The Illusion of Scarcity: NFTs Are Neither a Good Investment Nor a Good Business

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The Illusion of Scarcity: NFTs Are Neither a Good Investment Nor a Good Business

What this article writes about is both NFTs and yet more than just NFTs.

Author: Nakamoto Uikyou

Key Takeaways:

· The real business model of NFTs is not buying and selling scarcity or collectible value, but leveraging misleading information to attract a tiny number of ultimate buyers—using high-priced NFTs to gain trust, then selling other NFTs at falsely inflated valuations.

· There has always been confusion between an individual's "perceived price" and the market's "consensus price," yet an isolated transaction price is never equivalent to a "market consensus price." In reality, genuine NFT buyers are extremely limited. The shallow market depth of NFTs makes their pricing mechanism incapable of achieving what is commonly assumed as "consensus pricing."

· Issuing NFTs involves almost zero barriers and minimal cost, which inevitably renders the so-called "scarcity" of NFTs an illusion. Countless NFTs with similar "rarity" are mass-produced, making them not scarce at all, but rather excessively abundant.

· The market has already priced in the false scarcity and actual oversupply of NFTs. The hidden market consensus is that NFT valuations are not recognized, resulting in NFTs having prices but no buyers.

· Most investors and issuing teams cannot profit from NFTs. Investors are unlikely to hit the jackpot by purchasing a lucky NFT; instead, they're far more likely to become the "last buyer" (or possibly the only genuine buyer) of an overpriced NFT. Most issuing teams merely mechanically copy the NFT product format without realizing that creating a blue-chip like BAYC requires substantial financial resources and strategic insight.

· Seemingly impartial NFT trading markets and data platforms are part of the illusion—they use absurd statistics to mislead investors and issuers into incorrect valuation and pricing decisions.

· To revive the NFT sector, we must abandon rigid fixation on narratives of collectibility and scarcity, correct misconceptions about the NFT market, and stop misallocating resources.

· This article discusses not just NFTs, but broader market illusions waiting to be exposed. Its goal is simply to spark discussion.

There’s an unwritten rule in venture capital: when everyone rushes into an investment sector, it ceases to be a high-return opportunity.

Profit-seeking behavior creates equilibrium—any obvious profit space is quickly seized until excess profits either vanish or exist only in overlooked or once-in-a-lifetime opportunities. (That’s why I prefer trading opportunities others don’t understand.)

While not an absolute truth, this principle often holds true in investing and business, which is why I’ve long been puzzled by the booming NFT market two years ago:

If launching an NFT is such a simple, nearly cost-free business model accessible to virtually anyone, where does the massive profit come from?

If the path to NFT profitability was suddenly discovered overnight and ignited widespread imagination about future commercial landscapes, how could it still be considered a promising sector?

Crowding and growth, low barriers and high returns—these cannot coexist. If they appear to, one must be fake.

Failing to recognize this relationship inevitably leads to irrational profit-seeking and disastrous decisions.

This article aims to clarify why the reality of NFTs and NFT-like assets differs sharply from popular perception.

