Vitalik's Latest Article: Reflections on the Bitcoin Block Size War

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Vitalik's Latest Article: Reflections on the Bitcoin Block Size War

The big-block faction is correct on the central issue—blocks need to be larger, preferably achieved through the simple and clean hard fork described by Satoshi.

Author: Vitalik Buterin

Translation: WuShuo Blockchain, Cat Brother

Recently, I finished reading (or rather, listening to) two major historical accounts of the great Bitcoin block size war of the 2010s—books that represent two opposing viewpoints:

● Jonathan Bier’s The Blocksize War, which tells the story from the small-block perspective

● Roger Ver and Steve Patterson’s Hijacking Bitcoin, which tells the story from the big-block perspective

Reading these two books about events I lived through and was somewhat involved in is fascinating. While I was already familiar with most of what happened and both sides’ narratives of the conflict's essence, there were still interesting details I either didn’t know or had completely forgotten, and seeing things from a fresh perspective was enlightening. At the time, I was a “big-blocker,” but a pragmatic medium-blocker who opposed extreme growth or absolutist claims such as transaction fees should never significantly rise. Do I still stand by my views from back then? I wanted to see—and find out.

How does Jonathan Bier portray the small-blockers' view of the block size war?

The original debate of the block size war centered on a simple question: Should Bitcoin increase its block size limit via a hard fork from the then-current 1 MB to a higher value, allowing more transactions, lowering fees—but at the cost of making it harder and more expensive to run and verify nodes on the blockchain network?

“[If blocks are much larger], you’ll need a large data center to run a node, and you won’t be able to do so anonymously.”—This key argument appeared in a video sponsored by Peter Todd, advocating for keeping block sizes small.

My impression from Bier’s book is that while the small-blockers did care about this specific concern—favoring conservative, modest increases to keep node operation accessible—they were even more concerned about how protocol-level decisions shaped this higher-order issue. In their view, changes to the protocol—especially “hard forks”—should be rare and require broad consensus among protocol users.

Bitcoin isn’t trying to compete with payment processors—there are plenty of those already. Instead, Bitcoin aims to be something unique and special: a new kind of money, free from control by central organizations and central banks. If Bitcoin developed a highly active governance structure—necessary to settle controversial adjustments like block size parameters—or became vulnerable to coordination by miners, exchanges, or other large corporations, it would permanently lose this valuable distinctiveness.

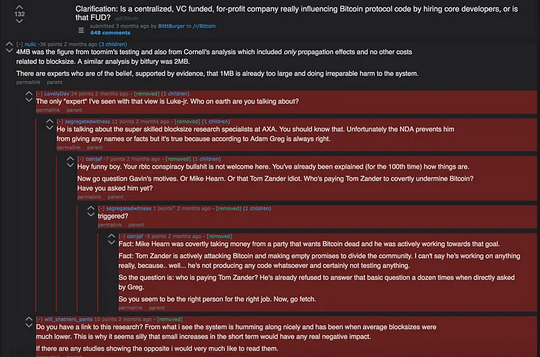

In Bier’s account, what disturbed the small-blockers most about the big-blockers was their repeated attempts to gather a relatively small number of major players to legitimize and push forward their preferred changes—this stood in direct opposition to the small-blockers’ vision of how governance should work.

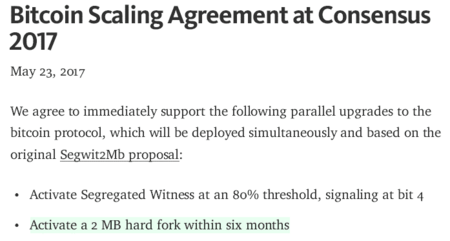

The New York Agreement, signed in 2017 by major Bitcoin exchanges, payment processors, miners, and other companies, was seen by small-blockers as a key example of an attempt to shift Bitcoin from user rule to corporate cartel rule.

How does Roger Ver portray the big-blockers' view of the block size war?

