The fallen mastermind behind a 10-billion-yuan illegal empire can't forget his first fortune earned from a private server of "Legend"

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

The fallen mastermind behind a 10-billion-yuan illegal empire can't forget his first fortune earned from a private server of "Legend"

Behind the bustling buildings of Phnom Penh, Cambodia, lies a massive gray and black industry network.

On January 7, Cambodia's Ministry of Interior issued a brief announcement on its official website: at China's request, three Chinese nationals—Chen Zhi, Xu Jiliang, and Shao Jihui—were arrested and extradited back to China. A month earlier, the Cambodian king had already issued a decree revoking Chen Zhi’s Cambodian citizenship.

In recent days, "Chen Zhi" and his "太子集团 (Taizi Group)" have likely appeared multiple times across your social media feeds. Across various reports, they are often described similarly: behind the bustling skyline of Phnom Penh, Cambodia, lies a massive gray-and-black industrial network of staggering scale.

On the surface, Taizi Group maintains good relations with local authorities and claims to operate over 100 commercial entities in more than 30 countries, spanning industries such as real estate, banking, aviation, and supermarkets.

Beneath the facade, however, Taizi Group is involved in money laundering, telecom fraud, online gambling, and operates a vast criminal empire worldwide.

A more dramatic footnote comes from the other side of the Pacific. In October 2025, the U.S. Department of Justice publicly filed documents seeking the seizure of 127,271 bitcoins under Chen Zhi’s name—worth approximately $15 billion at market value, setting a record for the largest asset forfeiture in U.S. judicial history.

Yet this represents only a fraction of Chen Zhi’s wealth. According to public records, one of his accomplices stated in 2018 that through “pig-butchering” scams and related criminal activities, Taizi Group earned over $30 million per day. Much of this immense income was used by Chen Zhi to purchase yachts, private jets, luxury mansions, and rare artworks including paintings by Picasso.

As the founder of this black-market empire, Chen Zhi’s origins seem rather ordinary. Born in 1987 in a fishing village in Fujian Province, he held only a high school diploma and once worked as an internet cafe administrator in Guangdong and Jiangsu provinces. He later engaged in data trading and operated gaming and social networking websites, claiming to have run an internet cafe.

How did a boy from a coastal village rise within just over a decade to become the central figure of a transnational crime network? When tracing his ascent, nearly all clues point unmistakably to one game widely known among Chinese players:

Legend.

The Escaped Knight

In 2018, Amiga Entertainment, a company under Chen Zhi, applied to open an account at the Cayman National Bank. According to leaked bank records, when questioned about the source of initial capital during compliance review, the young tycoon explained:

He received a personal loan of $2 million from an uncle, which he used to establish Hengxin Real Estate Company in Cambodia.

When the bank requested further details about the uncle’s assets, no additional information surfaced in the leaked documents. Compared to this mysterious relative, a more widespread account suggests Chen Zhi’s startup capital came from the then-popular game Legend.

In 2001, the South Korean online game Legend entered the Chinese market, quickly becoming a landmark product in the early days of China’s internet development. Just one year later, however, the server-side source code for the Italian version of Legend was accidentally leaked. With official licensing unable to meet massive player demand, numerous unauthorized “private servers” began appearing online.

Industry insiders estimate that at its peak, nearly a thousand Legend private servers operated simultaneously across China. The annual output value of the private server market exceeded 2 billion RMB, and including associated sectors like servers and payment settlements, the total industry scale surpassed 4 billion RMB.

During the era of rampant private servers, the key competitive advantage was “traffic.” Server operators needed to advertise their launch on dedicated platforms to attract players. With both large numbers of server operators and advertising sites, a lucrative intermediary business emerged between them.

Driven by enormous profits and operating within a vast, unregulated traffic distribution chain, several criminal organizations soon evolved—posing as ad agencies but actually conducting cyberattacks.

