A trade deficit does not make a country poorer

TechFlow Selected TechFlow Selected

A trade deficit does not make a country poorer

Trump's view on trade deficits is based on two fundamental misconceptions.

By Noah Smith

Translated by Block unicorn

I don't actually think you can defeat Trump's tariff policy by rationally debating or explaining economic theory. I mean, how do you argue with something like this?

I've accepted the idea that Americans will only broadly realize widespread tariffs are bad once they personally experience their negative consequences—that is, touch the proverbial hot stove. Fortunately, I think Americans might wake up quickly:

But regardless, this is an economics blog, so even though I don’t expect much political payoff from it, I should probably explain why trade deficits don’t make a country poorer (even if that doesn’t mean they’re fine).

Trump’s Misunderstanding of Trade Deficits

Trump and his advisors and followers believe trade deficits mean America is being “extorted” by foreigners. As I explained in yesterday’s post, this is why Trump sets tariffs at levels he believes will eliminate America’s trade deficit with each country.

Trump’s view of trade deficits rests on two fundamental misunderstandings. The first is a simple accounting error. His advisors look at the GDP formula and notice that imports are subtracted from GDP. What they don’t understand is that imports are also added into consumption and investment, so they must be subtracted at the end to remove them from the totals. The fact is, imports have no effect on GDP.

Trump’s second misunderstanding stems from the idea that imports would be replaced one-for-one by domestic production—that if you stop Americans from importing a washing machine, a U.S. company will just produce one more. That’s certainly one possible outcome, but not the only one. American consumers might simply go without a washing machine, making everyone poorer.

In fact, Trump and his team may not even realize these are two separate mistakes. They might think their mistaken belief about accounting (that imports reduce GDP) naturally follows from their mistaken belief about import replacement. These two errors reinforce each other.

In sum, because Trump misunderstands trade deficits in both ways, he thinks that when the U.S. runs a trade deficit with a country, that country is extorting us. He believes imports force America to reduce production, thereby lowering U.S. GDP—essentially stealing American output. Thus, he sees trade deficits as a measure of how much America has been stolen from.

But that’s simply not how trade deficits work.

Trade Deficits Are Like Buying on Credit

Suppose you import a washing machine from a Chinese person named Ruimin. Why would Ruimin give you that washing machine? There’s no such thing as a free lunch. You can basically pay for that washing machine in two ways. The first way is to give Ruimin something he wants—say, 50 interesting books (assuming Ruimin is known for loving books). The second way is to give Ruimin an IOU.

The first case is called balanced trade. You get a washing machine; Ruimin gets 50 books. No trade deficit or surplus.

The second case is unbalanced trade. Here, instead of giving Ruimin 50 books, you give him a U.S. Treasury bond. A bond is an IOU. In this case, you contribute to the U.S. trade deficit with China. A real good or service—the washing machine—moves from China to the U.S., while all that comes back is a piece of paper (or really, a number in a spreadsheet).

When you hear economists talk about trade, you might hear them mention the “current account” and the “capital account.” The current account is basically just the net flow of real goods and services, while the capital account is basically just the net flow of IOUs. If you give Ruimin an IOU in exchange for a washing machine, that means you’ve contributed to America’s current account deficit and its capital account surplus. Both simply mean “paying foreigners with IOUs.”

Now you can see why a trade deficit is like buying something on credit. When I buy a washing machine from Target using my credit card, I write an IOU and get a physical item in return.

Does buying a washing machine on credit mean Target extorted me? No. Does it make me poorer? No. I now have less money but more stuff. Likewise, a trade deficit means America has less money but more goods. It doesn’t mean America is poorer or being extorted by foreigners.

A Case Where Trade Deficits Can Be Beneficial

Asking whether trade deficits are good or bad is like asking whether buying things with borrowed money is good or bad. The answer is clearly, “It depends on whether what you bought was worth it.”

One important point to remember is that not all purchases are for consumption—many are actually productive investments. If a U.S. factory buys a $100,000 CNC machine from Japan, and the Japanese toolmaker simply deposits that money into U.S. Treasuries, this increases America’s trade deficit. But if the U.S. factory uses that machine to manufacture and sell $500,000 worth of auto parts, it profits—and so does America.

