From the "140k Poverty Line" to the "Middle-Class Slaying Line": To Live or to Live with Dignity?

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

From the "140k Poverty Line" to the "Middle-Class Slaying Line": To Live or to Live with Dignity?

It's not that the American people have actually become poorer, but rather their money is increasingly unable to stretch when faced with those "inefficient yet exorbitantly priced" services.

The narrative of the "kill zone" is something I first noticed in the X and Substack circles back in November. It originated from Mike Green's theory of the "$140k poverty line" going viral in the U.S. I didn't expect that over a month later, this narrative would spread to China and mutate into the "kill zone"—quite fascinating.

Unfortunately, my AI narrative radar (see here) wasn't ready yet—otherwise, I would've loved to see whether AI could catch the spread and evolution of this narrative.

01

At the end of November, I read three articles by Mike Green on Substack:

These are three extremely long articles—so long they feel like reading forever. Together, they amount to nearly a small book.

I’ll try to summarize them in plain language:

The gist is: if you think current economic data looks good, but still find life tight—even earning $100k a year yet feeling poor—it’s not your fault. The ruler measuring wealth and poverty is Doraemon’s self-deceiving tape measure.

The article presents three key points:

1. The “poverty line” is outdated

The official U.S. poverty line for a family of four is an annual income of $31,200; as long as your income exceeds $30k, you’re not considered poor.

But this benchmark was set in 1963. Back then, the logic was simple: a household spends about one-third of its income on food, so just calculate the minimum cost of food and multiply it by three—that’s the poverty line.

