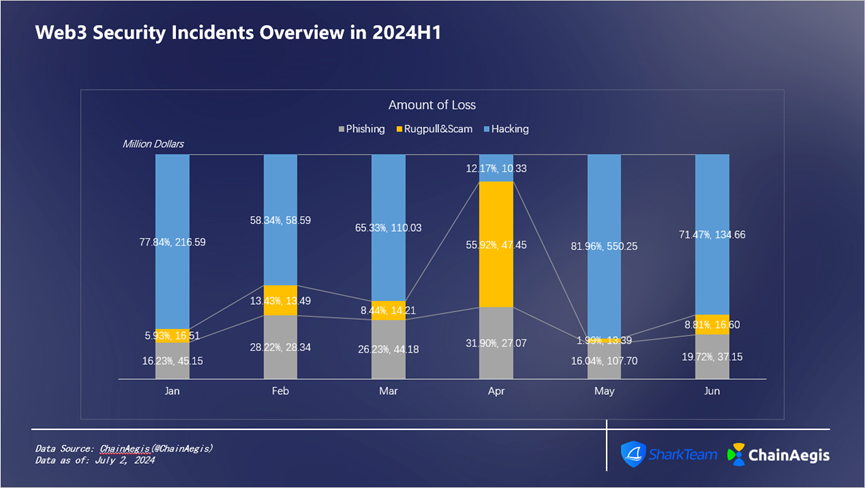

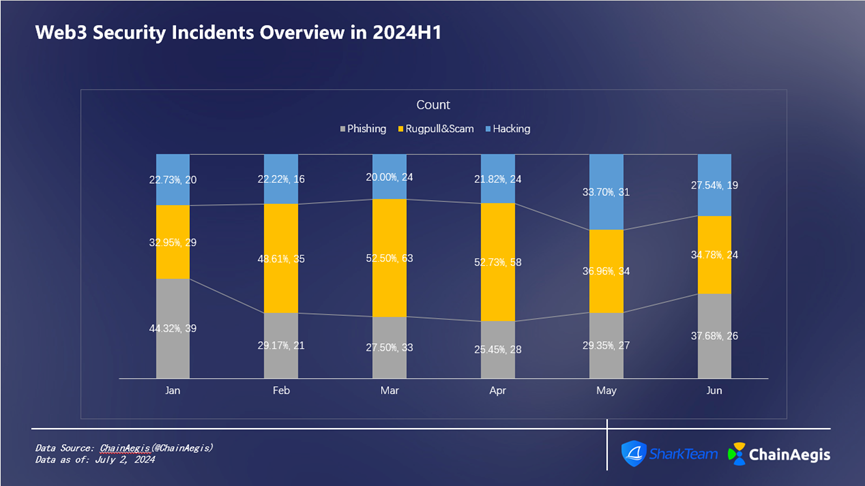

On a monthly basis in H1 (Figures 5 and 6), May saw the highest losses—approximately $643 million—with 92 security incidents, including 31 hacks, 34 Rugpulls, and 27 phishing attacks.

Figure 5 Web3 Security Incidents Loss Overview in 2024H1

Figure 6 Web3 Security Incidents Count Overview in 2024H1

2.1 Hacking Attacks

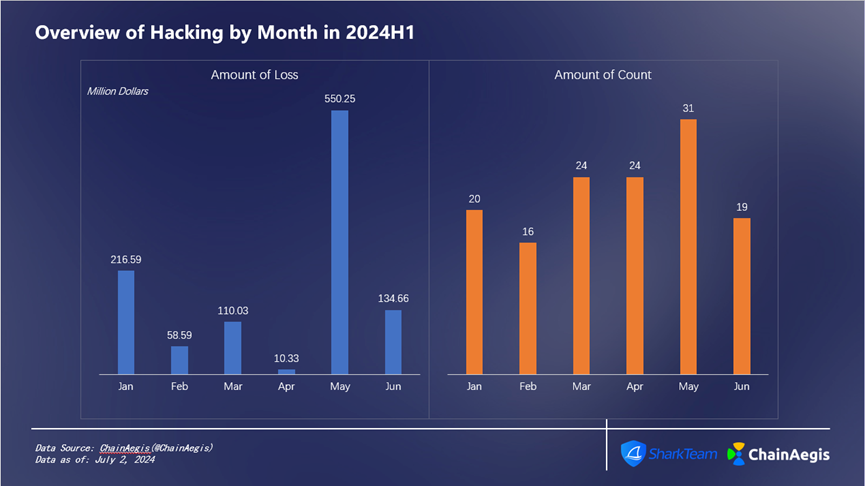

There were 134 hacking incidents in the first half of the year, totaling $1.08 billion in losses. (See detailed data in Figure 7)

