Stanford Blockchain Club: Zero-Knowledge Proofs Have Their Own Moore's Law—Proofs Generated Per Second Double Annually

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Stanford Blockchain Club: Zero-Knowledge Proofs Have Their Own Moore's Law—Proofs Generated Per Second Double Annually

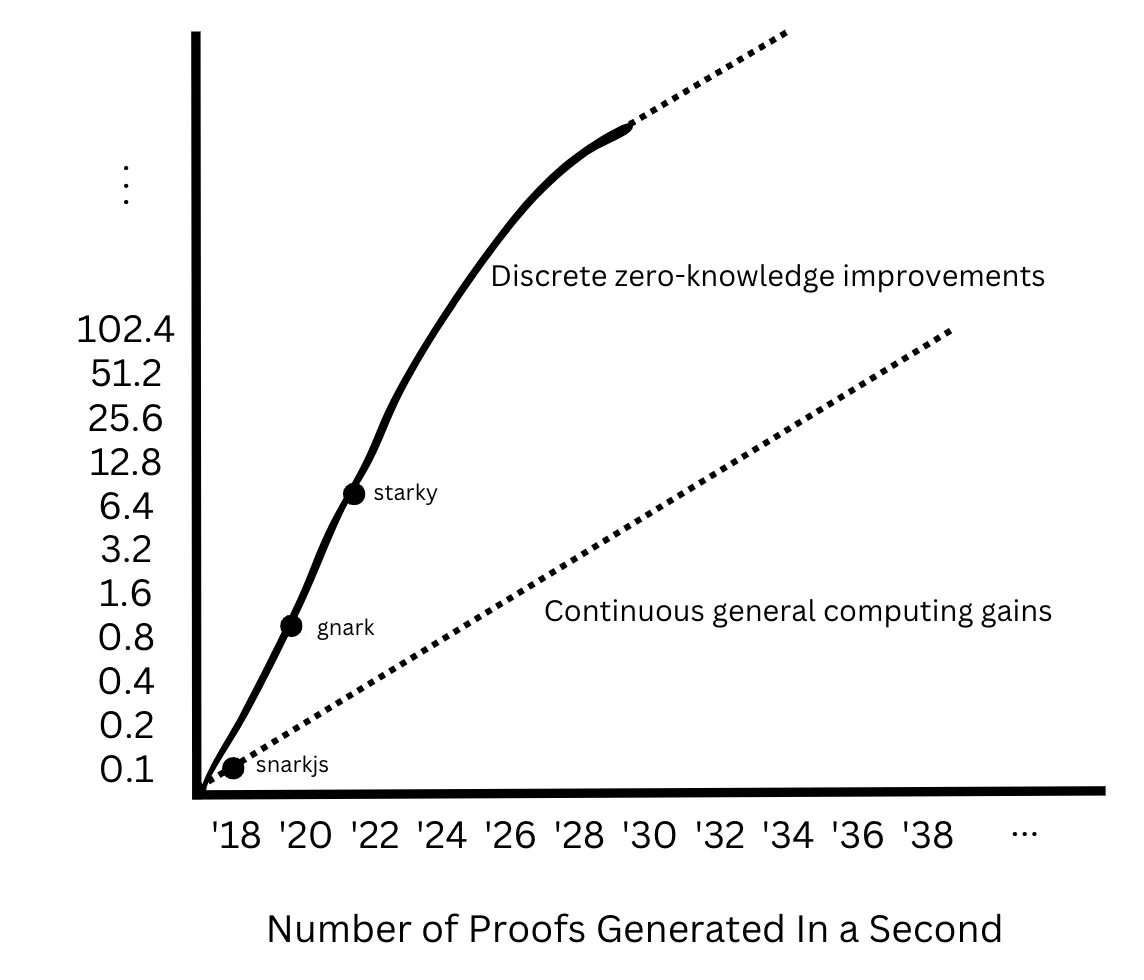

In the coming years, the number of proofs generated per second will more than double, then asymptotically approach the underlying gains of general-purpose computing.

Authored by: STANFORD BLOCKCHAIN CLUB, ROY LU

Translated by: TechFlow

Note: This article is sourced from the Stanford Blockchain Review. TechFlow is an official partner of the Stanford Blockchain Review and has been granted exclusive authorization to translate and republish this content.