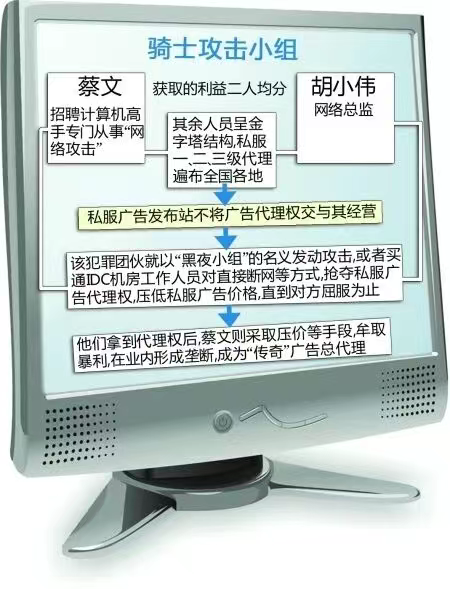

According to Caixin, multiple hackers and private server operators confirmed that Chen Zhi was once part of a group known as the “Knight Attack Team.”

The “Knight Attack Team” was notorious in the Legend private server community. Its founder Cai Wen started out in private server ad brokerage. To monopolize agency rights and lower prices, the group used DDoS attacks to systematically disable competing ad platforms that refused cooperation.

Under continuous cyberattacks, 13 of China’s largest private server listing websites—including SF123—were forced into submission, handing over their advertising rights entirely to the Knight Attack Team.

By the end of 2008, after earning 10 million RMB from monopolizing ad rights, Cai Wen was investigated by police in Xiantao, Hubei for suspected illegal business operations. However, after paying a 5 million RMB “bail,” he fled to Chongqing to reunite with his friend Hu Xiaowei, planning a comeback.

In Chongqing, the Knight Attack Team upgraded its tactics. When technical attacks failed, they bribed hosting providers of rival ad platforms to physically disconnect servers, causing targeted websites to go offline.

Image source: Chongqing Business Daily

Using these violent methods, the Knight Attack Team became increasingly dominant. By the time the case broke in 2011, the group had amassed nearly 100 million RMB in profits and built four of its own ad platforms. Despite being investigated twice by police, they each time avoided punishment by surrendering 10 million RMB as “deposit.”

In 2011, under a directive from China’s Ministry of Public Security, Chongqing police officially cracked this illegal computer intrusion case. Nineteen suspects were arrested, while a main perpetrator, “Hu Xiaowei,” fled abroad. Notably, Chen Zhi was not among those captured.

The same year, Chen Zhi, already overseas in Southeast Asia and carrying mysterious startup funds, began entering Cambodia’s real estate sector.

The two men who quietly escaped the storm did not go their separate ways. Instead, they formed even closer collaboration abroad, transferring the dark-gene默契 forged in criminal networks into broader international waters.

Hu Xiaowei, born in 1982, five years older than Chen Zhi, has been referred to by Chen as his “elder brother” on multiple occasions. According to a report by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), this “elder brother” used the alias “Chen Xiaoe” overseas and obtained a passport from the Federation of Saint Kitts and Nevis in 2018.

Later, in the Pacific island nation of Palau, Chen Zhi co-founded Grand Legend International Asset Management Group with “Chen Xiaoe,” the passport holder.

Although primarily focused on developing luxury resorts, the company’s name clearly reflects the founders’ nostalgic sentiment toward “Shanda Legend.”

As Taizi Group expanded, Hu Xiaowei began frequently appearing under aliases such as “Chen Xiaoe” and “Hu Shi” in equity changes and overseas entity lists linked to the group.

In Singapore and Cyprus, shares of multiple Taizi-affiliated entities were repeatedly transferred between Chen Zhi and Hu Xiaowei over several years. In Taiwan, Hu Xiaowei was described by local media as the second-in-command of Taizi Group, assisting Chen in managing financial operations of Taiwanese subsidiaries, with substantial funds flowing weekly into accounts he controlled.