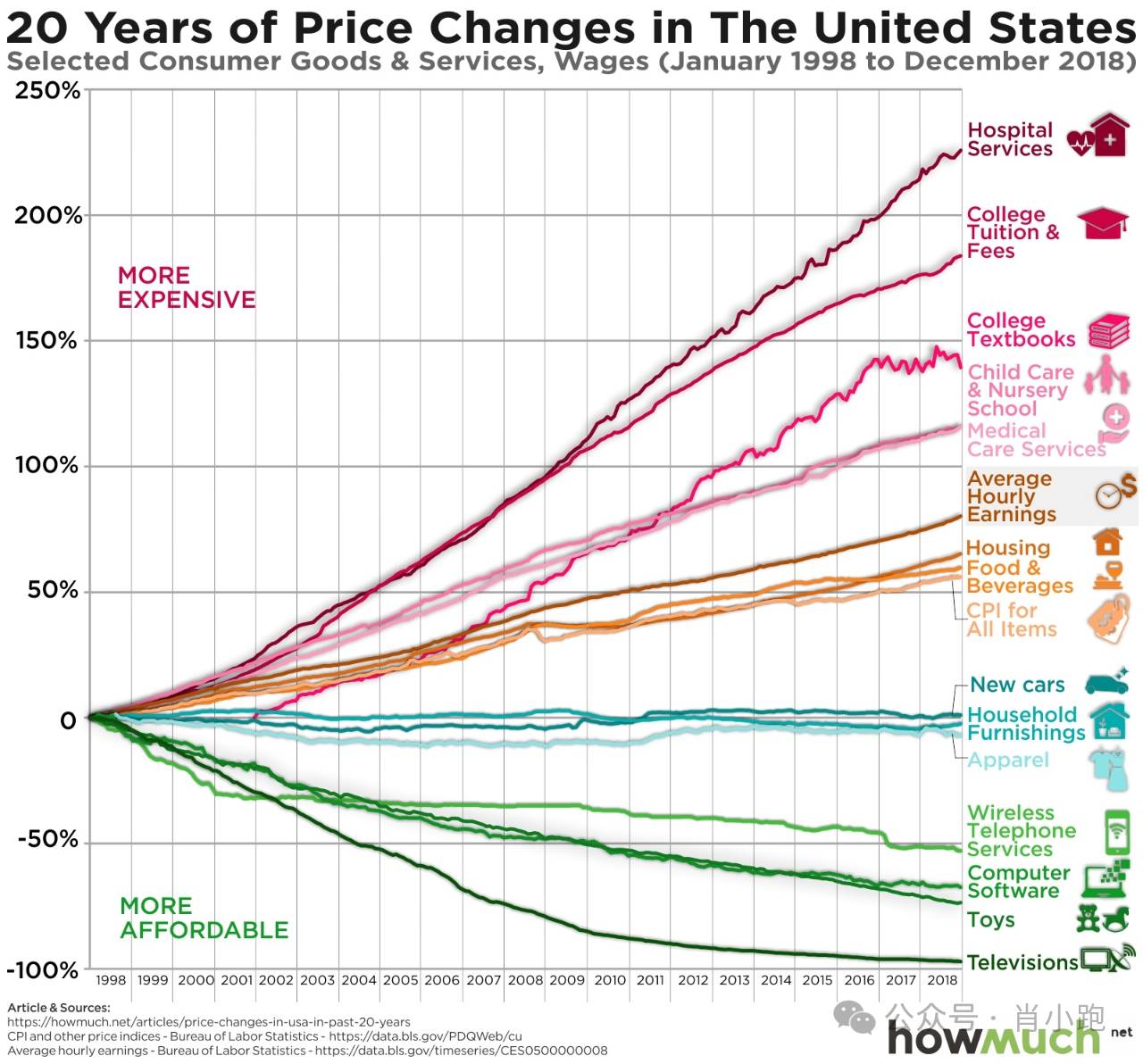

Now, things have changed dramatically. You’ve probably seen the famous chart illustrating “Baumol’s Cost Disease”:

Food has become cheaper, but housing, healthcare, and childcare costs have skyrocketed. If you recalculate the real poverty line based on 1963 standards—meaning being able to “participate” normally in society (having a home, a car, childcare, access to medical care)—the true threshold isn’t $30k, but $140,000 (about 1 million RMB), just enough to live decently today.

2. The harder you work, the poorer you get

The U.S. welfare system has a major flaw: when you earn $40k annually, you’re officially poor and qualify for food stamps, Medicaid, and childcare subsidies. Life is tight, but there’s a safety net.

But when you work hard and raise your income to $60k, $80k, or even $100k, disaster strikes: your income increases, but benefits disappear. Now you must pay full price for expensive health insurance and rent.

The result? A household earning $100k may end up with less disposable cash each month than a $40k-earning household receiving benefits.

This is where the Chinese internet narrative of the “kill zone” and “the kill zone targets the middle class” comes from: like in video games, when health drops below a certain threshold, a skill instantly kills you. The squeezed middle class hits the exact point where benefits phase out, taxes rise, and rigid expenses (healthcare, rent, childcare, student loans) pile on—all while losing subsidies and bearing high costs. Once hit by unemployment, illness, or rent hikes, they’re locked into the kill zone.

3. Your assets are mostly illusory

Because:

Your house isn’t an asset—it’s prepaid rent: if your home value rises from $200k to $800k, are you richer? No. Because if you sell it, you’d still need to spend $800k to buy a similar home. You gain no extra purchasing power—your cost of living simply increased.

Your expected inheritance isn’t wealth transfer: Baby Boomers’ inheritances won’t go to you—they’ll go to nursing homes and the medical system. In the U.S., long-term care (dementia care, nursing homes) now costs $6,000–$10,000+ per month. An $800k family home will likely be converted into stacks of medical bills collected by hospitals and insurers.

Your class has become a caste: previously, hard work could lift you up. Now, it’s all about “entry tickets”—Ivy League degrees, insider recommendation letters—these “assets” inflate faster than housing prices. So earning $150k keeps you alive, but can’t buy your child a ticket into the upper class.

02

What exactly caused America’s “poverty line inflation” (or in our context, the “kill zone shift”)?

Mike Green identifies three turning points in American history:

Turning point 1: Union decline and monopolization in the 1960s led to lower efficiency and higher costs.

Turning point 2: The anti-trust reversal in the 1970s enabled massive corporate consolidation, market control, and suppressed wages.

Turning point 3 (you probably guessed it): The China shock. But the article argues it wasn’t China forcibly taking jobs—it was American capitalists engaging in capital arbitrage, moving nearly all factories overseas for profit.

But Professor Green doesn’t just critique—he offers a hardcore solution called the “Rule of 65,” essentially echoing the familiar Chinese idea of “land reform”: (1) Raise corporate taxes (but exempt investment); (2) Eliminate tax deductions for corporate borrowing, cracking down on financial speculation; (3) Relieve wage earners: drastically reduce payroll taxes (FICA) so ordinary people keep more cash. Where to make up the shortfall? Make the rich pay more—remove the cap on Social Security taxes for high earners.

