Sora's Computing Power Math Problem

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

Sora's Computing Power Math Problem

Sora not only represents a significant advancement in video generation quality and capabilities, but also signals a potential substantial increase in GPU demand for inference tasks in the future.

Author: Matthias Plappert

Translation: Siqi, Lavida, Tianyi

Last month, OpenAI launched its video generation model Sora. Just yesterday, the company released a series of creative works produced by artists using Sora—results that are nothing short of stunning. Undoubtedly, in terms of generation quality, Sora is the most powerful video generation model to date. Its emergence will not only directly impact the creative industry but also influence solutions to key challenges in robotics and autonomous driving.

Although OpenAI published a technical report on Sora, it reveals extremely limited technical details. This article compiles research from Matthias Plappert at Factorial Fund. Matthias previously worked at OpenAI and contributed to the Codex project. In this analysis, he explores Sora’s key technical components, its innovative aspects, potential impacts, and examines the computational demands of video generation models like Sora. Matthias argues that as video generation becomes increasingly widespread, inference computing requirements will rapidly surpass those of training—especially for diffusion-based models like Sora.

According to Matthias’s estimates, Sora requires several times more compute during training than large language models (LLMs), roughly needing 4,200–10,500 Nvidia H100 GPUs trained for one month. Moreover, once the model generates between 15.3 million and 38.1 million minutes of video, the computational cost of inference will quickly exceed that of training. For comparison, users currently upload 17 million minutes of video daily to TikTok and 43 million minutes to YouTube. OpenAI CTO Mira recently noted in an interview that the high cost of video generation is precisely why Sora has not yet been made publicly available. OpenAI aims to achieve cost efficiency comparable to DALL·E's image generation before opening access.

OpenAI’s recently released Sora has amazed the world with its highly realistic video scene generation capabilities. In this article, we delve into the technical details behind Sora, examine the potential implications of such video models, and share our current reflections. Finally, we estimate the computational power required to train a model like Sora and compare training versus inference computing predictions—an analysis crucial for forecasting future GPU demand.

Key Takeaways

The core conclusions of this report are as follows:

-

Sora is a diffusion model based on DiT (Diffusion Transformer) and Latent Diffusion, scaled up significantly in both model size and training dataset;

-

Sora demonstrates the importance of scaling in video models, with continued scaling serving as the primary driver of capability improvements—similar to LLMs;