Introduction

In this article, we will explore how zero-knowledge proofs can transform our lives beyond Web3. I will discuss levers for performance improvement, propose a "Moore's Law for zero-knowledge," and identify patterns of value accumulation.

Zero-knowledge (ZK) is one of the most transformative technologies in today’s Web3 landscape, with immense potential in scalability, authentication, privacy, and more. However, current performance levels limit its applicability across many use cases. As ZK technology matures, I believe it will grow exponentially, finding widespread adoption not only in Web3 but also in traditional industries. Just as Moore's Law predicted that transistor density on chips would double every two years, I now propose a similar exponential law for zero-knowledge proofs—specifically:

In the coming years, the number of proofs generated per second will more than double annually, gradually approaching the gains of underlying general-purpose computing.

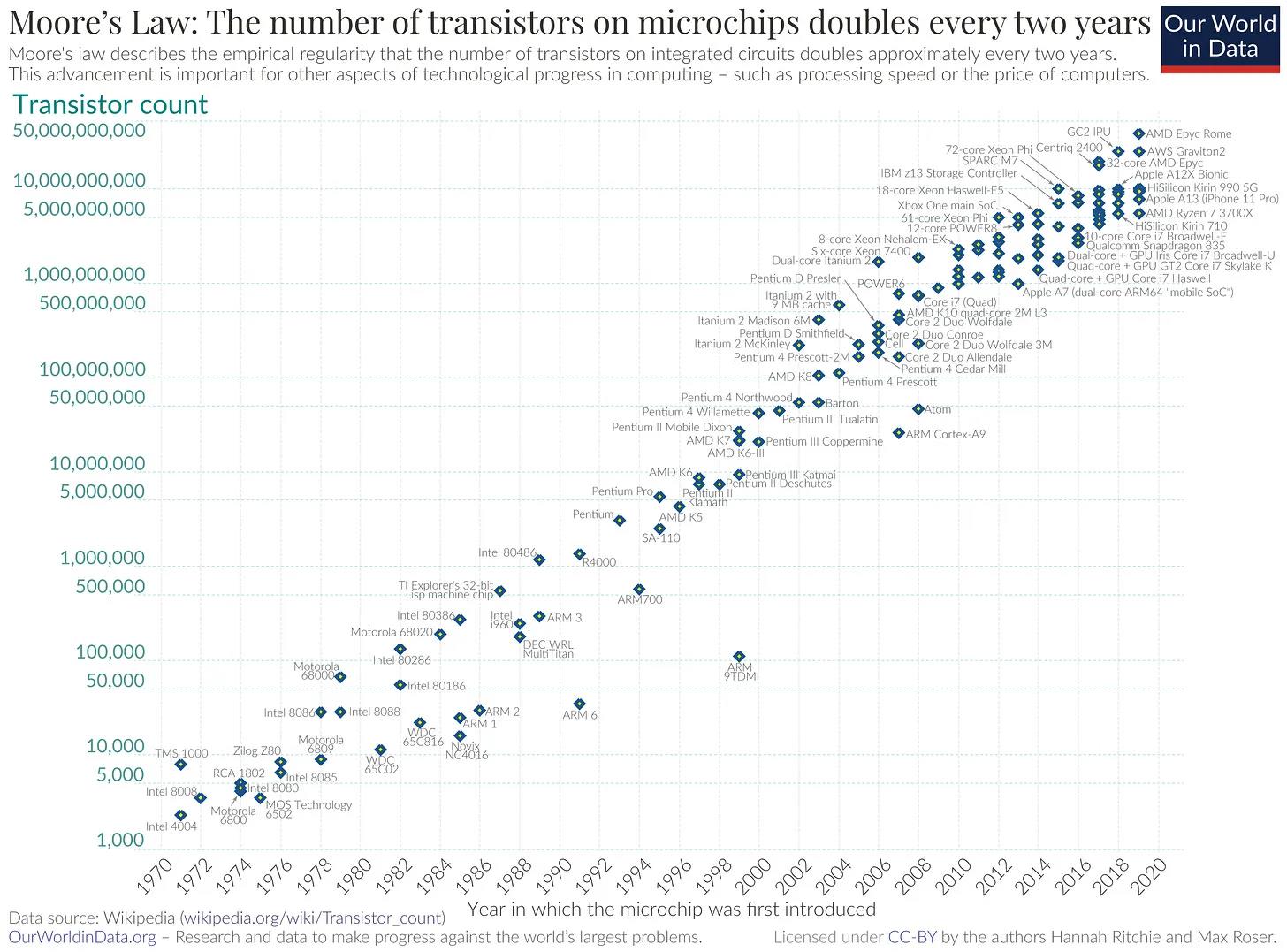

Overview of Moore's Law

Moore's Law, proposed in 1965 by Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel, predicted that “the complexity of semiconductor integrated circuits would double every two years.” Over the past 58 years, Moore’s Law has driven mobile computing, machine learning, and nearly every aspect of our digital lives, fundamentally changing how we interact with technology.

Gordon Moore empirically observed that as the number of transistors on a chip doubled, manufacturing costs remained largely unchanged due to economies of scale. He further noted that demand for computational power would drive investment into increasing transistor density.

As computing power increased exponentially on smaller and smaller chips, this quantitative leap in transistor count led to qualitative changes in how we use and interact with computers.

Our smartphones—more powerful than the Apollo 11 computer—fit conveniently in our pockets, enabling us to stream content from any website and communicate with anyone around the world. The training of large language models paved the way for ChatGPT, transforming how we interact with information from data retrieval to intelligent synthesis.

The Explosion of Zero-Knowledge Proofs and Web3

Just as the doubling of transistors and Moore’s Law qualitatively transformed our interaction with modern technology, the exponential growth of zero-knowledge proofs will unlock a new wave of application-layer experiences. At their core, ZK proofs enable privacy, verifiable correctness, and scalability—properties rooted in private computation, provable correctness, and recursive succinctness. These represent a fundamental shift toward a new computing paradigm.