According to a former executive overseeing Taizi Group’s operations in Taiwan, Chen Zhi repeatedly stated that Hu Xiaowei was “the one who introduced him to online gaming,” highlighting their close relationship.

And Chen Zhi never let go of this path paved by Legend.

Legend Casino

In 2020, a criminal judgment released by the Luojiang District People’s Court in Deyang, Sichuan revealed how Chen Zhi’s Taizi Group leveraged Legend private servers to run gambling operations.

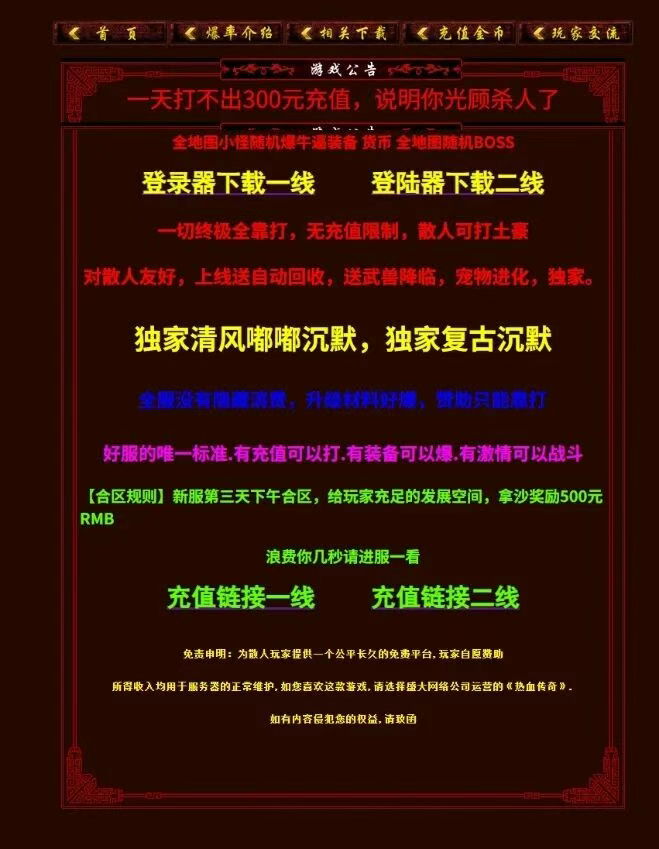

The verdict states that in early 2019, a company named “73 Network,” based in Taizi Building, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, began setting up Legend private server websites and operated multiple servers including “Cangjiang Heji,” “Qilin Heji,” and “Guangyao Huolong.”

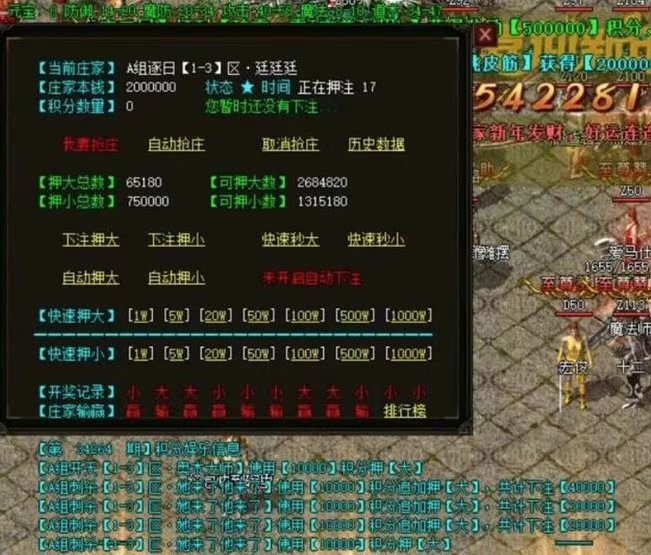

Unlike traditional game operations, these servers did not profit from game cards or virtual items. Instead, they embedded a gambling plugin called “Pang Niu” directly into the game interface. The gambling rules were extremely simple—each round settled every 45 seconds, running 24 hours a day, with single-round wins or losses reaching tens of thousands of RMB.