-

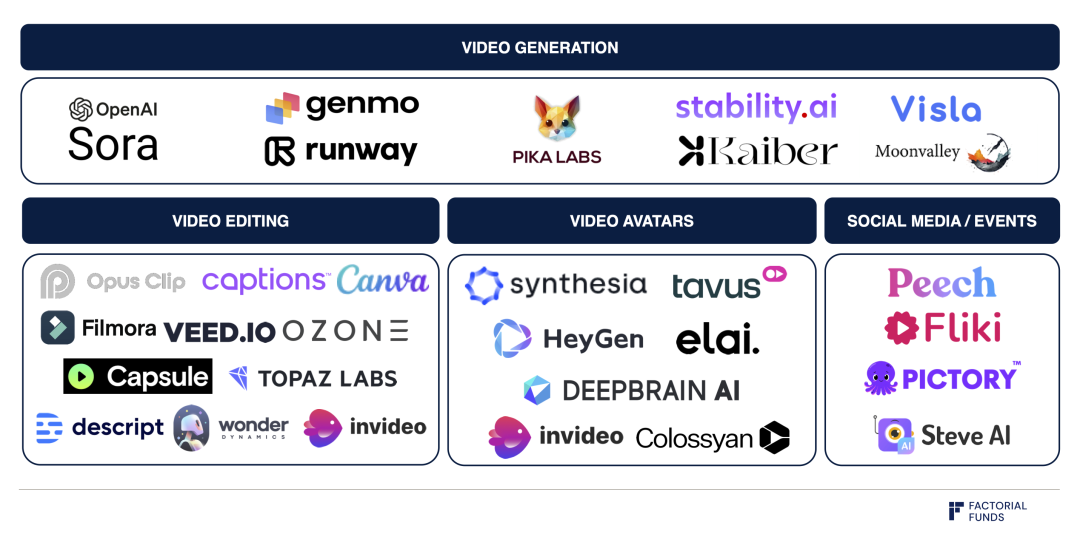

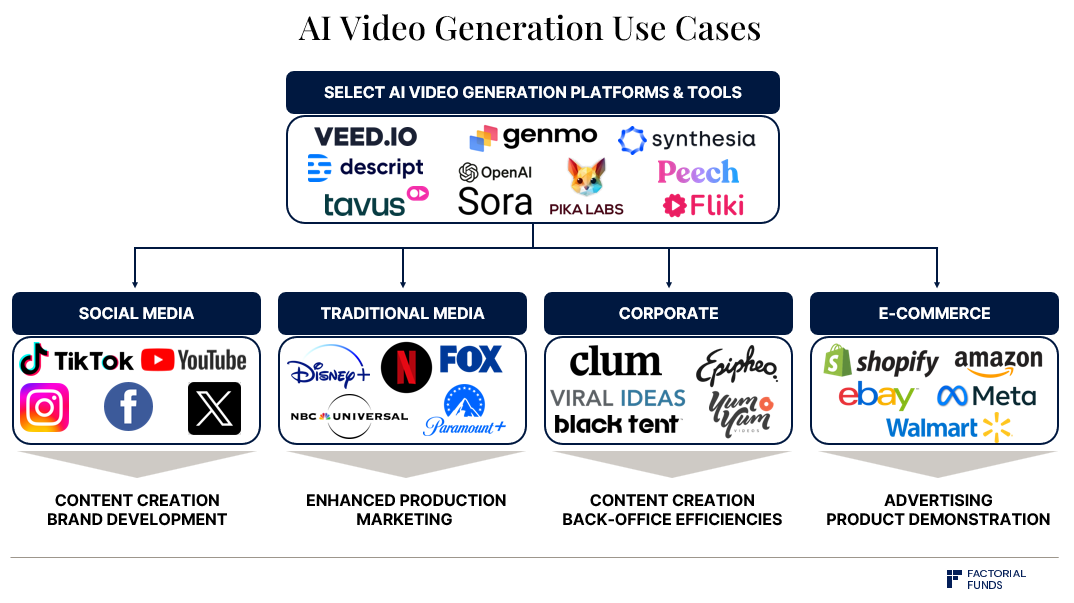

Companies like Runway, Genmo, and Pika are actively building intuitive interfaces and workflows atop diffusion-based video generation models like Sora, which will determine their usability and adoption;

-

Training Sora demands immense computational resources—we estimate approximately 4,200–10,500 Nvidia H100 GPUs running for one month;

-

During inference, each H100 can generate around 5 minutes of video per hour. The inference cost for diffusion-based models like Sora is orders of magnitude higher than that of LLMs;

-

As video generation models like Sora see broad deployment, inference will surpass training as the dominant consumer of computational resources. This tipping point occurs after generating 15.3 million to 38.1 million minutes of video, when cumulative inference compute exceeds initial training compute. By comparison, users upload 17 million minutes daily to TikTok and 43 million to YouTube;

-

Assuming AI-generated content reaches significant penetration—50% of TikTok videos and 15% of YouTube videos—we estimate peak inference demand would require approximately 720,000 Nvidia H100 GPUs, factoring in hardware efficiency and usage patterns.

Overall, Sora represents a major leap forward in video generation quality and functionality, while signaling a likely surge in GPU demand driven by inference workloads in the future.

01. Background

Sora is a diffusion model. Diffusion models are widely used in image generation—for example, OpenAI’s DALL·E or Stability AI’s Stable Diffusion. Similarly, emerging video generation startups like Runway, Genmo, and Pika are also likely leveraging diffusion architectures.

Broadly speaking, as generative models, diffusion models learn to reverse a process that gradually adds random noise to data, enabling them to generate outputs similar to their training data—such as images or videos. These models start from pure noise and progressively denoise and refine patterns until they produce coherent, detailed results.