Private Computation

Zero-knowledge enables computation over private data modules, sharing only results externally for verification. A real-world example: if banks adopted ZK-based computation, identity theft could be prevented. For instance, users could allow loan approval programs to run over their identity and credit history without revealing sensitive data—their privacy remains protected. In Web3, ZK powers fully private Layer 1 networks like Aleo and Mina, or private payment networks such as Zcash, zk.money, Elusiv, and Nocturne. ZKPs also allow teams like Renegade to operate dark pools, listing trade orders without impacting market prices. Value is transferred without exposing users’ private data.

Provable Correctness

For opaque computations, zero-knowledge provides provenance for inputs, outputs, and processing. An example is decentralized machine learning via a network of remote compute nodes, democratizing access to AI. ZKPs can prove the data, weights, and training rounds used in ML models, verifying that the entire training process proceeded as intended—correctness is established. In Web3, teams like Gensyn and Modulus Labs are already implementing zkML, while general-purpose ZKVMs like Risc Zero are being developed. To verify cross-chain state correctness, ZKPs are used in ZK bridges such as Polymer, Succinct Labs, Herodotus, and Lagrange. ZK also enables applications like Proven to demonstrate reserve accuracy.

Recursive Succinctness

ZK can also fold multiple proofs into a single one. Another real-world example is authenticity tracking in supply chains. Each manufacturer at every step of the chain can use ZKPs to prove product authenticity without disclosing sensitive production details. These ZKPs are then recursively proven, generating a final ZKP that verifies the integrity of the entire supply chain—scalability is achieved. In Web3, thousands of transactions’ ZKPs can be merged into a single proof, powering L2 networks like Starkware, Scroll, and zkSync, dramatically increasing blockchain throughput.

Defining Moore’s Law for Zero-Knowledge

From the above, we’ve seen the abstract similarity between transistors enabling application-layer explosions and ZKPs unlocking similar waves of innovation in Web3. It’s now time to derive a concrete definition of a “Moore’s Law for zero-knowledge” by comparing general-purpose computing and zero-knowledge computing.

