SharkTeam: Stablecoin Security and Regulation from the Perspective of On-Chain Data

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

SharkTeam: Stablecoin Security and Regulation from the Perspective of On-Chain Data

As everyone knows, cryptocurrency prices are extremely volatile. To establish a reasonable pricing benchmark in the cryptocurrency market and lay the foundation for liquidity across various cryptocurrencies, stablecoins emerged.

Author: SharkTeam

I. Overview of Stablecoins

It is well known that cryptocurrency prices are highly volatile. To establish a reliable pricing benchmark within the crypto market and lay the foundation for liquidity across various cryptocurrencies, stablecoins were created. Their design objective is to maintain stable value by pegging to stable assets such as the US dollar. As a result, the value of stablecoins is typically fixed at a 1:1 exchange rate with assets like the US dollar, euro, renminbi, or commodities such as gold.

Beyond their value-stability feature, stablecoins also serve an important role as a means of payment, enabling users to conduct payments and transfers conveniently. Due to their relatively stable value, stablecoins facilitate commercial transactions and payments. Serving as base currencies in OTC, DeFi, and CeFi ecosystems, they provide users with broader access to financial services and product options.

Based on their underlying mechanisms and issuance models, stablecoins can be categorized into four types:

(1) Centralized Stablecoins Backed by Fiat Reserves

These stablecoins maintain a 1:1 fixed exchange rate with fiat currencies such as the US dollar or euro. Issuers typically hold equivalent reserves in bank accounts to ensure the stablecoin's value. For example, Tether (USDT) and USD Coin (USDC) are representative examples issued by centralized entities. USDT has the highest liquidity, with a market capitalization exceeding $92 billion.

(2) Decentralized Stablecoins Collateralized by Cryptocurrencies

These stablecoins are decentralized and built using innovative blockchain-based protocols, offering enhanced security and transparency. Also known as collateralized stablecoins, their backing comes from other cryptocurrencies such as Ethereum or Bitcoin to maintain price stability. DAI by MakerDAO is a typical example, generated through an over-collateralization mechanism and widely adopted across DeFi protocols.

(3) Decentralized Algorithmic Stablecoins

A type of decentralized stablecoin whose value is automatically adjusted via algorithms without requiring collateral. It relies on market supply and demand dynamics to maintain a fixed price. Ampleforth is an algorithmic stablecoin utilizing an elastic supply mechanism that automatically adjusts its supply based on market demand.

(4) Hybrid-Mechanism Stablecoins

These stablecoins combine features from the above mechanisms to achieve greater price stability. For instance, Frax integrates both algorithmic control and fiat reserves through a hybrid model—partially backed by fiat reserves and partially managing supply algorithmically to maintain price stability.

In summary:

Centralized stablecoins solve the problem of anchoring digital asset values by linking them to real-world assets such as the US dollar or gold, stabilizing their value while addressing deposit and withdrawal issues under regulatory frameworks. This provides users with more reliable ways to store and transact digital assets. However, they usually depend on centralized institutions for issuance and management, exposing them to risks related to issuer audits and regulatory oversight.

Decentralized stablecoins offer a freer and more transparent development path for the cryptocurrency market by leveraging verifiable smart contracts to build trust. However, they also face challenges such as hacking threats and governance risks.

II. On-Chain Data Analysis

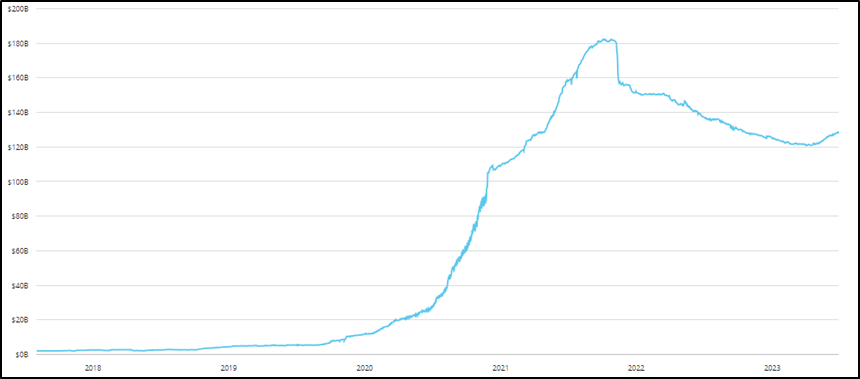

Since Tether launched the first stablecoin USDT in 2014, various types of stablecoins have emerged, including USDC, DAI, and BUSD. The total market cap of stablecoins gradually increased starting in 2018, began rising sharply from mid-2020, and peaked on April 7, 2022, reaching $182.65 billion. Subsequently, the market trend declined, and as of December 28, 2023, the total market cap had fallen to $128.77 billion.