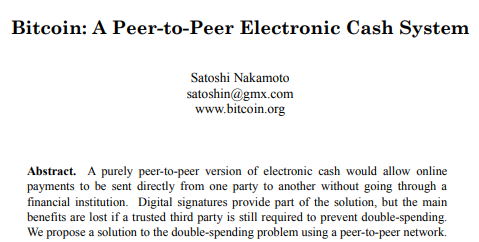

The big-blockers usually focused on one core concrete question: What should Bitcoin be? A store of value—digital gold—or a means of payment—digital cash? For them, the original vision, and the one all big-blockers agreed on, was clearly digital cash. The whitepaper even explicitly mentions this!

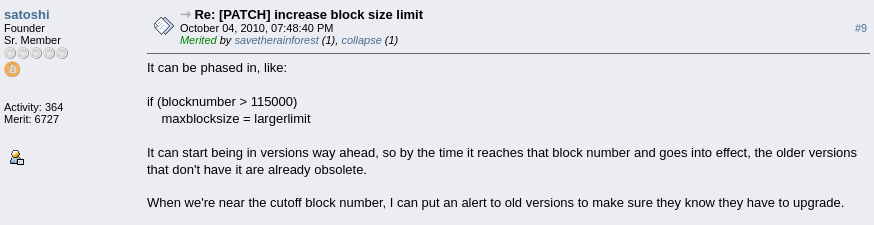

The big-blockers also frequently cited two other pieces of writing attributed to Satoshi Nakamoto:

1. The section in the whitepaper on Simplified Payment Verification, which discusses how individual users could use Merkle proofs to verify their payments are included when blocks become very large, without needing to validate the entire chain.

2. A post on Bitcointalk advocating gradual block size increases via hard forks:

For them, the shift from digital cash to digital gold was a pivot—one made by a small, tightly-knit group of core developers who believed that because they discussed the issue internally and reached a conclusion, they had the right to impose their view on the entire project.

The small-blockers did propose a solution where Bitcoin could serve as both cash and gold: Bitcoin would be a “Layer 1” focused on being gold, while “Layer 2” protocols built on top of Bitcoin, such as the Lightning Network, would provide cheap payments without requiring every transaction to go on-chain. However, these solutions were severely inadequate in practice, and Ver devotes several chapters to criticizing them. For instance, even if everyone switched to Lightning, eventually block size would still need to grow to accommodate hundreds of millions of users. Moreover, receiving coins trustlessly on Lightning requires running an online node, and to ensure your coins aren’t stolen, you need to check the chain weekly. These complexities, Ver argues, will inevitably push users toward centralized interactions with Lightning.

What are the key differences in their perspectives?

Ver agrees with the small-blockers on the description of the concrete debate: both sides acknowledge that small-blockers prioritize ease of running nodes, while big-blockers prioritize low transaction fees. They both admit that reasonable differences in belief were a key driver of the debate.

But Bier and Ver offer starkly different accounts of most deeper issues. For Bier, the small-blockers represent users resisting a small but powerful coalition of miners and exchanges trying to seize control of the blockchain for their own benefit. Small blocks preserve decentralization by ensuring ordinary users can run nodes and verify the blockchain. For Ver, the big-blockers represent users resisting a small group of self-appointed high priests and venture-capital-backed firms (i.e., Blockstream) who profit from the second-layer solutions necessitated by the small-block roadmap. Big blocks preserve decentralization by ensuring users can afford on-chain transactions without relying on centralized Layer 2 infrastructure.

Where I saw the closest thing to “agreement on terms” between the sides was Bier’s book acknowledging that many big-blockers acted in good faith, even recognizing their legitimate frustration with small-block forum moderators censoring dissenting views—though he frequently criticizes the big-blockers’ incompetence. Meanwhile, Ver’s book tends to attribute malicious intent or even conspiracy theories to the small-blockers, but rarely questions their competence. This reflects a common political metaphor I’ve heard often: “the right thinks the left is naive, the left thinks the right is evil.”

How did I view the block size war then? How do I view it now?

Room 77, a restaurant in Berlin that once accepted Bitcoin, was at the heart of the Bitcoin district, where many restaurants accepted Bitcoin. Unfortunately, the dream of Bitcoin payments faded in the latter half of the decade, and I believe rising fees were a key reason.