General-Purpose Computing vs. Zero-Knowledge Computing

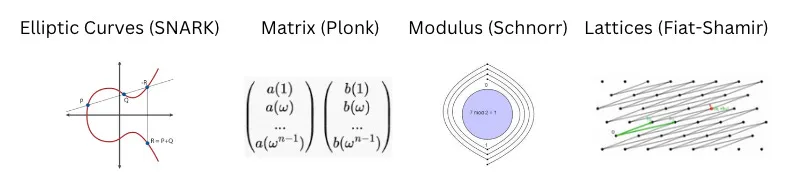

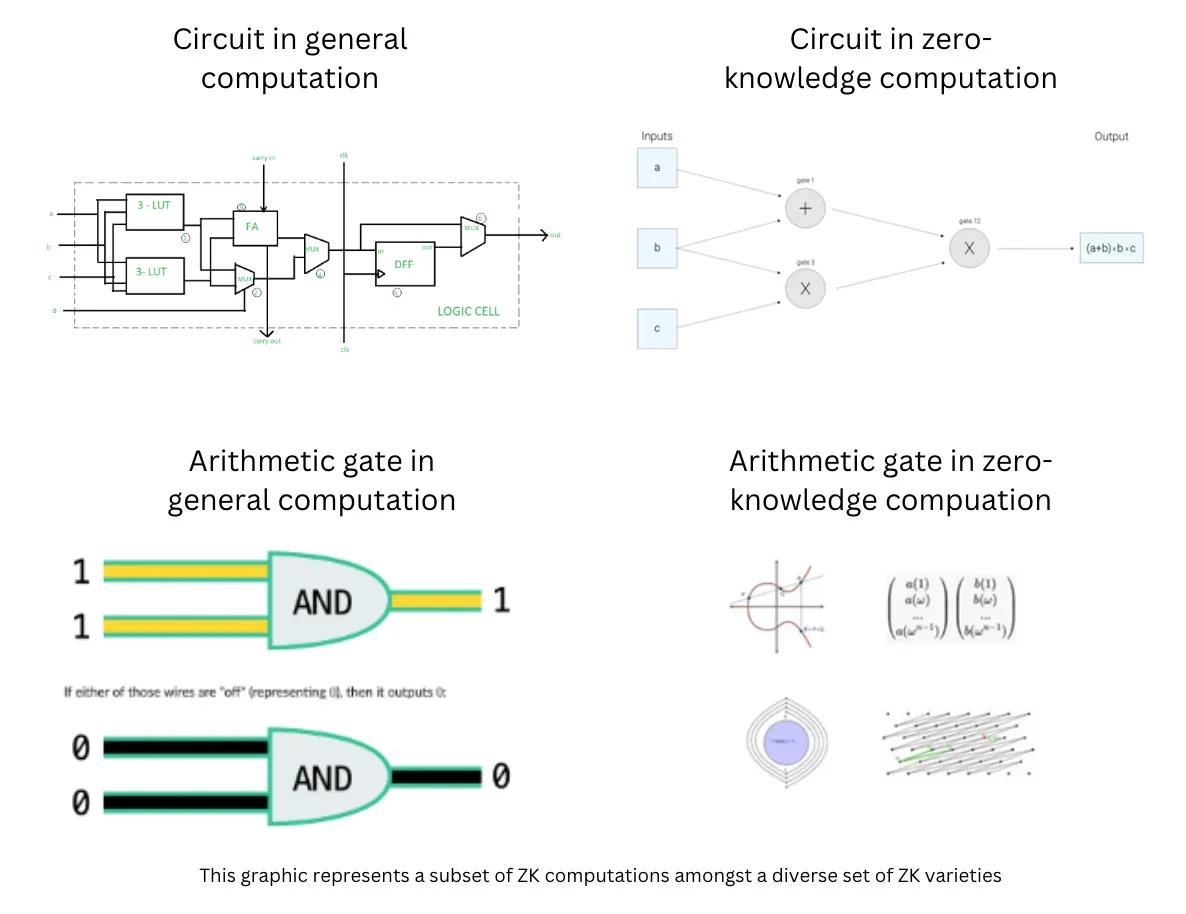

In general-purpose computing, logic gates are built from metal-oxide-silicon transistors. Each gate performs operations such as AND, OR, XOR, etc., collectively enabling program execution.

All else equal, zero-knowledge computing is more expensive than general-purpose computing. For example, “hashing 10KB with SHA2 using Groth16 takes 140 seconds, whereas without ZK it takes just milliseconds.” This is because ZK computations rely on complex arithmetic operations for each logical operation.