Figure: Stablecoin Market Cap (2018.2.1 – 2023.12.28)

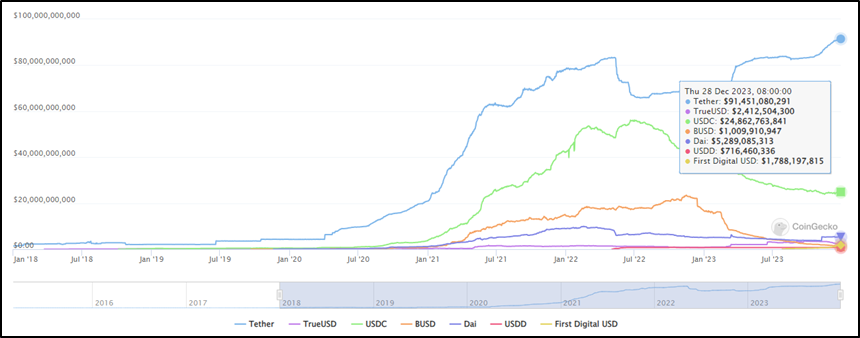

Figure: Top Stablecoins Market Cap (2018.1.1 – 2023.12.28)

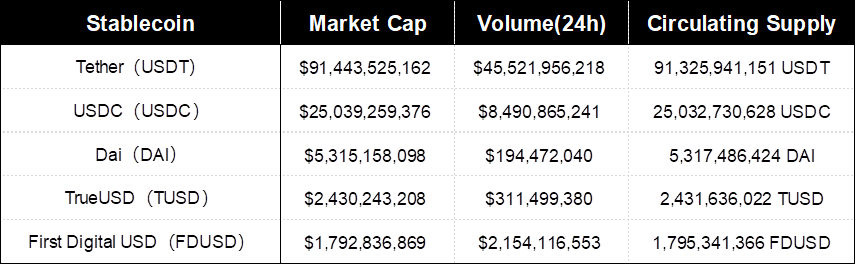

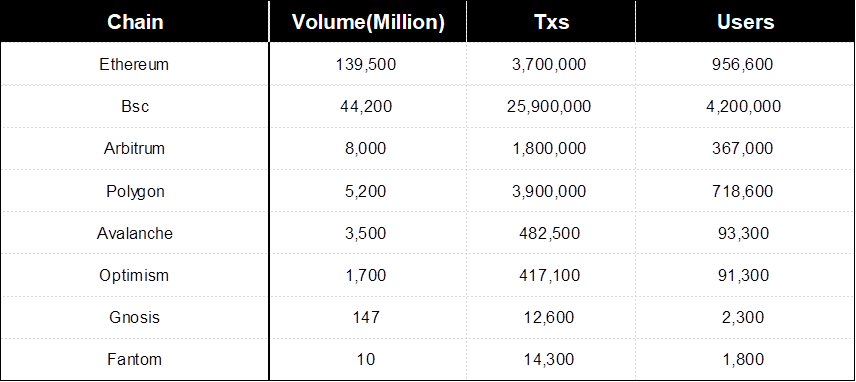

In terms of market share, USDT has consistently maintained its leading position. Since early 2020, the top five stablecoins by market cap have been USDT, USDC, BUSD, DAI, and TrueUSD. However, by June 2023, due to sanctions against Binance, BUSD’s market cap dropped significantly and it gradually lost its place among the top five. Meanwhile, First Digital USD (FDUSD), launched on June 1, 2023, experienced rapid growth and surpassed BUSD in market cap by December 14, becoming the fifth-largest stablecoin. Below are key statistics including market cap, trading volume, circulating supply, and user count for the top five stablecoins:

Figure: TOP 5 Stablecoins' Market Cap, Volume, and Circulating Supply. Data as of 2023/12/28