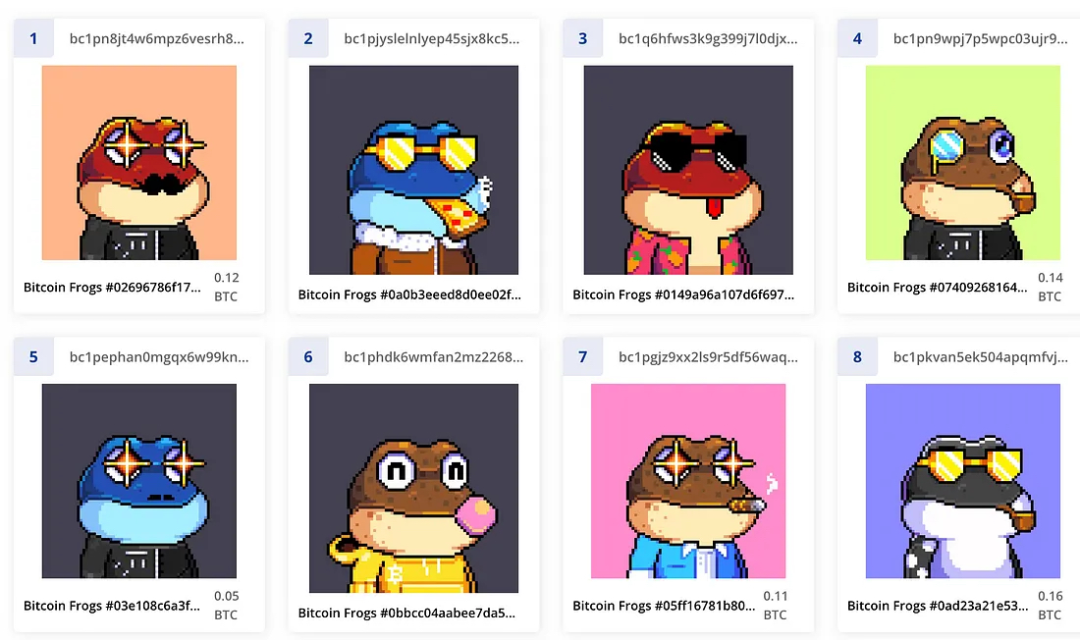

Two years later, market understanding of NFTs hasn't improved much. A large number of teams continue pouring significant costs into projects based on flawed assumptions. Despite previous market downturns, new NFTs keep launching relentlessly, each hoping theirs will join the blue-chip ranks. As I began writing this article, CryptoSlam listed 30 projects awaiting minting—not to mention the constant stream of new BTC-based NFTs riding the Bitcoin ecosystem narrative wave.

Bitcoin Frogs

The pursuit of profit unleashes boundless creativity—but more often leads people to follow trends blindly through manipulation and deception. Free markets allow free choice, but also permit the creation of illusions and freedom to be deceived by them.

Understanding these illusions is crucial—it teaches us self-protection and prevents further misallocation of resources.

1. The Size of the NFT Market

NFT research reports have long loved citing the total market cap of NFTs, portraying it as a massive market—especially when it reached a staggering $3 trillion in November 2021. Reports also highlight the incremental users NFTs brought to Web3.0: nearly 5 million unique users remain active today, with cumulative buyers exceeding 12.6 million.

Perhaps due to human confirmation bias, people eagerly seek evidence supporting the idea that the NFT market is full of potential and golden opportunities, rather than attempting to disprove its prosperity.

Thus, whether two years ago or today—with the market cap down 99% to just $6.7 billion—almost no one questions the methodology behind calculating NFT market cap.

NFT market cap = floor price (sometimes average price) × total supply; the overall NFT market cap is a simple sum of all individual NFT market caps.

This formula is questionable even for traditional securities valuation, let alone NFTs—its ineffectiveness rivals using national GDP to measure individual household living standards.

Generally, the lower the float market cap of a stock, the higher the risk of valuation bubbles and distortions. Most NFT series have genuine circulation rates of only 1%-2% of total supply, with non-blue-chips even lower. Crucially, as explained below, NFT prices do not stem from sufficient capital competition, making their value reflection even weaker.

Inflated prices combined with negligible turnover create paper wealth—an ordinary "accounting trick" that causes market participants to grossly overestimate NFT product value and market potential, ultimately fooling themselves with false prosperity.

Ignoring irrelevant metrics is one issue; conspicuously falsifiable data rarely gets mentioned—such as the fact that cumulative NFT trading volume reached only $86 billion as of November 28, less than Bitcoin’s trading volume on Binance over two months.

The stock market is full of various fraudsters, but volume remains the sole exception.

The NFT market is far smaller than imagined. Reorganizing available data reveals that the only truly "massive" aspect of this market is its bubble.

2. Measuring Liquidity: The Real Buyers in the NFT Market

I've long wondered what metrics beyond cumulative trading volume can effectively measure the scale and liquidity of the NFT market.

A scientist friend (@darmonren) inspired me. He casually scraped Cryptopunks transaction data and found most punks had never traded at all.