Diagram illustrating the diffusion process:

Noise is gradually removed until detailed video content emerges

Source: Sora Technical Report

This process differs fundamentally from how LLMs operate. LLMs generate tokens sequentially through autoregressive sampling. Once a token is generated, it remains fixed. When using tools like Perplexity or ChatGPT, you observe answers appearing word by word, as if someone were typing.

02. Sora’s Technical Details

Alongside Sora’s release, OpenAI published a technical report—but it offers very few specifics. However, Sora’s design appears heavily influenced by the paper "Scalable Diffusion Models with Transformers," where two authors introduced DiT, a Transformer-based architecture for image generation. Sora seems to extend this work into the video domain. Combining insights from Sora’s technical report and the DiT paper allows us to reconstruct much of Sora’s underlying logic.

Three important facts about Sora:

1. Sora does not operate directly in pixel space but instead performs diffusion in latent space (also known as latent diffusion);

2. Sora uses a Transformer architecture;

3. Sora appears to be trained on an exceptionally large dataset.

Detail 1: Latent Diffusion

To understand latent diffusion, consider how images are generated. One could apply diffusion to every individual pixel, but this would be highly inefficient—for instance, a 512x512 image contains over 260,000 pixels. Alternatively, pixels can first be compressed into a lower-dimensional latent representation, then diffusion is performed in this smaller latent space before decoding back to pixels. This drastically reduces computational complexity—from handling 260,000+ pixels down to just 64x64=4,096 latent elements. This approach was pioneered in High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models and forms the foundation of Stable Diffusion.

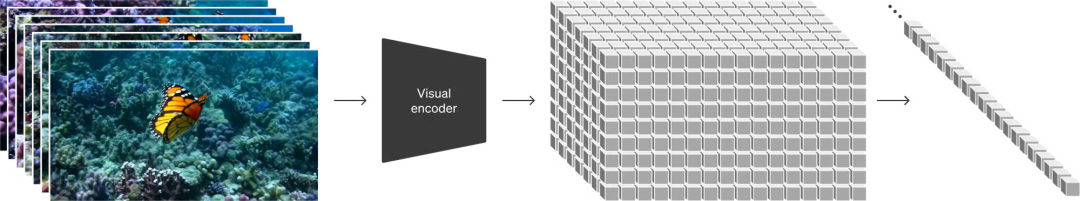

Mapping pixels from the left image to the grid-based latent representations on the right

Source: Sora Technical Report

Both DiT and Sora use latent diffusion. For Sora, there’s an added temporal dimension: videos are sequences of frames over time. As shown in Sora’s technical report, encoding from pixel space to latent space happens both spatially—compressing frame width and height—and temporally—compressing across time.

Detail 2: Transformer Architecture

Regarding the second point, both DiT and Sora replace the commonly used U-Net architecture with a standard Transformer. This is critical because the authors of DiT found that using Transformers enables predictable scaling: increasing compute—via larger models, longer training, or both—consistently improves performance. Sora’s technical report echoes this idea in the context of video generation, including a clear visual illustration.

Model quality improves with increased training compute: base level, 4x, and 32x compute from left to right

This scalable behavior can be quantified via scaling laws—a highly valuable property. Prior to video generation, scaling laws have been studied extensively in LLMs and other autoregressive models across modalities. The ability to improve model performance through scaling has been a key driver behind the rapid advancement of LLMs. Given that image and video generation also exhibit scaling properties, we should expect scaling laws to apply similarly here.