During the block size war, I generally sided with the big-blockers. My support rested on several key points:

-

A core original intention of Bitcoin was digital cash, and high fees could kill this use case. While Layer 2 protocols theoretically could offer lower fees, the whole concept was untested, and it was irresponsible for the small-blockers to stick to a small-block roadmap while knowing so little about how Lightning would actually perform. Today, real-world experience with Lightning makes pessimistic views more widespread.

-

I was unconvinced by the small-blockers’ “meta-level” arguments. They often claimed “Bitcoin should be controlled by users” and “users don’t support bigger blocks,” yet never clearly defined who “users” are or how to measure their preferences. The big-blockers implicitly proposed at least three ways to count users: hash power, public statements from prominent companies, and social media discussion—each of which the small-blockers rejected. The big-blockers didn’t organize the New York Agreement because they liked “cartels,” but because the small-blockers insisted any controversial change required consensus among “users,” and getting major stakeholders to sign a statement seemed like the only practical way forward.

-

Segregated Witness, the small-blockers’ proposal for a modest block size increase, seemed unnecessarily complex compared to a simple hard fork. The small-blockers eventually adopted the dogma of “soft forks good, hard forks bad” (which I strongly oppose), and designed their block size increase to fit this rule—even though Bier admits this introduced serious complexity that many big-blockers couldn’t understand. It felt less like genuine caution and more like arbitrarily choosing one kind of caution (no hard forks) over another (keeping code and specs simple and clear) to suit their agenda. Eventually, the big-blockers also abandoned “simplicity,” turning to ideas like Bitcoin Unlimited’s adaptive block size increases, which Bier (rightfully) criticizes harshly.

-

The small-blockers did engage in some seriously unsavory social media censorship to enforce their views, culminating in Theymos’ infamous quote: “If 90% of /r/Bitcoin users think these policies are intolerable, I hope that 90% of /r/Bitcoin users leave.” (Note: “/r/” denotes a subreddit on Reddit.)

Even relatively moderate pro-big-block posts were often deleted. Custom CSS was used to make these deleted posts invisible.

Ver’s book focuses heavily on the first and fourth points, part of the third, and also introduces theories of misconduct tied to financial motives—namely, that the small-blockers founded a company called Blockstream, which would build Layer 2 protocols atop Bitcoin while simultaneously promoting the idea that Bitcoin’s Layer 1 should remain restricted, thus making their commercial Layer 2 networks necessary. Ver doesn’t dwell much on the philosophy of Bitcoin governance because, for him, “Bitcoin is governed by miners” is a sufficient answer. On this point, I disagree with both camps: both the vague “we reject actually defining user consensus” and the extreme “miners should control everything because they have aligned incentives” are unreasonable.

At the same time, I recall being deeply disappointed by the big-blockers on several key points—a sentiment echoed in Bier’s book. The worst, shared by both me and Bier, was that the big-blockers never agreed on any realistic principle for limiting block size. A common slogan was “block size should be decided by the market”—meaning miners should decide freely, and others could choose whether to accept those blocks. I strongly opposed this, arguing it was an extreme distortion of the “market” concept. When the big-blockers eventually split off into their own chain (Bitcoin Cash), they abandoned this idea and set a fixed 32 MB limit.

Back then, I actually did have a principled approach to deciding block size limits. As I wrote in a 2018 post:

“Bitcoin maximizes predictability of the cost of reading the blockchain, while minimizing predictability of the cost of writing to it—resulting in excellent performance on the former metric, but catastrophic on the latter. Ethereum’s current governance model strikes a moderate level of predictability on both.”

I later reiterated this point in a 2022 tweet. Essentially, the philosophy is: we should balance the cost of writing to the chain (transaction fees) against the cost of reading it (node software requirements). Ideally, if demand for blockchain usage increases 100-fold, we should split the pain—increasing block size tenfold and fees tenfold (since demand elasticity for transaction fees is close to 1, this is roughly feasible in practice).