This discovery unveiled the liquidity crisis in the NFT market, suggesting a hypothesis: perhaps the lack of liquidity stems from most NFTs lacking genuine buyers.

To test this, I scraped data from other blue-chip NFTs besides Cryptopunks, revealing some interesting patterns. Next, I'll use BAYC as an example.

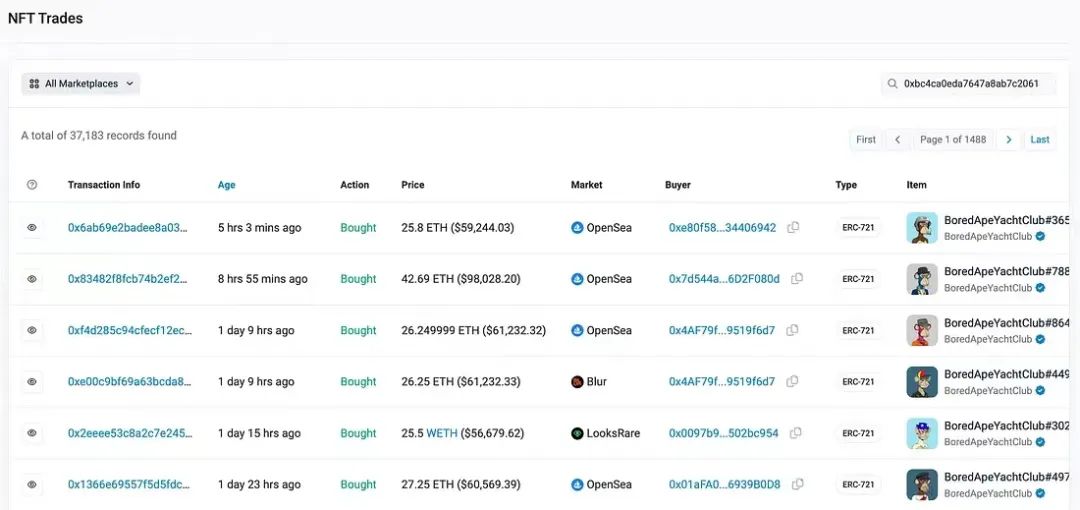

As of November 28, 2023, Etherscan recorded 36,990 BAYC transactions across eight major NFT marketplaces. Note: these are not all BAYC transfer records—they represent a subset.

Transaction count increased from 36,990 to 37,183 by editing date

As shown, among 10,000 BAYCs involved in 36,990 trades, 10% have never traded, 71% traded fewer than five times in their lifetime, fewer than 20 BAYCs changed hands over 30 times, only four exceeded 50 trades, and none surpassed 100 trades.

These figures underwent preliminary cross-verification.