Detail 3: Dataset

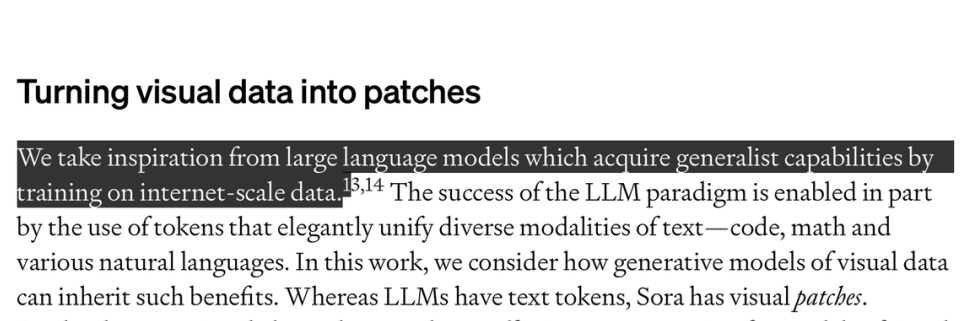

A final key factor in training a model like Sora is labeled data. We believe the dataset holds most of Sora’s secrets. To train a text-to-video model like Sora, we need paired data consisting of videos and corresponding textual descriptions. OpenAI did not elaborate much on the dataset but hinted it is massive. In the technical report, they wrote: “Inspired by the general capabilities acquired by LLMs trained on internet-scale data.”

Source: Sora Technical Report

OpenAI also described a method for annotating images with detailed text captions, used to build the DALL·E-3 dataset. Briefly, this involves training a captioning model on a labeled subset of data, then using that model to automatically label the rest. Sora’s dataset likely employs a similar technique.

03. Impacts of Sora

Video Models Entering Practical Use

In terms of detail and temporal coherence, Sora’s video quality marks a significant breakthrough. For example, Sora correctly handles occluded objects remaining stationary and accurately renders water reflections. We believe Sora’s current output quality is already sufficient for specific applications—for instance, potentially replacing certain stock video needs.

Landscape of video generation companies

However, challenges remain. It’s unclear how controllable Sora is. Since the model outputs pixels directly, editing generated videos is difficult and time-consuming. To make these models truly useful, intuitive UIs and workflows must be built around them. As shown above, Runway, Genmo, Pika, and others are already addressing these issues.

Scaling Accelerates Expectations for Video Generation

Earlier, we discussed how the DiT paper demonstrated that model quality improves directly with increased compute—a phenomenon consistent with known scaling laws in LLMs. Therefore, we can expect video generation quality to rapidly improve as models are trained with greater resources. Sora strongly validates this trend, and we anticipate OpenAI and other companies will double down on investment in this direction.

Synthetic Data Generation and Data Augmentation

In fields like robotics and autonomous driving, data remains inherently scarce—there’s no equivalent of the “internet” filled with robots doing tasks or self-driving cars collecting real-world footage. Typically, progress relies on simulation training, large-scale real-world data collection, or a combination. Yet both approaches face hurdles: simulated data often lacks realism, while real-world data collection is expensive and insufficient for rare events.

As shown, modifying video attributes enables augmentation—rendering original video (left) into dense jungle environment (right)

Source: Sora Technical Report

We believe models like Sora can help address these problems. They may be used to generate 100% synthetic training data or perform data augmentation by transforming existing videos in diverse ways.

This form of data augmentation is already illustrated in the technical report. An original video shows a red car driving along a forest road. After processing by Sora, the same car appears to drive through a tropical jungle. With the same technology, we could plausibly alter day/night cycles or weather conditions.

Simulation and World Models

“World models” represent a promising research direction. If accurate enough, such models could allow direct training of AI agents within simulations or support planning and search functionalities.

Models like Sora implicitly learn basic representations of how the physical world operates—from vast amounts of video data. While this “emergent simulation” capability is still imperfect, it is exciting: it suggests we might train world models at scale using video data alone. Furthermore, Sora appears capable of simulating complex phenomena such as fluid dynamics, light reflection, and motion of fibers and hair. OpenAI even titled their technical report Video generation models as world simulators, clearly indicating they view this as one of the model’s most impactful aspects.

Recently, DeepMind demonstrated similar effects with its Genie model: trained solely on gameplay videos, the model learned to simulate games and even create new ones. Remarkably, it could adapt predictions or decisions based on unseen actions. In Genie’s case, the ultimate goal remains enabling learning within such simulated environments.