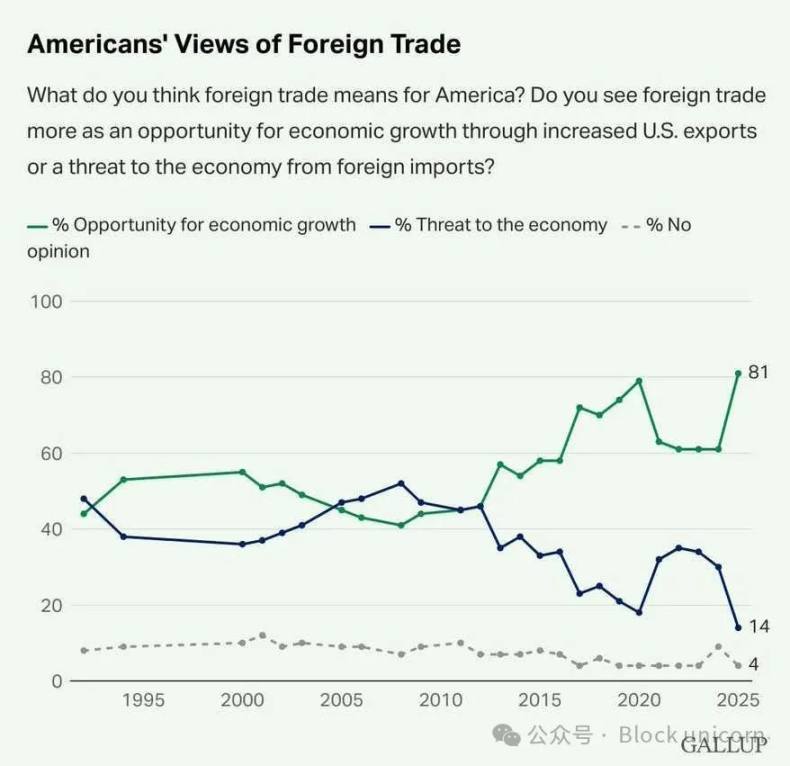

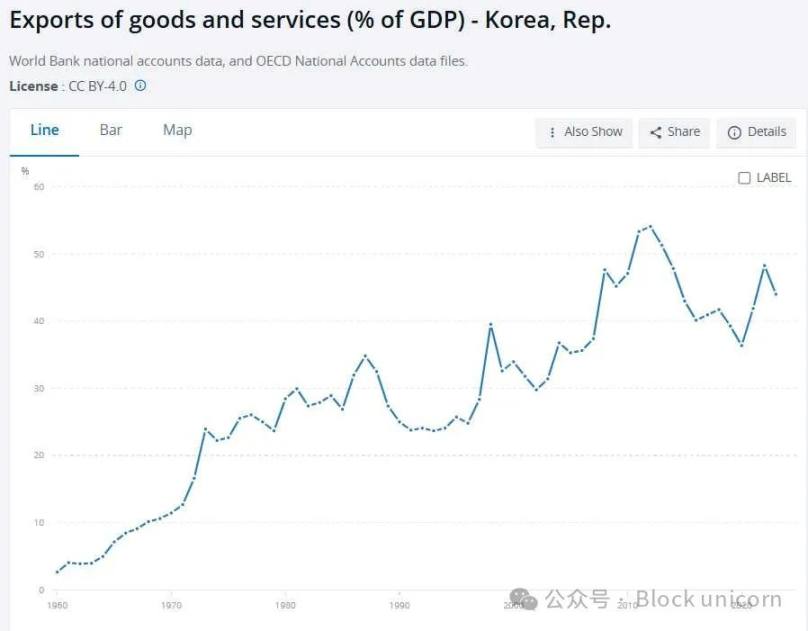

This is exactly what South Korea did during its rapid industrialization. Around 1980 and into the early 1990s, South Korea ran trade deficits:

During this period, South Korea was making massive investments in its industrial economy:

Incidentally, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, while running trade deficits, South Korea also increased exports—not just in dollar terms, but as a share of its GDP:

Remember, exports increase GDP, while imports don’t subtract from it. So even as South Korea ran large trade deficits, trade added increasingly more to its GDP every year. Something a MAGA supporter would find hard to grasp.

But anyway, South Korea’s trade deficits at the time were likely worthwhile because imported capital goods (machinery, etc.) helped them industrialize faster than if they had built all those machines themselves. They simply bought the machines and immediately used them to produce cars, TVs, and other useful things, most of which they sold profitably to the rest of the world.

In fact, America does some of this too. When we think of U.S. trade deficits, we usually think of consumer goods—cheap Chinese TVs and so on. But the U.S. also imports a substantial amount of capital goods, which American companies use to produce and sell products. America did this more in the 1990s, when we had trade deficits alongside a boom in investment and exports.

But caution: “using trade deficits for investment” doesn’t mean “trade deficits are good.” For example, if companies import lots of capital goods but earn low returns on investment, that could be bad.

What If Trade Deficits Fund Consumption? Is That Good or Bad?

So what happens when you use a trade deficit to buy consumer goods—those cheap Chinese TVs and Canadian-made cars? Today, consumer goods make up most of the U.S. trade deficit. Is this kind of trade deficit good or bad?

In this case, we have to decide whether “buy now, pay later” is good or bad. Remember, a trade deficit is like buying on credit. When America imports Chinese TVs and Canadian cars while China and Canada receive U.S. Treasuries, it means America now owes money to China and Canada.

At any time, China and Canada could choose to sell their bonds for dollars and then use those dollars to buy American goods and services. If they eventually do this, then at that point they’ll run a trade surplus with the U.S. Essentially, America borrowed from China and Canada and then paid them back.