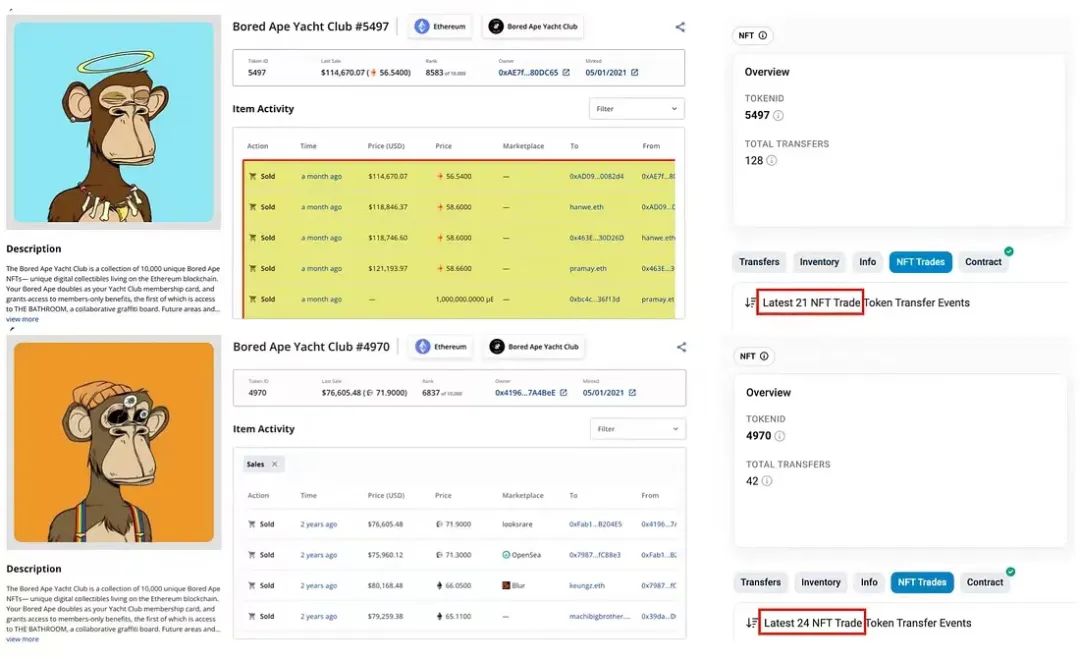

I selected 100 samples each from extreme values—those traded more than 10 times and those traded exactly once—and compared their token IDs against sales data collected by Cryptoslam.

Cryptoslam also captures data from unnamed marketplaces beyond the eight listed above. When an ID's entire transaction history is confined to these eight platforms, both datasets align. All 100 single-trade samples matched perfectly.

However, discrepancies emerged. For instance, BAYC#5497 showed 21 trades on Etherscan but 54 on Cryptoslam—21 from Blur and OpenSea, plus 33 from unrecorded exchanges. Similarly, BAYC#4970 appeared with 17 trades on Cryptoslam versus 24 on Etherscan.

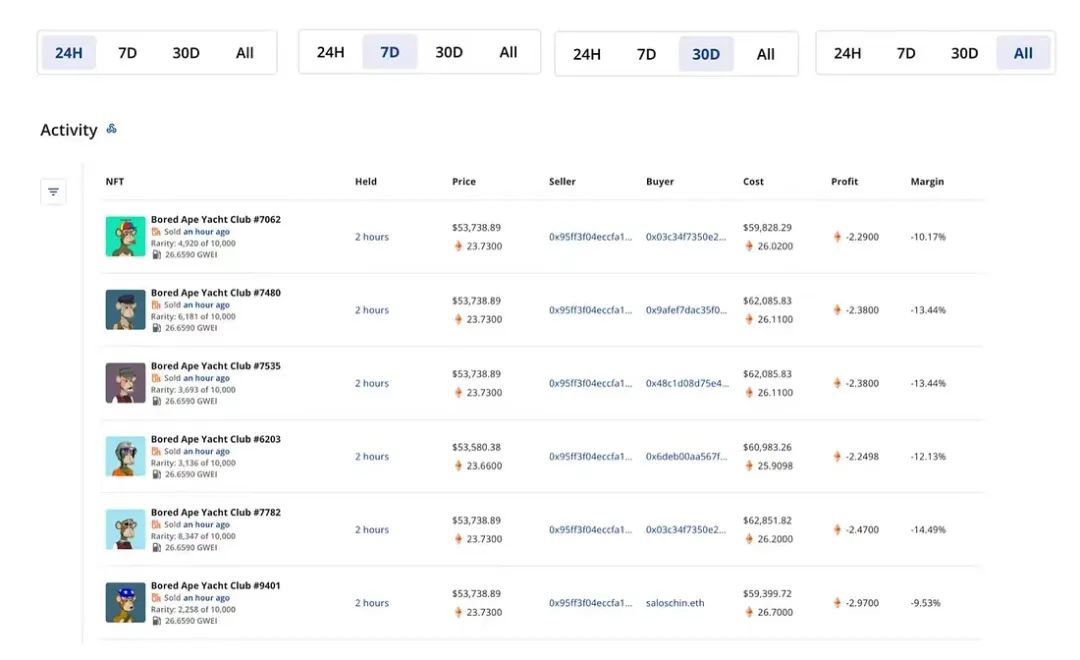

In reality, discrepancies cluster around BAYCs featured on Cryptoslam’s activity leaderboard—coverage nearly 100%. Close inspection shows identical BAYCs topping 24-hour, 7-day, and 30-day leaderboards, frequently trading across unnamed exchanges, hence showing higher historical trade counts than Etherscan records.