On May 21, 2024, the Gala Games protocol on Ethereum was hacked, resulting in a loss of $21.8 million. After the attack, the project team took immediate action, blacklisted the hacker’s address, and froze permissions related to further token sales.

On May 31, 2024, DMM Bitcoin Exchange—a subsidiary of Japanese securities company DMM.com—experienced unauthorized outflows of a large amount of Bitcoin, amounting to approximately ¥48 billion (about $300 million). This marks the seventh-largest crypto theft in history and the largest since December 2022.

Figure 7 Overview of Hacking by Month in 2024H1

2.2 Rugpull & Scams

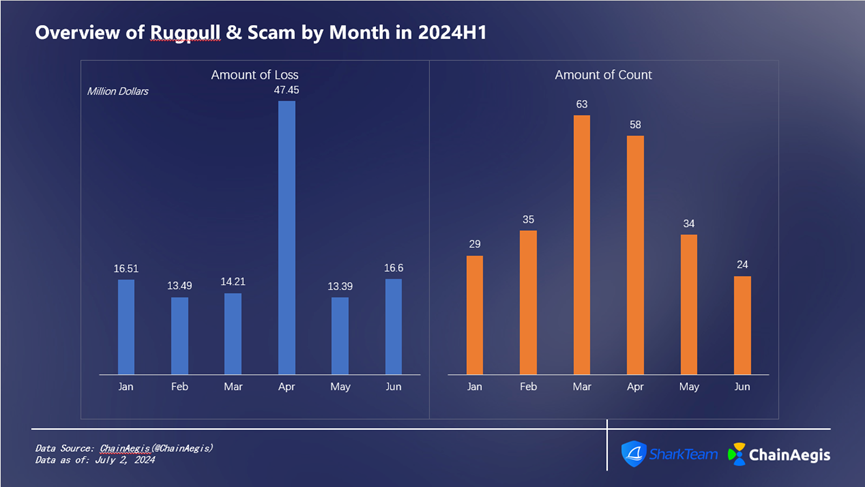

As shown below (Figure 8), Rugpull & Scam events peaked in March at 63 incidents and reached their lowest frequency in June with only 24. April saw the highest financial loss—approximately $47.45 million—with the ZKasino project abandonment being the primary reason for the high losses that month.

Figure 8 Overview of Rugpull&Scam by Month in 2024H1

2.3 Phishing Attacks

As shown in Figure 9, phishing attacks were most frequent in January, occurring 39 times with losses of about $44.15 million. February had the fewest incidents (21) and losses of about $28.34 million. Although May saw only 27 phishing incidents, it recorded the highest monthly loss in H1—$108 million. On May 3, 2024, one user lost 1,155 WBTC (worth over $70 million) due to an address-poisoning phishing attack.

Figure 9 Overview of Phishing by Month in 2024H1

III. Case Studies

3.1 Sonne Finance Attack Analysis

On May 15, 2024, Sonne Finance suffered an attack, resulting in losses exceeding $20 million.

Attacker: 0xae4a7cde7c99fb98b0d5fa414aa40f0300531f43

Attack transaction:

0x9312ae377d7ebdf3c7c3a86f80514878deb5df51aad38b6191d55db53e42b7f0

Attack process:

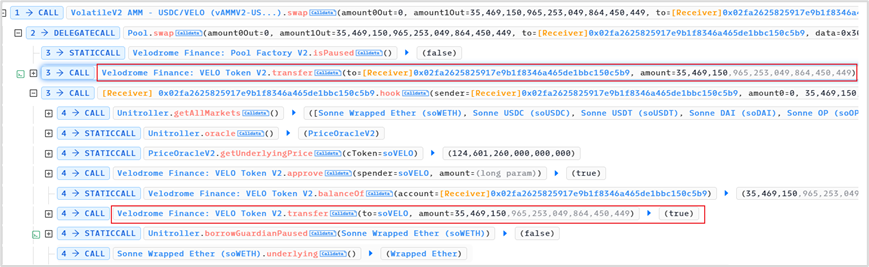

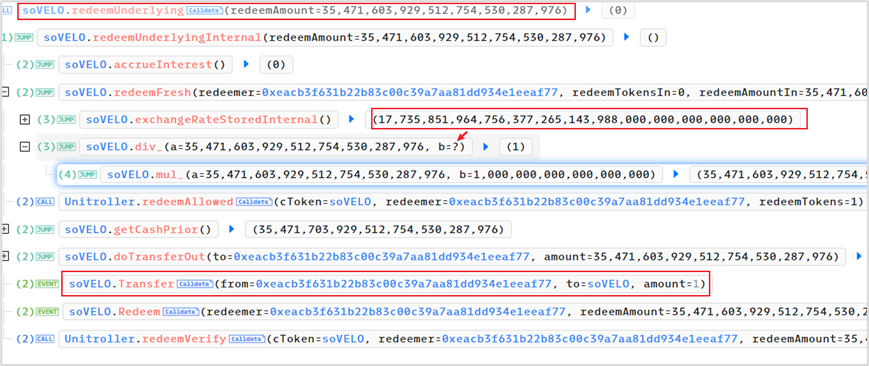

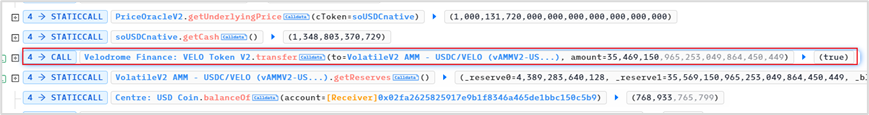

1. Flash loaned 35,569,150 VELO and transferred these VELO tokens directly to the soVELO contract.

Because this was a direct transfer (donation), no new soVELO tokens were minted. As a result, the totalCash in the soVELO contract increased by 35,569,150 VELO, but the totalSupply of soVELO remained unchanged.

2. The attacker created a new contract (0xa16388a6210545b27f669d5189648c1722300b8b) and launched the attack through this new contract. The steps were as follows:

(1) Transferred 2 soVELO into the new contract

(2) Declared soWETH and soVELO as collateral

(3) Borrowed 265,842,857,910,985,546,929 WETH from soWETH

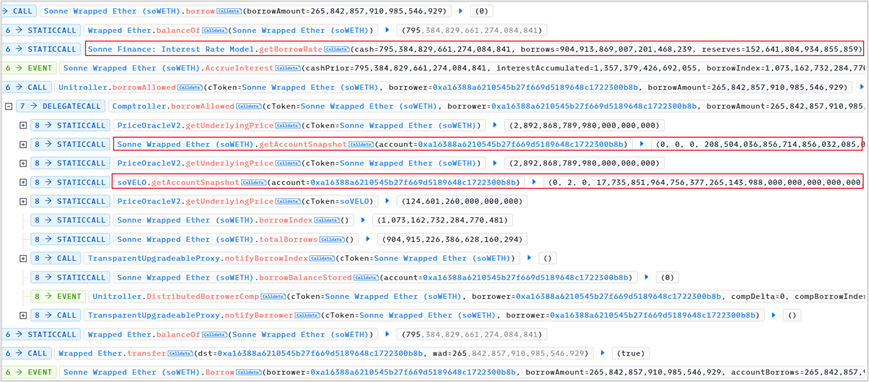

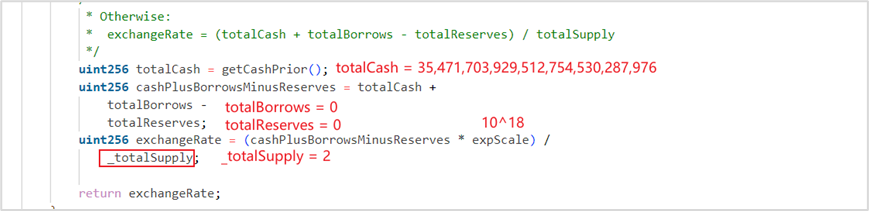

From the execution of the above borrow function, based on the return value of the getAccountSnapshot function, we observe:

For the soWETH contract: balance = 0, borrow amount = 0, exchangeRate = 208,504,036,856,714,856,032,085,073

For the soVELO contract: balance = 2 (i.e., 2 wei of soVELO pledged), borrow amount = 0, exchangeRate = 17,735,851,964,756,377,265,143,988,000,000,000,000,000,000

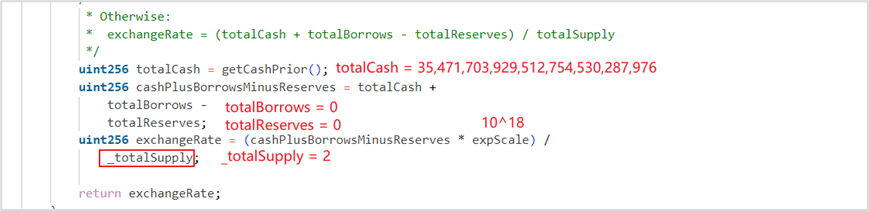

The exchangeRate is calculated as follows:

Pledging 1 wei of soVELO allows borrowing up to 17,735,851,964,756,377,265,143,988 VELO. To borrow 265,842,857,910,985,546,929 WETH, at least 265,842,857,910,985,546,929 soWETH would be required.

soWETH price: soWETHPrice = 2,892,868,789,980,000,000,000

soVELO price: soVELOPrice = 124,601,260,000,000,000

The amount of WETH that can be borrowed per 1 wei of soVELO collateral is:

1 * exchangeRate * soVELOPrice / soWETHPrice = 763,916,258,364,900,996,923

Approximately 763 WETH. Thus, just 1 wei of soVELO is sufficient to support this loan.

To borrow 265,842,857,910,985,546,929 WETH (~265 WETH), the minimum required soVELO collateral is:

265,842,857,910,985,546,929 * soWETHPrice / soVELOPrice / exchangeRate = 0.348

That is, only 1 wei of soVELO collateral is needed.

In practice, although 2 wei of soVELO were pledged, only 1 wei was used in the borrowing process.

(4) Redeemed the target asset: 35,471,603,929,512,754,530,287,976 VELO

exchangeRate = 17,735,851,964,756,377,265,143,988,000,000,000,000,000,000

The required soVELO collateral to redeem 35,471,603,929,512,754,530,287,976 VELO is:

35,471,603,929,512,754,530,287,976 * 1e18 / exchangeRate = 1.99999436

Due to truncation (not rounding) in the calculation, the actual required collateral is rounded down to 1 wei of soVELO.

The actual collateral was 2 wei of soVELO: 1 wei used for borrowing 265 WETH, and the remaining 1 wei used to redeem 35M VELO.

(5) Transferred the borrowed 265 WETH and redeemed 35M VELO to the attacker’s contract

3. Repeated steps 2–4 three more times (four times total) using newly created contracts.

4. Finally, repaid the flash loan.

5. Vulnerability Analysis

The above attack exploited two vulnerabilities:

(1) Donation attack: Directly transferring (donating) VELO tokens to the soVELO contract altered the exchangeRate, allowing the attacker to borrow ~265 WETH with only 1 wei of soVELO collateral.

(2) Precision loss issue: Exploiting computational precision loss combined with the manipulated exchangeRate, the attacker could redeem 35M VELO while pledging only 1 wei of soVELO.

6. Security Recommendations

Based on this incident, the following best practices should be followed during development:

(1) Maintain logical completeness and rigor throughout design and implementation—especially regarding deposits, staking, state updates, and arithmetic operations involving division/multiplication—to minimize exploitable edge cases.

(2) Conduct professional third-party smart contract audits before deployment.

3.2 Common Web3 Phishing Methods and Security Recommendations

Web3 phishing is a common attack vector targeting users by stealing authorizations or signatures, or tricking them into unintended actions, ultimately aiming to steal cryptocurrency assets from wallets.