Technical staff admitted that several companies under Taizi Group in Phnom Penh specialized in operating private servers with the embedded “Pang Niu” software for gambling purposes, with “73 Network” being one of them. Each company had its own boss, but all belonged to the same alliance—ultimately part of Taizi Group.

To lure players into gambling, these servers implemented an “entertainment value” threshold system. In servers like “Qilin Heji,” high-level maps offered far better drop rates than regular ones, but access required sufficient “entertainment value.” Similarly, dropped equipment could be cashed out for RMB—but again, only if the player had enough entertainment value.

Some products listed in the verdict still accessible via certain channels today

Regardless of win or loss, players earned entertainment value simply by placing bets within the “Pang Niu” plugin. This mechanism forced most players—especially those chasing high-end gear or hoping to profit from drops—to gamble, completing the transformation from gamer to gambler.

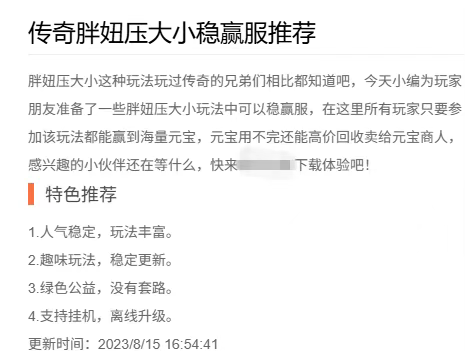

Some private servers explicitly named themselves “Pang Niu Big-Small Always Win Server”

For fund settlement, these servers established an agent system called “Shanghang” (merchant banks). Players paid WeChat, Alipay, or bank transfers to Shanghang to buy in-game currency (yuanbao), while Shanghang profited from exchange spreads and a 5% in-game “service fee.”

An audit report showed that “73 Network” alone used 137 bank cards and 26 Alipay accounts for financial transactions. Between 2015 and 2020, the total inflow and outflow of funds through this criminal network reached 4.515 billion RMB. Additionally, the operation extended to mobile apps, enabling data synchronization between web and mobile platforms, further expanding its revenue reach.

Searching Chinese court documents using keywords like “Legend” and “Pang Niu” reveals a continuous stream of casino-style businesses disguised as private servers. Yet, Taizi Group’s ambitions seemed to extend even further.

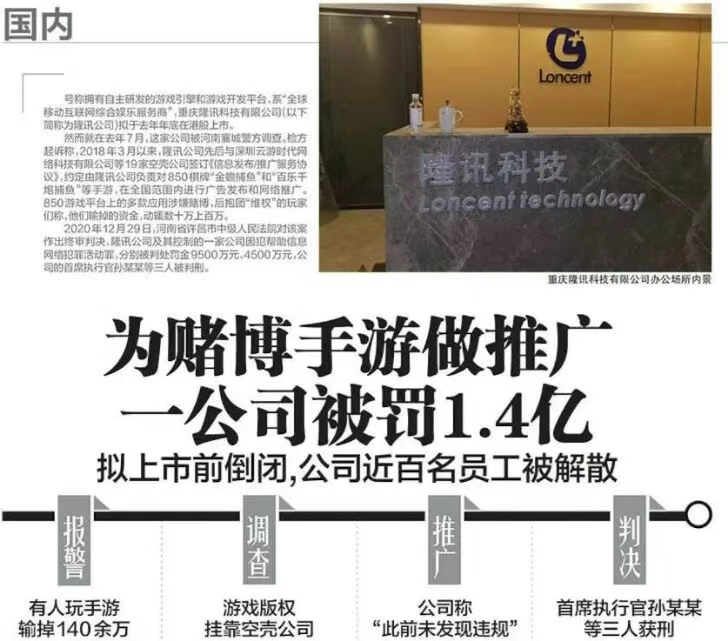

Wei Qianjiang, a core associate of Chen Zhi and former independent non-executive director of Hong Kong-listed Zhihaoda Holdings, began establishing operations in Beijing, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong starting in 2017. Central to this effort was Chongqing Longxun Technology Co., Ltd. (hereinafter “Longxun Tech”), a mobile internet enterprise based in Chongqing.