Regardless of what caused these spikes, since we’re measuring long-term BAYC turnover distribution, such sudden anomalies should be excluded.

Therefore, this doesn’t affect our conclusion—the vast majority (99%) of BAYCs lack a market (i.e., any meaningful chance of resale), because they don’t have a sizable buyer base.

Among the remaining 1%, if we consider each transfer as a new independent buyer, fewer than 30%—just 17 BAYCs—have more than 30 buyers.

In other words, during the past 950 days, each of these 17 BAYCs attracted fewer than 30 buyers; only one out of 10,000 BAYCs ever had 60 historical buyers.

This distribution pattern holds true for other blue-chip NFTs as well.

BAYC listing rate on OpenSea is 2%

One might ask: if 90% of BAYCs have traded at least once, how can we claim NFTs lack buyers?

In fact, checking OpenSea listing rates alone reveals clues—blue-chip NFTs with 10,000 units typically list only 1%-2%, meaning just 100–200 items are actively for sale.

If all traded NFTs were genuinely sold, why would listing rates be so low?

According to scraped data, 1,729 BAYCs have exactly one lifetime transaction record. If each were bought by an independent genuine buyer, how could only 200 BAYCs be listed for sale? While manipulators may control listing rates, profit-driven participants have no incentive to buy without reselling—capital shouldn’t sit idle voluntarily.

Now, I hope you fully understand why the NFT market suffers from illiquidity.

3. Lower Liquidity Than Imagined

We often talk about liquidity, but now it’s time to define it clearly. I’ve observed that when people discuss NFT liquidity, they usually refer to both the asset’s inherent liquidity and the market’s available capital pool.

Asset liquidity refers to how quickly and easily an asset can be sold at fair market value. Liquid assets can be sold rapidly at current prices without heavy discounts or high fees.

Meanwhile, available market capital indicates funding availability within the market, determined by the ratio of funds to assets—it represents liability-side liquidity.

Liquidity shortage in the NFT market exists on both the asset side and the liability side.