In recent years, Web3 phishing incidents have surged, giving rise to a black-market ecosystem known as "Drainer as a Service" (DaaS), highlighting increasingly severe security challenges.

This section presents a systematic analysis of common Web3 phishing techniques and offers security recommendations to help users better identify scams and protect their digital assets.

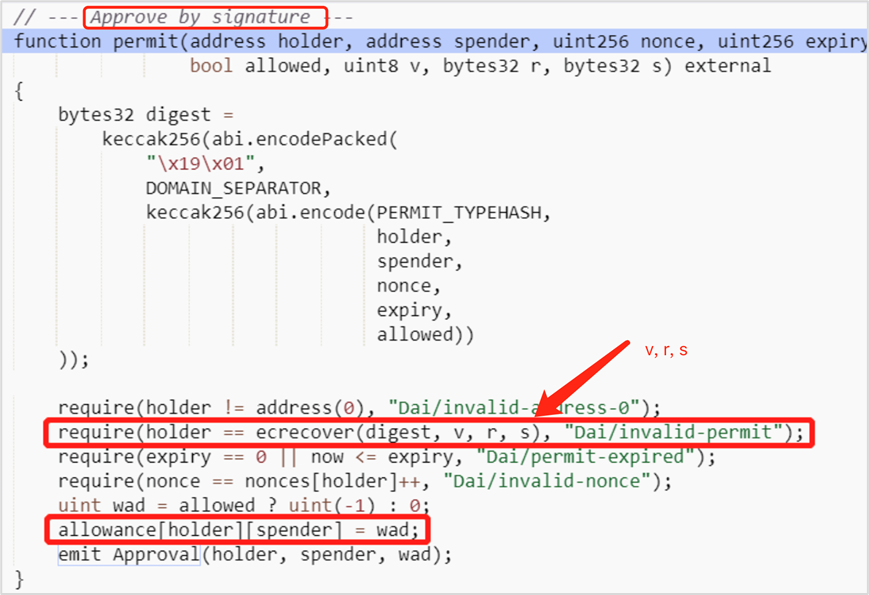

Permit Off-Chain Signature Phishing

Permit is an extension of the ERC-20 standard enabling off-chain authorization—essentially allowing you to sign approval for another address to spend your tokens. The mechanism works as follows: You sign a message authorizing a specific address; that address then uses your signature in a permit() call on-chain to gain spending rights and transfer your assets. Permit-based phishing typically involves three steps:

(1) Attackers create fake links or websites to lure victims into signing messages (off-chain, no gas fee).

(2) Attackers call the permit() function to complete authorization.

(3) Attackers call transferFrom() to drain victim’s funds.

Note the difference between transfer and transferFrom: When directly sending ERC-20 tokens, transfer() is used. transferFrom() is used when a third party transfers tokens on your behalf after receiving approval.

This signature is off-chain and gasless. The attacker performs the permit and transferFrom calls on-chain, so victims won’t see an explicit approval record in their transaction history—only the final fund transfer. These signatures are usually one-time use and do not pose ongoing risks.

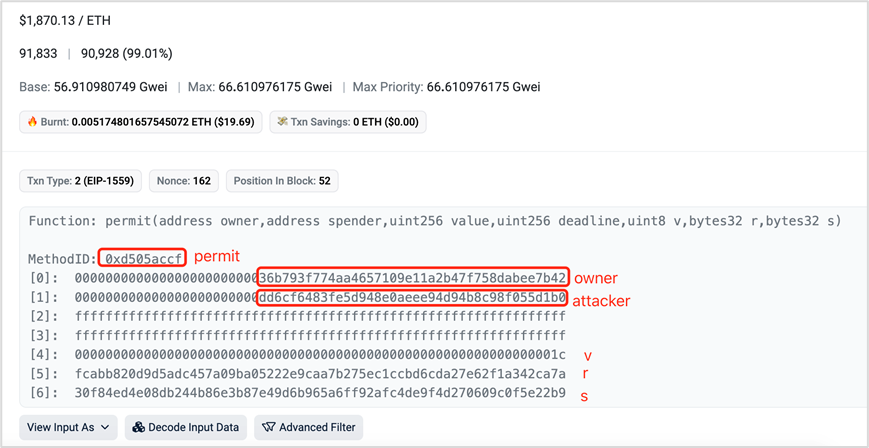

Permit2 Off-Chain Signature Phishing

Permit2 is a token approval contract introduced by Uniswap in late 2022 to improve user experience. It enables shared and managed token approvals across different DApps, offering a more unified authorization system and reducing transaction costs.