Video from Google DeepMind’s Genie:

Generative Interactive Environments introduction

Taken together, we believe models like Sora and Genie will play vital roles in large-scale training of embodied agents for real-world tasks. Of course, limitations exist: since these models are trained in pixel space, they simulate fine-grained details—even irrelevant movements like grass swaying in the wind. Although latent spaces compress information, they still retain much of this detail to ensure accurate reconstruction to pixels. Thus, it remains unclear whether effective planning can occur efficiently within latent space.

04. Compute Estimation

We are deeply interested in understanding the respective computational demands of training and inference, as this helps forecast future resource needs. However, due to minimal public information on Sora’s model size and dataset, any estimation comes with high uncertainty. The following figures should therefore be treated cautiously.

Inferring Sora’s Compute Scale Based on DiT

Detailed information about Sora is scarce. But revisiting the DiT paper provides a useful reference point, as it clearly underpins Sora’s design. The largest DiT model, DiT-XL, has 675 million parameters and required approximately 1,021 FLOPS of total compute during training. To contextualize, this equals about 0.4 Nvidia H100 GPUs running for one month—or one H100 running for 12 days.

Currently, DiT is used for image generation, whereas Sora generates videos. Sora can produce up to one-minute-long videos. Assuming a 24 fps encoding rate, that’s 1,440 frames. Sora compresses both spatial and temporal dimensions when mapping from pixels to latent space. If we assume the same 8x compression ratio as in the DiT paper, the latent space contains 180 frames. A simple linear extrapolation from DiT to video implies Sora requires 180 times more compute than DiT.

Additionally, we believe Sora’s parameter count far exceeds 675 million—potentially reaching 20 billion. This suggests another 30x multiplier in compute compared to DiT.

Finally, we believe Sora’s training dataset is vastly larger than DiT’s. DiT was trained with a batch size of 256 over 3 million steps—processing ~768 million images total. Note that due to ImageNet containing only 14 million images, this involved heavy data reuse. Sora appears trained on a mixed dataset of images and videos, though specifics are unknown. Let’s assume 50% static images and 50% videos, with the overall dataset 10–100x larger than DiT’s. However, since DiT reused data extensively, and given the availability of larger datasets, such repetition may be suboptimal. A more reasonable multiplier for dataset-driven compute increase is thus 4–10x.

Combining all factors and considering different assumptions about dataset scale yields the following estimates:

Formula: Base DiT compute × model size multiplier × dataset multiplier × 180-frame video multiplier (applied to 50% of data)

-

Conservative dataset estimate: 1,021 FLOPS × 30 × 4 × (180 / 2) ≈ 1.1×10²⁵ FLOPS

-

Optimistic dataset estimate: 1,021 FLOPS × 30 × 10 × (180 / 2) ≈ 2.7×10²⁵ FLOPS

Sora’s compute requirement corresponds to 4,211–10,528 Nvidia H100 GPUs running for one month.

Compute Demand: Inference vs Training

Another crucial aspect is comparing training and inference compute. Theoretically, training compute, however large, is a one-time cost. In contrast, although inference requires less compute per run, it accumulates with every generation and scales with user growth. As adoption increases, inference becomes increasingly significant.

Thus, identifying the inflection point where cumulative inference compute surpasses training compute is valuable.