Chinese experience is absolutely practical.

03

Professor Mike Green’s views went viral among the American middle class—but sparked collective backlash from elites and economists.

His articles do contain data flaws. For example, using data from affluent areas (Essex County, top 6% nationwide in housing prices) as national averages; assuming all children attend expensive daycare centers (costing over $30k annually), while most American families actually care for kids themselves; and some conceptual confusion, such as equating “average spending” with “minimum survival needs.”

Later, Green appeared on many podcasts to clarify: the $140k figure doesn’t refer to traditional “starvation-level” poverty, but rather the “decent living threshold” for an average family to live without government aid and still save a little.

While Green may have miscalculated the numbers, his critics haven’t won either—because regardless of the exact poverty line, people’s “feeling of poverty” is very real. And the “kill zone sensation” feels increasingly authentic—to both Americans and Chinese.

Why? I believe the real reason lies in “Baumol’s Disease.”

“Baumol’s Cost Disease” was proposed in 1965 by economist William Baumol to describe an economic phenomenon:

Certain industries (like manufacturing) improve efficiency through machines and technology, driving unit costs ever lower. But others (like education and healthcare) rely heavily on human labor, making it hard to significantly boost productivity—one class still takes one hour, one doctor still needs time per patient, unlike factories that can scale output exponentially.

Here’s the problem: overall wages rise along with high-efficiency sectors. To prevent teachers and doctors from quitting for higher-paying jobs, schools and hospitals must also raise salaries. Yet their productivity hasn’t improved—so costs soar, and prices follow.

In short: machine-driven sectors push up wages across the board; labor-dependent sectors must raise pay to retain workers, despite unchanged efficiency—therefore becoming more expensive. This is “Baumol’s Cost Disease.”

This explains why, in the earlier chart, lines representing industrial goods like TVs, phones, and toys trend downward (prices falling), while those for education, healthcare, and childcare spike upward.

The underlying logic is starkly realistic:

Any field replaceable by machines and automation sees ever-rising efficiency. Take smartphones: while prices haven’t dropped much, performance is light-years ahead of just a few years ago—computing power and storage have multiplied several times over. This is essentially a tech-driven “invisible price drop.” Not to mention Chinese manufacturing: solar panels, EVs, lithium batteries—with rising automation, costs have been driven to rock bottom.

The issue arises in areas where “machines can’t replace humans.” When I was young, one nanny could care for four kids. Today, she still handles at most four—or fewer, since modern parents demand more. Service sector productivity hasn’t improved in decades; in some cases, it’s regressed.

Yet in the U.S., to stop nannies and nurses from quitting for delivery gigs or factory jobs, service employers must raise wages to match broader income trends. The coffee you buy—the beans aren’t expensive, but the sky-high price mainly covers staff wages, rent, and utilities. Efficiency hasn’t risen, but wages must—so costs get passed onto consumers. (Note: this specifically refers to the U.S.)

Thus, the American middle-class families “slain” by the kill zone aren’t literally starving. They own cars, iPhones, and streaming subscriptions. But when faced with home-buying, medical care, or childcare—those “service-based expenses”—their wallets are instantly drained. So it’s not that Americans have truly become poorer, but that their money buys less and less when confronted with these “inefficient yet outrageously expensive” services.

At this point, I know what you’re thinking: Does China have a kill zone? Does it target the middle class? Has China’s poverty line also risen?

The answer is most likely no.

So perhaps China won’t see a “kill zone.” My discussion with President Liu on the podcast “Wall Talk” titled When China Becomes an Industrial Cthulhu, What Remains of Trade? Higher Productivity, Lower Wages? touched on this topic.

We Chinese understand China’s reality: Chinese society is far more sensitive to service pricing. People generally resist paying for non-productive tools—especially services. Within the structure of labor reproduction costs, certain service expenditures in China have long been suppressed—almost treated as “a wage that doesn’t need to be paid.” When services are undervalued and welfare stages differ, wage systems naturally take shapes entirely different from the West.

This creates a peculiar phenomenon: no matter what, you can somehow “survive”—because living costs can be compressed to extremely low levels.

So perhaps China doesn’t have a “kill zone,” but that doesn’t mean there’s no invisible threshold—such as: how low can service workers’ dignity go? How high can their workload climb?

So once again: everything has a cost.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News