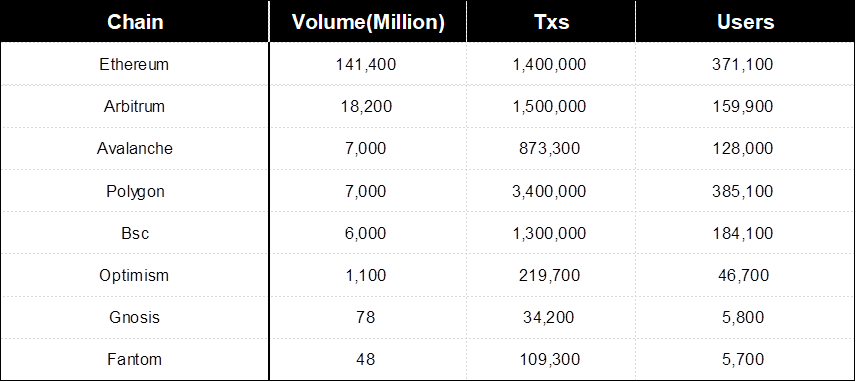

Figure: USDT’s Transaction Volume, Number of Transactions, and User Count Over the Past 30 Days, data as of 2023/12/28

Figure: USDC’s Transaction Volume, Number of Transactions, and User Count Over the Past 30 Days, data as of 2023/12/28

Figure: DAI’s Transaction Volume, Number of Transactions, and User Count Over the Past 30 Days, data as of 2023/12/28

III. Security and Risks of Algorithmic Stablecoins

Algorithmic stablecoins operate similarly to shadow banking systems. Unlike traditional stablecoins, they do not rely on centralized institutions to maintain stability but instead use algorithms to adjust market supply and demand to keep prices within a target range. However, this form of currency faces several challenges, including insufficient market liquidity and exposure to black swan events. The value of algorithmic stablecoins is not fully backed by external reserves but rather regulated through algorithm-driven market mechanisms to maintain price stability.

In recent years, algorithmic stablecoins have frequently collapsed due to death spiral issues, primarily manifested in the following aspects:

(1) Imbalance of Supply and Demand

When market demand for an algorithmic stablecoin declines, its price may fall below the target value, forcing the issuer to destroy or repurchase part of the circulating supply to restore balance. This could further erode market confidence and demand, triggering a vicious cycle of bank runs. The collapse of Luna/UST is the most prominent example.

(2) Governance Risks

Since algorithmic stablecoins rely on smart contracts and community consensus, they are exposed to governance risks such as code vulnerabilities, hacker attacks, and price manipulation.

(3) Legal and Regulatory Challenges

Because algorithmic stablecoins lack tangible assets as collateral or anchor points, they face heightened legal and regulatory scrutiny and uncertainty. More countries and regions are expected to restrict or ban the use of algorithmic stablecoins in the future.

(4) Case Study: Collapse of Luna/UST

Business Model: Algorithmic Stablecoin (UST/Luna) and High Yield (Anchor):

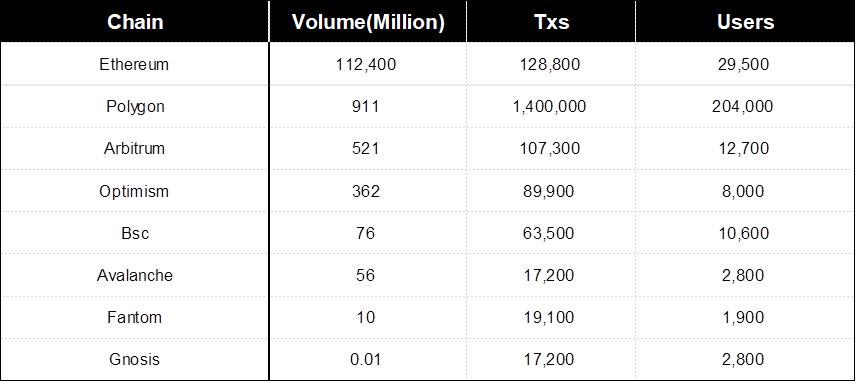

The core design of the Terra ecosystem focused on expanding the usage scenarios and payment demand for the UST stablecoin. UST operated using a dual-token model: Luna served as the governance, staking, and validation token, while UST was the native USD-pegged stablecoin. In simple terms, each time a UST was minted, $1 worth of Luna had to be burned. The arbitrage mechanism helped maintain the UST-dollar peg: if $UST traded above $1, users could burn $1 worth of Luna to mint one UST and profit from the price difference; if $UST fell below $1, users could burn one UST to receive $1 worth of Luna, then sell the Luna for profit.