Before Permit2, swapping tokens on Uniswap required two steps: Approve + Swap—two separate transactions and gas fees. With Permit2, users grant full allowance once to Uniswap’s Permit2 contract and then perform swaps via off-chain signatures.

While improving usability, Permit2 has also become a target for phishing. Similar to regular Permit phishing, Permit2 attacks involve four steps:

(1) Prerequisite: The victim must have previously used Uniswap and granted token allowances to the Permit2 contract (which defaults to approving the full token balance).

(2) Attackers create fake links or pages to trick users into signing, collecting necessary signature data similar to Permit phishing.

(3) Attackers call the permit() function on the Permit2 contract to authorize access.

(4) Attackers call transferFrom() on Permit2 to drain assets.

The recipient addresses often include multiple parties: one large withdrawal going to the direct attacker, and others to DaaS providers (e.g., PinkDrainer, InfernoDrainer, AngelDrainer).

eth_sign Blind Signing Phishing

eth_sign is an open-ended signing method allowing signatures on arbitrary hashes. Attackers craft malicious payloads (e.g., token transfers, contract calls, approvals) and trick users into signing via eth_sign to execute attacks.

MetaMask shows warnings for eth_sign, while wallets like imToken and OneKey have disabled it or added alerts. We recommend all wallet developers disable this method to prevent exploitation due to lack of user awareness or technical knowledge.

personal_sign/signTypedData On-Chain Signing Phishing

personal_sign and signTypedData are commonly used signing methods. Users must carefully verify the signer, domain, and content before confirming. If used as “blind signing” where plaintext is hidden, users are vulnerable to phishing.

Approval Phishing

Attackers create malicious websites or compromise official sites to trick users into approving setApprovalForAll, Approve, Increase Approval, or Increase Allowance actions, thereby gaining control over user assets.

Address Poisoning Phishing

Address poisoning is a prevalent phishing technique. Attackers monitor on-chain transactions and generate fake addresses mimicking legitimate counterparties—typically matching the first 4–6 and last 4–6 characters. They send small amounts or worthless tokens to the victim’s address from these spoofed addresses.

If the victim later copies a counterparty address from transaction history without careful verification, they may accidentally send funds to the malicious address.

On May 3, 2024, a user fell victim to this method, losing 1,155 WBTC valued at over $70 million.

Legitimate address: 0xd9A1b0B1e1aE382DbDc898Ea68012FfcB2853a91

Malicious address: 0xd9A1C3788D81257612E2581A6ea0aDa244853a91

Normal transaction:

https://etherscan.io/tx/0xb18ab131d251f7429c56a2ae2b1b75ce104fe9e83315a0c71ccf2b20267683ac

Address poisoning:

https://etherscan.io/tx/0x87c6e5d56fea35315ba283de8b6422ad390b6b9d8d399d9b93a9051a3e11bf73

Erroneous transfer:

https://etherscan.io/tx/0x3374abc5a9c766ba709651399b6e6162de97ca986abc23f423a9d893c8f5f570

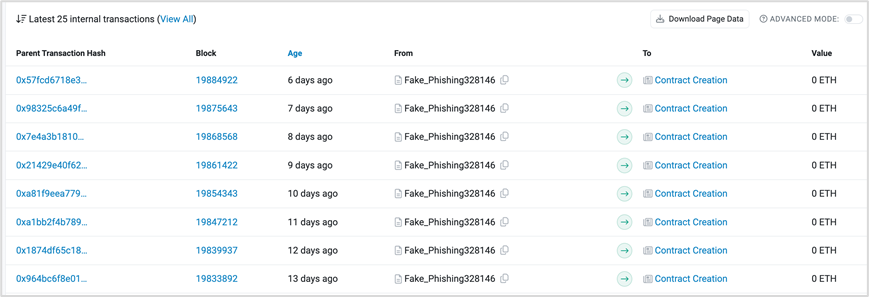

More Stealthy Phishing: Using CREATE2 to Bypass Detection

Wallets and security plugins now offer visual warnings for known phishing patterns and blacklist checks, improving user awareness. However, attackers continue developing stealthier methods. One common recent tactic is abusing CREATE2 to bypass blacklist detection.