In zero-knowledge computing, operations are represented using finite fields. In SNARKs, each operation occurs on an elliptic curve. In other ZK variants, operations may involve matrices, lattices, or modular arithmetic—complex mathematical structures used for arithmetic operations. Even basic addition, subtraction, and multiplication become costly. Input data is converted into finite field elements rather than standard numbers. The complexity of these structures forms the basis of cryptographic security. While arithmetic details go beyond this article’s scope, the key point is that just as logic gates execute on physical circuits, zero-knowledge logic executes in software-defined circuits.

Thus, in general-purpose computing, performance improvements are governed by physical laws, whereas in zero-knowledge computing, they are governed by mathematical principles. We recognize that although hardware acceleration yields significant gains, when applying Moore’s Law to ZK, progress lies primarily in the software domain, not necessarily hardware. Based on these fundamentals, we can define what a specific Moore’s Law for zero-knowledge might look like.

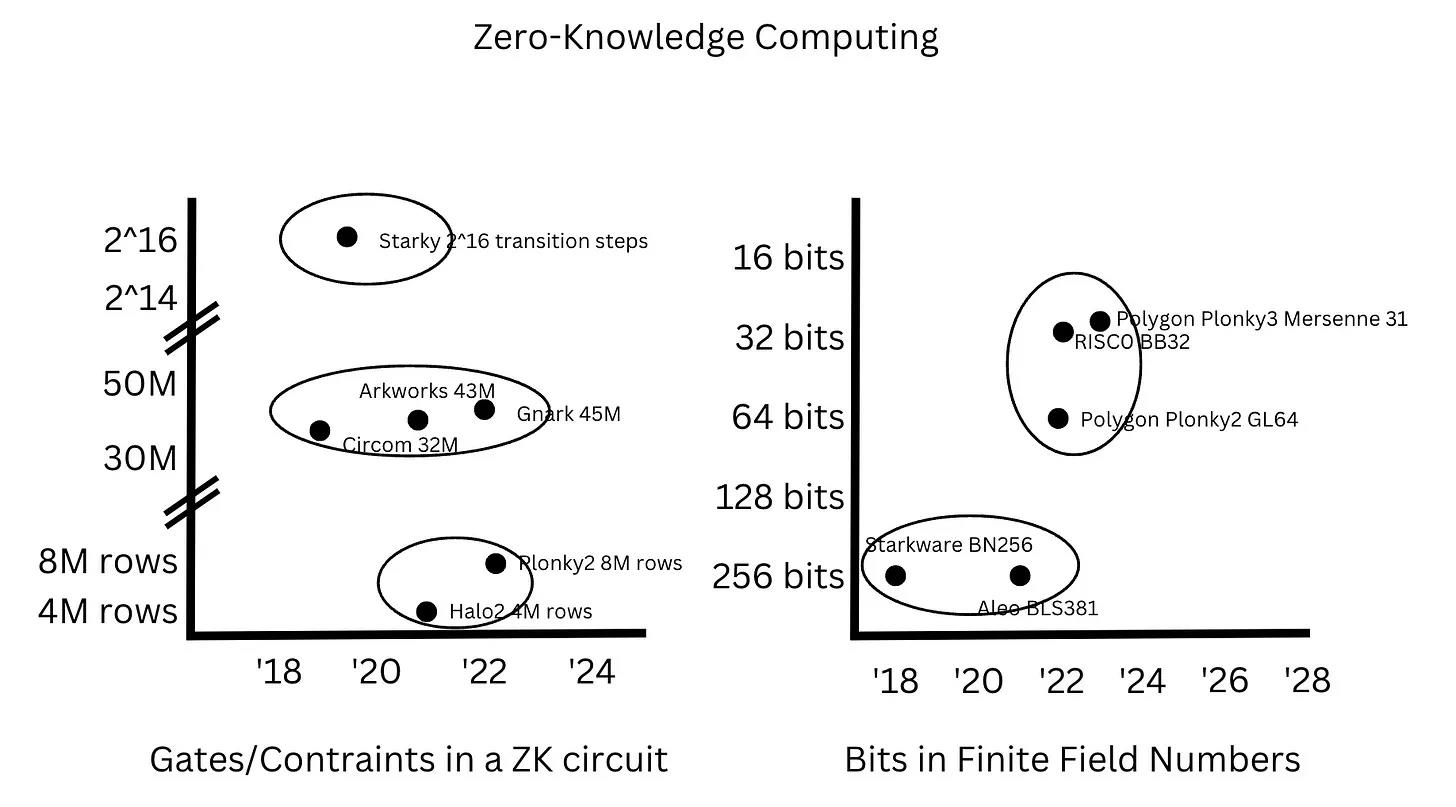

Breakthrough Improvements in Zero-Knowledge Are Discontinuous

Perhaps the most important observation is that while improvements in general-purpose computing are continuous, those in zero-knowledge computing occur in discrete steps.