Anchor Protocol (hereinafter "Anchor") was a DeFi platform officially launched by Terra in March 2021, essentially functioning as a lending protocol similar to Compound. What made Anchor unique was its exceptionally high APY (Annual Percentage Yield), consistently around 20%. Driven by these high yields, demand for UST surged, forming the core of UST’s business model. Within the Terra ecosystem, Anchor acted as a “state-owned bank,” promising ultra-high 20% annual returns to attract public deposits in the form of UST.

Revenue Model: Expenses Exceeding Income, Planting Hidden Dangers:

Anchor’s main revenue came from loan interest, PoS rewards on collateral (currently bLUNA and bETH), and liquidation penalties. Its primary expense was the ~20% annual yield paid to depositors. Additionally, Anchor provided substantial ANC token subsidies to borrowers and incurred extra costs to stabilize the ANC token price, mitigating downward selling pressure.

This constitutes the UST and Luna revenue-expenditure model. Based on current UST and Luna volumes, Terra needed to cover approximately one billion dollars in annual operating costs—clearly unsustainable for Anchor alone. Thus, in February 2022, as Anchor’s reserve pool neared depletion, LFG announced a $450 million UST allocation to replenish it. This confirmed that Anchor differed from other lending protocols—it was not designed for profitability but rather functioned as a subsidized product funded by Terra to drive UST adoption and expansion.

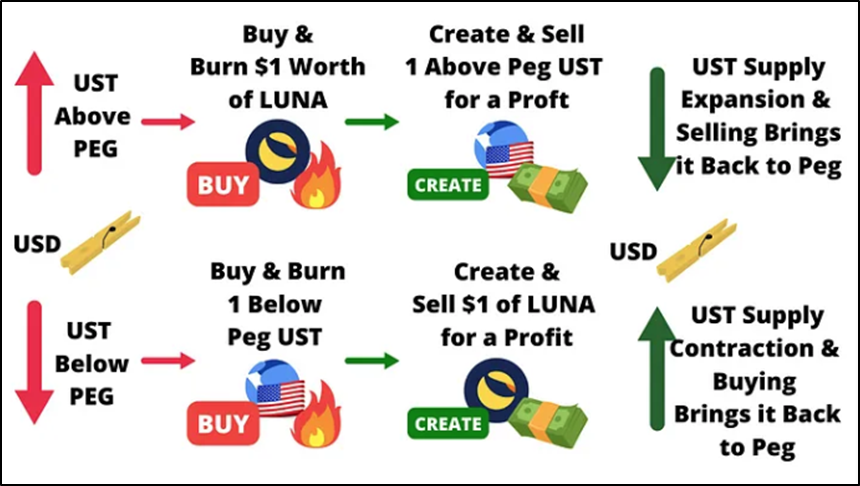

The Emergence of a Death Spiral:

From the above analysis, Terra’s full logic becomes clear: Anchor created artificial demand scenarios to stimulate UST demand; rising demand drove UST minting and attracted new users; increasing participation improved ecosystem metrics (TVL, addresses, number of projects, etc.), gradually pushing up Luna’s price; project teams or foundations then cashed out Luna to fund subsidies maintaining high yields—an endless loop.

If this cycle remained stable, UST would act as the engine and Luna as the stabilizer. With growing Web3 projects and users, the two would reinforce each other positively during bullish trends, creating a virtuous spiral.

However, when Luna’s market cap relative to the stablecoin decreases and trading depth shrinks, collateral becomes insufficient, de-pegging risk increases, and the cost of maintaining consensus rises—leading to a death spiral. For example, when the overall market crashes and Luna follows suit, or when coordinated attacks target Luna’s price, a death spiral can occur.

How high is the threshold for triggering a death spiral, and how great is the risk?

Project teams certainly recognize the importance of sustaining the cycle and subsidy sources and have taken measures to increase reserve holdings. Anchor is adding new collateral assets—bLuna, bETH, wasAVAX, bATOM—which will help boost profits. The introduction of dynamic anchor rates means, per proposal, the yield will decrease by 1.5% monthly, with a minimum APY of 15%, to be reached within three months. But if Anchor’s APY falls below investor expectations, demand for UST and Luna will decline, reducing UST demand and requiring more Luna to be minted, thereby driving down Luna’s price.

Therefore, a death spiral may be triggered by broad market downturns, declining Anchor APY, or targeted attacks on Luna’s price. Currently, the occurrence of Terra’s death spiral appears almost inevitable.