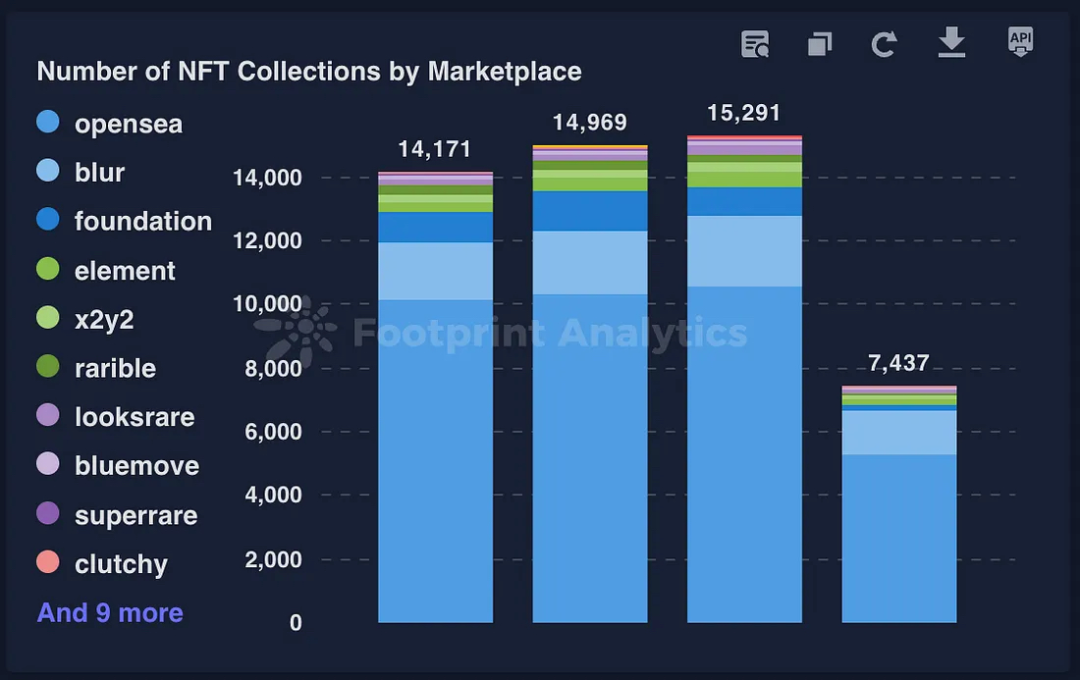

First, NFT marketplaces have made minting and issuance extremely easy, causing NFT supply to grow virally. The surge in tradable NFTs squeezes overall market liquidity.

Second, the non-fungible nature means each NFT constitutes its own niche market. Even PFP series place each NFT in a separate trading environment, fragmenting liquidity.

NFT characteristics inherently fragment liquidity. Worse, the absence of mechanisms monitoring marginal liquidity changes exacerbates the problem. In FT markets, any change in marginal capital directly impacts price—increased or decreased liquidity manifests immediately in price movements.

But in NFT markets, marginal liquidity and price are disconnected. Capital withdrawal doesn’t reflect directly in prices; even without new inflows, existing capital rotation can push up NFT prices, inflating the market’s paper valuation.

When no mechanism measures or locks available capital, artificial prosperity emerges—despite dwindling liquidity, NFT book prices and total market caps remain high.

For NFT investors, lack of buyers combined with survivorship bias perpetuating get-rich-quick myths results in being lured in by high prices—only to miss the lottery NFT and end up as the “last buyer.”

4. The Myth of Consensus Pricing

So, can NFT prices be trusted?

Common belief holds that NFT prices are reliable because broad discourse suggests both market participants and observers accept NFTs’ “consensus pricing” mechanism.

Consensus and scarcity are cited as explanations for NFT expensiveness.

In my view, “consensus pricing” is a favored elegant yet vague concept in crypto—a typical manifestation of market irrationality.

Re-examining the logic behind “consensus pricing” reveals that “consensus” actually refers to popularity metrics and collective sentiment, corresponding to two assumptions:

Assumption One: High-profile NFT creators with large fanbases naturally possess strong consensus foundations, as celebrity fans will enthusiastically provide liquidity and turnover, giving NFTs appreciation potential.

Assumption Two: People seek belonging and self-expression, willing to pay premium prices for emotionally resonant NFTs.

This isn’t consensus pricing—it’s popularity-based and emotion-driven pricing.

The fame assumption is easily debunked by crashing prices and real on-chain data—the true market consensus.