Specifically, from 2005 to 2020, CPU core counts roughly doubled every five years, and clock frequencies also approximately doubled every five years from the 1990s to the 2010s. In contrast, constraint counts in ZK circuits did not improve continuously—they jumped from 30–40M constraints in SNARKs to 4–8M rows in PLONKs, then to 2^14–2^16 transition steps in STARKs. Similarly, bit lengths in finite fields remained around 256 bits from 2018 to 2022, then jumped to 32 bits between 2022 and 2023 to leverage 32-bit register efficiency.

Moreover, recent developments like HyperSpartan support customizable constraint systems (CCS), capable of capturing R1CS, Plonkish, and AIR without additional overhead. SuperNova builds upon Nova—a high-speed recursive proof system with folding schemes compatible with diverse instruction sets and constraint systems. These advances further expand the design space for ZK architectures.

Based on these observations, the fundamental Moore’s Law for zero-knowledge is not based on any single vector of continuous improvement, but rather on holistic performance gains in proof generation rates, driven by discontinuous leaps. I argue that before converging with gains in underlying general-purpose computing, Moore’s Law for ZK will proceed through discrete, revolutionary jumps:

In the coming years, the number of proofs generated per second will more than double annually, eventually asymptotically approaching the gains of underlying general-purpose computing.

Reducing the Cost of Zero-Knowledge Proofs

As previously mentioned, current zero-knowledge proofs are still too fragile and expensive for broad adoption across potential applications. In particular, verification costs far exceed proof generation costs. Rough estimates suggest proof generation costs less than $1, based on two facts: 1) On Amazon AWS, an EC2 instance with 16 CPUs and 32GB RAM costs $0.4/hour, and decentralized compute nodes are expected to be even cheaper; 2) Polygon Hermez incurs $4–6/hour to generate about 20 proofs per hour.

However, on-chain verification costs remain high, consuming 230,000 to 5 million gas per verification—roughly $100–$2,000 per verification. While ZK rollups benefit from economies of scale by amortizing costs across thousands of transactions, other types of ZK applications must find ways to reduce verification costs to enable the aforementioned application-layer innovations and deliver tangible quality-of-life improvements to end users.

Given that breakthroughs in ZK capacity may occur in discontinuous, discrete steps, let’s examine potential areas where such breakthroughs could emerge. Below are some optimization methods listed in zkPrize:

-

Algorithmic optimizations, including multi-scalar multiplication (MSM) and number-theoretic transforms (NTT), commonly used to accelerate elliptic curve cryptography and amenable to hardware acceleration. Fourier transforms, a form of NTT, have already been optimized across various implementations.

-

Parallel processing can increase ZK throughput by delegating parts of data preprocessing, circuit evaluation, or proof generation to multiple processing units or threads.

-

Compiler optimizations can improve register allocation, loop optimization, memory management, and instruction scheduling.

In algorithmic optimization, examples include the shift from R1CS in SNARKs to Plonkish in Halo2, Plonky2, and HyperPlonk—distinct from the AIR used in Starky proofs. Additionally, recent advances in folding schemes are exciting, as HyperNova supports incrementally verifiable computation with customizable constraint systems. In parallel processing, the Plonky2 recursive framework released by the Polygon team expands possibilities for parallel proof generation. In compiler optimization, leveraging LLVM for zero-knowledge is promising, as its intermediate representation (IR) can compile into instruction-set-agnostic opcodes. For example, Nil Foundation’s ZK-LLVM and Risc0’s zkVM both use LLVM to generate ZK proofs tracing every execution step. General-purpose ZKVMs or LLVM backends extend zero-knowledge beyond blockchains and enhance code portability for broader developer adoption.