CREATE2 is an opcode introduced during Ethereum’s Constantinople upgrade, allowing users to predictably deploy contracts at precomputed addresses. Unlike CREATE, which uses sender and nonce, CREATE2 enables address calculation before deployment. While powerful for developers, it introduces new risks.

Attackers abuse CREATE2 to generate fresh contract addresses with no prior malicious history, evading blacklist detection. When victims sign seemingly harmless transactions, attackers deploy malicious code at the precomputed address and drain funds—an irreversible process.

Characteristics of this attack:

- Enables predictable contract creation, letting attackers trick users into granting permissions before deployment.

- Since the contract doesn’t exist at authorization time, the address appears clean, bypassing historical blacklists and making detection extremely difficult.

Example of CREATE2-based phishing:

https://etherscan.io/tx/0x83f6bfde97f2fe60d2a4a1f55f9c4ea476c9d87fa0fcd0c1c3592ad6a539ed14

In this transaction, the victim sent sfrxETH to a malicious address (0x4D9f77), a newly created contract with no transaction history.

However, examining the contract creation reveals that the phishing attack executed immediately upon deployment, draining the victim’s funds.

https://etherscan.io/tx/0x77c79f9c865c64f76dc7f9dff978a0b8081dce72cab7c256ac52a764376f8e52

Reviewing the execution trace shows that 0x4d9f7773deb9cc44b34066f5e36a5ec98ac92d40 was created via CREATE2.

Moreover, analyzing PinkDrainer-related addresses reveals daily creation of new contracts via CREATE2 for phishing purposes.

https://etherscan.io/address/0x5d775caa7a0a56cd2d56a480b0f92e3900fe9722#internaltx

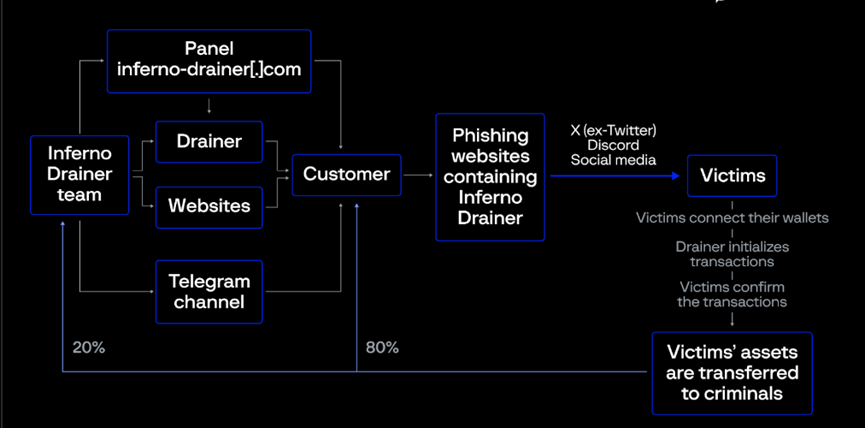

Drainer as a Service (DaaS)

Phishing attacks are becoming increasingly rampant and profitable, leading to the emergence of a black-market DaaS ecosystem. Notable operators include:

Inferno/MS/Angel/Monkey/Venom/Pink/Pussy/Medusa, etc. Attackers purchase these DaaS offerings to rapidly and easily build thousands of phishing sites and fake accounts—flooding the space like a flood, threatening user asset security.

Take Inferno Drainer as an example—a notorious phishing group embedding malicious scripts into various websites. For instance, they distribute fake versions of seaport.js, coinbase.js, wallet-connect.js, impersonating popular Web3 protocols (Seaport, WalletConnect, Coinbase) to trick users into integration or clicks. Once confirmed, user assets are automatically drained. Over 14,000 websites containing malicious Seaport scripts, over 5,500 with malicious WalletConnect scripts, over 550 with malicious Coinbase scripts, and over 16,000 malicious domains linked to Inferno Drainer have been identified, affecting over 100 crypto brands.