IV. Analysis of Black and Gray Crypto Activities

“Black and gray industries” typically refer to illegal or socially harmful industrial chains involving fraud, illicit trading, smuggling, and other unlawful activities. In recent years, these sectors have increasingly exploited cryptocurrencies—especially stablecoins like USDT—for illegal fundraising and money laundering. The emergence of “black U” (illicit USDT) severely undermines the secure development of the stablecoin ecosystem. Key areas include:

(1) Online Gambling

Online gambling is a particularly harmful segment of the black and gray economy, involving operations of online gambling platforms, network technologies, payment systems, and advertising. Illicit actors create seemingly legitimate gambling websites or apps to attract users, promoting them through malicious ads, spam emails, and other methods to expand their user base. Cryptocurrencies are commonly used as payment methods due to their relative anonymity, making online gambling harder to trace. Before committing crimes, bad actors often create or purchase fake identities—or blockchain addresses in the crypto context—and use gambling platforms to launder funds and conceal illegal proceeds.

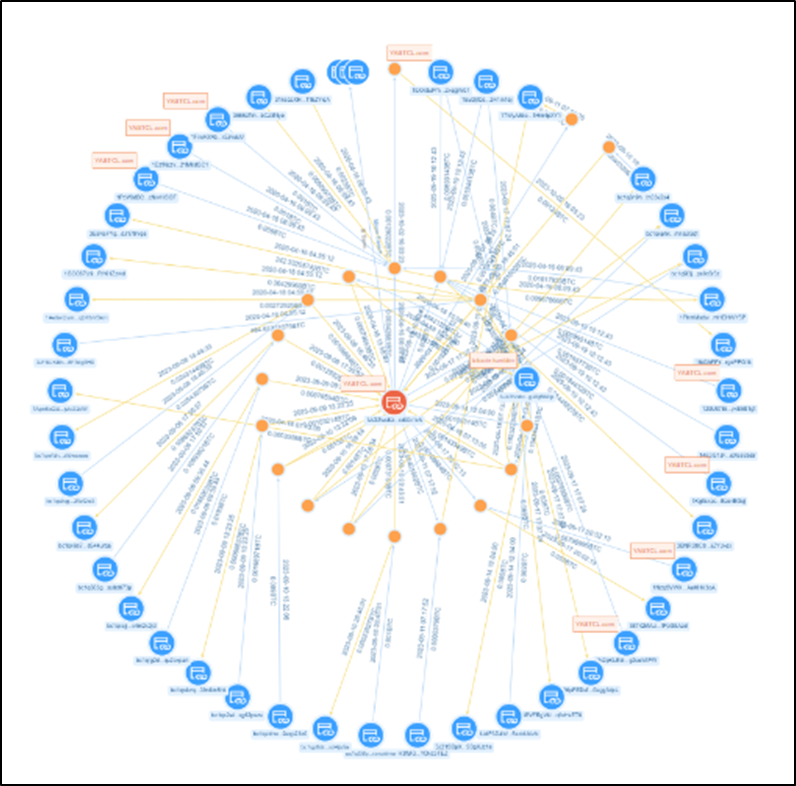

Figure: Transaction Graph Analysis of a Gambling Address 1AGZws…x1cN

(2) “Money Running” Platforms

“Money running” typically refers to artificially inflating scores in software or hardware performance tests. Black-market USDT “money running” scams pose as money laundering services, claiming to clean illicit USDT funds. In reality, these are investment fraud schemes. Once participants deposit large amounts of USDT, the platform refuses to return funds under various pretexts.