It’s like using your credit card to buy a washing machine from Target, then working to earn wages and paying off the card. Is that bad or good? It depends. Maybe you could wait until you have cash in the bank to buy the washer. Or maybe for you, buying the washer now rather than waiting months is worth it, even if you have to pay a little interest on the debt.

Buying consumer goods with debt might be a good financial decision—or a bad one. That’s essentially what America is doing when it runs trade deficits with other countries.

It’s also worth noting, like a credit-card borrower, America might never fully repay its foreign loans. If the U.S. experiences unexpectedly high inflation, the value of U.S. bonds held by China and Canada will erode. That’s basically like a partial default. Or if one day a reckless U.S. leader defaults, China and Canada will see part of their bond holdings wiped out.

Thus, when America runs trade deficits with other countries, those countries are actually taking on risk. They’ve essentially given us a credit card we can use to buy things they make. But there’s always the chance we might declare bankruptcy and never pay up.

So in a sense, you could say the country running the trade deficit is more short-term oriented, or less patient, than the one running the surplus. Nations don’t have motivations and personalities like people do, but it’s not a terrible way to think about it.

Do Trade Deficits Cause Deindustrialization in America?

The final question here is whether importing things from other countries causes America to produce fewer things. Maybe if you buy tomatoes on credit, you end up planting fewer tomatoes in your own garden. Then when it’s time to repay the credit-card debt, you might have forgotten how to grow tomatoes. That’s basically what deindustrialization means.

Clearly, in some cases trade deficits don’t cause deindustrialization. In the case of South Korea in the 1980s and 1990s, for example, we saw trade deficits help the country industrialize and boost manufacturing. Something similar may have happened in the U.S. during the 1990s.

But okay, we’re not talking about historical cases, right? We’re talking about the past 25 years of U.S. trade deficits, primarily with China, but also many other countries. These deficits have mostly involved America borrowing to consume, not invest. The question is, have these deficits caused America to lose manufacturing capacity?

The answer, at least regarding China, is “definitely yes.” The famous study by Autor et al. (2013) found that “import competition from China explains one-fourth of the contemporaneous aggregate decline in U.S. manufacturing employment over 1990–2007.” Bloom et al. (2024) found that import competition from China led to large shifts of jobs from manufacturing to services on the West Coast and in big cities, while in the Midwest it mainly caused wage declines and unemployment. And Acemoglu et al. (2014) wrote:

In this paper, we investigate the impact of rising Chinese import competition on slow U.S. employment growth. We find that the rise in U.S. imports from China, accelerating after 2000, is a major cause of the recent U.S. employment losses in manufacturing and appears to have significantly suppressed overall U.S. employment growth through input-output linkages and other general equilibrium effects… Our central estimates indicate that rising Chinese import competition between 1999 and 2011 led to a net employment loss of 2.0 to 2.4 million jobs. [emphasis added]

You can roughly see this from the raw data. Until 2001, before China joined the WTO and began exporting vast quantities of cheap goods to the U.S., American manufacturing employment held up fairly well over the years (though its share of total employment was declining). In the 2000s—the decade of surging Chinese imports—it plummeted like falling off a cliff:

Notably, it wasn’t the trade deficit itself that caused these job losses. Even if U.S.-China trade had been balanced, Chinese import competition might still have cost some American manufacturing workers their jobs, because A) some U.S. exports might have been services rather than manufactured goods, and B) the U.S. might export more capital-intensive goods, no longer producing the labor-intensive products that China excelled at in the 2000s.

But indeed, the U.S. trade deficit with China was huge and contributed to a severe decline in industrialization. Persistent U.S. trade deficits with China may hinder American reindustrialization, both due to import competition and because China has crowded U.S. firms out of export markets.

Therefore, if you believe manufacturing matters beyond its contribution to GDP—as I do—then the trade deficit with China may be an important problem that needs addressing.

But that doesn’t mean Trump’s tariffs are the right solution! I know I’m repeating what I’ve written in many other posts, but it bears repeating. First, by raising the price of imported inputs, Trump’s tariffs are weakening U.S. manufacturers—that’s why auto workers and steelworkers are now being laid off, and why indicators of manufacturing activity and confidence are falling. Second, Trump’s tariffs will ultimately reduce U.S. exports as well as imports, both through exchange rate changes and retaliation by other countries. This harms U.S. manufacturing.

Tariffs on China could be part of a broader strategy to boost U.S. manufacturing competitiveness. But broad tariffs on all U.S. trading partners, like those Trump just rolled out, are likely to accelerate American deindustrialization—even if they also reduce the trade deficit. Ultimately, what matters for America isn’t reducing imports—it’s increasing exports. Trump’s tariffs only damage that goal.

Join TechFlow official community to stay tuned

Telegram:https://t.me/TechFlowDaily

X (Twitter):https://x.com/TechFlowPost

X (Twitter) EN:https://x.com/BlockFlow_News