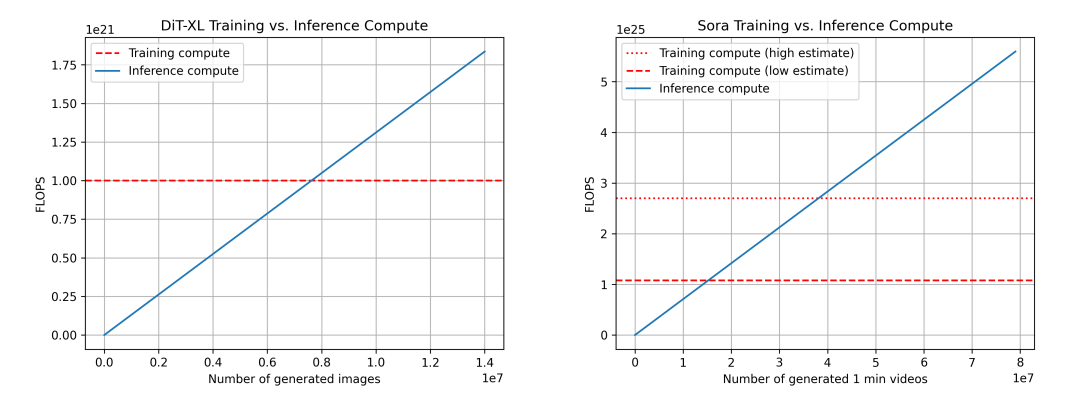

We compare training-inference compute ratios for DiT (left) and Sora (right). For Sora, our estimates are uncertain. Two training compute scenarios are shown: low (dataset multiplier = 4x) and high (multiplier = 10x).

Using DiT as a proxy again: DiT-XL performs 524×10⁹ FLOPS per inference step. Generating one image takes 250 diffusion steps—totaling 131×10¹² FLOPS. After generating 7.6 million images, cumulative inference compute matches training compute—the “inference-training crossover.” For reference, Instagram sees ~95 million image uploads daily.

For Sora, we estimate: 524×10⁹ FLOPS × 30 × 180 ≈ 2.8×10¹⁵ FLOPS per step. With 250 diffusion steps, total FLOPS per video ≈ 708×10¹⁵ FLOPS. This equates to roughly 5 minutes of video per hour per H100. Under conservative dataset assumptions, the inference-training crossover occurs after generating 15.3 million minutes of video; under optimistic assumptions, after 38.1 million minutes. For reference, ~43 million minutes of video are uploaded to YouTube daily.

Additional considerations: FLOPS aren’t the only factor during inference. Memory bandwidth matters too. Active research aims to reduce diffusion steps, lowering compute needs and accelerating inference. FLOPS utilization may also differ between training and inference phases.

Yang Song, Prafulla Dhariwal, Mark Chen, and Ilya Sutskever published Consistency Models in March 2023, noting that while diffusion models achieved major advances in image, audio, and video generation, they suffer from iterative sampling and slow generation. Their proposed consistency models enable fewer sampling steps while maintaining quality. https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.01469