Under the DaaS model, 20% of stolen funds are automatically sent to Inferno Drainer’s organizers, while attackers keep 80%. Additionally, Inferno Drainer periodically offers free phishing site creation and hosting services. Sometimes, they charge 30% of scam proceeds. These hosted phishing sites cater to attackers who can drive traffic but lack technical skills or prefer not to host themselves.

How does this DaaS scam work? Below is a step-by-step breakdown of Inferno Drainer’s fraud scheme:

1) Inferno Drainer promotes its service via the Telegram channel “Inferno Multichain Drainer,” or through its website.

2) Attackers use DaaS tools to set up personalized phishing sites and spread them via X (Twitter), Discord, and other social media.

3) Victims are lured to connect their wallets by scanning QR codes or visiting phishing sites.

4) The drainer identifies the most valuable and easily transferable assets and initiates malicious transactions.

5) Victims confirm the transaction.

6) Assets are transferred to criminals. Of the stolen funds, 20% goes to Inferno Drainer developers, 80% to the attacker.

Security Recommendations

(1) Never click unknown links disguised as rewards, airdrops, or other enticing offers.

(2) Official social media accounts are increasingly compromised—official messages do not guarantee safety.

(3) Always verify authenticity when using wallets or DApps—beware of fake websites and apps.

(4) Treat every transaction confirmation or signature request with caution. Cross-check details such as recipient, content, and intent. Reject blind signing. Stay vigilant. Question everything. Ensure every action is intentional and secure.

(5) Users should understand common phishing methods and learn to identify red flags. Know common signature and approval functions and their risks. Understand fields like Interactive (interaction URL), Owner (approver address), Spender (authorized address), Value (amount authorized), Nonce, Deadline, transfer/transferFrom, etc.

IV. FIT21 Bill Explained

On May 23, 2024, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the FIT21 Act (Financial Innovation and Technology for the 21st Century Act) with 279 votes in favor and 136 opposed. President Biden announced he would not veto the bill and called on Congress to cooperate on a “comprehensive, balanced regulatory framework for digital assets.”

FIT21 aims to provide a clear pathway for blockchain projects to launch safely and effectively in the U.S., clarify jurisdictional boundaries between the SEC and CFTC, distinguish whether digital assets are securities or commodities, strengthen regulation of crypto exchanges, and better protect American consumers.

4.1 Key Provisions of the FIT21 Bill

Definition of Digital Asset

Bill text: IN GENERAL.—The term ‘digital asset’ means any fungible digital representation of value that can be exclusively possessed and transferred, person to person, without necessary reliance on an intermediary, and is recorded on a cryptographically secured public distributed ledger.

The bill defines “digital asset” as a fungible digital representation of value that can be transferred peer-to-peer without intermediaries and is recorded on a cryptographically secured public distributed ledger. This broad definition covers various digital forms—from cryptocurrencies to tokenized real-world assets.

Classification of Digital Assets

The bill outlines key criteria for determining whether a digital asset is a security or a commodity:

(1) Investment Contract (The Howey Test)

If purchasing a digital asset constitutes an investment where investors expect profits from entrepreneurial or third-party efforts, it is generally considered a security. This follows the U.S. Supreme Court’s standard established in SEC v. W.J. Howey Co., commonly known as the Howey Test.

(2) Use and Consumption

If a digital asset is primarily used as a medium for consuming goods or services rather than as an investment expecting capital appreciation—for example, if tokens are used to buy specific products or services—it may be classified as a commodity rather than a security, despite potential speculative trading in practice.

(3) Degree of Decentralization

The bill emphasizes the degree of decentralization of the underlying blockchain network. If a network is highly decentralized with no central authority controlling it, the associated asset is more likely to be treated as a commodity. This distinction is crucial because it determines whether the CFTC or SEC has jurisdiction.

The CFTC will regulate a digital asset as a commodity “if the blockchain or digital ledger on which it operates is functional and decentralized.”

The SEC will regulate a digital asset as a security “if the associated blockchain is functional but not strictly decentralized.”

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News