Longxun Tech presented itself as a comprehensive interactive entertainment company focused on global mobile game publishing, distribution, and development, claiming proprietary game engines and platforms. It reportedly raised $50 million in Series A funding in 2017.

According to the Chongqing Evening News, Longxun Tech sold the overseas distribution rights for one of its 3D mobile games in Singapore for 20 million RMB. In 2018, the company achieved total revenue exceeding 250 million RMB.

TapTap still shows the interface of its product “Super God Awakening,” still fond of the word “Legend”

Under Wei Qianjiang’s leadership, Longxun Tech planned to go public on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange by the end of 2020, aiming to become the fourth Hong Kong-listed company under Chen Zhi’s control.

However, in July 2020, a raid by Xiangcheng County police in Henan abruptly ended its IPO plans. Investigations revealed that Longxun Tech’s profits did not come from legitimate game distribution, but from signing fake “Information Publishing/Promotion Service Agreements” with 19 shell companies to provide full-scale advertising and online promotion services for highly gambling-oriented mobile games such as “Golden Toad Fishing” and “Hundred Le Thousand Cannon Fishing” developed by 850 Chess & Cards.

One player reported unknowingly losing over 1.4 million RMB: “I transferred money to designated bank accounts, and middlemen bought and sold points for me, but I almost never won—until I lost all the money I could afford.”

The verdict indicated that Longxun Tech illegally transferred and laundered funds through multiple shell companies, involving a total of 430 million RMB. In December 2020, the Intermediate People’s Court of Xuchang City, Henan Province, ruled in the first instance that Longxun Tech and affiliated companies were guilty of “aiding and abetting cybercrime activities,” imposing fines of 95 million and 45 million RMB respectively. The CEO and several executives were sentenced to prison, while Wei Qianjiang fled. As a result, Longxun Tech, once valued at hundreds of millions of dollars, collapsed rapidly.

Meanwhile, “Chongqing Quzu Infinite Equity Investment Fund,” founded around the same time as Longxun Tech, claimed to be a high-tech venture capital fund investing in internet, mobile internet, and mobile gaming industries. Wei Qianjiang remains a “founder” holding 30% shares, while Chen Zhi holds the remaining 70%.

Beneath the capital shells of these “gaming companies,” what was constantly refined was never the product—but rather, how to hunt human nature more efficiently.

The Game of Human Nature

In a 2007 interview, Chen Tianqiao, former richest man in China and founder of Shanda Interactive Entertainment, said: “Games truly strike straight into the heart. From a dialectical perspective, the more varied the form, the deeper it hits the soul. Conversely, the more you want to touch the soul, the less you should be bound by form. The same applies to business models—we can abandon anything, but we must never give up our grasp of human nature.”

The success of Legend today also stems from developers’ precise understanding of human nature. In 2001, Shanda acquired the mainland rights to 热血传奇 (The Legend of Mir) for $300,000. Facing overwhelming popularity and frequent shortages of physical game cards, they developed an online sales system “E-sales” and partnered with internet cafes for card distribution.

Profit-sharing turned internet cafe owners into stakeholders. Driven by profit motives, cafes nationwide spontaneously promoted the game, helping The Legend of Mir become the first Chinese online game to surpass 500,000 concurrent players—a milestone in Chinese gaming history. Riding this wave, Shanda went public on NASDAQ in 2004.

From a gameplay standpoint, Legend indeed strikes deep into human psychology. Because weak monsters could randomly drop top-tier gear, combined with open PvP and loot-dropping mechanics, rewards were both unpredictable and extremely scarce—triggering strong dopamine responses in the brain. Terms like “Dragon-Slaying Blade” and “Paralysis Ring” have transcended the lifecycle of the gaming industry and remain embedded in players’ lexicons today.