(3) Ransomware

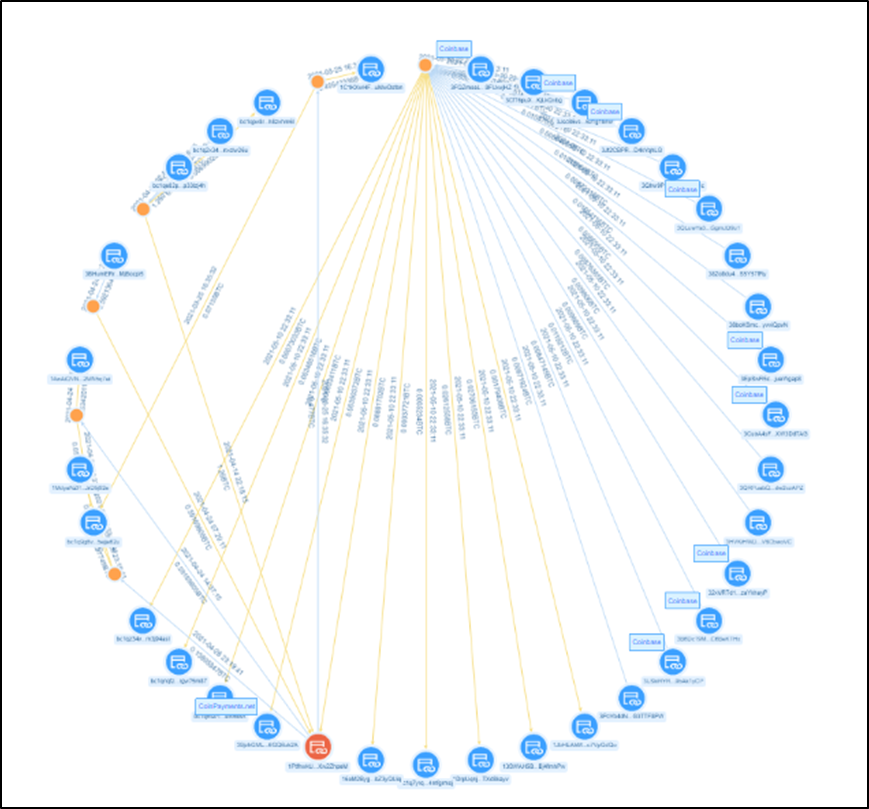

Ransomware attacks remain a serious cybersecurity threat today. They often spread via phishing emails or malicious links, combined with social engineering tactics to trick users into clicking and downloading malware. After encrypting victims’ data, ransomware displays a ransom note demanding payment for decryption keys—usually in cryptocurrency (e.g., Bitcoin) to enhance payment anonymity. Given that financial institutions and critical infrastructure manage vast amounts of sensitive data, they are prime targets. In November 2023, ICBC Financial Services (ICBCFS), a wholly owned subsidiary of Industrial and Commercial Bank of China in the U.S., suffered a LockBit ransomware attack, causing significant damage. Below is the on-chain transaction hash graph of a LockBit ransom collection address.

Figure: On-Chain Transaction Hash Graph of a LockBit Ransom Collection Address

(4) Terrorism Financing

Terrorist organizations exploit cryptocurrencies’ anonymity and decentralization to raise and launder funds, evading monitoring by traditional financial institutions and law enforcement. Fundraising, fund transfers, and cyberattacks are common ways terrorists may leverage cryptocurrencies. For example, Ukraine has used crypto for fundraising, and Russia has used it to circumvent SWIFT sanctions. In October 2023, Tether (USDT) froze 32 addresses linked to terrorism and war activities in Israel and Ukraine, which collectively held 873,118.34 USDT.

(5) Money Laundering

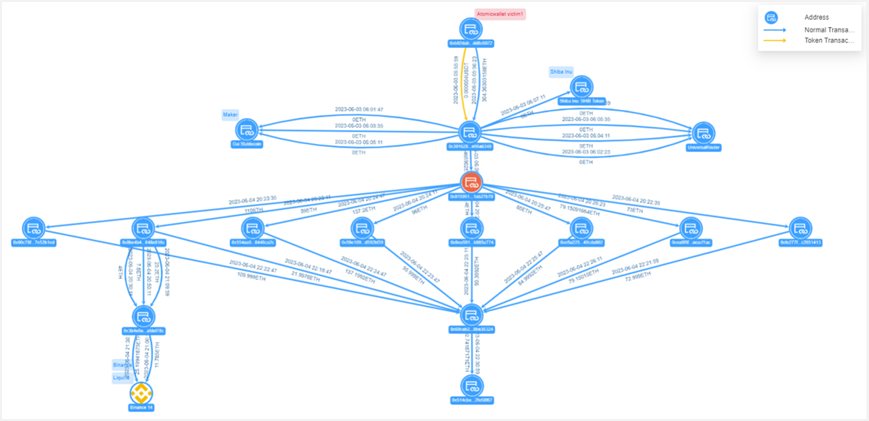

Due to the anonymity and traceability challenges of cryptocurrencies, they are frequently exploited for money laundering. Statistics and on-chain risk labels indicate that over half of blacklisted USDT assets are associated with black and gray industries, mostly used for money laundering. Take the North Korean hacking group Lazarus Group as an example—they have successfully transferred and laundered over $1 billion in recent years. Their typical laundering patterns include:

Splitting funds across multiple accounts and conducting numerous small-value transfers to increase tracking difficulty.