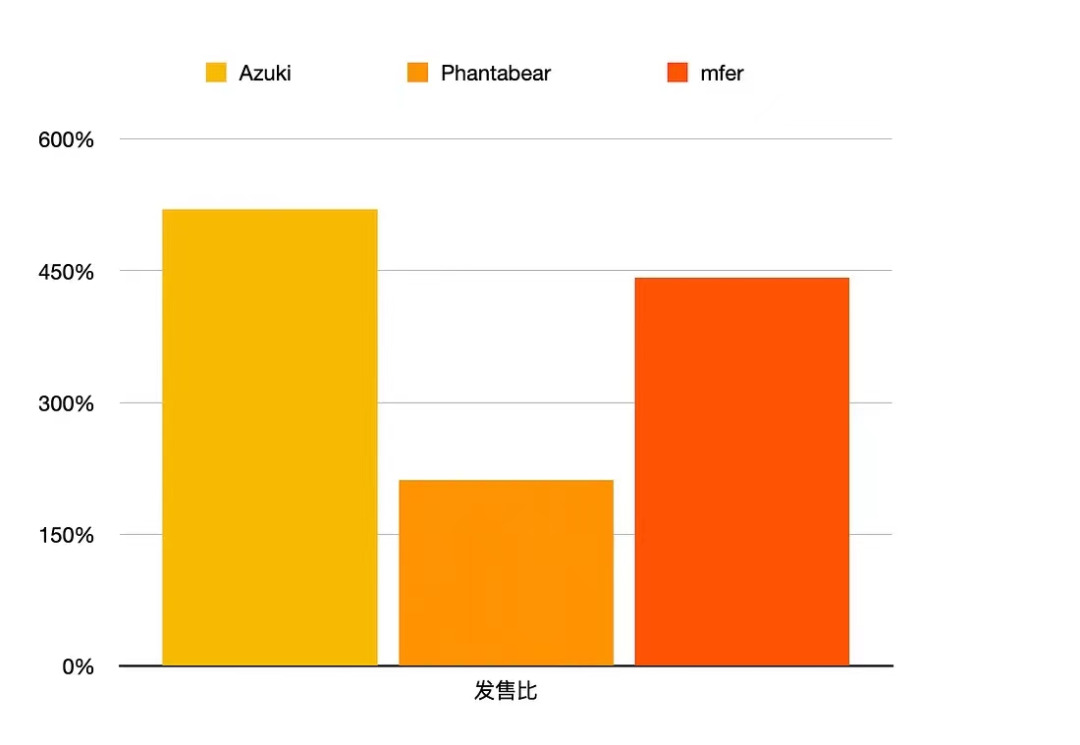

Take Jay Chou Bears: they seemed briefly “hot,” yet their sell-through rate was worse than harder-to-sell BAYC or Punk (sell-through = issuance quantity / total trades, used here as a rough proxy for average turnover).

Emotion-focused mfer and Azuki actually had higher sell-through rates (even surpassing BAYC and Cryptopunks), indicating stronger “consensus.” I suspect this relates to audience targeting—celebrity fans aren’t necessarily NFT adopters; there aren’t more Jay Chou fans willing to spend than anime lovers or “fuck yeah” chanters.

In short, converting celebrities’ fans into NFT adopters—or finding celebrity fans within NFT adopters—is far harder than tapping into emotional needs of core NFT users.

Still, even emotions drive trading intent better than fame, the outcome still falls short of forming real “consensus.”

As previously noted, each NFT represents a distinct micro-market. If 99% of NFTs have only one or two lifetime customers—or none at all—who forms their “consensus”? Can 30 buyers constitute consensus?

How can we assign fair prices to tens of thousands of personalized markets individually?

NFT pricing theory conflates individual “perceived price” with market “consensus price.” In reality, genuine buyers are few. Among traded NFTs, 81% of holders had fewer than five counterparties—including wash trades by insiders. The shallow price depth and infrequent turnover mean NFTs cannot achieve “consensus pricing.” Their mechanism isn’t general “consensus pricing,” but speculative pricing by limited investors—buying based on growth expectations, not value recognition.

But this isn’t the sole reason NFT prices are untrustworthy.

5. The Emperor’s New Clothes: The Illusion of NFT Scarcity

Another factor used to price NFTs is scarcity, but once we grasp the abundance of NFTs on the asset side, the scarcity narrative collapses.

The NFT business model was built around scarcity storytelling—a crude imitation of luxury goods marketing.

I understand the origin of this logic—fragmented classical economic theories dominate NFT participants’ thinking.

People may not fully believe in the invisible hand as ideal economic coordination, yet selectively apply it to NFT markets.

We know simply that supply and demand determine price: oversupply lowers prices, shortages raise them—ignoring elasticity.

NFT issuers want rising prices, so they artificially engineer “shortages.”

The first sleight of hand is equating non-fungibility with scarcity. Then, issuers classify attributes within collections, making some “rarer” than others.

Yet genuine market demand for NFTs is ignored.

Prices are influenced by supply but determined by demand. NFT demand boils down to consumption or investment. Consumption demands value-for-money, which NFTs clearly lack at high prices—leaving only investment demand. But unlike genuinely rare antiques (which are irreplaceable though always in demand), endlessly producible NFTs have negligible consumption value and zero true investment worth.