For early gamers, Legend almost perfectly placed “gain” and “loss” side by side, creating a unique closed loop built on “greed and fear” through low learning barriers and high emotional returns—an experience difficult to replicate at the time.

But can we say the gameplay of Legend itself carries some “original sin”?

In that “wild west” era of weak copyright awareness and immature regulation and enforcement, the fame of any phenomenon-level product naturally attracted gray- and black-market exploitation.

The prevalence of Legend private servers arose precisely because they amplified these psychological triggers—faster leveling, higher drop rates, direct numeric trading—leveraging Legend’s brand recognition and user base. Every link in the private server chain essentially put human psychological thrills on a scale and traded them openly.

It wasn’t until figures like Chen Zhi emerged that more radical approaches followed—directly embedding illegal content such as online gambling into gameplay. Though still labeled “games,” Legend became merely a conduit—easier to spread, harder to detect—for illicit traffic diversion.

To most modern casual players, “Legend private servers” sound like relics of a past internet age, seemingly distant from daily life. But according to official enforcement data, they haven’t disappeared entirely.

According to Shengqu Games’ “2024 IP Protection Report,” the company reported 138 private server and cheat cases to police in one year, took down over 1,400 infringing online games, and shut down more than 160 private servers.

Ongoing crackdowns have compressed gray-market space to some extent, yet they also reveal that IP infringement and derivative black-market activities around gaming remain a persistent challenge requiring long-term governance. Beneath the surface, we still don’t know how many products exist that use games as a front for illegal activities.

Conclusion

Since its birth, Legend has been a game that deeply exploits human nature. Yet in news surrounding Chen Zhi, it becomes more like a parable of clear-cut morality.

Chen Tianqiao, another figure who accumulated wealth during the Legend era, gradually stepped away from China’s gaming industry. After resigning as chairman of Shanda Games and disposing of related equities, he directed much of his personal fortune toward scientific research:

In 2016, Chen Tianqiao announced the establishment of the Tianqiao and Chrissy Chen Institute (TCCI), supporting fundamental research in neuroscience and contributing to the development of domestic research platforms. Publicly, he often links this path to his personal health journey—stepping back from the extreme pressures of entrepreneurship, he now views “understanding the brain” as a longer-term mission.

Neuroscience research institutes founded by Chen Tianqiao in China and the United States

For criminals, however, wealth accumulation seems endless. After earning his first fortune from private servers, Chen Zhi quickly redirected his understanding of rules, human nature, and traffic toward more隐蔽, profitable, and destructive cross-border criminal networks.

As the “industry” grew larger, various actors gathered, specialized, and iterated around it, creating black-market practices parasitic on this massive ecosystem. There would always be a new set of “game rules” to prey upon others driven by the same greed.

Do rules inevitably lead to evil? Probably not. The same game, seen through the eyes of a developer, is merely a product and a business. But for those who see games as hunting grounds, it becomes a convenient net—they do catch what they seek, but ultimately face not another payout, but legal reckoning and accountability.

Paths diverge between humans and demons; in the end, no “game rules” can save them.

Footage from CCTV: Chen Zhi, ringleader of a major cross-border gambling and fraud syndicate, escorted back to China from Cambodia

References:

“Taizi Group Founder Chen Zhi Extradited Back to China: Inside the Rise of His Billion-Dollar Black Empire,” Caixin, 2026

“Investigation into Taizi Group’s Chen Zhi,” Hong Kong 01, 2025

“Company Fined 140 Million for Promoting Gambling Mobile Games,” Chengdu Business Daily, 2021

“Hackers Form Online ‘Mafia’ and Arrested for Profiting 70 Million,” Chongqing Business Daily, 2011

“The Hidden World of Hackers and Private Game Servers,” Chu Yunfan, 2013

“First Instance Criminal Judgment in Case of Opening Casinos by Jin et al.,” Luojiang District People’s Court, Deyang City (2020) Chuan 0626 Xing Chu No. 70

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News