Creating large volumes of fake coin transactions to obscure trails. In the Atomic Wallet incident, 23 out of 27 intermediary addresses were used solely for fake transfers. Similar techniques were recently observed in the Stake.com breach analysis. Earlier incidents like Ronin Network and Harmony did not employ such interference, indicating Lazarus Group’s laundering tactics are evolving.

Increasing use of on-chain mixing tools (e.g., Tornado Cash). Previously, Lazarus frequently relied on centralized exchanges for initial funding or OTC trades, but recently avoids them—likely due to recent sanction-related incidents.

Figure: Fund Transfer View from Atomic Wallet Incident

As the use of cryptocurrencies in black and gray industries and other illicit activities continues to grow, regulating crypto—and especially stablecoins—becomes increasingly critical.

V. Stablecoin Regulation

Centralized stablecoins are issued and managed by centralized entities, so issuers must possess sufficient strength and credibility. To ensure transparency and trustworthiness, issuing institutions should register, file reports, undergo supervision, and be audited by regulators. Moreover, stablecoin issuers must maintain a stable exchange ratio with fiat currencies and disclose relevant information promptly. Regulators should mandate regular audits to ensure the safety and adequacy of reserve funds. Additionally, risk monitoring and early-warning mechanisms should be established to identify and respond to potential risks promptly.

Decentralized stablecoins use algorithms to adjust money supply and determine prices based on supply and demand, offering higher transparency but posing greater regulatory challenges. Key difficulties include auditing algorithmic flaws, mitigating risks in extreme scenarios, and defining how regulators can engage with community governance.

In 2019, Libra’s proposed launch drew global attention to stablecoins, revealing associated financial risks. The October 2019 report *Global Stablecoin Assessment* formally introduced the concept of global stablecoins and highlighted their potential impacts on financial stability, monetary sovereignty, and consumer protection.

Subsequently, the G20 tasked the Financial Stability Board (FSB) with reviewing the Libra project, resulting in two sets of regulatory recommendations released in April 2020 and February 2021. Under FSB guidance, several countries and regions developed their own stablecoin regulations. Some nations have intensified oversight—for example, the U.S. draft *Stablecoin Payments Act*, Hong Kong and Singapore’s regulatory policies, and the EU’s *Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation* (MiCA).

The U.S. regulatory draft *Stablecoin Payments Act*, released in April 2023, outlines conditions for issuing payment stablecoins. It emphasizes a 1:1 peg with fiat or highly liquid assets, requires issuers to apply for Federal Reserve approval within 90 days, mandates audits and reporting, and grants the Federal Reserve emergency intervention and penalty powers. This bill reflects both the U.S. government’s focus on the stablecoin market and its support for crypto innovation.

In January 2023, the Hong Kong government discussed cryptocurrency regulation and published a summary, emphasizing bringing crypto activities under supervision, defining regulatory scope and requirements, advocating differentiated regulation, and stressing coordination with international bodies and jurisdictions.

Singapore released conclusions from its consultation on a stablecoin regulatory framework in August 2023. It revised rules on historical scope, reserve management, capital requirements, and disclosure to finalize the framework with emphasis on differentiated regulation. It also updated the *Payment Services Act* and related regulations to strengthen coordination with international regulators.

The Council of the European Union, composed of ministers from 27 EU member states, approved MiCA in May 2023. Originally proposed by the European Commission in 2020, MiCA will take effect in 2024. It covers three main areas: (1) rules for crypto asset issuance, imposing complex requirements on issuers regarding authorization, governance, and prudential standards; (2) crypto asset service providers (CASP), who must obtain authorization from national authorities and comply with financial company regulations under MiFID II; and (3) rules to prevent market abuse in crypto markets.

The United States currently leads in crypto regulation, with its *Stablecoin Payments Act* potentially becoming the world’s first formal legislation dedicated to stablecoins. Policies in regions like Hong Kong and Singapore require time to mature into formal laws. There are differences in stablecoin regulation across jurisdictions, with legislative progress at varying stages. Relevant institutions and operators should continuously assess risks and adapt their business models to comply with applicable laws and avoid potential compliance pitfalls.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News