Ethereum has indeed taken a moderate-block approach: since its 2015 launch, chain capacity has increased about 5.3x (possibly 7x including calldata repricing and blobs), while fees have risen from near-zero to a noticeable but not excessive level.

Yet this compromise-oriented (or “concave”) approach was never accepted by either side; to one it might seem too “centrally planned,” to the other too “vague.” I feel the big-blockers bear more blame here; the small-blockers were initially open to modest increases (e.g., Adam Back’s 2/4/8 plan), but the big-blockers refused to compromise, quickly shifting from advocating a one-time increase to a particular large value to a broader philosophy that almost any non-trivial block size limit was illegitimate.

The big-blockers also began arguing that miners should control Bitcoin—Bier effectively criticized this, pointing out that if miners tried to modify protocol rules for other purposes—like giving themselves higher rewards—they’d likely abandon this stance quickly.

One of Bier’s main criticisms of the big-blockers in his book is their repeated incompetence. Bitcoin Classic was poorly coded, Bitcoin Unlimited was unnecessarily complex, lacked erasure coding for a long time (a choice that severely undermined their chances of success, !!), and had serious security vulnerabilities. They loudly advocated for multiple implementations of Bitcoin software—a principle I agree with and Ethereum follows—but their “alternative clients” were merely forks of Bitcoin Core with a few lines changed to increase block size. In Bier’s narrative, their repeated technical and economic missteps caused growing numbers of supporters to leave. Major big-block supporters believed Craig Wright’s false claim to be Satoshi, further damaging their credibility.

Craig Wright, a fraudster pretending to be Satoshi. He often uses legal threats to remove criticism, which is why MyFork is the largest surviving online repository of evidence proving he’s a fraud. Unfortunately, many big-blockers fell for Craig’s act because he parroted big-block rhetoric and told them what they wanted to hear.

Overall, reading these two books, I found myself agreeing more often with Ver on macro issues, but more often with Bier on concrete details. To me, the big-blockers were right on the central issue—that blocks needed to be bigger, preferably via the simple, clean hard fork described by Satoshi—but the small-blockers made fewer embarrassing technical mistakes and their positions led to fewer absurd outcomes.

The block size debate was a unilateral competence trap

Reading these two books gave me an overall impression of political tragedy—a pattern I’ve seen repeatedly in various contexts, including crypto, corporate politics, and national politics:

One side monopolizes all the competent people but uses that power to advance narrow, biased agendas; the other side correctly identifies the problem but becomes so consumed by opposition that it fails to develop the technical capability to execute its own plans.

In many such cases, the first group is criticized as authoritarian, but when you ask its (often numerous) supporters why they back it, they reply that the opposition would just complain—and if they ever gained power, they’d fail within days.

To some extent, it’s not the opposition’s fault: without platforms to execute and gain experience, it’s hard to become skilled at execution. But in the block size debate, it was especially clear that the big-blockers seemed utterly unaware of the need for executional competence—they thought being right on the block size issue alone would guarantee victory. The big-blockers ultimately paid dearly for focusing on opposition instead of building: even after forking into their own chain (Bitcoin Cash), they split twice more in short order before the community finally stabilized.

I call this the unilateral competence trap. It seems to be a fundamental challenge for anyone trying to build a political entity, project, or community they hope will be democratic or pluralistic. Smart people want to work with other smart people. If two groups are roughly balanced, individuals may choose the side that better aligns with their values, creating stable equilibrium. But if the tendency is too lopsided, it enters a different equilibrium that appears difficult to reverse. To some extent, the opposition can mitigate the unilateral competence trap by consciously recognizing the problem and cultivating capability. Often, opposition movements don’t even reach this stage. But sometimes, mere awareness isn’t enough. If there were stronger, deeper methods to prevent and escape unilateral competence traps, we’d all benefit greatly.

Less conflict, more tech

One glaring absence stood out above all else while reading these books: the word “ZK-SNARK” appears nowhere in either. There’s little excuse: even by the mid-2010s, ZK-SNARKs and their potential for scalability (and privacy) were widely known. Zcash launched in October 2016. Gregory Maxwell briefly explored ZK-SNARKs’ scalability implications in 2013, yet they seem entirely absent from discussions about Bitcoin’s future roadmap.