In real art markets, painting prices follow a Pareto distribution: a few famous artists command astronomical prices while most artists struggle to sell.

The irony lies here: although artificial scarcity is manufactured, the market hasn’t widely accepted it.

Data shows even top-tier blue-chip series fail to achieve full turnover (in fact, market interest in the “most promising” 200 remains limited). No metric currently gauges real NFT demand, but oversupply is undeniable. While individual NFT series have capped supply, the overall NFT asset supply is excessive.

Monthly newly issued NFT counts from October 2023 to January 2024

This precisely shows that the fairy tale of sky-high NFT prices and trillion-dollar valuations attracted not “buyers,” but NFT issuers.

Yet given most NFTs fade into obscurity, most issuers clearly misunderstand what drives NFT success.

6. Who Inflated the Bubble?

Due to limited real demand and liquidity, issuing, selling, or investing in NFTs is rarely profitable—especially with high upfront costs.

Then how was it initially packaged as a trillion-dollar industry brimming with excess profits?

In 2021, I chronicled the NFT market’s evolution, spouting nonsense about digital scarcity, cultural transformation, and crypto expression. Looking back, the key takeaway was realizing NFTs became viable commercially only after crypto art platforms like Nifty Gateway and Async Art orchestrated high-profile auctions starting in 2020, culminating in Christie’s and Sotheby’s elevating Beeple, Pak, and Cryptopunks.

In short, crypto art platforms and traditional auction houses progressively amplified NFT market hype and valuations.

In 2020, AsyncArt facilitated the $344,915 sale of “First Supper” in its second month, followed by frequent six-figure transactions.

Nifty Gateway held three curated Beeple auctions from October to December 2020, totaling 258 ETH (then ~$180,600).

In December 2020, Pak became the first crypto artist to earn over $1 million.

In March 2021, Beeple’s “Everydays: The First 5,000 Days (2008–21)” sold for $69.34 million. That same month, Sotheby’s announced an April auction for Pak, marking its official entry into NFTs.

But the pivotal moment came in February 2021, when CryptoPunk #6965 sold for 800 ETH (~$1.5M), followed by CryptoPunk #7804 fetching ~$7.5M on March 11. Consequently, Christie’s announced on April 8 that it would auction Cryptopunks during its 21st Century Evening Sale.

The rise of PFPs and explosive expansion of NFT assets began shortly thereafter.

April 23, 2021: BAYC launched minting at 0.08 ETH

May 3, 2021: Meebits launch

July 1, 2021: Cool Cat

July 28, 2021: World of Women

September 9, 2021: CrypToadz

October 17, 2021: Doodles open mint

December 12, 2021: CloneX

January 12, 2022: Azuki

March 31, 2022: Beanz

April 16, 2022: Moonbirds

Above are launch dates of the top ten blue-chip PFPs globally.

The myth crafted by crypto art platforms and traditional auction houses around Cryptopunks inspired the sharpest, most capital-savvy speculators in the space—thus BAYC emerged.

"Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please."

— Marx

Bull markets always arrive this way—random elements are deliberately amplified into contagious narratives and replicable products.

As pioneers of PFPs, Cryptopunks and BAYC established the foundational framework for subsequent NFTs—BAYC emulated Cryptopunks' structure, while others copied BAYC’s (superficial) business model and promotional tactics.

7. The Magician’s Trick — NFT Price Manipulation

To the then-current NFT market, the BAYC founding team were genius-level masterminds.

While most remained clueless about NFTs, BAYC’s team had already devised how to exploit cognitive biases and perceptual blind spots to turn BAYC into the next legend.

Returning to our earlier point: only manipulators have incentives to control NFT listing rates—market control begins at minting.

I scraped 5,000 BAYC mint records—nearly half the total supply—and found: 668 unique addresses participated, one address minted 16% (800 BAYCs), and 46% (2,311 BAYCs) were concentrated in 20 addresses.

Moreover, over 87% of BAYCs were minted in bulk by single addresses (more than four

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News