Inference Compute Requirements Across Modalities

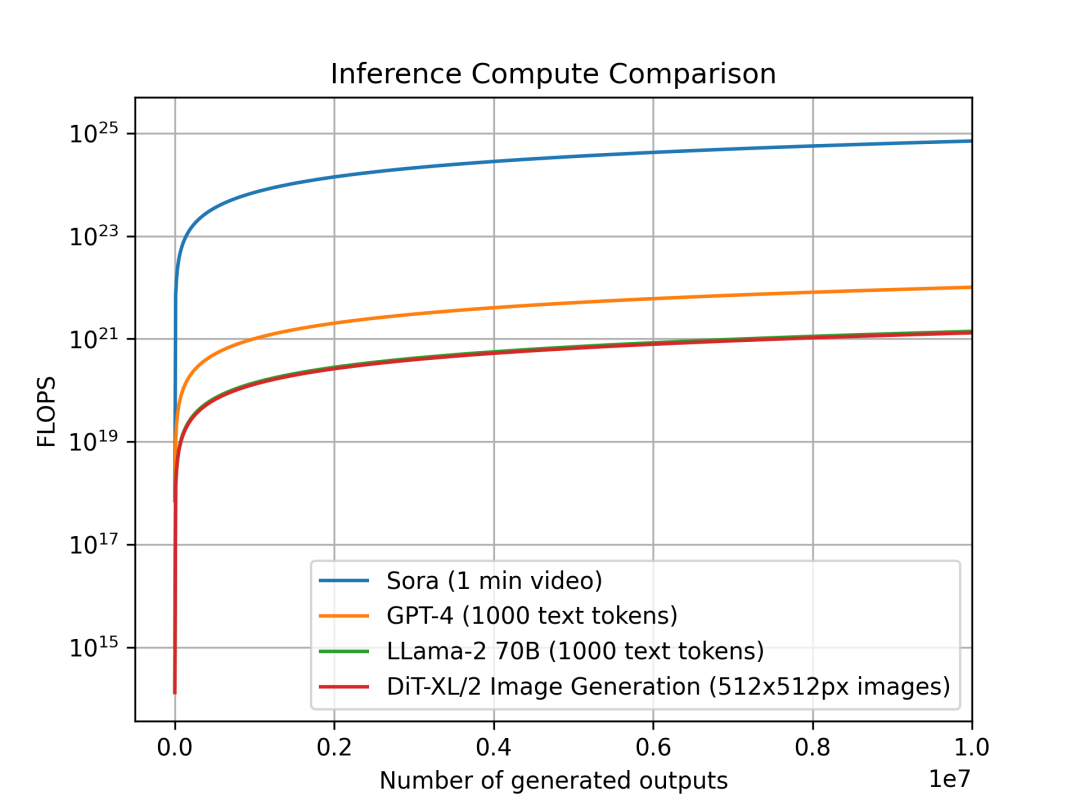

We analyzed inference compute trends per unit of output across different modalities. This helps assess how computationally intensive inference becomes across model types—critical for infrastructure planning. Outputs vary by modality: Sora generates one-minute videos; DiT produces 512x512 images; Llama 2 and GPT-4 output documents with 1,000 tokens (for reference, average Wikipedia articles contain ~670 tokens).

Comparison of inference compute per output unit: Sora (1-minute video), GPT-4 and Llama 2 (1,000-token text), DiT (512x512 image). Sora’s estimated inference compute is orders of magnitude higher.

We compared Sora, DiT-XL, Llama2-70B, and GPT-4, plotting their FLOPS on a log scale. For Sora and DiT, we used earlier inference estimates. For Llama 2 and GPT-4, we applied the heuristic “FLOPS = 2 × parameter count × generated tokens.” For GPT-4, we assumed a MoE architecture with 220-billion-parameter experts, activating two per forward pass. Note: GPT-4 specs are not officially confirmed and are illustrative only.

Source: X

We observe that diffusion-based models like DiT and Sora consume significantly more compute during inference: the 675-million-parameter DiT-XL consumes roughly the same inference compute as the 70-billion-parameter Llama 2. Even more strikingly, Sora’s inference cost exceeds GPT-4 by multiple orders of magnitude.

Again, many values used here are rough estimates based on simplified assumptions. They do not account for real-world GPU FLOPS utilization rates, memory capacity and bandwidth constraints, or advanced techniques like speculative decoding.

Projected inference compute demand if Sora-level video generation sees widespread adoption:

• As above, assume each H100 generates 5 minutes of video per hour—120 minutes per day.

• TikTok: 17 million minutes uploaded daily (34 million videos × avg. 30 sec), assume 50% AI-generated;

• YouTube: 43 million minutes uploaded daily, assume 15% AI-generated (mostly sub-2-minute videos);

• Total daily AI-generated video: 8.5M + 6.5M = 15 million minutes.

• Total H100s needed for TikTok and YouTube creator communities: 15M / 120 ≈ 89,000.

But 89,000 may be too low due to several factors:

• Assumes 100% FLOPS utilization, ignoring memory and communication bottlenecks. Realistic utilization is closer to 50%, doubling GPU needs;

• Inference demand isn’t uniform—it spikes. Peak traffic requires extra GPUs for reliability. Applying a 2x multiplier accounts for this;

• Creators often generate multiple versions before selecting one to upload. Assuming 2 generations per final upload doubles GPU demand again;

In total, peak demand could require approximately 720,000 H100s to meet inference needs.

This reinforces our belief that as generative AI becomes more popular and widely relied upon, inference compute will dominate demand—especially for diffusion-based models like Sora.

It’s also important to note that further model scaling will dramatically amplify inference compute needs. On the other hand, optimizations in inference techniques and broader tech stack improvements can partially offset this growth.

Video content creation directly drives demand for models like Sora

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News