The ultimate way to ease political tensions isn’t compromise, but new technology: discovering entirely new approaches that give both sides more of what they want. We’ve seen several such examples in Ethereum. A few come to mind:

-

Justin Drake championed BLS aggregation, enabling Ethereum’s proof-of-stake to handle more validators, reducing the minimum stake from 1500 to 32 ETH with almost no downsides. Recent progress on signature batching could push this even further.

-

EIP-7702 achieves ERC-3074’s goals in a way far more compatible with smart contract wallets, helping to defuse a long-standing controversy.

-

Multi-dimensional gas, starting with its implementation on blobs, has helped increase Ethereum’s capacity to handle rollup data without increasing worst-case block size, minimizing security risks.

When an ecosystem stops embracing new technology, it inevitably stagnates and grows more contentious: political debates over “I get 10 more apples” and “you get 10 more apples” are inherently less divisive than debates over “I lose 10 apples” and “you lose 10 apples.” Losses hurt more than gains, and people are more willing to break shared political rules to avoid losses. This is a key reason why I’m deeply uneasy about degrowth and “we can’t solve social problems with technology” ideologies: strong reasons suggest that competing over who gains more, rather than who loses less, is indeed more conducive to social harmony.

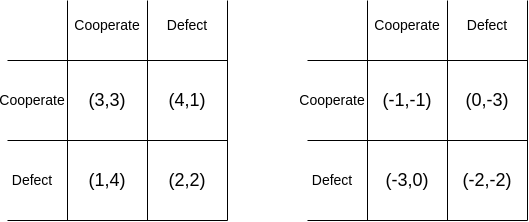

In economic theory, the two prisoner’s dilemmas are identical: the game on the right can be seen as the game on the left plus an independent (irrelevant) step where both players lose four regardless of actions. But in human psychology, the two games may feel very different.

A key question for Bitcoin’s future is whether it can become a technologically forward-looking ecosystem. Inscriptions and later BitVM developments create new possibilities for Layer 2, improving what Lightning can do. Hopefully Udi Wertheimer is right that ETH getting an ETF means the end of Saylorism and a renewed recognition that Bitcoin needs technological improvement.

Why do I care about this?

I care about analyzing Bitcoin’s successes and failures not to denigrate Bitcoin and elevate Ethereum. In fact, as someone who enjoys understanding social and political dynamics, I see Bitcoin’s richness as a strength—it’s sociologically complex enough to generate such deep and fascinating internal debates and splits that two full books can be written about them. Rather, I care because Ethereum and other digital (and even physical) communities I care about can learn a great deal from understanding what happened, what was done well, and what could be improved.

Ethereum’s focus on client diversity stems from observing Bitcoin’s failure due to having only one client team. Its version of Layer 2 solutions comes from understanding how Bitcoin’s limitations constrain the trust properties of Layer 2 built atop it. More broadly, Ethereum’s explicit effort to cultivate a diverse ecosystem is largely aimed at avoiding the unilateral competence trap.

Another example that comes to mind is the network state movement. Network states are a new digital secession strategy, allowing like-minded communities to partially escape mainstream society and build their visions of cultural and technological futures. But the experience of Bitcoin Cash (post-fork) shows a common failure mode for movements that try to solve problems via forking: they may keep splitting, never truly cooperating. The lessons from Bitcoin Cash extend far beyond Bitcoin Cash itself. Just like rebellious cryptos, rebellious network states need to learn how to actually execute and build—not just throw parties, share vibes, and compare memes of modern barbarism versus 16th-century European architecture on Twitter. Zuzalu, in part, is my own attempt to help drive that change.

I recommend reading both Bier’s The Blocksize War and Patterson and Ver’s Hijacking Bitcoin to understand a defining moment in Bitcoin’s history. In particular, I suggest reading them not just with a Bitcoin-focused mindset—but as records of the first true high-stakes civil war in a “digital nation.” The lessons they offer will be vital for building other digital nations in the decades ahead.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News