Implications for Zero-Knowledge Builders

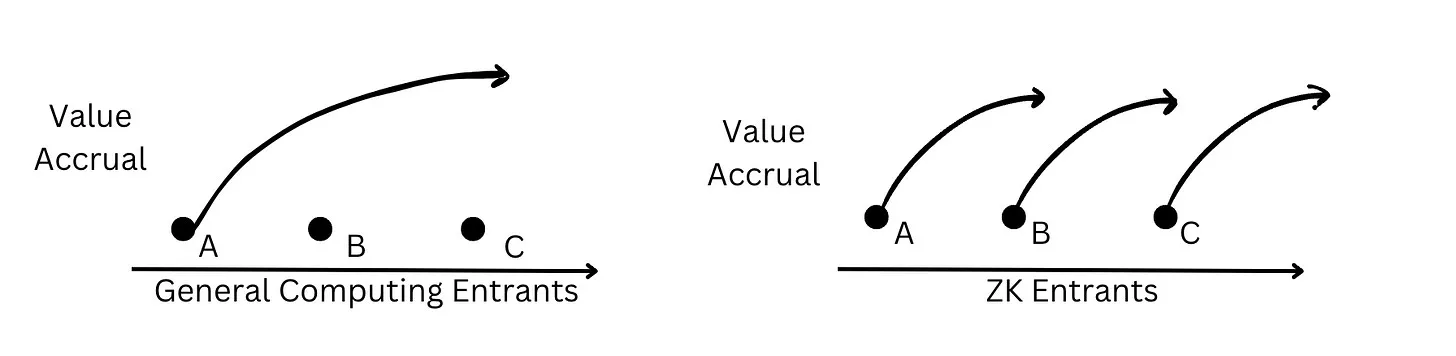

In general-purpose computing, value tends to accumulate among incumbents—for example, chip manufacturers benefit from moats formed around capital-intensive investments that support incremental improvements in fabrication processes for smaller chips. But because innovation in zero-knowledge occurs through discrete, revolutionary jumps, new teams still have ample opportunity to surpass existing players through research-driven technical breakthroughs, such as inventing novel proof systems.

Based on this theory, several implications follow for Web3 ZK builders:

-

ZK builders should adopt modular designs. Protocol developers working with ZK circuits should embrace modularity, allowing them to swap in state-of-the-art ZK components as they evolve.

-

Participants can benefit from research-driven disruption. Teams with strong research capabilities have the potential to pioneer revolutionary new proof systems and leapfrog existing players.

-

Vertical integrators can benefit from combining cutting-edge technologies. Since each layer of the ZK stack—from hardware to compilers to circuits—can undergo independent improvements, vertically integrated providers can modularly adopt the latest advancements and deliver state-of-the-art ZK tech to application teams at minimal cost.

Based on these insights, I anticipate three major industry developments:

-

New teams will surpass current ZK protocols through technological breakthroughs.

-

Existing protocols will seek moats based on ecosystems rather than technology.

-

Vertically integrated ZK providers will emerge, offering cutting-edge technology at lower costs. Innovation and disruption will thrive in this rapidly evolving field.

Conclusion

There is a paradox in technology: when technology works well, it becomes invisible. We don’t think about the cup when drinking water, just as we don’t notice the computer chip when sending an email. The easier a goal becomes to achieve, the more we overlook the process behind it.

Zero-knowledge proofs are already poised to deliver scalable applications with improved user experiences. When done well, we won’t notice the proofs themselves—but we’ll experience more private transactions, more accurate information, and faster, cheaper rollups. Thus, zero-knowledge proofs may ultimately become embedded in the foundation of our daily lives, much like transistors, microchips, and now artificial intelligence have seamlessly integrated into our routines.

We won’t need to consciously consider how ZK prevents election fraud, reduces transaction costs by disintermediating financial systems, or democratizes AI training via decentralized ZK computation. Perhaps one day, just as we took Moore’s observation—that “the number of transistors on a circuit board doubles every 18–24 months”—for granted as a so-called “law,” we will similarly accept that “the number of zero-knowledge proofs per second grows exponentially each year” as a given, enjoying the fruits of these innovations. When achieving goals becomes effortless, no one will constantly praise zero-knowledge—we’ll simply carry on with our lives.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News